- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1979 Topps Clarence Gaston

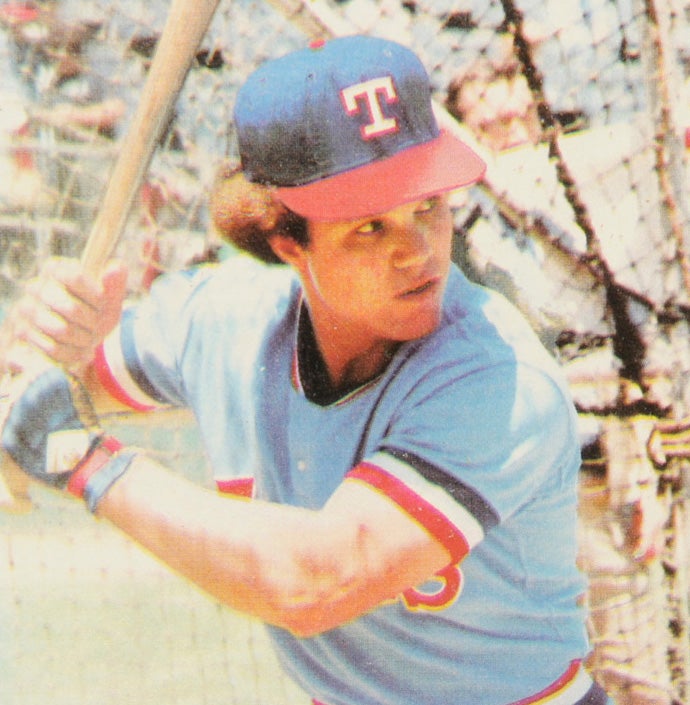

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Clarence Gaston

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Late in the 1978 season, the Pittsburgh Pirates purchased veteran Clarence “Cito” Gaston as part of an effort to win the National League East. He played in two games, accruing two at-bats and picking up one hit, as the Pirates finished second to the Philadelphia Phillies.

That late-season cameo left Topps scrambling. With no chance to photograph Gaston wearing the Pirates’ garish black-and-gold uniforms, but not wanting to exclude an established veteran like Gaston from its 1979 set, Topps moved into airbrush mode.

The airbrush artist had little trouble drawing the Pirates’ gold-colored jersey over the colors of Gaston’s old team, the Atlanta Braves. But the Pirates’ cap posed a problem. By now, the Pirates were using pillbox caps, which featured horizontal stripes and a flat top. Given the presence of the stripes and the unusual shape of the pillbox cap, it would have been very difficult for any artist to draw accurately over the existing Braves cap. So apparently someone at Topps gave the artist permission to simply airbrush a standard cap, one with a gold crown and a black bill, which the Pirates had not used since the 1975 season.

Unfortunately, any kind of a Pirates cap on Gaston would soon prove obsolete. That’s because the Pirates released Gaston over the winter. He re-signed with the Braves, receiving an invitation to attend Spring Training on a non-roster basis. But Gaston did not make the team. Instead, he spent the season in the Mexican League, before receiving another Spring Training invitation in 1980, this time from the Cleveland Indians. Once again, Gaston failed to make the Indians’ Opening Day roster, and once again, he spent the summer in Mexico. His 1978 cameo with the Pirates had represented his major league swansong.

There is another oddity to Gaston’s 1979 card. It lists him as “Clarence,” his given first name. But most baseball fans, particularly those who recall his days as the manager of the Toronto Blue Jays, remember Gaston as “Cito.” So what’s going on here? What did people actually call him, Clarence or Cito?

The answer is both. For the duration of his playing career, the media and fans referred to Gaston as Clarence. But as a child, growing up in the state of Texas, a boyhood friend had noticed a resemblance between Gaston and a famous Mexican wrestler named Cito. Some of Gaston’s friends began calling him Cito.

For some reason, the Cito nickname did not catch on in the big leagues until 1982, when the Jays hired him as their hitting coach. That’s when people in baseball started calling him Cito, with the name carrying over to his days as manager. (There was one exception to this; Blue Jays president Paul Beeston called him Clarence.)

To this day, people within the game refer to him as Cito. Clarence Gaston has become a ghost.

Long before the name change and his strangely airbrushed card, Gaston was a highly regarded outfield prospect who came up with the Milwaukee Braves’ organization. Long and lean, he stood 6-foot-3 and weighed 190 pounds, just the kind of body type that scouts seek in young players.

Al LaMacchia, a scout with the Braves, recalled seeing Gaston play in San Antonio for an amateur team sponsored by a welding company.

“Great build on him, wiry and strong. First thing he did was to chase a ball in deep center field, so I knew he could catch,” LaMacchia told George Vecsey of the New York Times. “Then he fired a strike so I knew he could throw. Then he beat out a groundball, so I knew he could run. And then he hit a home run, so I knew he had power.” Not surprisingly, LaMacchia signed Gaston.

He reported to Binghamton of the NY-Penn League in 1964, where he batted .238. He then moved up to Greeneville of the Western Carolinas League and struggled, hitting .230 in 49 games. In his second professional season, an assignment to the Florida State League resulted in a .188 batting average and no home runs in 202 at-bats. Based on his first two professional seasons, Gaston gave no indication of being a major league talent.

In 1966, the parent Braves (now relocated to Atlanta) farmed Gaston out to Batavia, an unaffiliated team in the NY-Penn League. Gaston blossomed with a new team, hitting .330 with 28 home runs and a .589 slugging percentage. He played so well that the Braves pushed him up to the Double-A Texas League in midsummer. For a player who had looked so overmatched during his first two seasons, it was a remarkable turn of events.

In 1967, Gaston continued to hit well in the Texas League, where he put up a .305 batting average while striking out 104 times in 136 games. In today’s game, few would have cared about the strikeouts, but at the time Gaston’s strikeout total did cause concern.

Still, the Braves called him up to Atlanta late in the summer. He came to bat 25 times for Atlanta, but collected only three hits.

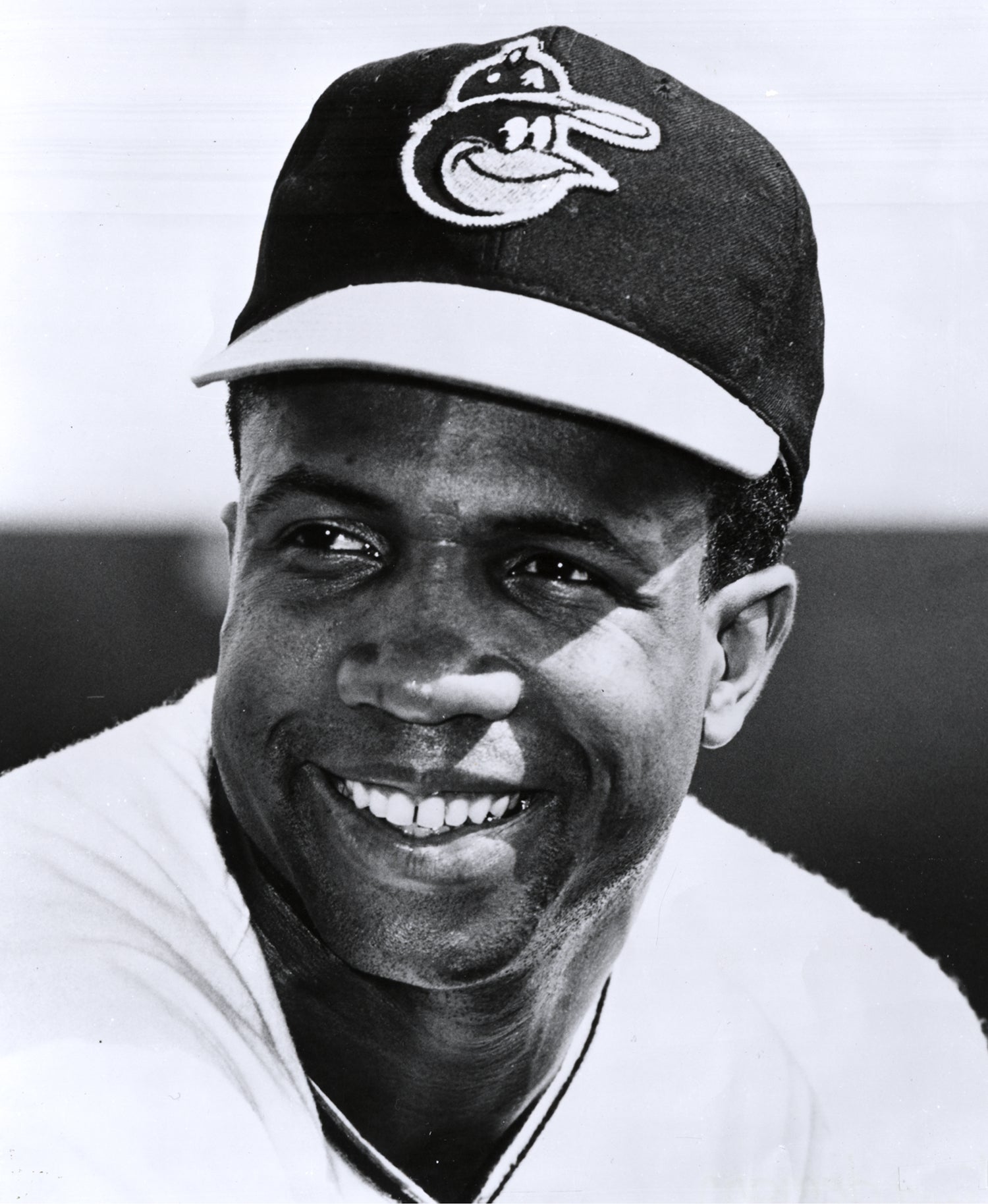

Though Gaston’s cup of coffee with the Braves lasted a handful of games, it paid a huge dividend for the young prospect. He had the good fortune of rooming with one of the Braves’ veterans, a 30-year-old outfielder named Hank Aaron. Gaston and Aaron became fast friends. Aaron helped guide the young Gaston, making him become more mature and responsible in his approach to the game.

That off-the-field experienced helped Gaston, even if he found major league pitching a bit challenging. Lacking in plate discipline, Gaston returned to the Texas League in 1968. He ended up splitting the season between Double-A and Triple-A, but his overall numbers were unimpressive. With an expansion draft coming up and with a deep outfield that featured Aaron, Felipe Alou and a comebacking Rico Carty (who had missed all of 1968 with tuberculosis), the Braves decided to leave the strikeout-prone Gaston unprotected.

They believed that the two new National League teams, the Montreal Expos and San Diego Padres, would be scared off by Gaston’s swing-and-miss tendencies.

Much to the Braves’ consternation, the Padres selected Gaston with their final pick of the draft.

That winter, Gaston led the Venezuelan Winter League with a .383 average. The Padres took notice and included the 25-year-old on their Opening Day roster, making him an original Padre. He started the season as a backup, but that situation changed during the first week of the season. Manager Preston Gomez, who liked Gaston, made the rookie his starting center fielder. In particular, the manager loved Gaston’s ability to track fly balls, along with his powerful throwing arm.

On the other hand, Gaston frustrated the Padres with his frequent slumps at the plate. He hit .230 with two home runs, walked only 24 times, and struck out 117 times. He was also bothered by an injury to his foot and an infection in his shin. All in all, it was a rough first season for Gaston wearing the Padres’ brown and white.

Despite the offensive problems, Gomez retained Gaston as his center fielder in 1970. Knowing that his hitting needed to improve, Gaston made some changes. Chicago Cubs star Billy Williams suggested that Gaston change his bat size.

“Billy persuaded me to use a lighter bat,” Gaston told Paul Cour of the Sporting News. “I went from a 35 to a 32-ounce bat, and it gave me a quicker swing.” Richie Allen of the St. Louis Cardinals also offered Gaston some encouragement. And just as importantly, Padres batting coach Bob Skinner, a onetime hitting star in Pittsburgh, retooled Gaston’s swing.

The adjustments and the advice all worked perfectly. Gaston hit .318 with 28 home runs. He won a place on the National League All-Star team, the only selection of his career. Based on his 1970 breakout, the Padres hoped that Gaston had turned the corner and would become a building block for a young team.

It didn’t happen. In 1971, he hit 17 home runs, but his batting average fell by nearly 100 points. He drew only 24 walks. Gaston continued to struggle in 1972, as he moved from center field to right field, in order to accommodate a speedy young outfielder named John Jeter.

Gaston’s situation worsened in the spring of 1973, when Gaston reported to camp weighing 232 pounds. That left Padres president Buzzie Bavasi furious. “He’s 20 pounds heavier than he was three years ago, when he hit .318,” complained Bavasi in an interview with the Sporting News. “He’s spent three weeks trying to get in shape. He should have been in shape when he got here.”

For the season, Gaston would hit 16 home runs, but his batting average fell to .250 and he drew only 20 walks. By 1974, the emergence of other outfielders would start to cut into Gaston’s playing time. The acquisition of veteran center fielder Bobby Tolan, along with the promotion of minor league prospects Dave Winfield and Johnny Grubb, resulted in Gaston spending more time on the bench. It also didn’t help that Gaston turned 30 during the 1974 season.

That winter, the Padres made a trade, sending Gaston back to the Braves in a one-for-one swap involving right-hander Danny Frisella. With a projected starting outfield of Ralph Garr, Rowland Office, and Dusty Baker, the Braves saw no need to use Gaston on an everyday basis. Instead, he became a fourth outfielder, playing mostly against left-handed pitching. For the season, Gaston came to bat 141 times, compiling a respectable OPS of .718.

The marriage between Gaston and the Braves became a good one. He provided the Braves with a defensive caddy for the late innings, while also becoming the team’s top right-handed pinch-hitter. From 1975 to 1978, Gaston filled those roles capably for the Braves.

Late in the 1978 season, with the Braves out of contention, the aging Gaston became trade bait. The Pirates, a contending team in the Eastern Division, inquired about Gaston. On Sept. 22, the Bucs acquired the 34-year-old flychaser in a straight-up cash deal.

Gaston’s career with the Pirates lasted for only the two at-bats. With a surplus of outfielders, the Pirates decided to let Gaston go after the season ended. Gaston accepted a non-guaranteed invite from the Braves, but couldn’t crack their Opening Day roster. Shortly thereafter, he signed on with the Santo Domingo Sugarmakers of the renegade Inter-American League, a new Triple-A venture.

There he enjoyed a reunion of sorts with several former teammates, including Johnny Jeter and Tito Fuentes from his days in San Diego, and Dave May from his time in Atlanta. Gaston batted .328 for Santo Domingo, but the Inter-American League folded up in midsummer, awash in financial problems. From there, Gaston found work with Leon, a team in the Mexican League, where he finished out the season.

After the season, Gaston dropped some excess weight and received an invitation to spring training with the Cleveland Indians. Based on a recommendation from Indians catcher Cliff Johnson, the team gave him a non-roster invite. But he didn’t make the club and returned to Leon in the Mexican League, where he played one more season before finally calling it quits. As it turned out, the 1979 Topps card would be Gaston’s last.

In 1980, Aaron convinced Gaston to return to the Braves’ organization as a minor league hitting instructor. After two seasons on the job, Bobby Cox (who had managed Gaston in Atlanta in 1978) brought him to Toronto as the Blue Jays’ batting coach. Remaining in that post for nearly the rest of the 1980s, Gaston became extraordinarily popular with his players, who loved his open style of communication.

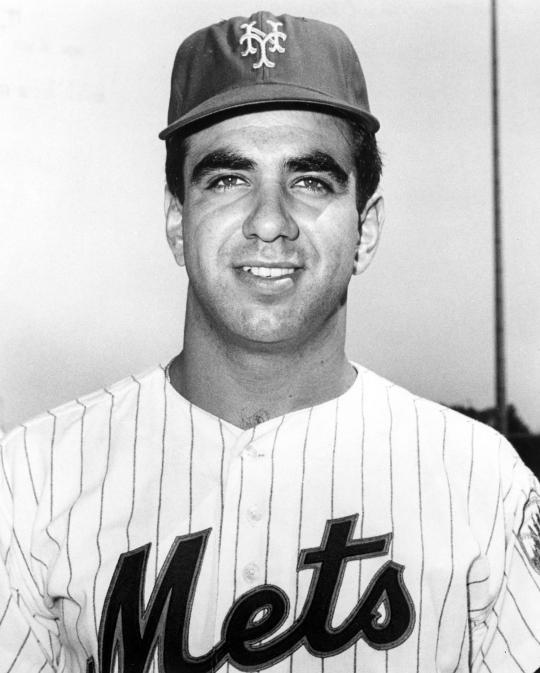

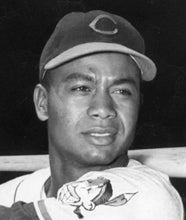

Clarence Gaston was hired as the Blue Jays' hitting coach in 1982, and it was during his time in Toronto that his childhood nickname "Cito" caught on. Gaston later became the Blue Jays' manager, on the enthusiastic recommendation of many of the current Toronto players, and led the team to four divisional titles and two World Series championships. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

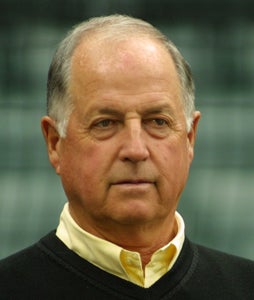

After a bad start to the 1989 season, and with their clubhouse wracked by turmoil, the Jays fired manager Jimy Williams. Initially, general manager Pat Gillick sought Lou Piniella as a replacement, but he was under contract to the New York Yankees. Gillick moved on to Plan B. Several players, including George Bell, Rance Mulliniks and Mike Flanagan, encouraged Gillick to offer the job to Gaston. Gillick accepted the recommendation.

At first Gaston turned down the offer, mostly because he enjoyed his role as the Jays’ hitting instructor. But several of the Jays’ players approached him and encouraged him to take the managerial job. Finally, Gaston agreed. In so doing, he became the fourth African-American manager in major league history, joining Frank Robinson, Larry Doby and Maury Wills.

Known as a players’ manager who excelled at communicating, Gaston sometimes received criticism for being too lenient with his players. He defended his policies in an interview with Vecsey: “I don’t mind if the guys laugh after we lose. They’ve got to get themselves ready for the next day. The same when we win. Enjoy it, but you can’t take it with you. You’ve got to start again tomorrow.”

Gaston’s methods produced results. As he fostered the developments of young talents like Bell, Lloyd Moseby and Jesse Barfield, he led the Jays to five divisional titles and two world championships. The World Series victories of 1992 and ’93 were the first in the history of the franchise.

Now retired from the game, Gaston’s managerial days are behind him. But he has retained his reputation as one of the sport’s nice guys, someone whom you like as soon as you meet him. I learned that first-hand in 2013, when Gaston came to Cooperstown to participate in a panel with Bobby Cox, who once referred to Cito as “one of the nicest human beings I’ve ever been around.” Cox’ words were most accurate. Gaston could not have been friendlier during his Grandstand Theater appearance, both on stage and off.

You can call him Cito. Or call him Clarence. For those who think that “nice guys” can’t win in baseball, Clarence “Cito” Gaston proves that saying is not a hard and fast rule.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame