- Home

- Our Stories

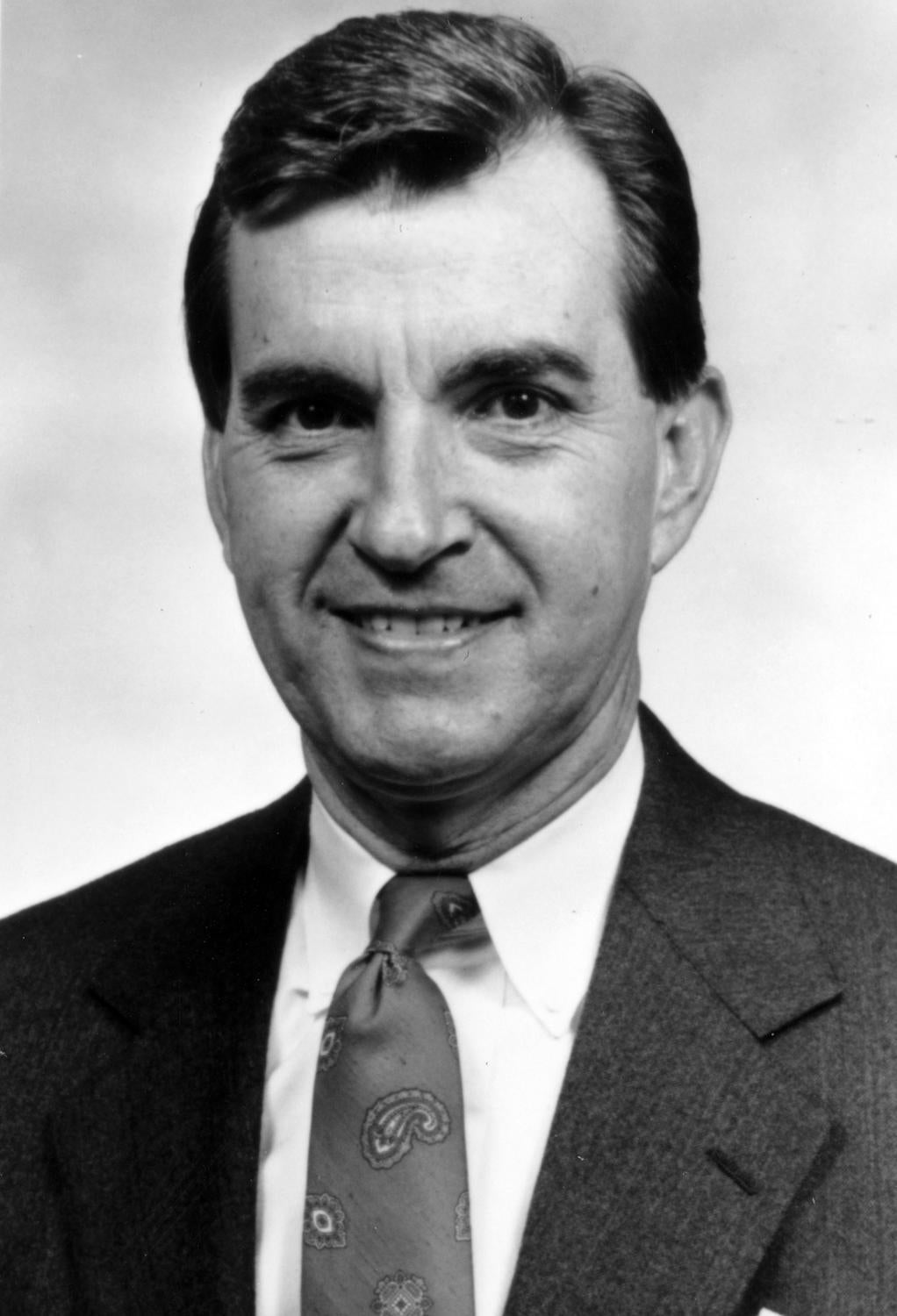

- #CardCorner: 1988 Topps Don Slaught

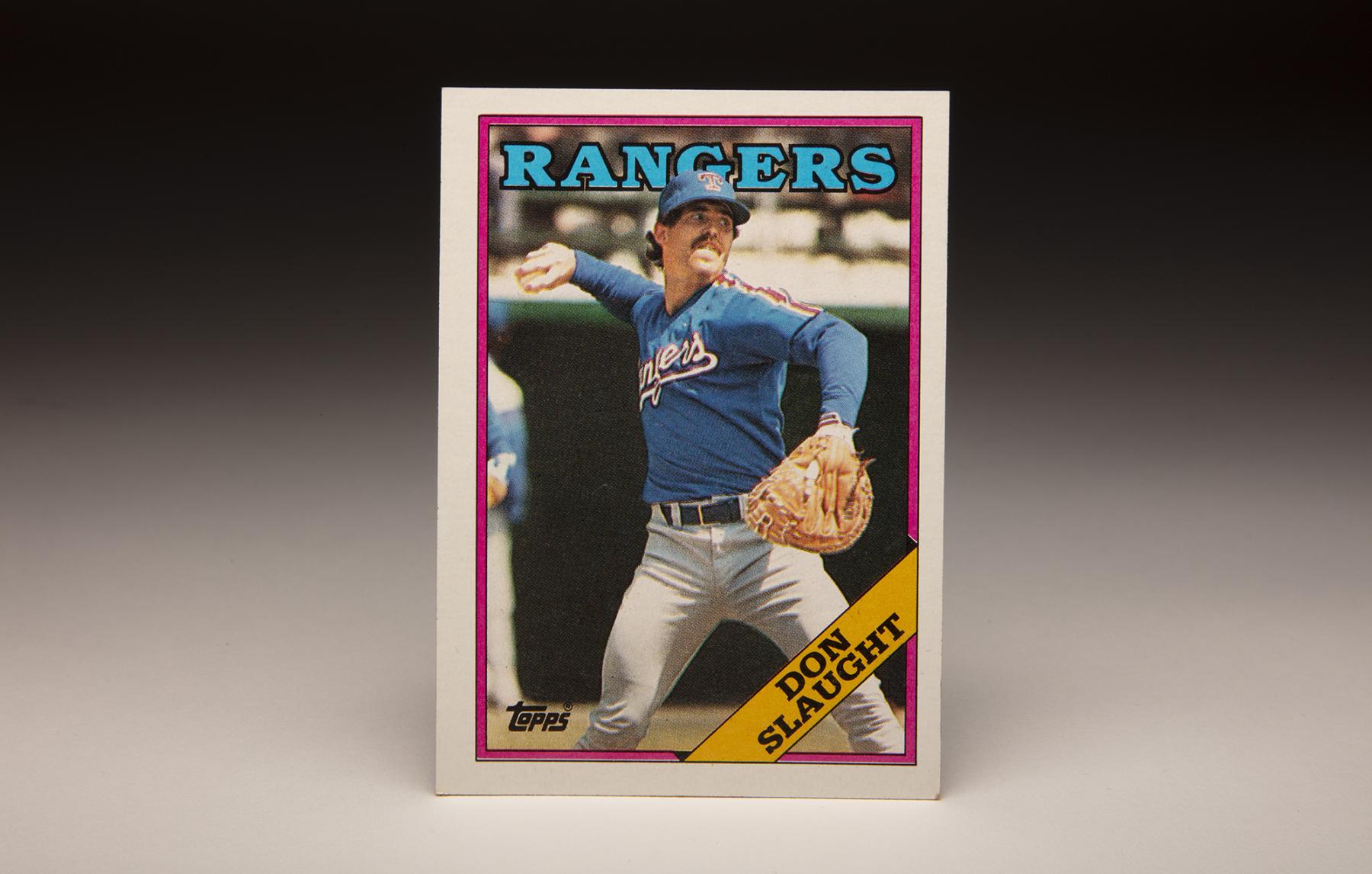

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Don Slaught

The picture of Texas Rangers catcher Don Slaught crumpled on the Fenway Park dirt ran in newspapers around the country on May 18, 1986. Slaught was hit in the face by a pitch from Boston’s Oil Can Boyd, and for many – including Slaught – it instantly brought back memories of another beaning 19 years earlier on the same field.

“Tony Conigliaro is the only thing that went through my mind,” Slaught told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram after the game.

The fact that Slaught was able to speak at all portended well, however, for his future. And by the end of the season, Slaught had returned to being one of the best hitting catchers of his era.

Born Sept. 11, 1958, in Long Beach, Calif., Slaught was an all-around athlete in high school but went undrafted and was not highly recruited by colleges. He was nearly cut at UCLA prior to his freshman season, then left school to enroll at El Camino College in Torrance, Calif., before returning to UCLA for his final two seasons where he thrived on the field and in the classroom, earning academic All-American status as an economics major.

“I made the team as a freshman because I worked so hard, stealing bases and running sprints,” Slaught told the Kansas City Times. “They kept me because they liked the way I played.”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

An all-PAC-10 pick at UCLA in 1979 when he hit better than .400, Slaught was selected in the 20th round of the 1979 MLB Draft by the Brewers but returned to UCLA, where he again won all-league honors in 1980. That year, Slaught was drafted in the seventh round by the Royals.

Assigned to Class A Fort Myers of the Florida State League, Slaught hit .261 in 50 games and began the 1981 season with Double-A Jacksonville. He hit .335 with a .391 on-base percentage for the Suns, earning a mid-season promotion to Triple-A Omaha. But in August, Slaught suffered a broken left leg when he collided with Denver’s Wallace Johnson – who was wearing a heavy knee brace that impacted Slaught’s shin – while blocking the plate. The injury cost him a month of playing time but he accelerated his recovery in the offseason by working out at a local dance studio near his California home.

By this time, Slaught was considered one of the top catching prospects in the game.

“He’s got every attribute you’d look for in a catcher,” Royals general manager John Schuerholz told the Kansas City Times in 1982. “He’s a quarterback-type…knows the game situation, knows the pitcher on the mound, knows the hitter. We think he’s our answer.”

Slaught earned an invitation to Spring Training with the Royals in 1982 but was optioned to Triple-A to start the season.

“He’s going to be our No. 1 catcher someday,” Royals manager Dick Howser told the News-Press in Fort Myers, Fla., “this year, next year, the following year – I can’t predict. But if he sits around, that won’t help him. I don’t look at him as a backup catcher.”

Slaught debuted in the big leagues on July 6, 1982, the day after Royals catcher John Wathan fouled a ball off his left ankle, fracturing the bone. Slaught was hitting .273 at Triple-A Omaha when he was called up to the majors and hit .278 in 43 games with the Royals to finish the 1982 season.

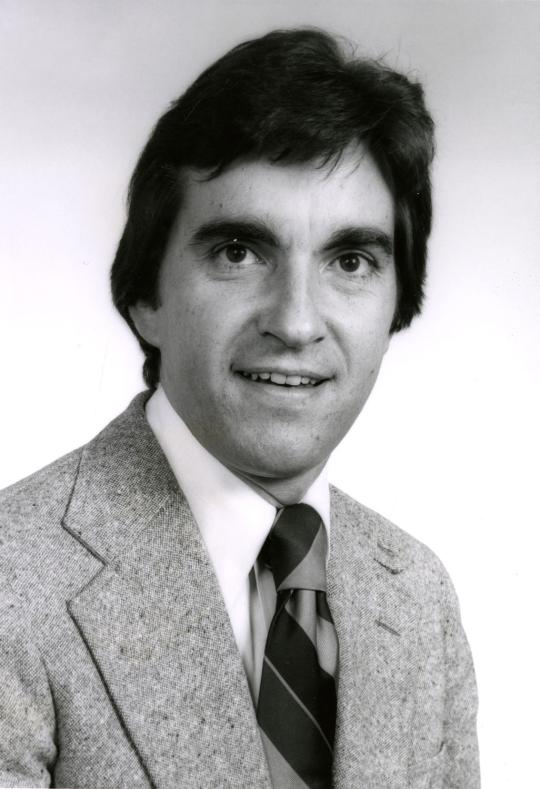

Prior to the 1983 season, Slaught – in a move decades ahead of its time – applied statistical analysis to college athletes in an attempt to determine why certain players make it to the big leagues while others do not. In one analysis, Slaught determined that Babe Ruth’s 1921 season – where Ruth hit 59 home runs – was the greatest season in baseball history.

Modern analysis suggests Slaught’s methods were accurate: Among all position players for seasons after 1900, Ruth and his 1921 season rank third all-time in Wins Above Replacement at 12.6, trailing only Ruth in 1927 (fractionally higher at 12.6) and Ruth in 1923 (14.2).

“If I understand the game better or learn little things that improve the way I play,” Slaught told the Associated Press, “so much the better.”

Slaught was ticketed to share time with Wathan – who set a record for catchers with 36 steals in 1982 despite his ankle injury – in 1983.

And though Wathan got the bulk of the playing time, Slaught hit .312 in 83 games, confirming that he was the catcher of the future for the Royals.

“I like to go out there and get dirty,” Slaught told the News-Press. “I’ve always been that way. I think a catcher has to be scrappy, he has to do things to win.”

In 1984, Wathan and Slaught effectively switched roles, with the 34-year-old Wathan appearing in 97 games while Slaught played in 124 (123 behind the plate) while hitting .264 and helping the Royals win the American League West title. Slaught was hitting .179 as late as June 18 but Howser stuck with him – and was rewarded when Slaught hit .296 with 34 RBI over his final 88 games.

His work with young Royals pitchers like Bud Black, Mark Gubizca and Bret Saberhagen helped the upstart Royals hold off the Angels and Twins for the division title.

“What I had to do this year is help the pitchers with the batters,” Slaught told the News-Press. “They really haven’t had that much experience with the hitters up here.”

Slaught went 4-for-11 (.364) in the ALCS vs. the Tigers, but Detroit won the series in three games.

Then on Jan. 18, 1985, the Royals – seeking even more experience at catcher for their young staff – executed a four-team trade with the Rangers, Brewers and Mets that sent Slaught to Texas and brought veteran receiver Jim Sundberg to Kansas City.

“They have a young pitching staff and having a guy (Sundberg) who has caught 1,200 games, a guy with that kind of experience, could only help,” Slaught told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram following the trade.

Slaught hit .280 in 1985 with eight homers and 35 RBI while finishing second in the AL in passed balls with 13 – a result of multiple starting assignments with knuckleballer Charlie Hough on the mound. The Rangers finished 62-99 and in seventh place in the AL West while the Royals went on to win the World Series behind their young aces.

On May 17, 1986, Slaught was hit in face by Boyd, breaking his nose and left cheekbone. Slaught was hitting .293 at the time of the injury and missed the next seven weeks, returning July 4. A metal plate was placed in his face, and for a time, Slaught wore a football-like mask at the plate. He was left with no feeling in parts of his face.

Slaught said he never saw the pitch, which blended into the white shirts worn by fans in the Fenway Park bleachers. He hit .252 in the final 65 games of the season, regularly fielding questions about his ability to overcome the physical and mental challenges of such an injury.

“These bones, even though they have healed, are never going to be as strong,” Slaught told the Kansas City Times. “People who see (the replay of the injury) think it’s a gory picture. They don’t know I’m all right.”

Slaught finished the 1986 campaign with a career-high 13 home runs and 46 RBI while hitting .264. But in 1987, Slaught slumped to .224 in 95 games and lost playing time to prospect Mike Stanley. On Nov. 2, 1987, the Rangers traded Slaught to the Yankees for a player to be named later that turned out to be pitcher Brad Arnsberg.

“Texas was a great place to play, but I wasn’t playing,” Slaught told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram after the trade. “It was a good opportunity when I came here.”

Slaught joined the Yankees amidst a catcher logjam, with Rick Cerone and Joel Skinner also vying for playing time. But Cerone was released on the eve of the 1988 season, and Slaught got the bulk of the playing time that year – hitting .283 with nine homers and 43 RBI despite missing a month with a groin injury.

Slaught never doubted he would eventually win the starting job.

“I think when we leave camp that’s the way they’ll look at me,” Slaught told the Record of Hackensack N.J., in Spring Training. “I was hoping for a trade, and this is probably the best place I could go.”

Following the season, the Yankees signed Slaught – who could have become a free agent – to a two-year deal worth $1.3 million. But after Slaught hit .251 in 117 games in the first year of the deal, the Yankees traded him to the Pirates for pitcher Jeff Robinson and prospect Willie Smith on Dec. 4, 1989.

“I’m happy about going to Pittsburgh,” Slaught told the Daily Breeze in Torrance, Calif., prior to the 1990 season. “It will be a challenge to get to know the new hitters and pitchers.”

At 31, Slaught still saw himself as a starting catcher. But with the Pirates, he teamed with lefty-hitting Mike LaValliere to form one of the best platoons in baseball.

In 1990, Slaught hit .300 in 84 games, helping the Pirates win the National League East. It would be the first of three straight division titles for the Pirates, but in each season Pittsburgh would fall in hotly contested NLCS play.

Slaught went just 1-for-11 in Pittsburgh’s six-game loss to Cincinnati in the 1990 NLCS – but bounced back in 1991 to produce a virtual duplicate of his 1990 season, hitting .295 with the same total of RBI (29). He signed a three-year, $3.3 million deal heading into the 1991 campaign.

The Pirates, however, lost the 1991 NLCS to the Braves in seven games, with Slaught hitting .235 in six contests.

Then in 1992, Slaught hit a career-best .345 in 87 games as the Pirates again advanced to the postseason. Once again, Pittsburgh lost to the Braves in seven games – with Slaught hitting .333 with five RBI in five games.

On April 11, 1993, the Pirates released LaValliere after he appeared in just one game that season. Suddenly, Slaught was the unquestioned starter.

“I’ve never thought of it (hitting against right-handers) as being a problem,” said Slaught, who hit .395 against righties in 1992, to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “I look forward to the opportunity. I look forward to playing more.”

At 34, Slaught played as much as he ever had in 1993 – and set career highs in hits (113) and RBI (55) while batting .300 despite leg injuries that limited him to just 13 games in September. But the Pirates finished 75-87, beginning a 20-year stretch where the team would finish each season below .500.

Slaught signed a two-year, $3.2 million extension during the 1993 campaign that would keep him in Pittsburgh through 1995. He hit .288 with a .382 on-base percentage in 76 games in the strike-shortened 1994 campaign.

“If anybody’s earned (a new contract), he has,” Pirates manager Jim Leyland told the Associated Press. “I’m elated he’s back for two more years.”

But shoulder and hamstring injuries limited Slaught to just 35 games in 1995, though Slaught hit his customary .304. In six seasons in Pittsburgh – his ages 31 through 36 seasons – Slaught batted .305 with a .370 on base percentage.

He signed with the Reds as a free agent prior to the 1996 season but found himself with the Angels in Spring Training when his contract was sold at the end of February. He hit .324 in 62 games with California before being traded to the White Sox on Aug. 31, helping Chicago down the stretch run that saw the team finish in second place in the AL Central.

He returned to the National League in 1997 with the Padres, but drew his release on May 27 after going 0-for-20 to start the season. He would not play in the big leagues again.

Slaught soon founded a company called RightView Pro that provided instructional hitting videos and then served as the Detroit Tigers’ hitting coach in 2006, working under Leyland as the Tigers won the American League pennant while scoring 822 runs.

But one week after the Tigers lost to the Cardinals in the World Series, Slaught resigned.

“It wasn’t an easy decision, but it was the right one,” Slaught told the Detroit Free Press. “I knew that when I told (his children) and saw their reactions – especially the younger ones. If I miss these years, I can’t get them back.”

Over his 16-year playing career, Slaught hit .283 with 1,151 hits and 235 doubles. Among all catchers with at least 1,000 games behind the plate, Slaught is one of just 25 with a career batting average of at least .280.

Mighty select company, even if the ever-modest Slaught didn’t acknowledge it.

“What makes me a good catcher is I don’t feel I have any weak points,” Slaught said. “I’m average right down the line, whether it’s throwing or hitting.”

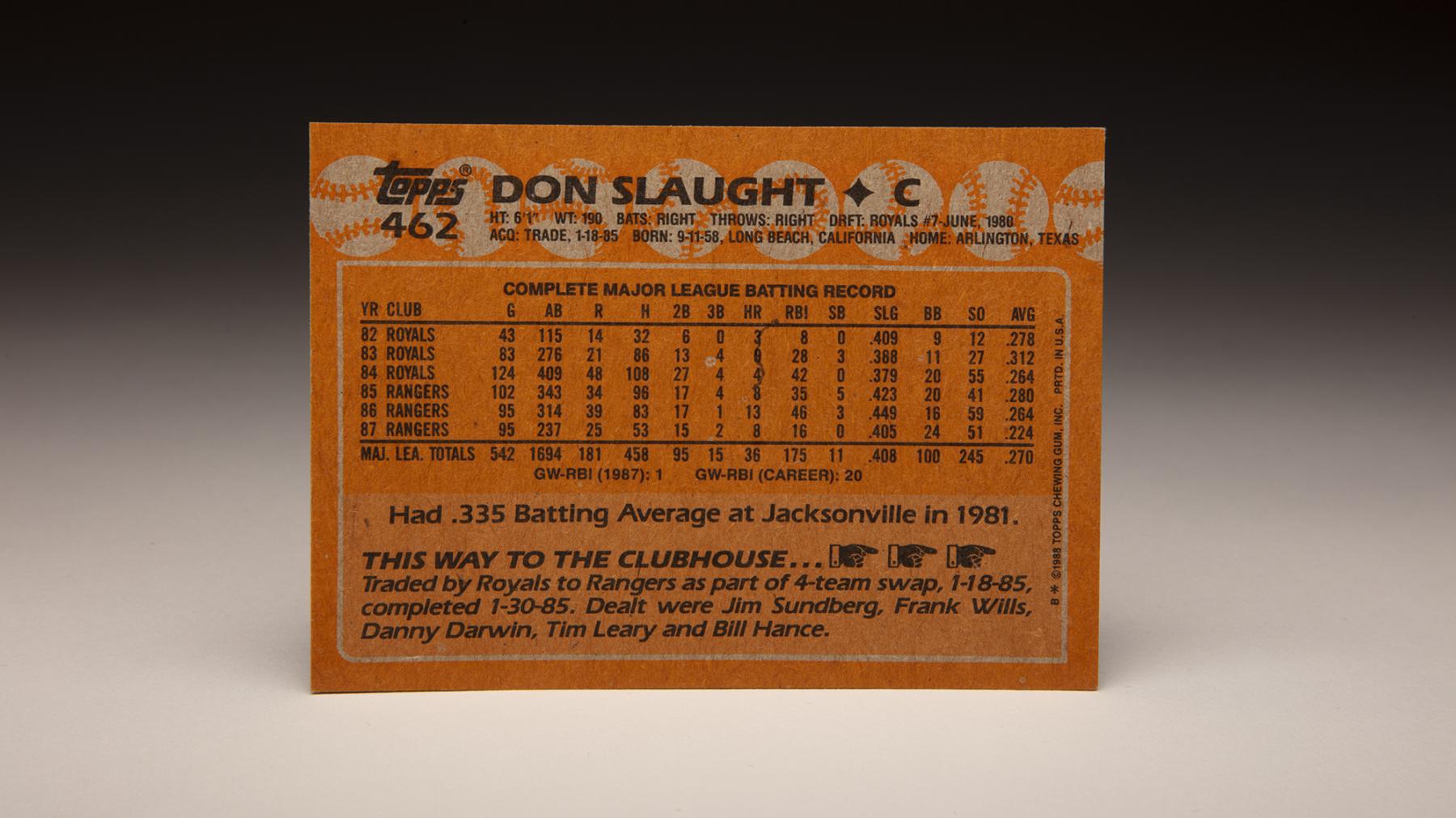

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum