- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1969 Topps & 1983 Fleer Aurelio Rodríguez

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps & 1983 Fleer Aurelio Rodríguez

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

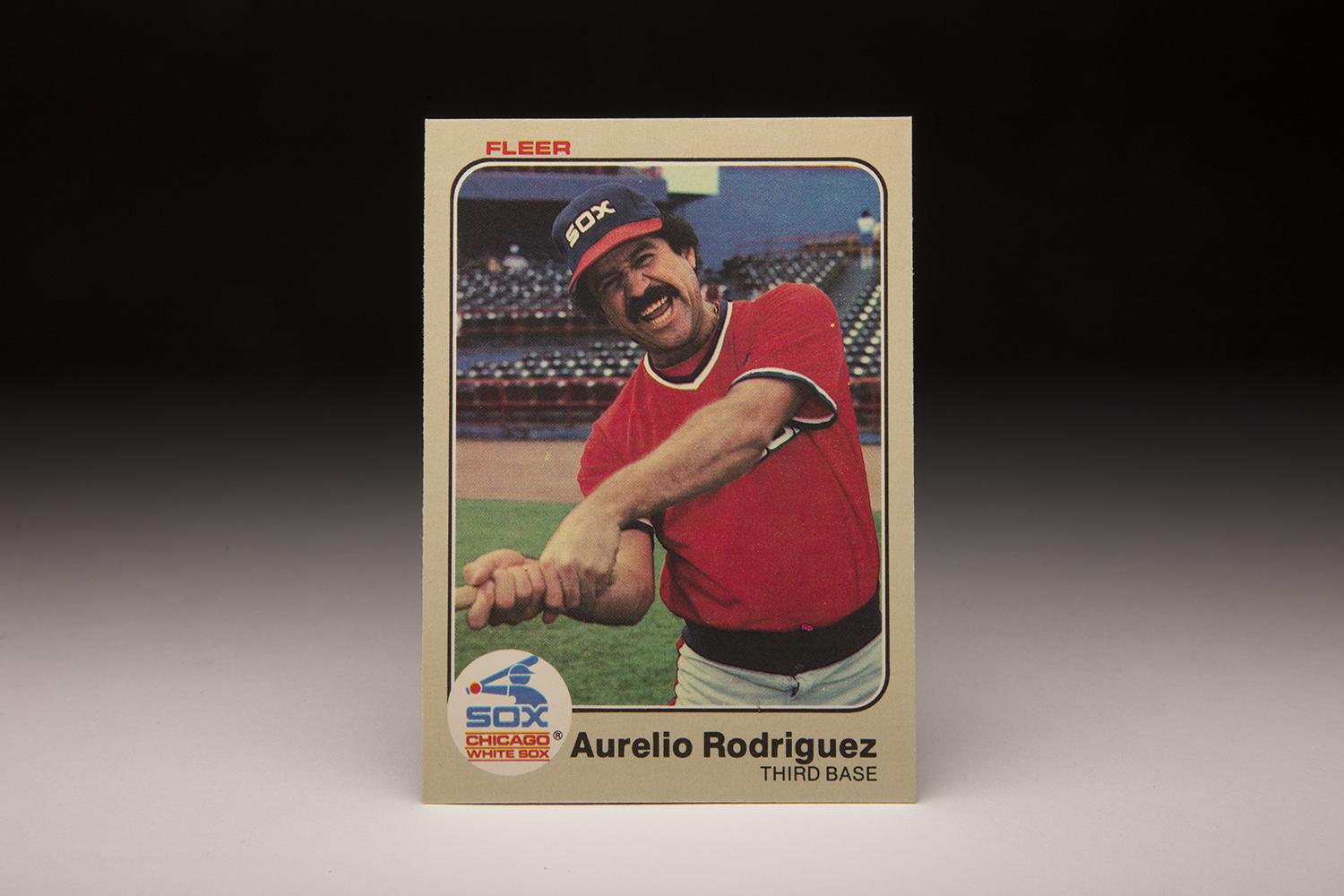

The 1983 Fleer set has become one of my favorites over the years. I like the subtle gray borders, which are reminiscent of what Topps did 13 years earlier, with its 1970 set.

Fleer also made good use of the existing logos for the 26 teams, showcasing them in the lower left-hander corner, and allowing the logos to identify each team. And the ’83 Fleers show a dash of creativity, with the photographers willing to include some interesting props and unusual backdrops to the standard array of posed field shots and action photographs.

A few cards stand out from 1983 Fleer. I’ve previously written about the Johnny Grubb card, which shows the Texas Rangers’ outfielder proudly holding a cup of “Ranger Ade.” The Pete Falcone card is unusual, too; taken in the clubhouse, the photo shows the New York Mets’ left-hander sitting on a stool holding up his 1981 Fleer card. And then there’s the 1983 Rick Mahler card, where we see the Atlanta Braves’ right-hander standing in a dark room with boxes of baseballs, which he has presumably been asked to sign.

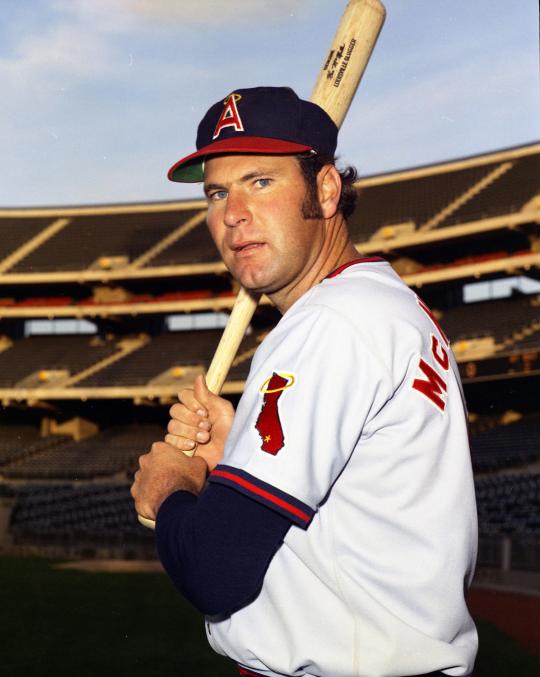

In at least one case, a photographer from Fleer managed to elicit an unusual facial expression from his subject. We see the evidence of this on Aurelio Rodriguez’ 1983 card. As Rodriguez feigns a practice swing for the camera, he appears to be letting out a yell, or at least a growl. Rodriguez’ mouth is in full grimace, but he includes just the hint of a smile, so as to make it clear that he is being playful and prankish, rather than legitimately angry or upset.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Whether Rodriguez staged this display on this own, or at the prompting of the photographer, is something that remains unknown to us. But it really doesn’t matter. All that matters is that Rodriguez is having fun, and if you can’t have fun while posing for your baseball card, then when can you?

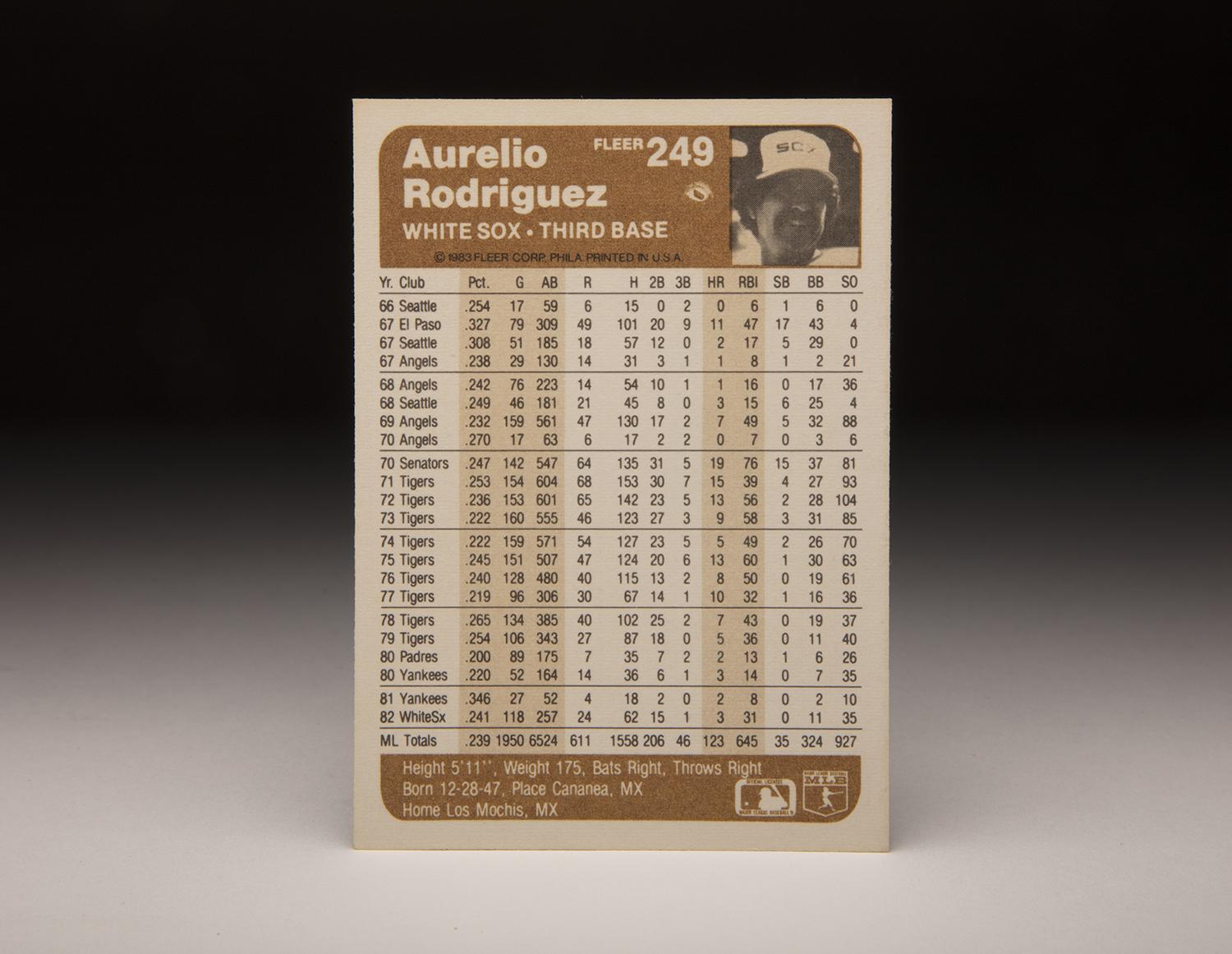

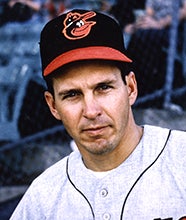

The 1983 Fleer card is one of the final cards produced for Rodriguez (his final card coming out in 1984 from Topps). His long professional career stretched all the way back to the mid-1960s. Originally a fledgling player in the Mexican League, Rodriguez drew some interest from the California Angels, who reached an agreement with the Jalisco Charros, his team in Mexico. At the time, Jalisco also featured future major league catcher Elrod Hendricks and former big league star Minnie Minoso. For a small sum of cash, Jalisco agreed to send Rodriguez to the Angels.

The Angels did not promote Rodriguez to the big league club right away. Instead, they assigned him to their Triple-A affiliate at Seattle, where he appeared in a handful of games in August and September of 1966. Initially, Rodriguez struggled with American culture. When he reported to Seattle, he knew all of three words in English: “Ham and eggs.” That was the food combination that he ordered at every meal, resulting in a diet that was not exactly well rounded.

“I ate so many eggs, I was beginning to feel like a chicken,” Rodriguez said jokingly in an interview that appeared in the Tigers’ 1977 Yearbook. “I had them every way – scrambled, poached, and fried.”

The following spring, Rodriguez began to diversify his diet at Double-A El Paso, where the Angels assigned him. He also showed that he was more than capable of handling pitching at that level. In roughly a half-season, he batted .327 with 11 home runs. That was more than enough proof to the Angels that Rodriguez deserved another promotion to Seattle, where he batted .308 in 51 games. The Angels deemed him worthy of a late-season recall, bringing him up in September and playing him every day at third base.

Rodriguez didn’t hit much during that month-long trial, but his fielding at third base opened eyes. Still, the Angels sent him back to Triple-A to start the 1969 season, before giving him a second look in California, Appearing in 76 games at third base and second base, Rodriguez again struggled with the bat, hitting only .242 with one home run.

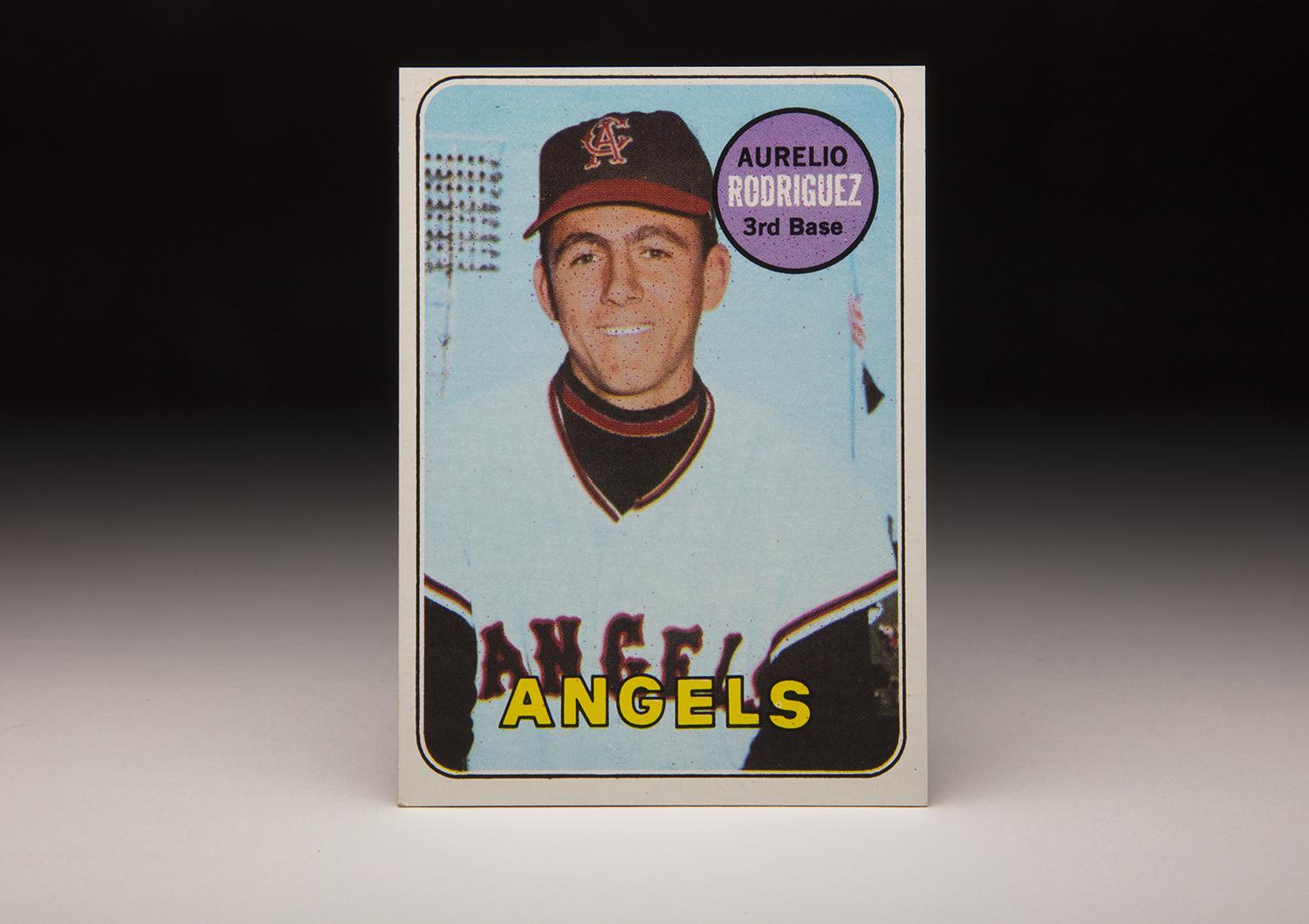

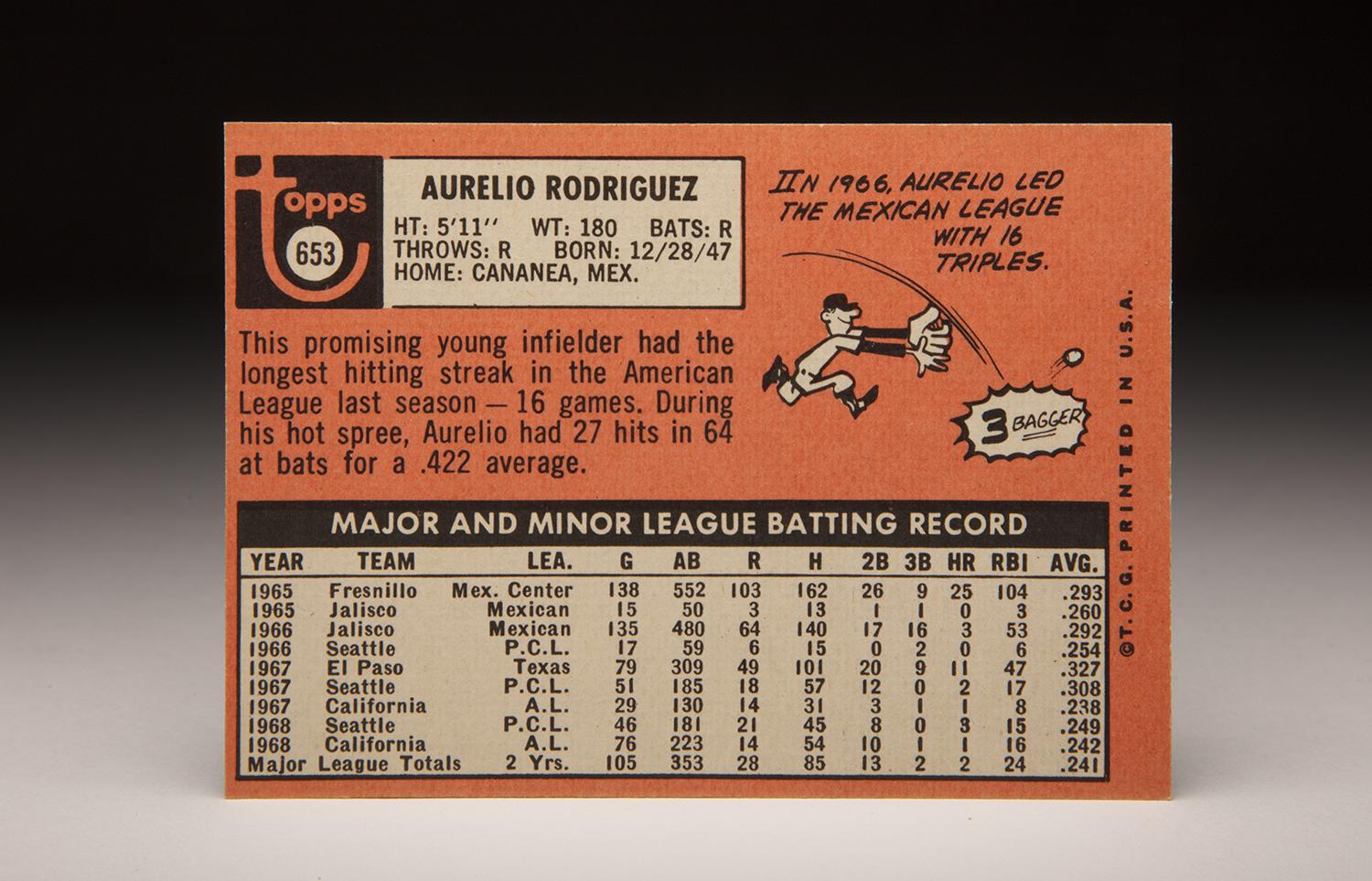

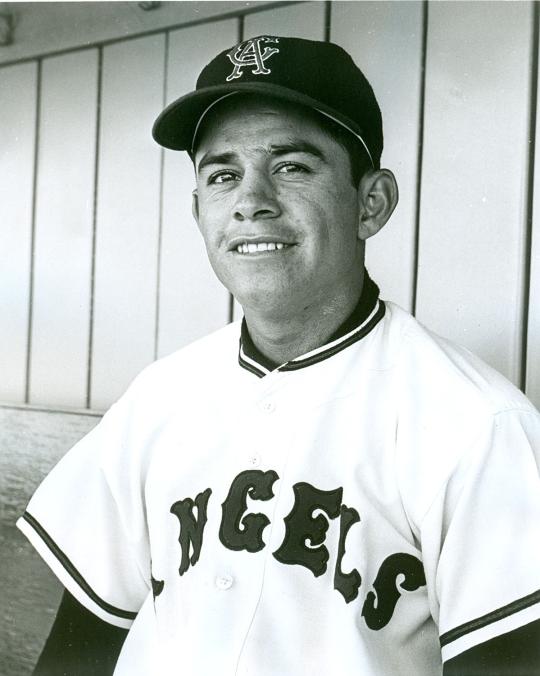

As difficult as Rodriguez found life to be in the batter’s box, the Angels loved his glove at the hot corner, a position that had become problematic for California. In 1969, he assumed the starting role on Opening Day. His 1969 Topps card also became a source of attention, when some collectors noticed the photograph on the front of the card. The picture did not depict Rodriguez at all; in later years, the young man on the card would come to be identified as Leonard Garcia, the Angels’ batboy who happened to look a little like Rodriguez.

For years, the 1969 Rodriguez card became a source of debate, with some in the industry claiming that the young third baseman had pulled a prank on Topps. Yet, there was no such evidence to indicate that Rodriguez had done anything nefarious. It is now generally believed that Topps somehow mixed in a photograph of batboy Garcia with the other photos in the Rodriguez file. Topps chose the Garcia photo, not realizing that he was the batboy, and not the Angels’ third baseman. In actuality, the error was somewhat understandable, because Garcia and Rodriguez did share some common facial traits.

Card controversies aside, Rodriguez showed a little more power in 1969, but the rest of his offensive game lagged behind. His seven home runs represented an improvement, but his .579 OPS left something to be desired, especially at a position where teams preferred run production.

Angels manager Lefty Phillips tried to work with Rodriguez, encouraging him to use the opposite field in his approach to hitting. But Rodriguez, who tired of Phillips’ constant refrain, showed himself unwilling to take the advice, instead trying to pull most pitches. Infatuated with the long ball, Rodriguez preferred taking aim at the left field fences, but his approach resulted in too many strikeouts and too few home runs.

Rodriguez began the 1970 season with the Angels, but his California tenure came to an end before the end of the first month. On April 27, the Angels opted for a more established hitter at third base, acquiring veteran Ken McMullen from the Washington Senators. In return, the Angels packaged Rodriguez with Rick Reichardt, their onetime bonus baby who had failed to live up to expectations in Southern California.

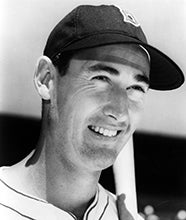

The move to Washington turned out to be the perfect tonic for Rodriguez, who was now afforded the chance to play for Ted Williams. The Senators’ manager worked wonders with Rodriguez, who responded by hitting 19 home runs and improving his slugging percentage to .426. Rather than tinker with Rodriguez’ swing, Williams encouraged him to offer only at good pitches within the strike zone, while emphasizing the importance of bearing down during each at-bat. As an added bonus, Rodriguez surprised everyone by stealing 15 bases. Just like that, the Senators appeared to have found a young third baseman who could fill the position for years to come.

Rodriguez seemed like a long-term solution for Williams and the Senators, but team owner Bob Short had other plans. Given a chance to acquire a name-brand player like Denny McLain from the Detroit Tigers, Short couldn’t resist the temptation. He felt that McLain, a two-time Cy Young Award winner, would boost attendance at RFK Stadium. So Short packaged Rodriguez with slick-fielding shortstop Eddie Brinkman and pitchers Joe Coleman and Jim Hannan, sending them all to Detroit for McLain, third baseman Don Wert, outfielder Elliott Maddox and pitcher Norm McRae.

McLain would flop in Washington, but Rodriguez and Brinkman would form a nearly impenetrable left side of the Tigers’ infield. It did not take long for Rodriguez to win favor from his new manager in Detroit, Billy Martin.

“The young guy’s a battler all the way,” Martin told Watson Spoelstra, corresponding for the Sporting News. Rodriguez also responded to Martin’s persistent instruction, by consistently hitting behind the runner to the opposite field and becoming skilled at dropping down squeeze bunts.

After a smooth transition to Detroit in 1971, Rodriguez helped the Tigers win the American League East by one game in 1972. He didn’t hit much that summer (a .236 batting average and a .628 OPS), but he played an impeccable third base for Martin. With his soft hands, shortstop-like range, and cannonlike throwing arm, Rodriguez continued to build on his reputation for fielding excellence.

Rodriguez’ defensive play remained at a high level in the 1972 ALCS, but his batting continued to lag. He went 0-for-16 against the vaunted pitching staff of the Oakland A’s, a level of futility that became more frustrating in light of the Tigers being eliminated in five games.

Over the next two seasons, Rodriguez’ offensive game bottomed out. He batted .222 each season and failed to reach double figures in home runs. He then incurred the anger of general manager Jim Campbell when he reported to Spring Training late in 1975.

“You’d think, when a guy is a .220 hitter, he’d show up two days early,” Campbell said in a testy interview with the Sporting News. But Rodriguez showed up one day later, quickly making Campbell forget why he was mad. And then Rodriguez enjoyed a bounceback season, batting .245 with 13 home runs.

For most of his career, the Gold Glove Award eluded Rodriguez, mostly because of the simultaneous presence of Brooks Robinson and Graig Nettles in the American League. Robinson won the award exclusively over the first half of the 1970s, while Nettles would take home the award in 1977 and ’78. That pattern changed in 1976. Appearing in 128 games, Rodriguez made only nine errors. After the season, the writers voted him the Gold Glove Award for the first and only time in his career.

After a lackluster 1977 season, Tigers manager Ralph Houk announced that Rodriguez would platoon with young Phil Mankowski to start the 1978 campaign. Rodriguez responded to the new role by embarking on a remarkable tear at the plate. By the end of April, Rodriguez was hitting .400, good enough to lead the American League in batting average.

Rodriguez did cool off later in the summer, but still managed to bat .265 for the season, his best mark for a full year. The downside was a lack of power; Rodriguez hit only seven home runs.

After injuries limited Rodriguez to just over 100 games in 1979, the Tigers decided to make a move. Over the winter, they sent Rodriguez, their respected veteran leader, to the San Diego Padres. The Padres surrendered only cash in return. The trade left some members of the Tigers’ pitching staff in praise of their departed infielder.

“I know how much the pitchers will miss him,” right-hander Milt Wilcox told Tom Gage, corresponding for the Sporting News. “We didn’t take him for granted. Some people said he had lost a step, but as far as I’m concerned, he’s still a very good third baseman.”

In contrast to his role in Detroit, Rodriguez spent most of his time in San Diego as a defensive caddy. In August, with the Padres out of contention, they sent Rodriguez to the New York Yankees, who needed help at third base because of an injury to Nettles. Rodriguez didn’t hit much for the Yankees down the stretch, but did pick up two hits in six at-bats in the 1980 ALCS. He would have a far larger impact in 1981. The Yankees played him only occasionally, and almost exclusively against left-handed pitching, but Rodriguez delivered. He came to bat 52 times, batting .346 and slugging .500. He also played his usual impeccable third base.

In the World Series, Rodriguez took on a greater role as a fill-in for the injured Nettles and tormented the Los Angeles Dodgers with five hits in 12 at-bats. His performance fell into obscurity, however, overshadowed by the Yankees’ six-game loss to the Dodgers, not to mention a celebrated fight that owner George Steinbrenner supposedly engaged in with some Dodgers fans during an elevator ride.

As a role player, Rodriguez more than did his job for the ’81 Yankees. And then strangely, the Yankees rewarded that performance by trading their veteran third baseman over the winter, sending him to the Toronto Blue Jays for a non-prospect named Mike Lebo. The Jays announced that Rodriguez would become their everyday third baseman, but he would never play a single game for the franchise. Instead, one week before Opening Day, they dealt him to the Chicago White Sox for outfielder Wayne Nordhagen.

From there, Rodriguez moved on to the Baltimore Orioles, where he served as a tutor to young third baseman Leo Hernandez, before returning to the White Sox to finish his big league career in 1983.

Although his stateside playing career had ended, Rodriguez continued to play in the Mexican League, where he became a legendary figure, first as a player and then as a manager. He also did work for the Arizona Diamondbacks as a minor league hitting instructor, an ironic choice given his proficiency for defense.

While employed by the D-Backs in 2001, Rodriguez made an offseason trip to Detroit, where he was scheduled to take part in a signing with one of his former Tiger teammates, Tom Brookens. Rodriguez was walking on a Detroit sidewalk with a female companion when a car veered off the road – the result of the driver suffering a stroke. After jumping the curb, the car crashed into Rodriguez and the woman. The freakish accident killed the 52-year-old Rodriguez, who never made it to the signing with Brookens.

In his native Mexico, Rodriguez’ death became a huge national story. His funeral drew thousands of well-wishers, including Mexican president Ernesto Zedillo. In Detroit, Rodriguez’ death also left an impact, given his status as one of the city’s first prominent Latino citizens.

Aurelio Rodríguez played for the California Angels for the first four seasons of his career (1967-70). (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

It’s always jarring to hear about a former major leaguer, one whom I saw play, passing away so unexpectedly, especially under such horrible circumstances. It’s even tougher when that player brings back such an array of fond imagery, from that howitzer of a throwing arm to those wonderful baseball cards from 1969 and 1983. I only wish that I had the opportunity to meet Mr. Rodriguez.

In this case, all I have are the baseball cards, and the fun memories that come with them.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame