- Home

- Our Stories

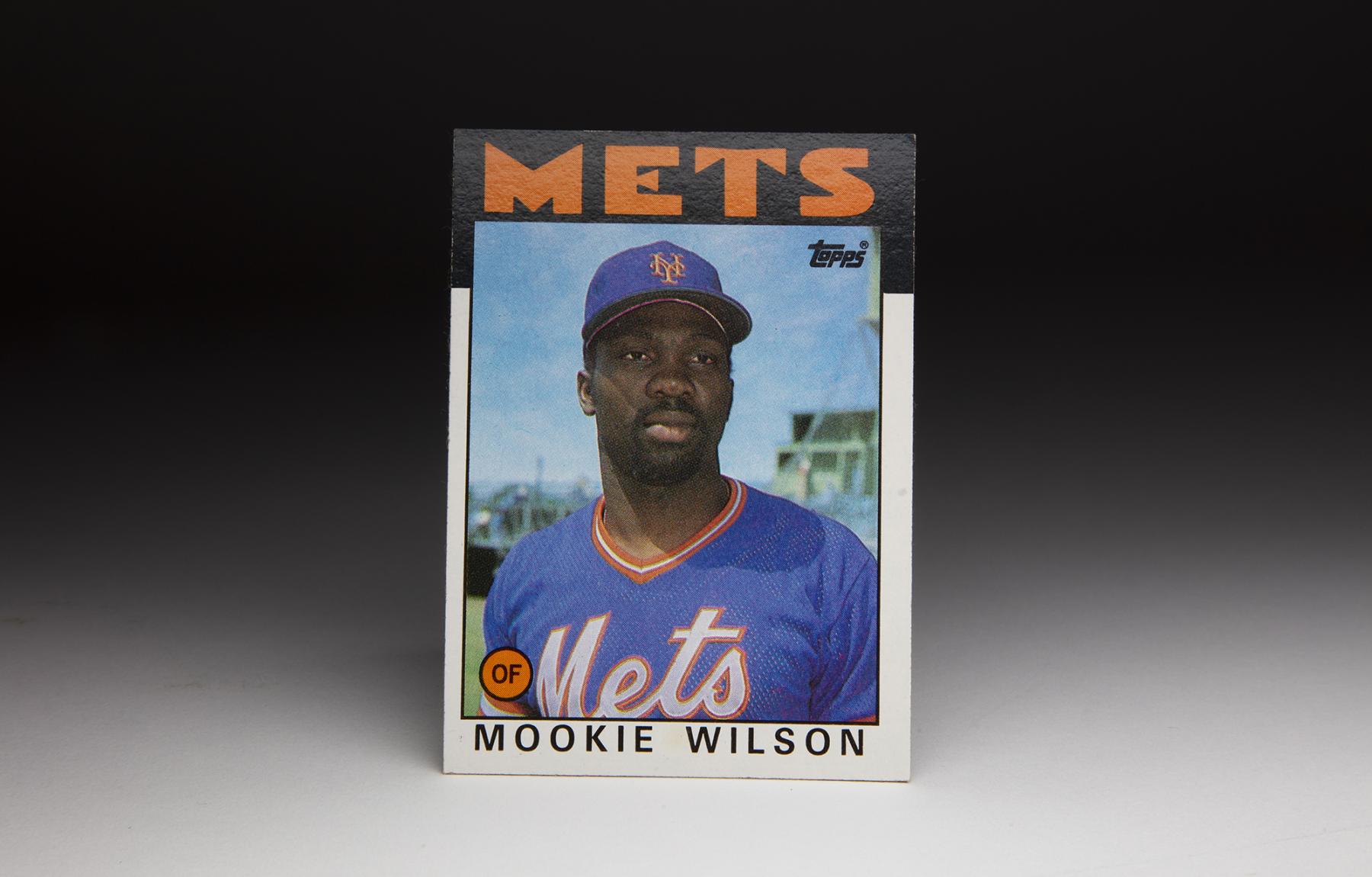

- #CardCorner: 1986 Topps Mookie Wilson

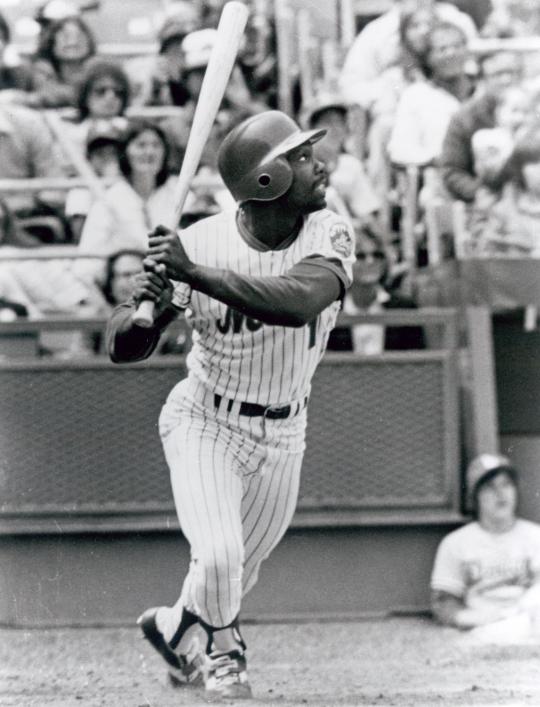

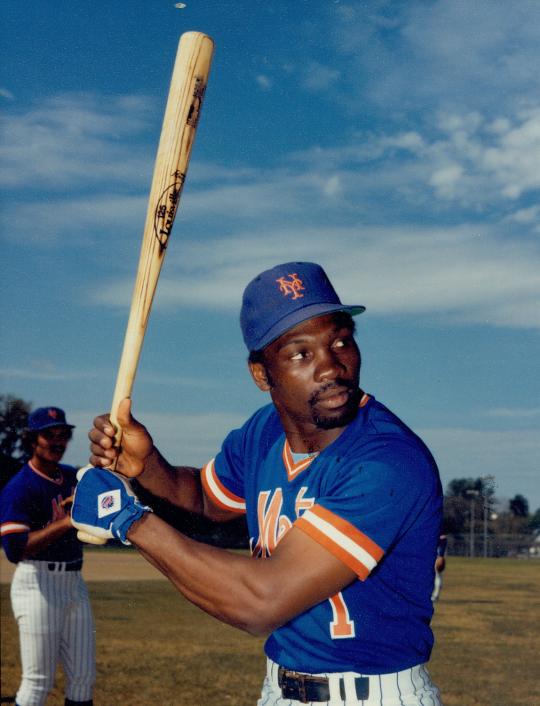

#CardCorner: 1986 Topps Mookie Wilson

It is a moment in baseball lore defined by the losing team, specifically a first baseman who was unable to corral what appeared to be a simple ground ball.

Bill Buckner’s glove was the story on Oct. 25, 1986, in Game 6 of the World Series. But Mookie Wilson was the player who set history in motion, carving in granite a tale that will be told as long as the game is played.

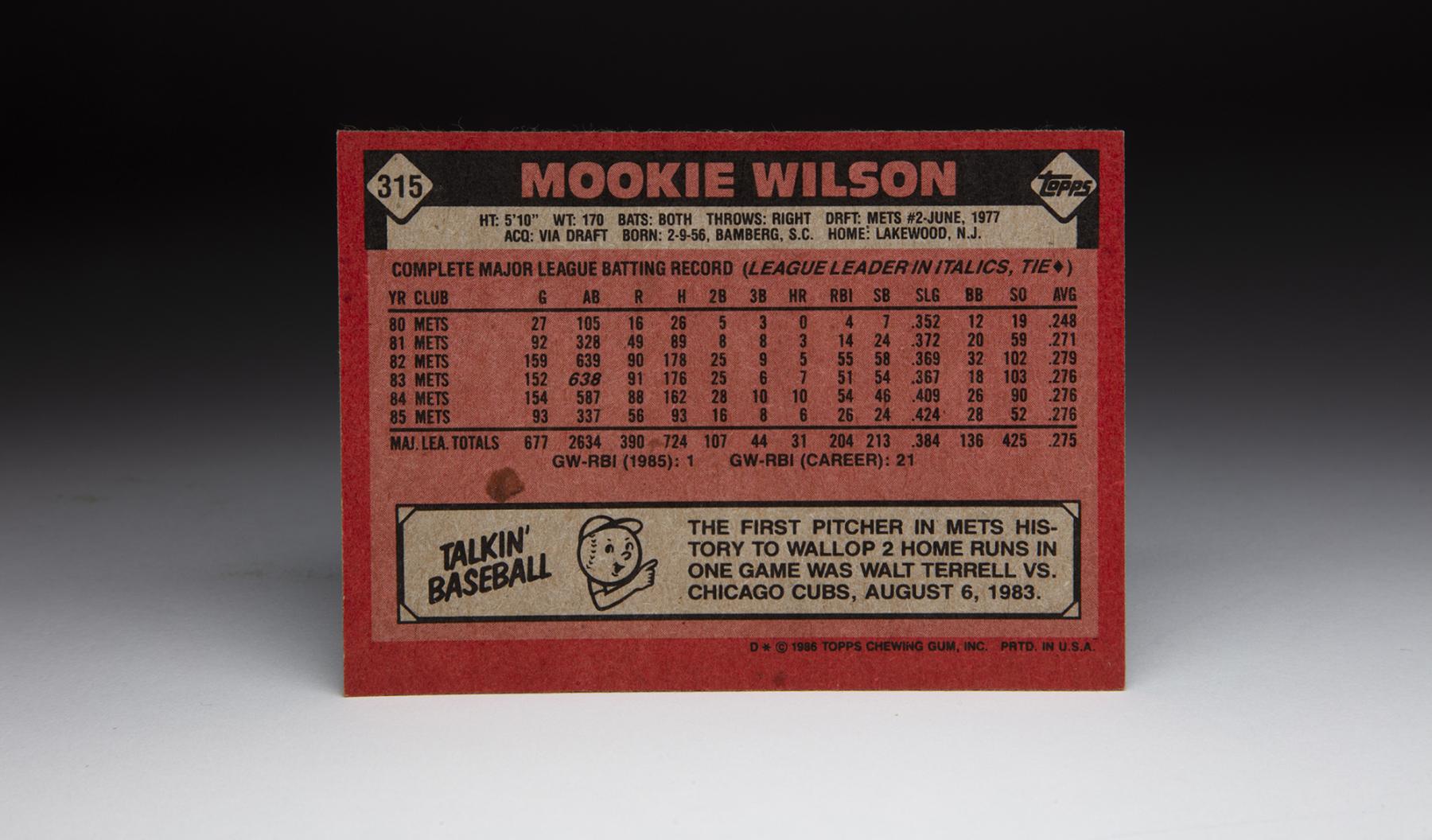

William Hayward Wilson was born Feb. 9, 1956, in Bamberg, S.C. One of 12 children raised on the small farm of James and Nancy Wilson, Mookie – a name his grandmother gave him – starred on the diamond at Bamberg-Ehrhardt High School – the third of seven brothers to play for B-E – helping the Red Raiders win the first of eight straight state championships during his senior year in 1974. Wilson would call Bamberg-Ehrhardt head coach David Horton the most influential coach he ever had.

Though he didn’t try out for the high school team until he was a sophomore, Wilson quickly made an impression on Horton.

“I didn’t know if he could play; he didn’t know either,” Horton told the Charlotte Observer. “He had two left feet and a problem with fly balls.

“You could tell, though, he had athletic ability. You knew it was just a matter of time.”

Mets Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

Following graduation, Wilson committed to play for South Carolina State. But the university unexpectedly dropped the program that year, leaving Wilson to enroll at Spartanburg Methodist College.

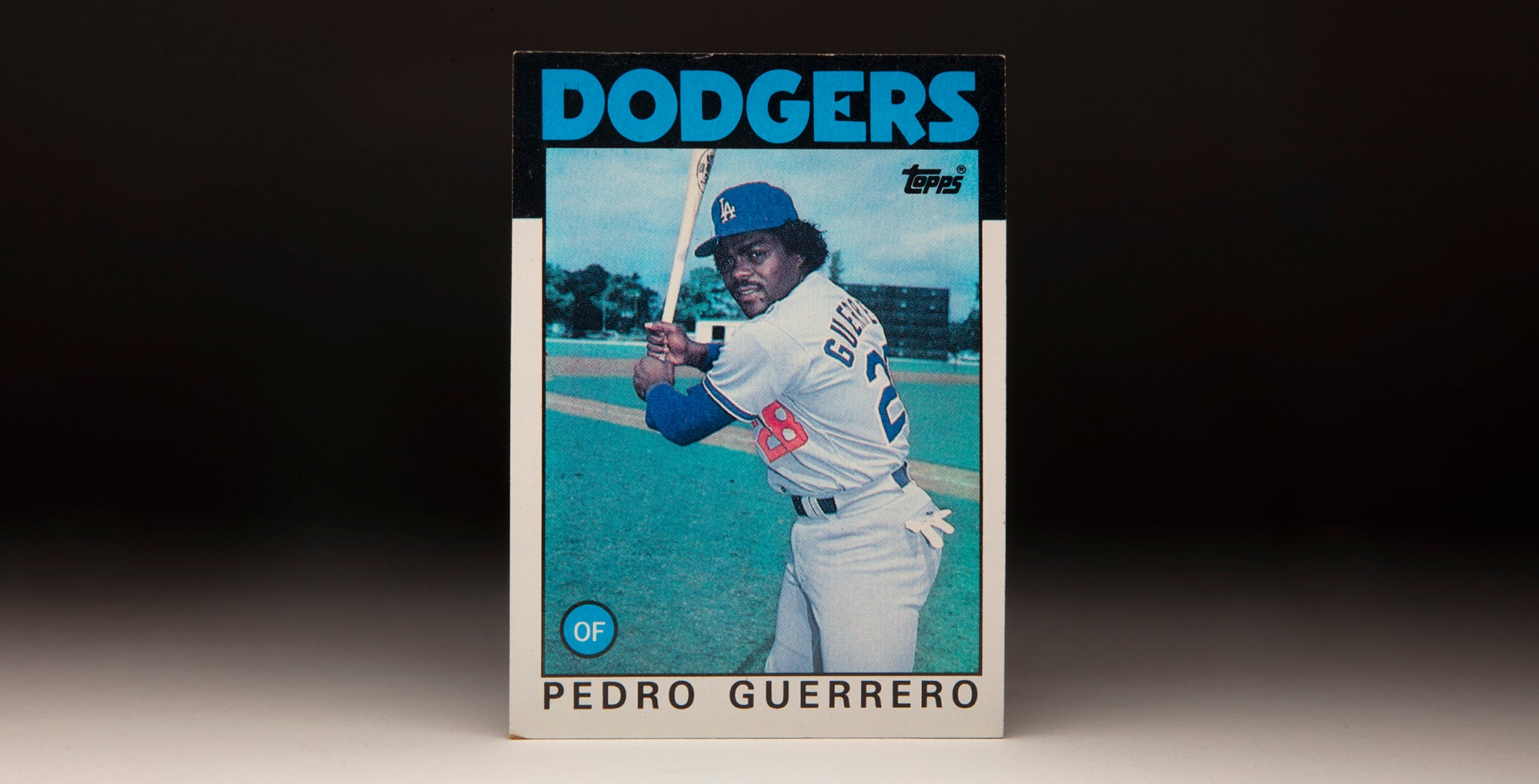

Wilson’s ability drew notice quickly, and the Dodgers selected him in the fourth round of the January 1976 MLB Draft. But Wilson opted to enroll at the University of South Carolina to continue his collegiate career.

In 1977, Wilson helped the Gamecocks advance to the College World Series, finishing second after falling to Arizona State 2-1 in the title game. At 43-12-1, South Carolina totaled the second-most wins in program history.

“That was an amazing year,” Wilson – who led South Carolina with a .357 batting average – told The State in Columbia, S.C. “It reminded me of (the Mets) in 1986. Talent-wise, maybe some teams had more position by position, but we had a bunch of guys who enjoyed playing together.”

In the June 1977 MLB Draft, the Mets selected Wilson in the second round – and Wilson quickly signed and reported to Class A Wausau of the Midwest League, where he hit .290 with 50 runs scored and 23 steals in 68 games.

In 1978, Wilson was promoted to Double-A Jackson of the Texas League, where he hit .292 with 72 runs scored, 72 RBI and 38 steals. But on June 22, Wilson focused on his personal life rather than baseball when he married Rosa Gilbert at home plate of Smith-Wills Stadium prior to a game with Arkansas and in front of 1,147 fans.

Gilbert was escorted to home plate by Jackson Mets general manager Rick Currant, and Wilson and Gilbert exited the field after the ceremony under an arch of bats held high by his teammates.

“I thought he was just kidding when he suggested it,” Gilbert told the Clarion-Ledger in Jackson. “But then I found out he was serious and it was all right with me.”

Gilbert had previously been in a relationship with Mookie’s older brother Richard. That relationship produced a son, Preston, and starting at age 3 Preston began to consider his uncle Mookie as his father.

In time, Preston Wilson would also become a major leaguer.

Wilson debuted with Triple-A Tidewater in 1979 and hit .267 with 49 stolen bases and 84 runs scored in 141 games, earning the International League’s Rookie of the Year Award. Now a top-rated prospect, Wilson performed well in Spring Training in 1980 but was one of the final cuts from the big league team.

“I thought I had made the big club,” Wilson told The State. “I was a little disappointed when they sent me down. But…I decided I would work just that much harder to get back to the big leagues.”

A natural right-handed hitter, Wilson was encouraged by the Mets to adopt switch-hitting in the spring of 1980. The experiment paid off as Wilson hit .295 with 50 stolen bases and 92 runs scored for the Tides that year.

“It’s amazing how well he has made the adjustment,” Tidewater manager Frank Verdi told The State. “In the International League, you have pitchers who are just one step away from the majors or have just come down from here. Mookie is learning to switch-hit against that kind of pitching, which tells you something. This is an exceptional athlete.”

On Sept. 2, the Mets brought Wilson to the majors. In 27 games – 26 of which came in center field – Wilson hit .248 with seven steals and 16 runs scored.

He began the 1981 season as the Mets’ right fielder and leadoff hitter, then moved to center field in May and remained there the rest of the season, hitting .271 with 24 steals in 92 games en route to a seventh-place finish in the NL Rookie of the Year voting.

“You have to be in my position to realize what it’s like to have a chance to be successful in New York,” Wilson told the New York Daily News. “I’m just so happy to be here.”

Wilson was part of the first wave of talented prospects to come through a Mets system that slowly brought the club back into pennant contention. From 1982-84, Wilson put up remarkably consistent numbers in center field, hitting .279, .276 and .276 with 90, 91 and 88 runs scored and 58, 54 and 46 stolen bases. New York won 65 games in 1982 and 68 a year later, then vaulted to 90 victories in 1984 under new manager Davey Johnson.

By the end of the 1983 season, Wilson had totaled 143 stolen bases – the most in Mets history. In January of 1984, Wilson and the Mets agreed to a multi-year contract. And with young stars like Hubie Brooks, Darryl Strawberry, Dwight Gooden and Ron Darling joining Wilson in the lineup, the Mets were poised for greatness.

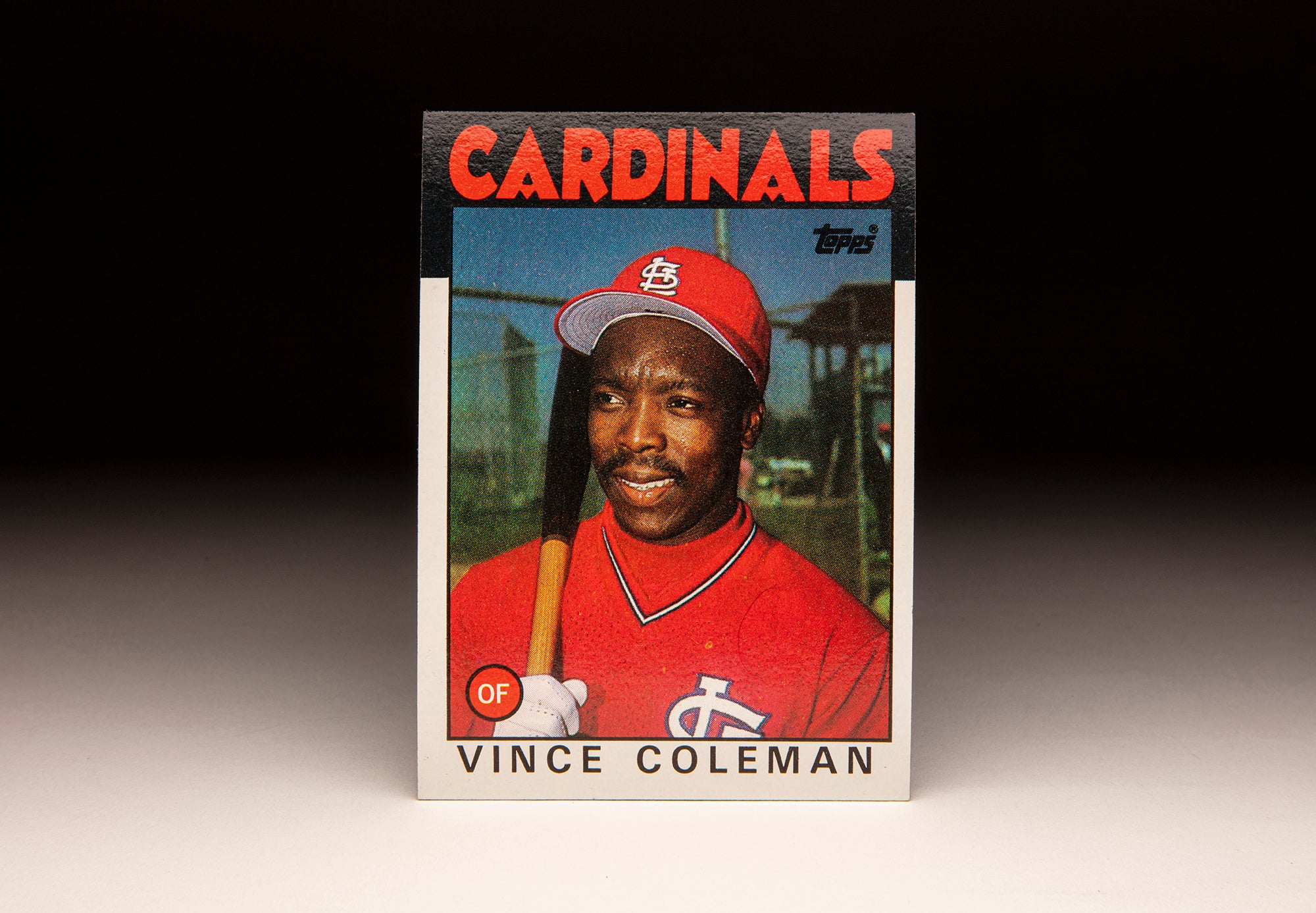

But Wilson suffered a right shoulder injury in April of 1985 that stubbornly refused to heal. After appearing as a late-inning replacement on July 1 against the Pirates, Wilson underwent surgery – he had two procedures on the joint during 1985 – and did not play again until Sept. 1. He finished the season with a .276 batting average, 56 runs scored and 24 steals in 93 games for a Mets team that won 98 games but finished three back of the Cardinals in the NL East.

A healthy Wilson could have been the difference.

Then in Spring Training, the optimism surrounding Wilson and the Mets took a hit when Wilson was struck above the right eye by a ball thrown by shortstop Rafael Santana during a rundown drill. Wilson did not appear in a game until May 9 – by which time Lenny Dykstra had established himself as a legitimate force in center field.

By then, the Mets were 18-4 and on a roll.

“I’m happy for the Mets that it’s going so well, but it will probably be a little uneasy for me until I have a little success of my own,” Wilson told Newsday. “I realize I have some catching up to do and as long as the team sees it that way, I don’t see my return as a disruption.”

Wilson and Dykstra shared the centerfield duties for much of the summer before left fielder George Foster was released in August. Wilson saw most of his playing time in left field after that point, finishing the season with a .289 batting average and 25 steals in 123 games as New York rolled to 108 wins and the NL East title.

“I’ve handled everything, but not as easily as people think,” Wilson told the Hartford Courant. “The hardest thing for me to be is a part-time player. I hate watching baseball. I just hate it.”

Appearing in his first Postseason games in the NLCS vs. the Astros, Wilson hit just .115 but helped key the Mets’ ninth-inning rally in Game 6 when he singled home Dykstra to cut the Astros lead to 3-1. Wilson later scored on a double by Keith Hernandez and the Mets eventually tied the game, forcing extra innings.

When the Mets won the game in the 16th inning, Wilson and his teammates were headed to the World Series.

“Never in my life,” Wilson told the Asbury Park Press, “have I seen or read about anything like this game.”

But more improbable drama was on the horizon.

Wilson totaled just one hit in the first three games of the World Series against the Red Sox, but had two hits apiece in Games 4 and 5. But Boston held a 3-games-to-2 lead heading into Game 6 at Shea Stadium. And when the Red Sox scored two runs in the top of the 10th inning to take a 5-3 advantage, Boston stood just three outs away from its first World Series win since 1918.

But after reliever Calvin Schiraldi got two quick outs, Gary Carter singled and moved to second on a single by Kevin Mitchell. Ray Knight then fought off an inside pitch and looped a single into center, scoring Carter and bringing reliever Bob Stanley into the game to face Wilson.

Stanley eventually threw a wild pitch, and Wilson frenetically waved Mitchell home from third base with the tying run. One pitch later, Wilson chopped a low and outside pitch down the first base line.

Buckner, who was usually removed for defensive purposes in similar situations, saw the ball slither under his glove – allowing Knight to score from second base with the winning run.

Wilson may have beaten Buckner to the bag even if the Red Sox first baseman had fielded it cleanly. But the error allowed the run to score and sent most of the 55,078 fans into delirium.

“Nothing surprises me about this club,” Wilson told the Associated Press. “We just do not give up.”

In Game 7, Wilson and the Mets found themselves trailing 3-0 heading into the bottom of the sixth. But Wilson helped key a three-run rally with a single, scoring the second run of the inning. The Mets scored three more in the seventh and two in the eighth to win 8-5 and clinch the title.

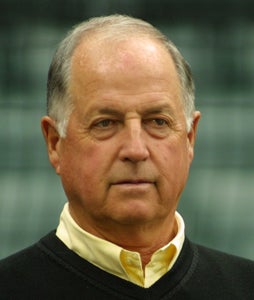

With the Mets looking to build a dynasty, general manager Frank Cashen acquired young star Kevin McReynolds from the Padres on Dec. 11, 1986, in exchange for five prospects, including Mitchell. A center fielder in San Diego, McReynolds was moved to left field in New York, setting up a logjam in center with Dykstra and Wilson.

Wilson asked to be traded throughout the 1987 season but Cashen would not budge, leaving Wilson to play in 124 games while hitting .299 with 21 steals. But the Mets fell to 92-70 and finished second in the NL East.

New York bounced back with 100 wins in 1988 and finished first in the division, with Wilson and Dykstra again sharing work in center field. Wilson hit .296 in 112 games but batted just .154 in four games in the NLCS as the Dodgers knocked the Mets out of the Postseason.

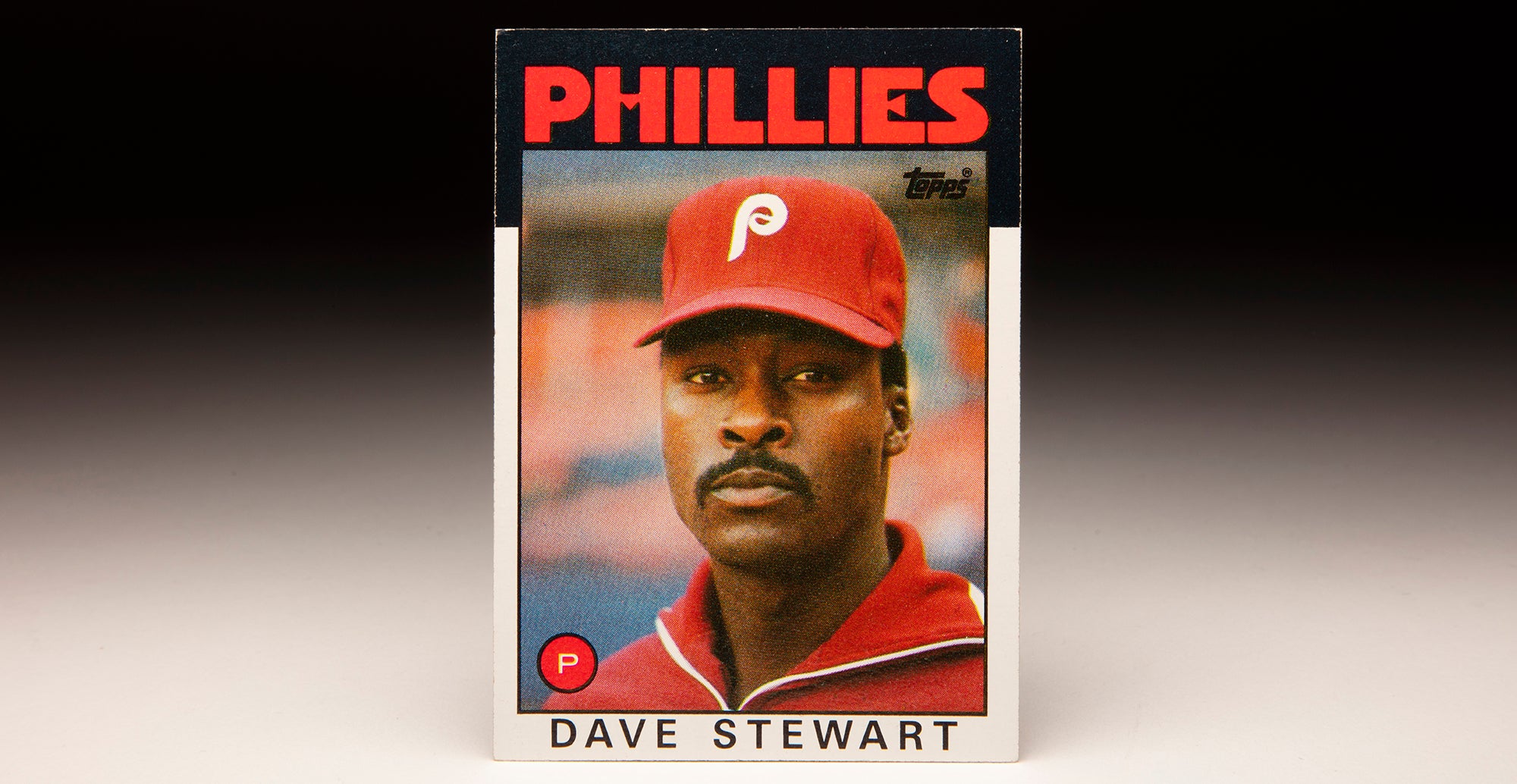

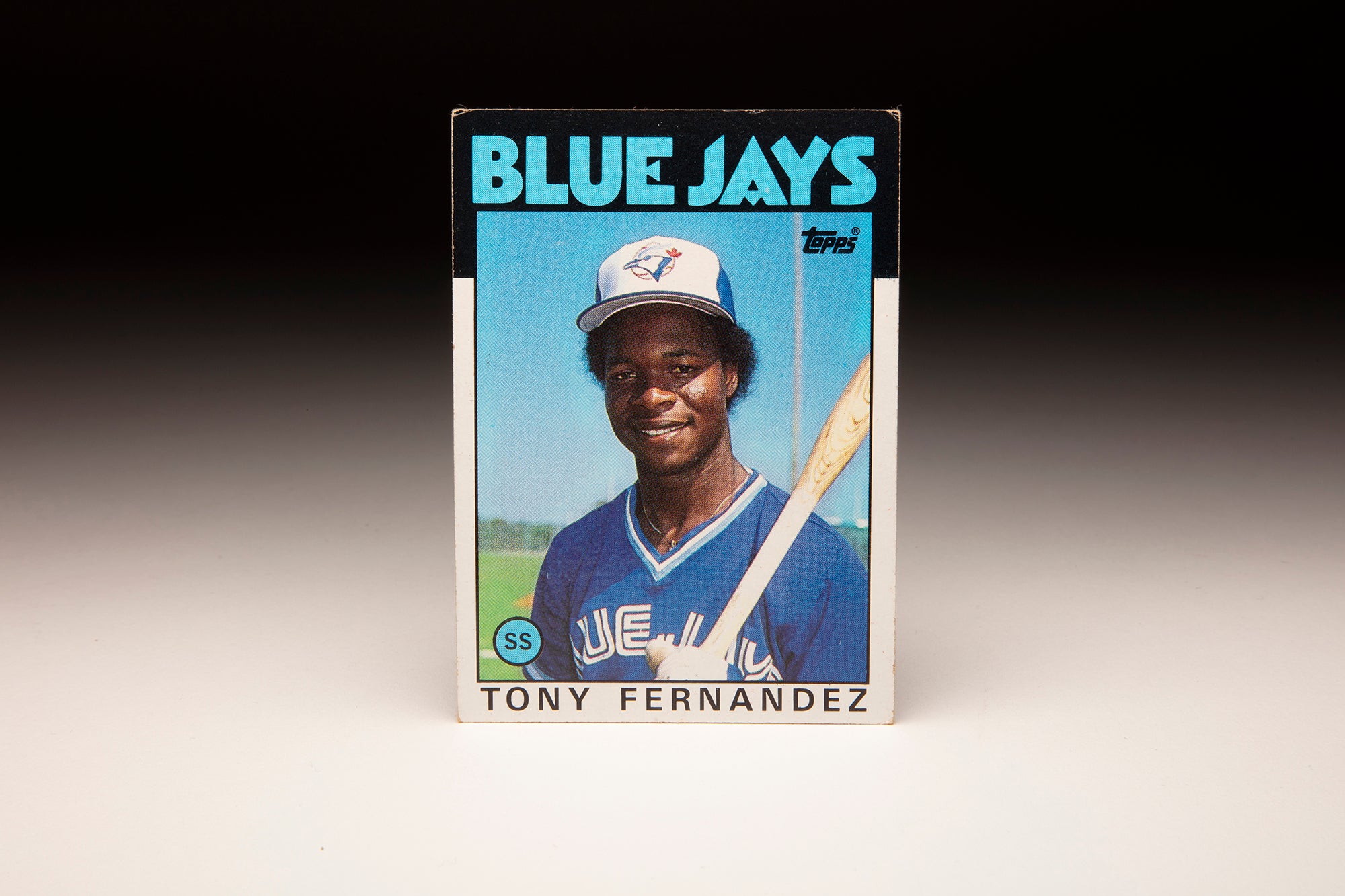

The 1989 season marked the final year of Wilson’s multi-year deal, but Wilson was not in New York at the end of the season. With the Mets hovering around the .500 mark for most of the first few months of the campaign, Cashen traded Dykstra to the Phillies for Juan Samuel on June 18, then shipped Wilson to the Blue Jays on July 31 in exchange for pitcher Jeff Musselman and a minor leaguer.

Wilson provided an immediate spark for the Blue Jays, hitting .298 in 54 games while helping Toronto win the AL East. The Blue Jays lost to Oakland in the ALCS – with Wilson hitting .263 with two runs scored and two RBI – but his play during the regular season earned him a vote in the American League MVP balloting despite his short two-month tour in the AL.

Wilson became a free agent after the season but quickly signed a two-year, $3 million deal – with a team option for a third season – to return to Toronto.

“He was only here for two months, but we probably wouldn’t have been in the playoffs if it hadn’t been for Mookie Wilson,” Blue Jays general manager Pat Gillick told the Canadian Press.

Wilson played in 147 games in 1990 as the Blue Jays regular center fielder, hitting .265 with a career-high 36 doubles, 81 runs scored and 23 steals. But Toronto fell to second place in the AL East, prompting Gillick to acquire center fielder Devon White from the Angels in a trade.

Once again relegated to a bench role, Wilson hit .241 in 86 games as Toronto returned to the Postseason as AL East champions. Wilson had two hits in three games in the ALCS as Minnesota defeated the Blue Jays.

When Toronto declined to pick up Wilson’s option for 1992, Wilson’s big league career came to an end.

He returned to the Mets as first base coach from 1997-2002 and then managed in the minor leagues until 2005, then coached for the team again in 2011. While out of baseball, Wilson kept busy driving big rig trucks, having earned his commercial driver’s license in 1999.

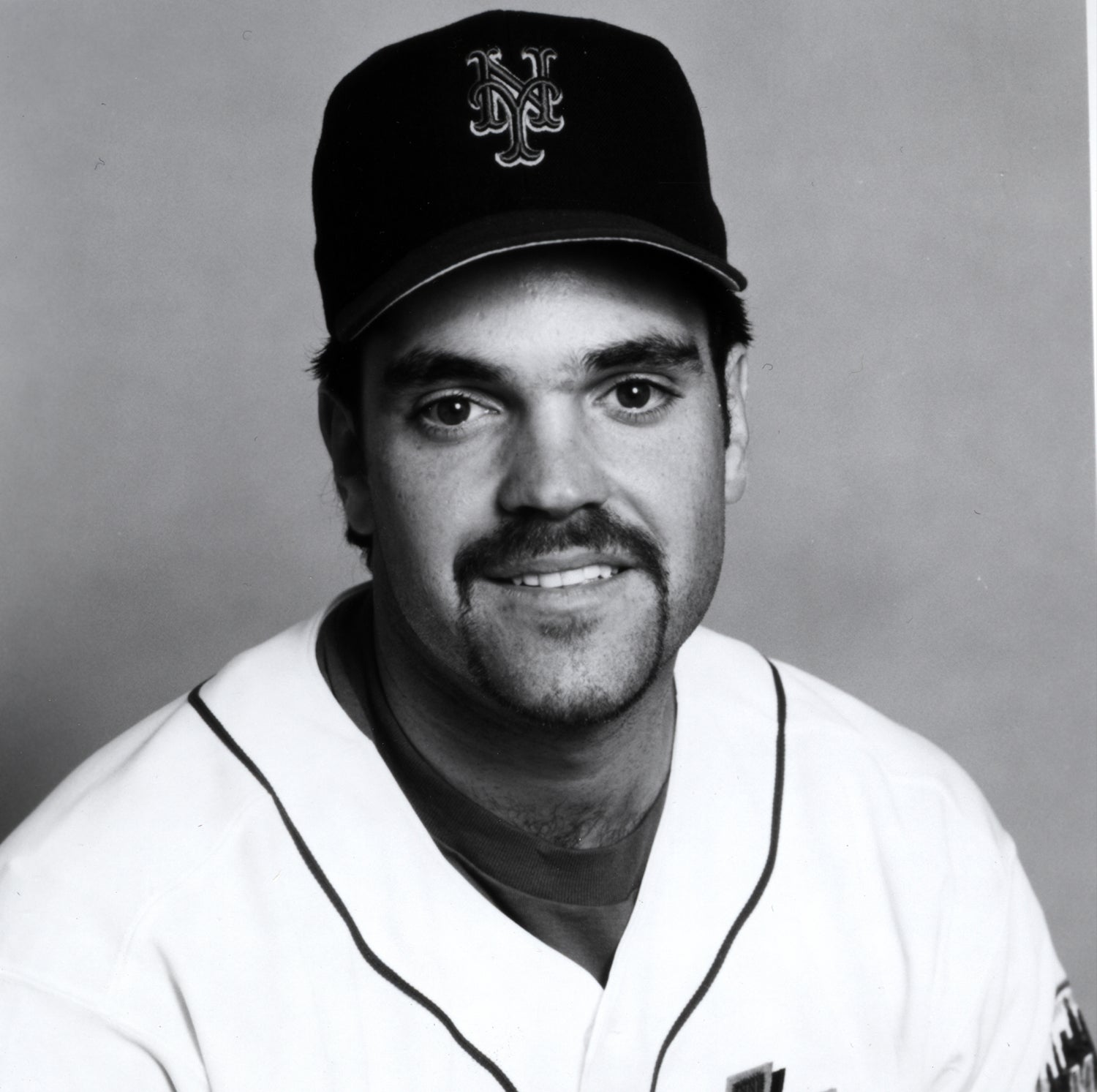

Meanwhile, Preston Wilson was selected by the Mets with the ninth overall pick in the 1992 MLB Draft, having starred at Bamberg-Ehrhardt High School just like his stepfather. Preston hit seven grand slams for Bamberg-Ehrhardt in 1992, setting a single-season high school record.

“At this stage, without question, he’s a better player than I was,” Mookie told the Charlotte Observer days before Preston picked by the Mets.

Preston debuted in the big leagues on May 7, 1998, then was traded to the Marlins eight days later in the Mike Piazza deal. Preston finished second in the NL Rookie of the Year voting in 1999 and later played for the Rockies, Nationals, Astros and Cardinals – earning an All-Star Game selection in 2003 and a World Series ring with St. Louis in 2006.

For the Wilson family, it marked the completion of a circle that began on an unforgettable night in 1986 at Shea Stadium.

“They are the loosest bunch of guys I ever saw,” Wilson told the Associated Press about the 1986 Mets. “People call it arrogance. I call it amazing.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum