- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1992 Upper Deck Brian Downing

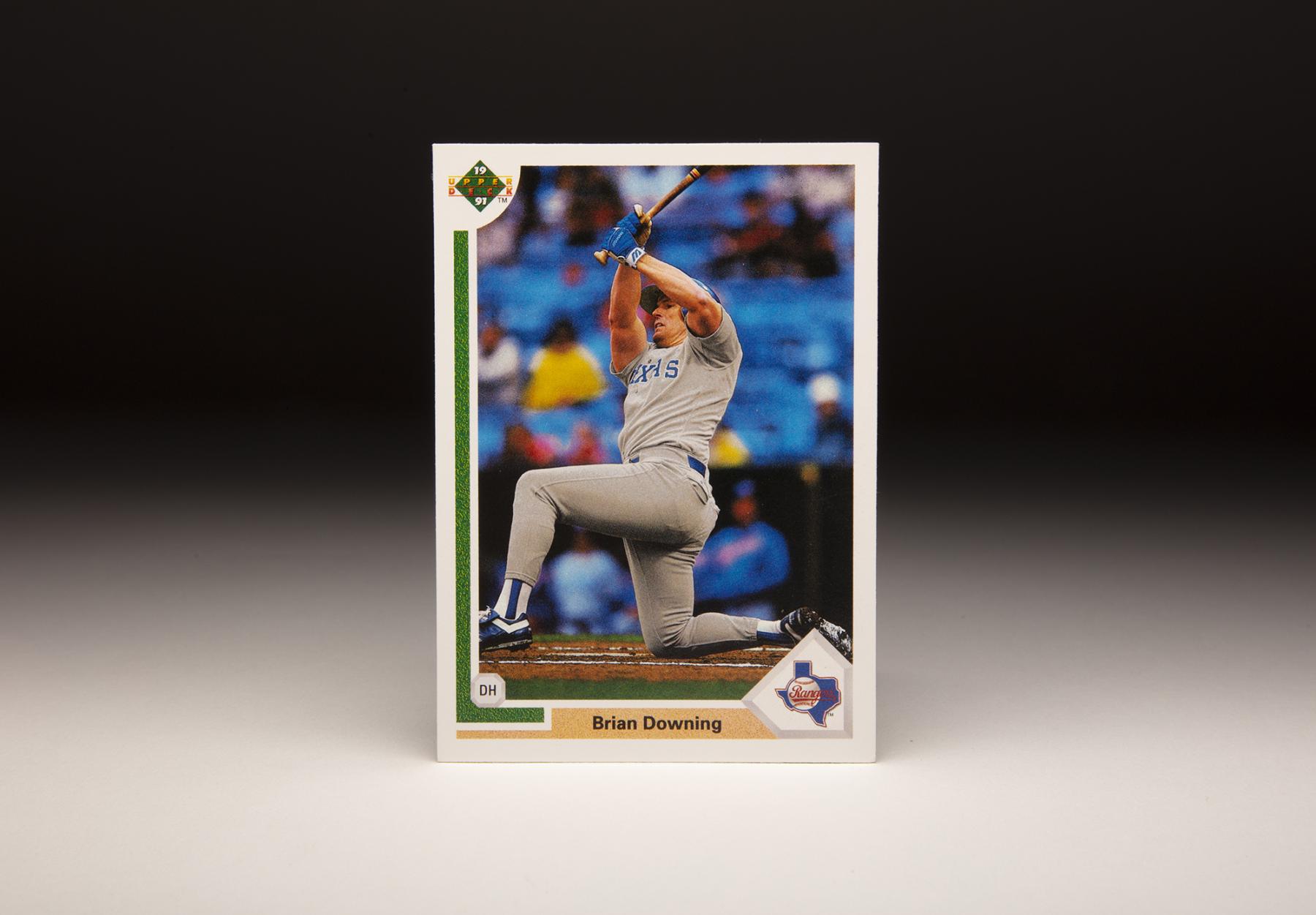

#CardCorner: 1992 Upper Deck Brian Downing

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Over the years, there have been so many cards depicting hitters in the midst of an at-bat that we’ve become accustomed to seeing some attempting to check their swings, or trying to lay down a bunt, or even breaking their bats against a high-powered fastball.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

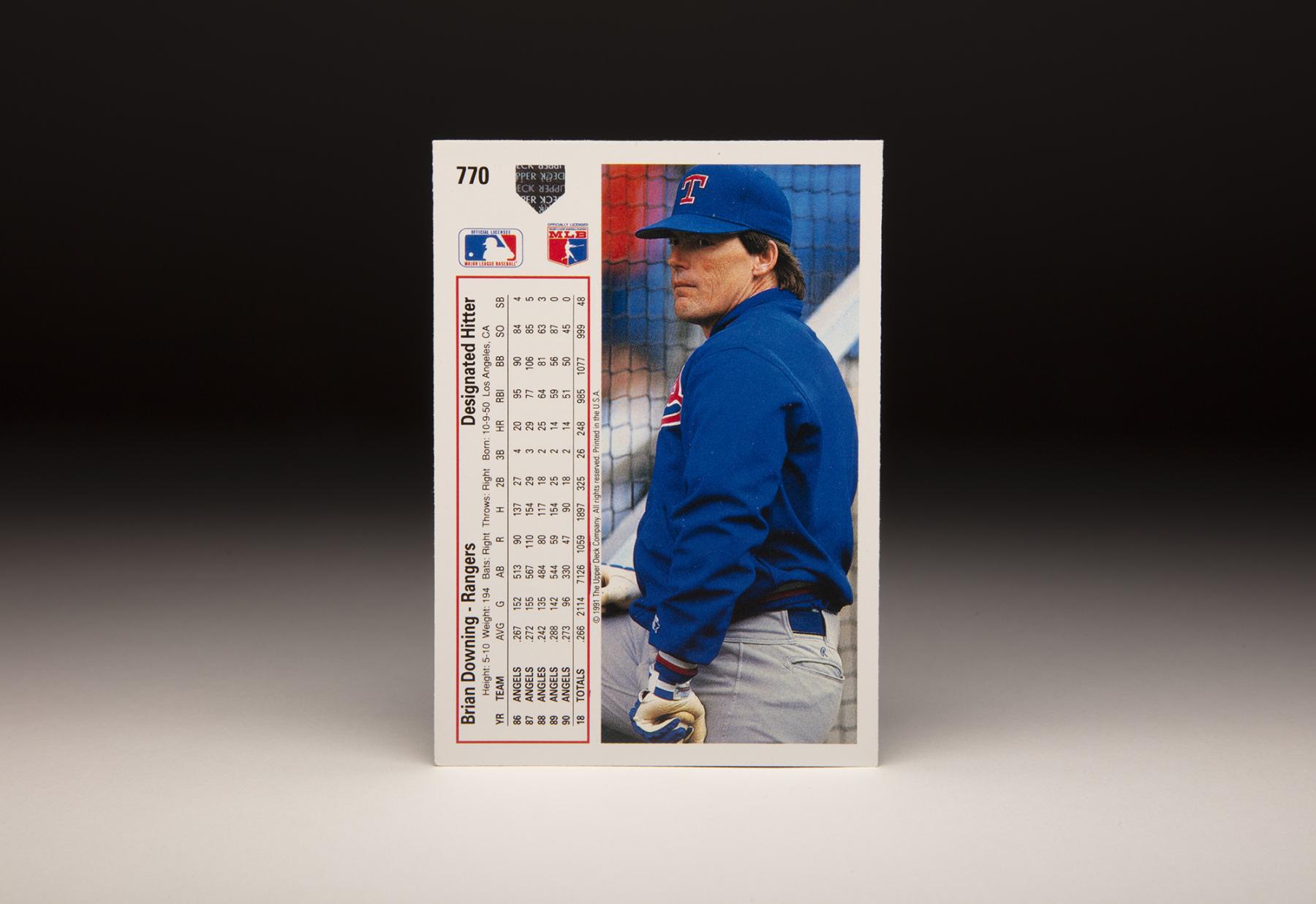

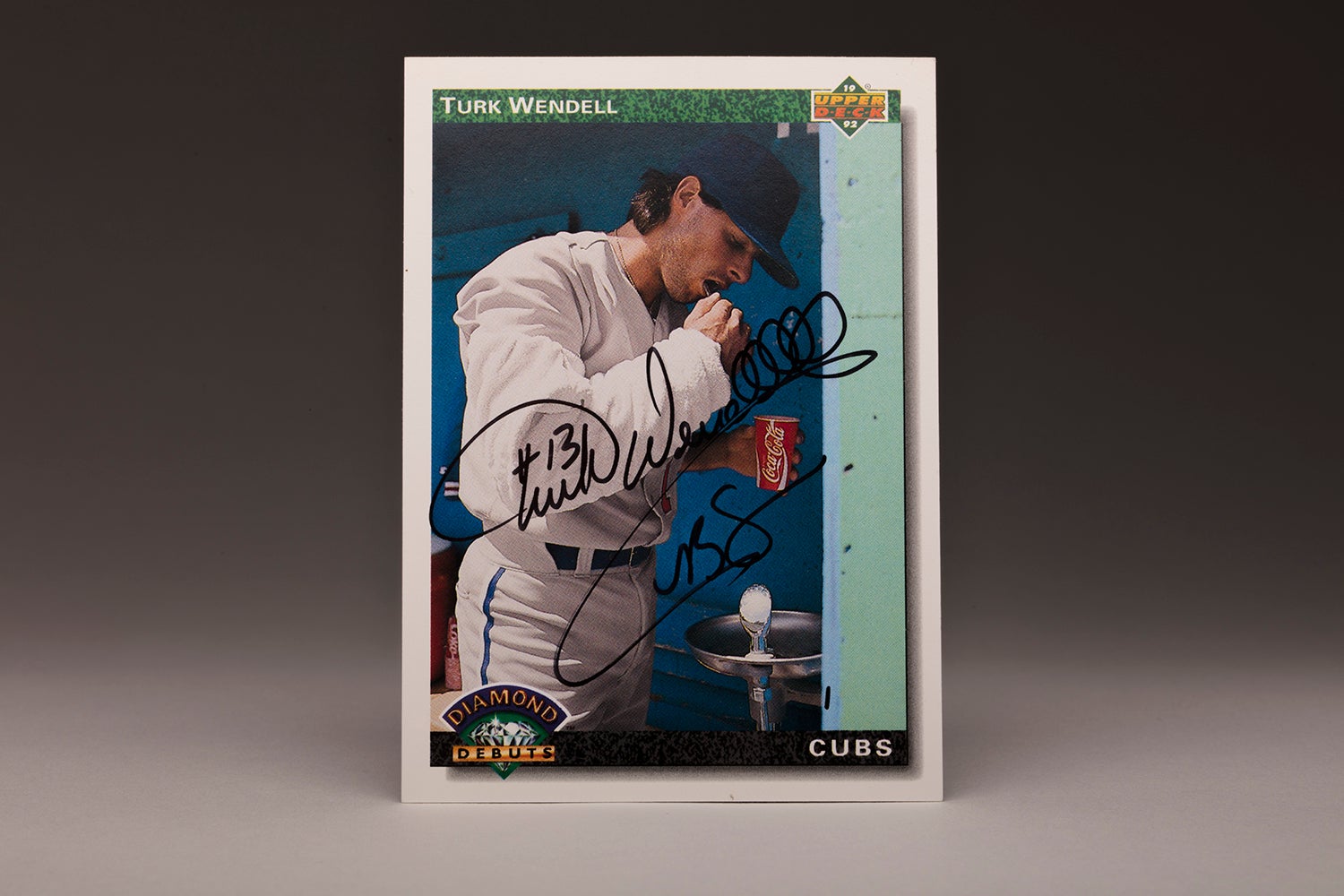

Then there is Brian Downing’s 1992 Upper Deck card. I’m not sure exactly what Downing is trying to do here. Is he attempting to check his swing? If so, why does his bat appear to be in an upper-cut position, rather than on a flatter plane, which is where most check swings end up?

Additionally, Downing has completed his swing with his lower body in an odd position. He has gone down to one knee, while his front leg is bent at a 90-degree angle, with his left foot lifted slightly off the ground. Downing also has an expression of anguish on his face. Clearly, this was not the intended result of his swing. We are left to wonder whether he actually did check his swing, or awkwardly made contact on a weak grounder or pop-up. In a weird way, it seems like appropriately bad batting form for a player who once seemed to have no chance of playing in the major leagues.

In actuality, this kind of a swing was actually a rare occurrence for Downing in the latter years of his career. He was a very good hitter, a player who hit with power, not surprising given his musculature on display here. The size of his thighs and biceps are indications of one of the stronger players in the game, and one of the first to become heavily involved with weightlifting. As fans, we often hear that weightlifting is bad for players, but in the case of Downing it helped resuscitate a career that seemed doomed to mediocrity – or worse.

The other intriguing feature about Downing’s Upper Deck card is his uniform. He is wearing the gray road uniform of the Texas Rangers. For some reason, I have no recollection of Downing as a Ranger. How could this be? After all, I was following baseball closely in the early 1990s.

I remember Downing as a member of the Chicago White Sox and California Angels, but not the Rangers. A check of Baseball-Reference.com confirms that Downing did play for Texas, but it was for only two seasons, at the very end of his career. So I guess it’s understandable that Downing’s time in Texas slipped my mind. And yet, he still managed to post OPS numbers of over .800 each of those seasons, highly impressive for a player who was in his early 40s.

More than 20 years earlier, Downing’s association with professional baseball began in rather undistinguished and unexpected fashion. As a high school player in the Los Angeles area, Downing struggled so much that he was actually cut from the team. He then attended Cypress College, tried out for the team, and was cut again, this time before the season began.

As Downing once told sportswriter Gerry Fraley, his old high school and college teammates would often run into him years later and say, “ ‘How did you ever make it (to the major leagues)? You were terrible. You couldn’t play.’ ”

Even at a young age, Downing refused to give up. He worked hard on his skills by playing what he called “bottle cap baseball,” in which he literally hit bottle caps with a plastic bat. In 1969, he bravely attended an open tryout held by the White Sox. Players rarely receive contracts at such camps, but Downing impressed White Sox scout Bill Lentini, who made him an offer in late August. It didn’t hurt that the White Sox had lost a number of minor league players because of the Vietnam War and needed some new players to fill out the lower ranks of the organization.

Due to his late signing, Downing did not play at all in 1969, and instead debuted the following summer in the Gulf Coast League. The White Sox watched him struggle in 34 games as both a catcher and an outfielder. Downing batted only .219 and failed to hit a single home run.

In spite of his inauspicious debut, the Sox promoted Downing to Appleton of the Midwest League in 1971. This time, they tried him out at third base, in addition to catcher and outfield. He appeared in 99 games, but batted only .246 with three home runs. Downing’s offensive game showed only one positive attribute, a patient approach that resulted in 55 walks.

Though Downing had given the organization little reason to show confidence in him, the Sox decided to challenge him again in 1972, this time sending him to the Double-A Southern League. Somewhat surprisingly, Downing hit far better against the elevated competition. Once again splitting his time between three positions, he hit 15 home runs, drew 82 walks, and recorded an impressive OPS of .856.

After attending Chicago’s spring camp in 1973, Downing received a promotion to the Iowa Oaks of the Triple-A American Association.

He played the first month and a half of the season at Iowa before the Sox promoted him to Chicago. Playing at third base in his major league debut, Downing pursued a pop-up near the dugout. Diving into the dugout, Downing made a terrific catch, but he also tore up his knee as he skidded down the dugout steps. As a result, he missed all of June and July, and part of August. When he returned, he filled in at catcher, third base, the outfield corners and DH. The Sox liked his versatility, but his hitting left something to be desired, as he batted .178 in 34 games.

In 1974, Downing made the Sox’ Opening Day roster and played a fairly significant role on the team. Though undersized for a catcher at roughly 155 pounds, he split time with veteran Ed Herrmann behind the plate, and also filled in as an outfielder and DH. Downing didn’t hit for much of an average (.225), but he showed some power (10 home runs) and a propensity to take bases on balls.

After the season, the White Sox cleared out the catching position for Downing by trading Herrmann. Just when it seemed like Downing might be ready for a breakout, he regressed in 1975, hitting only .240 with an OPS of .680. The Sox gave him another long look in 1976, but he continued to struggle. Then in 1977, he lost the catching job to Jim Essian, a superior defensive catcher.

Frustrated by Downing’s lack of development, the White Sox made him available via a trade that winter. When the White Sox had a chance to acquire Bobby Bonds from the Angels, they included Downing in the deal. Downing and two young pitchers, Chris Knapp and David Frost, headed to the Halos for Bonds, fellow outfielder Thad Bosley and pitching prospect Rich Dotson.

Downing welcomed the trade. Naturally shy and reserved, he had not felt comfortable in Chicago, where he felt too much pressure from the fans and media.

Now he would have a chance to play in his native Southern California, in a more relaxed and friendly environment. Looking for a catcher who could hit, the Angels made Downing their No. 1 receiver in 1978. He played in 133 games, but batted only .255 with seven home runs. Once again, his patience at the plate remained a plus, as he totaled more walks than strikeouts.

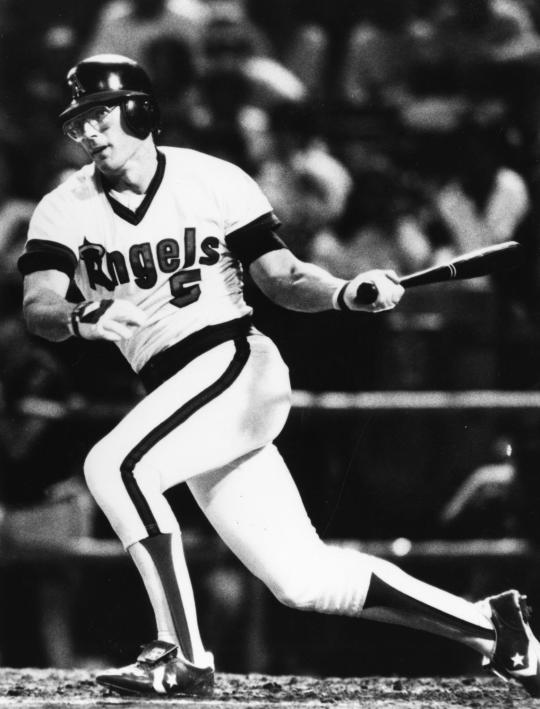

Overall the season left Downing disappointed – and motivated to change his approach. That winter, Downing embarked on an ambitious weightlifting program. At the time, few players in the major leagues lifted weights of any kind – either Nautilus or free weights – but Downing felt that he was too scrawny. He began to lift free weights, hoping to add muscle and bulk to his frame. He also decided to change his batting stance, adopting a radically wide-open position in the batter’s box, which allowed him to see the ball better as it came out of the pitcher’s hand.

Both of the changes paid off immensely. In 1979, Downing hit so well over the first half of the season that he made the American League All-Star team. For the season, he batted .326, slugged .462 and posted an OPS of .880, particularly impressive for a catcher. Downing helped the Angels make the postseason for the first time in franchise history, earning himself some support in the league’s MVP voting.

Given his success, Downing continued his weight training, which became both a hobby and an obsession, to the point that he was nicknamed “The Incredible Hulk,” after the popular comic strip character. One of his motivations came from the movie, Pumping Iron, a documentary about weightlifters at the famed Gold’s Gym, where Arnold Schwarzenegger and Lou Ferrigno trained. By chance, it was Ferrigno who would play the character of the Incredible Hulk on a television show that ran on CBS from 1977 to 1982.

Fully engulfed in weightlifting, Downing reported to Spring Training in 1980, primed for another good season. But then on April 20, in only his ninth game, he broke his ankle. The injury kept him out of action until September, when he returned as a catcher and DH. He would finish the season with a .290 batting average, but that came in only 30 games.

Concerned about a reoccurrence of injury, the Angels decided to switch Downing’s positions in 1981. They made him their regular left fielder and used him only occasionally behind the plate. Though healthy, it was a difficult season, in part because of the long players’ strike that wiped out most of June, all of July, and the early part of August. Downing was also bothered by a balky knee and a badly abscessed tooth, all of which conspired to limit him to a .249 batting average and nine home runs.

Downing now faced another crossroads moment of his career. He was now 30, no longer a catcher, and a player with a reputation for being hurt too often. But with his determination level was hitting a peak, Downing emerged as an offensive force in 1982. Playing in a career-high 158 games, he showed newfound power, clubbing 28 home runs and lifting his OPS to .850. His batting eye became even sharper, as he drew 86 walks against only 58 strikeouts. Downing helped the Angels win the American League West, with his efforts placing him 14th in the league’s MVP balloting.

Over the next six seasons, Downing remained an offensive stalwart. In so doing, he became that rare player, like Mike Easler and Bill Robinson, who was better in his 30s than he was in his twenties. He hit no fewer than 19 home runs a season during that span, reached the .800 OPS level four times and led the American League in walks in 1987 (with 106). In 1986, he contributed to another division-winning Angels team before having to endure a heartbreaking loss to the Boston Red Sox in the ALCS.

Downing’s style of play also made him popular with Angels fans, who were amused when they saw him make a 1985 appearance on the popular comedy, The Jeffersons. (On the show, Downing played himself, as Louise Jefferson snuck into the Angels’ clubhouse looking for teammate Reggie Jackson.) On the field, Downing played the game hard and fully charged, even though he lacked footspeed in the outfield. By 1988, Downing he became a fulltime designated hitter for the Angels, but remained productive that summer, hitting 25 home runs and drawing 81 walks. The following year, his hitting began to decline, but not enough to keep him out of the Angels’ regular lineup.

After an injury-plagued 1990, Downing became a free agent. The Angels did not want him back. In fact, no team showed any interest. With only a week remaining in Spring Training, Downing felt his career had ended.

“Without a doubt, I had given up,” Downing told Steve Pate of The National. “Then I heard word that some people were campaigning for me in Texas. I called my agent and asked him to call Tom Grieve [the Rangers’ general manager].”

Grieve contacted Downing and offered him one-year deal. Despite almost a complete absence of Spring Training, he still managed to put up an OPS of .831. And then in ’92, at the age of 42, he posted an OPS of .835, rather remarkable for a player who had been on the brink of forced retirement.

Though Downing’s continued hitting success indicated he could play for at least another season, his body was beginning to break down, resulting in more missed playing time. He decided to retire after the ’92 season. He and his wife settled into small-town life in Texas, operating a farm with chicken, geese and pigs.

Mostly withdrawing from baseball, Downing has enjoyed retirement away from the spotlight. He has never worked for a team, instead enjoying life in rural Texas. But it’s baseball for which he is most remembered. He stands as the ultimate example of the player who seemingly had no chance, but through hard work, fierce dedication, and constant hustle simply willed his way onto a major league roster.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum