- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: Topps 1983 Woodie Fryman

#CardCorner: Topps 1983 Woodie Fryman

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

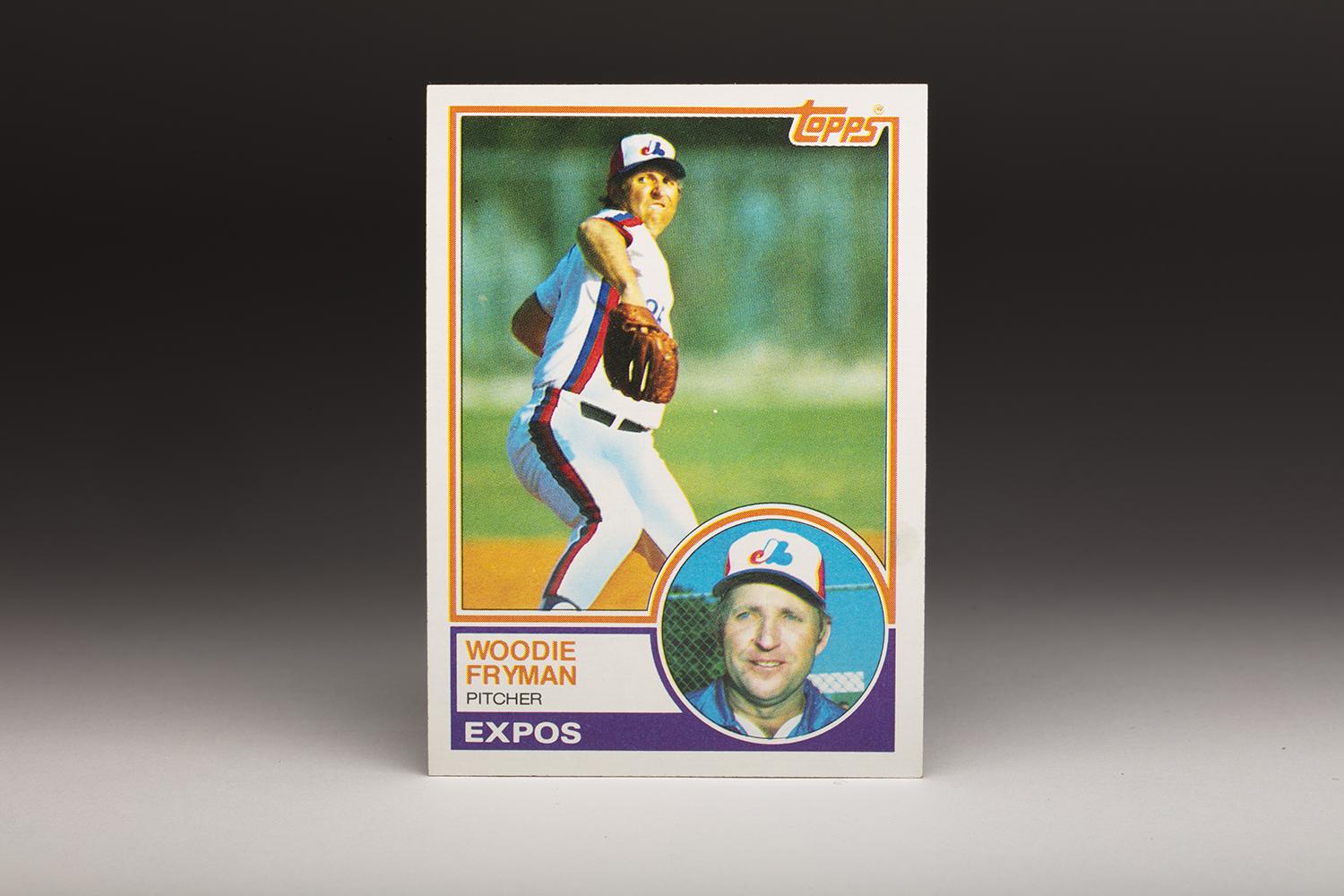

When a card captures a player just right, it’s almost a mystic experience for a card collector. The photograph gives us characteristics unique to the player, bringing back an image of the player in just the way that we first recalled him. The Topps Chewing Gum Company delivered one of those cards in 1983, when it issued its final card for longtime left-hander Woodie Fryman.

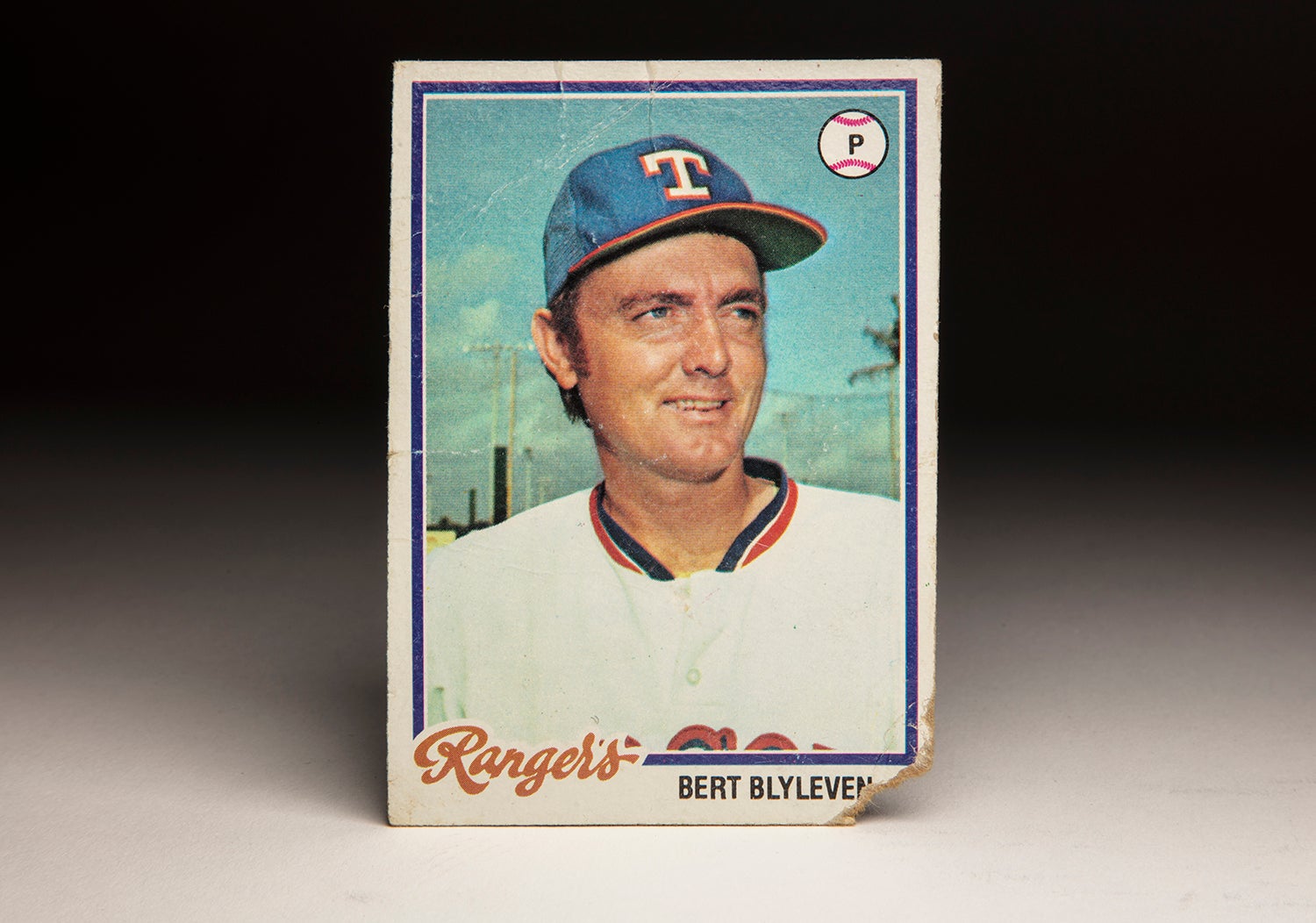

At 42 years of age, Fryman did not feature the physique of a Jim Palmer or a Bert Blyleven. He had the kind of thick paunch and heavy legs that looked like they were better suited to working on a farm than working off a mound. Thanks to the dual photographs on his 1983 Topps card, we are given a glimpse of his ample midsection (through the action shot) and a closer look at his ruddy, weathered face (through the portrait in the corner).

The larger photo captures Fryman in the midst of delivering a pitch for the Montreal Expos, likely during a Spring Training game in 1982. Notice the intense grimace on his face, in which he practically appears to be biting his lip, as he releases the ball toward an unknown batter. It’s a perfect representation of Fryman, who in his later years was known for rearing back and throwing as hard as he could. In pumping fastball after fastball toward home plate, Fryman supplied maximum effort, which is fully evident in this shot from Topps.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

For me, the name of Woodie Fryman brings back good memories, dating back to a game in the later stages of 1973. But Fryman’s baseball story began nearly a decade earlier, in 1965, when the Pittsburgh Pirates signed the seemingly unwanted left-hander to his first professional contract. Five years earlier, the Pirates had given Fryman a tryout after scouting him in a semi-pro league. The Pirates offered Fryman a contract back then, but the youngster wanted a bonus of $20,000. When the Pirates refused the bonus, Fryman told them he wasn’t interested. Later on, he negotiated with several other teams, but whenever Fryman asked for a bonus, he was rejected. Believing that teams were taking advantage of him, in part because they knew that Fryman had only an eighth-grade education, he refused to budge on his demand of $20,000.

Fryman returned to his family’s home in Ewing, Ky., where he continued to work on the family’s 40-acre tobacco farm. He remained there for a few years, at least until the U.S. government curtailed subsidies for tobacco farmers.

Fryman and his father approached the Pirates again, this time with Woodie agreeing to a more modest contract and an assignment to Batavia of the New York-Penn League. Upon the recommendation of Pirates scout Jim Maxwell, Fryman lied about his age. He told the Pirates that he was born in 1943, cutting three years off his actual age and giving the Pirates every impression that he was only 22, and not 25.

Far more mature than most of the players in the league, Fryman moved up quickly. After a handful of games at Batavia, he received a promotion to Triple-A Columbus, the Pirates’ top affiliate in the International League. Fryman started six games for the Clippers and didn’t win any of them, but showed enough life with his left arm to merit a Spring Training invite in 1966, despite being a non-roster player.

Fryman’s first Spring Training with the Pirates turned out successful. The Pirates badly needed a left-handed reliever and looked to Fryman, who did not allow a single hit during the exhibition season. Fryman made the Opening Day roster and did so well out of the bullpen that he quickly moved into the rotation. Taking his regular turn in a group that featured Bob Veale, Vernon Law, and Steve Blass, Fryman won 12 games and struck out 105 batters in 181 innings.

The second time around, Fryman did not fare as well against National League batters. Bothered by a bad arm, he lost his spot in the rotation, saw his ERA rise above 4.00, and won only three games. Giving up quickly on the hard-throwing left-hander, the Pirates decided to include him in a major deal that winter. They sent Fryman and prospects Don Money and Bill Laxton to the Philadelphia Phillies for future Hall of Fame right-hander Jim Bunning.

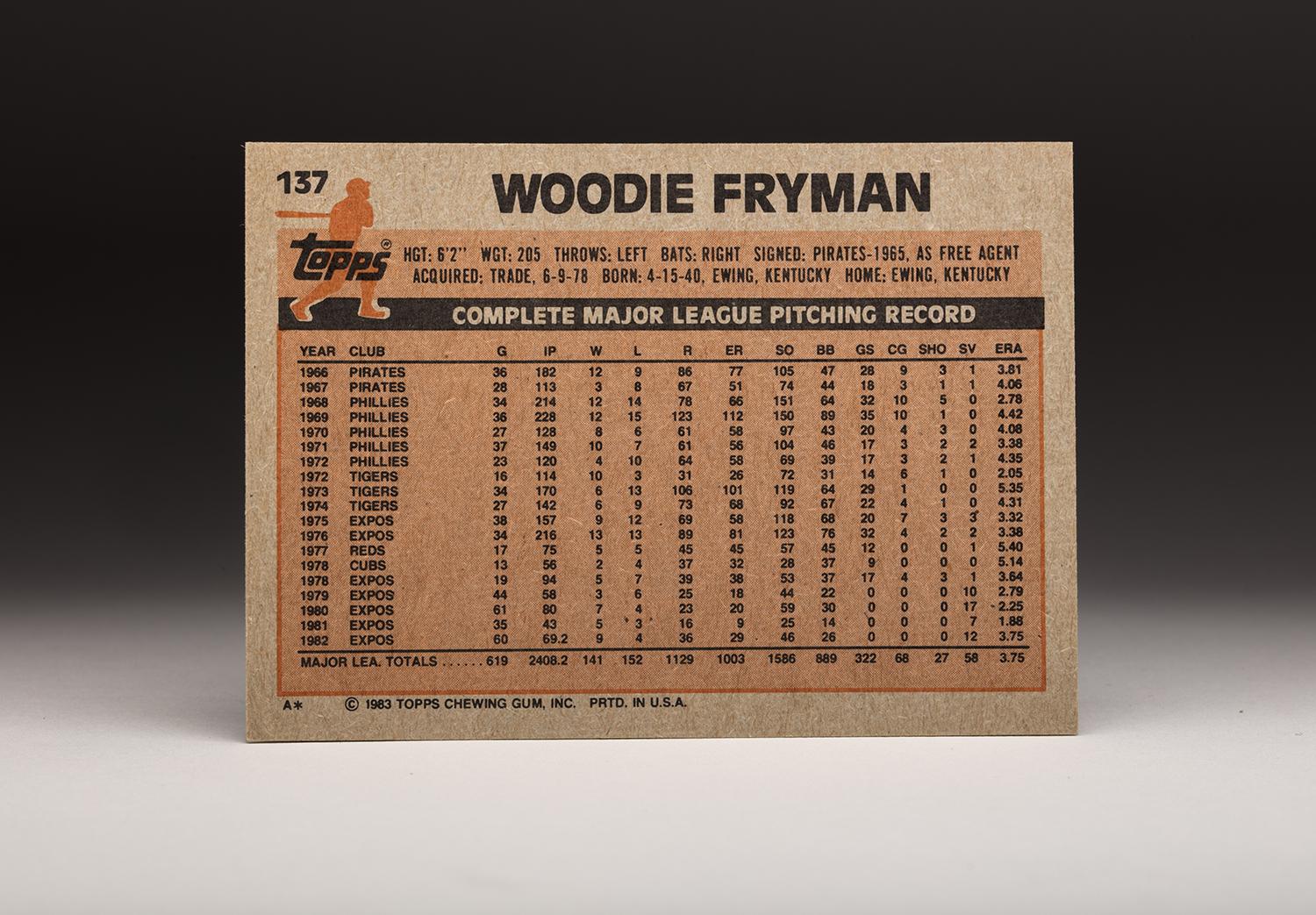

Phillies manager Gene Mauch was as excited as anyone when he heard about the acquisition of Fryman, whose live left arm made him coveted among National League scouts. “I know Woodie can throw,” Mauch told the Sporting News. “Nobody in the business can throw any better.” Fryman took well to the Phillies, lowering his ERA to 2.78 in his first season with Philadelphia, while striking out 151 batters in 213 innings. Fryman’s first half performance earned him a berth on the National League All-Star team, the first of two selections during his career.

Fryman’s ERA rose above 4.00 over the next two seasons, in part because of the lowering of the pitcher’s mound and in part because of injuries that curtailed his performance in 1970. But he bounced back in 1971, as the Phillies moved him into a role as a combination starter/reliever. Fryman responded well to the change. He won 10 of 17 decisions and sported an ERA of 3.38.

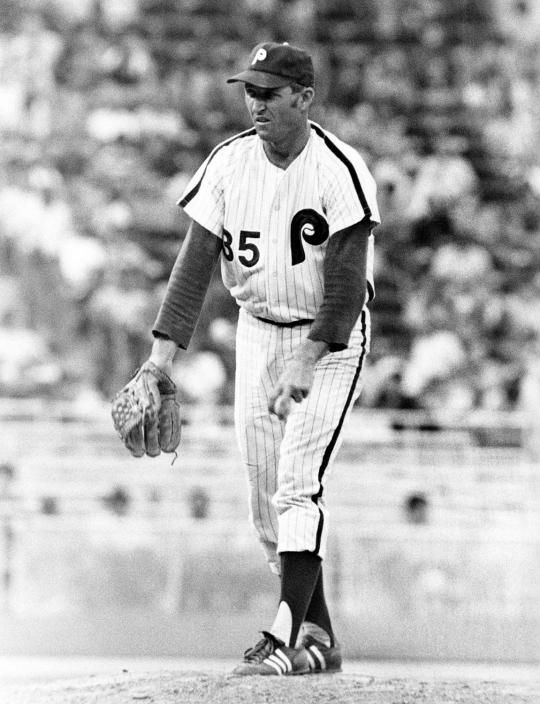

Then came the difficult season of 1972. The Phillies, in the midst of a rebuilding program, had an awful team. When Fryman struggled at the outset, the Phillies decided that it was time to move their 32-year-old left-hander. The Phillies placed him on waivers in August, hoping that he would not be claimed by any team, which would then allow him to be traded. But the Detroit Tigers, contending for the American League East title, put in a claim. Rather than pull him back from waivers, the Phillies allowed the Tigers to claim Fryman for the meager waiver price of $25,000.

Just that inexpensively, without having to surrender any talent in return, the Tigers had found themselves a quality veteran starter. The move would pay major dividends for the Tigers. Fryman went 10-3 with a 2.06 ERA down the stretch in ‘72, helping lift the Tigers to a half-game win over the Boston Red Sox in a fragmented, strike-shortened pennant race. Prior to Fryman’s arrival, the Tigers had only two reliable starters in Mickey Lolich and Joe Coleman. With the addition of Fryman, Martin now had three options that gave him a better than even chance of winning on a given day.

General manager Jim Campbell’s waiver claim of Fryman saved the season for the Tigers. Without the wily southpaw, who won seven of his last eight decisions and posted a pennant-clinching win over the Red Sox, the Tigers would have settled for a second-place finish.

Fryman did not fare as well in the American League Championship Series, where he lost two starts to the Oakland A’s, but those losses were more of a case of hard luck than poor pitching. In 12 innings against the eventual world champions, he struck out eight batters, walked only two, and posted a respectable ERA of 3.65.

The following year, I had the chance to see Fryman in person at Yankee Stadium. It was September of 1973, when my father took me to a late-season game between the Tigers and the Yankees. It was one of the first games that I ever attended. In fact, it was the final night game in the history of the original Yankee Stadium. My father and I talked a lot about Woodie Fryman that night, about how he was a good, veteran left-hander who knew how to pitch.

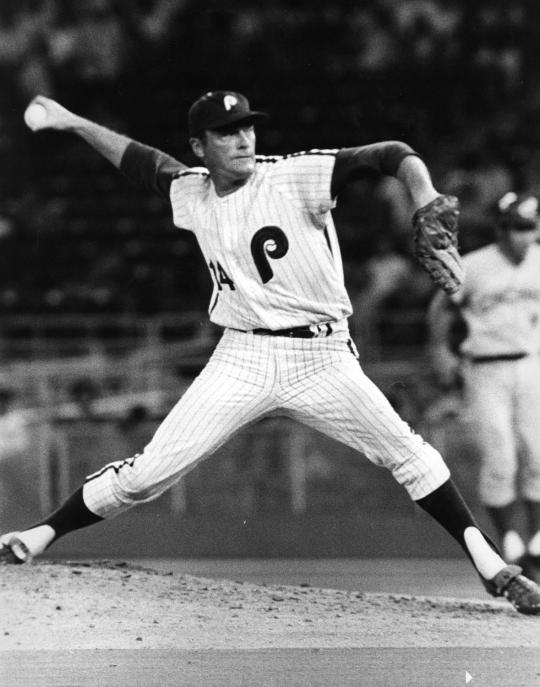

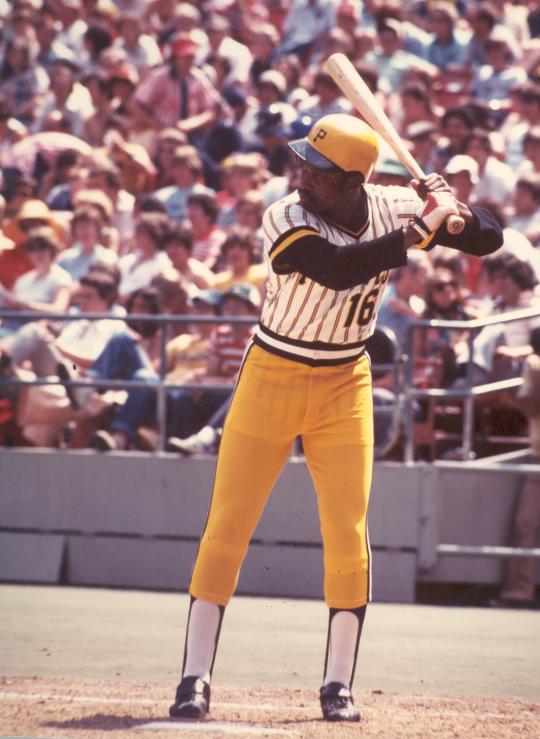

I remember that Fryman used an old-time windup, swinging both his arms behind his head, and then managing to hide the ball near his waist just before releasing the pitch. He also tended to drag his left food on the mound, a habit that resulted in horrible blisters to his feet. Al Oliver, the standout hitter for the Pirates who faced Fryman during their National League days, once told me that he simply hated having to face Fryman and that deceptive delivery. Fryman not only had a good fastball, but he featured a tough slider that made life miserable for left-handed batters.

Fryman was a throwback in other ways. During his days in Philly, he was diagnosed with arthritis in his left elbow. He pitched the rest of his career with the condition (and those painful foot blisters), yet rarely complained about the pain it caused or allowed it make an excuse for a poor performance. Even with arthritis, Fryman would last 18 seasons in the major leagues.

In 1974, Fryman would struggle for the Tigers, the condition of his elbow limiting him to 22 starts. Even as his pitching waned, he remained popular with teammates, one of whom, a utility infielder named John Knox, affectionately called him “Old Goat.” But Fryman’s declining performance led to a wintertime trade. The Tigers sent him to the Montreal Expos for two players, catcher Terry Humphrey and pitcher Tom Walker (the father of current New York Mets second baseman Neil Walker.) Fryman posted two good seasons in Montreal, but the Expos couldn’t pass up the opportunity to acquire Hall of Fame first baseman Tony Pérez from the Cincinnati Reds, so they included Fryman and reliever Dale Murray in the return trade package.

At first, Fryman received the news of the trade well, because of Cincinnati’s close proximity to his farm in Kentucky. But the trade of Pérez was unpopular with Reds fans, who took out their disapproval on Fryman. The Reds needed pitching badly, especially after the loss of Don Gullett to free agency, and made Fryman their Opening Day starter in 1977, ahead of quality starters like Jack Billingham and Fredie Norman. Fryman struggled at the outset, lost his job in the rotation, and soon found himself pitching as a spare part out of the bullpen. Unhappy with his lack of work, he stunned the Reds in mid-July by announcing his sudden retirement. Fryman left the team and returned to his family farm.

Fryman was not the stereotypical ballplayer who kept late hours at local watering holes. In fact, he did not like the nightlife, instead preferring going to bed early and rising at dawn. Given those preferences, it should not have come as a major surprise that he left the game – at least temporarily – to engage in country life.

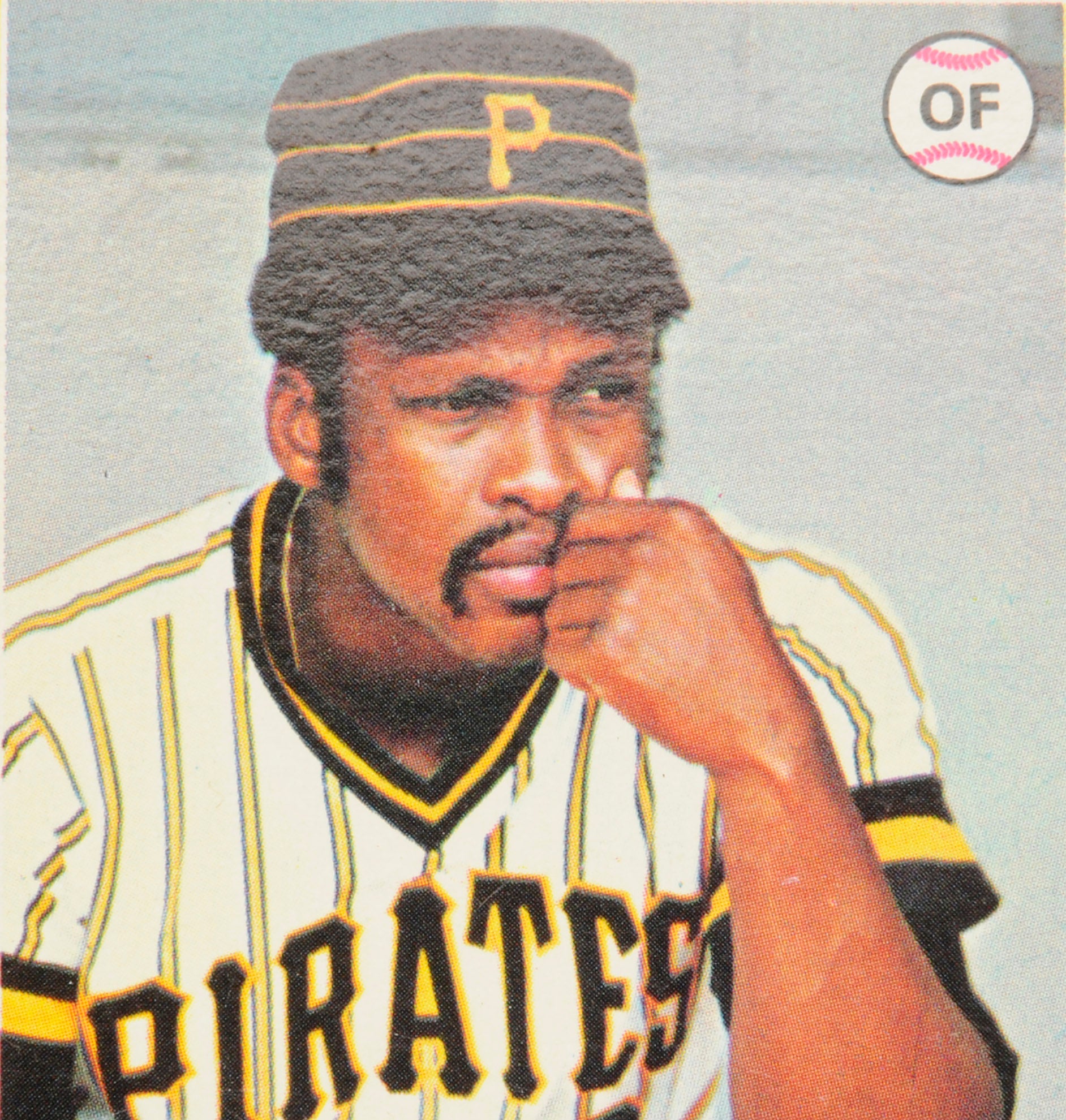

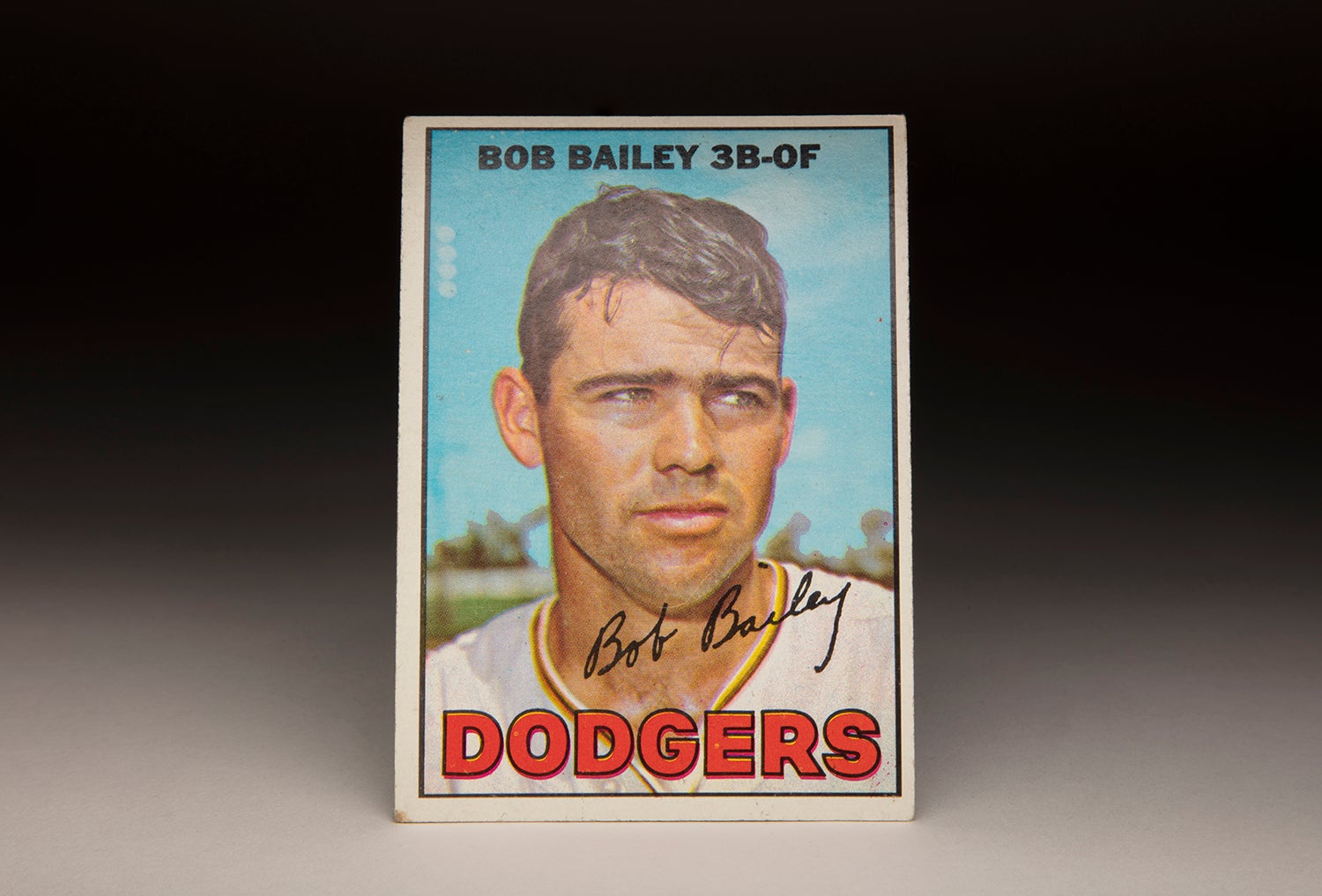

After the Pittsburgh Pirates sent Woodie Fryman to the Philadelphia Phillies as part of a four-man deal, Fryman saw success in his first season, lowering his ERA to 2.78. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Future Hall of Famer Jim Bunning was sent to the Pittsburgh Pirates as part of a trade that sent Woodie Fryman to the Philadelphia Phillies. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

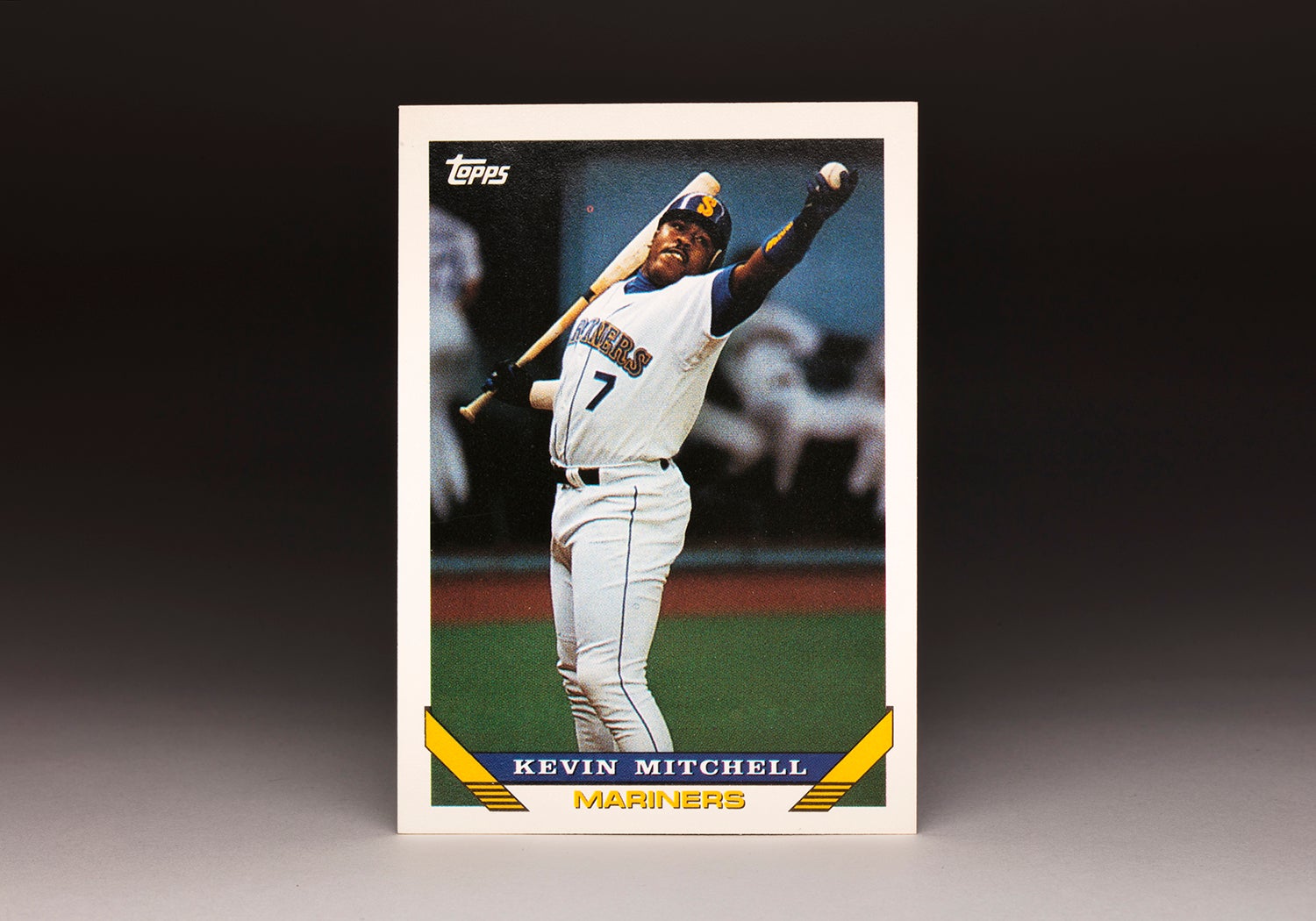

Woodie Fryman was selected off waivers by the Detroit Tigers halfway through the 1972 season, and went on to go 10-3 with a 2.06 ERA for the team that year. (Richard Raphael / National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Al Oliver, an outfielder and first baseman for the Pittsburgh Pirates pictured above, said that batting against Woodie Fryman was difficult because of the pitcher's deceptive delivery. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Hall of Fame manager Dick Williams, pictured above, made Woodie Fryman a full-time Expos reliever in 1979, a move that quickly paid off. Fryman quickly became Montreal's No. 1 left-hander in the bullpen, posting an ERA of 2.34 and 34 saves over the next three seasons. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Although Woodie Fryman posted two good seasons in Montreal in 1975 and ’76, the Expos dealt him to the Reds in exchange for future Hall of Fame first baseman Tony Pérez following the 1976 season. But by 1978, Fryman was back in an Expos uniform, where he became one of the game’s top left-handed relievers. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

That winter, the Reds traded Fryman to the Chicago Cubs. He agreed to report to Chicago, but spent a miserable half-season there as a utility pitcher. A week before the trading deadline in 1978, the Cubs traded him back to Montreal, where he began his second stint with the Expos. Fryman took his place in the Montreal rotation, but he pitched unimpressively. Expos manager Dick Williams, often a man of foresight, made Fryman a full-time reliever in 1979, and the move turned out splendidly. For the next three seasons, he was virtually untouchable as Montreal’s No. 1 left-hander in the bullpen, where he shared closer duties with Elias Sosa and a young Jeff Reardon. Fryman became something of a cult figure in Montreal, as popular as any player on the team.

Fryman remained a quality pitcher through the 1982 season. After six ineffective appearances in 1983, Fryman felt something in his arm pop. Suddenly, he couldn’t raise his arm above his shoulder. He knew then and there that it was time to retire – at the age of 43. With his protruding midsection, round face, and gray hair, Fryman looked more like 53, causing teammate Ken Macha to playfully refer to him an as “an overstuffed geezer.” While it’s true that Fryman had an unusual physique, he also outlasted most other players who had entered the big leagues in 1966, the year of his debut.

After his playing days, Fryman retired to his tobacco farm in Kentucky. He considered himself a tobacco farmer first and a ballplayer second. “Farming is all I ever wanted to do,” Fryman once told George Vecsey of The New York Times. He just happened to be a farmer who could throw a ball through a wall.

Fryman continued to work his farm until his health would no longer allow it. Stricken with Alzheimer’s disease and heart problems, he died in 2011 at the age of 70. When I heard about his death, I immediately thought back to that night at the old Yankee Stadium in 1973, when my dad took me to the ballpark for one of the first times that I could remember. I also thought about some of Fryman’s baseball cards, where he looked more like a character out of Green Acres or Petticoat Junction than a pitcher who could throw in the mid-nineties.

Woodie Fryman was both a farmer and a fireballer, and just so happened to be very good at both. I guess that’s just another reason why baseball is the great game that it is.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum