- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1992 Topps Mike Gallego

#CardCorner: 1992 Topps Mike Gallego

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

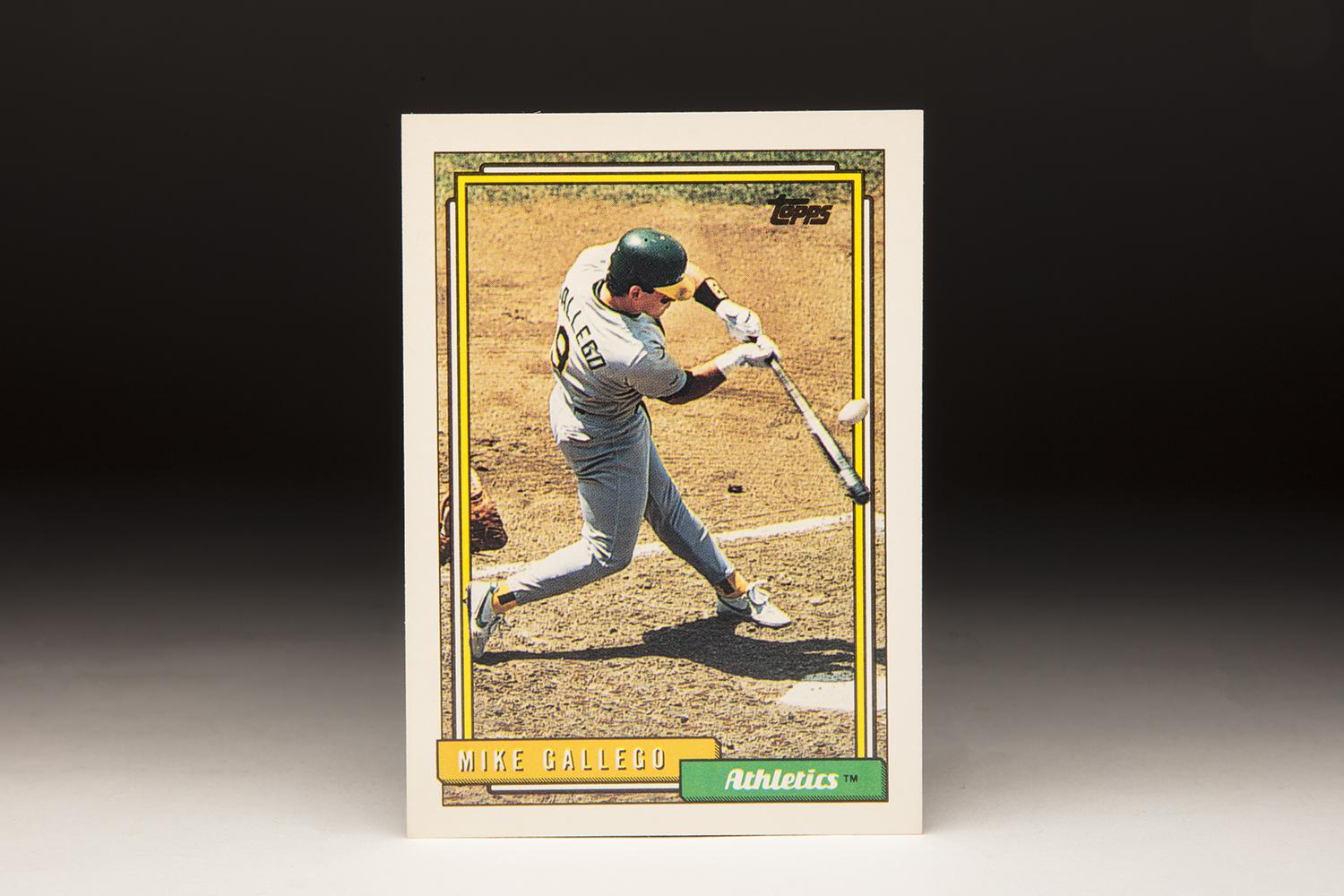

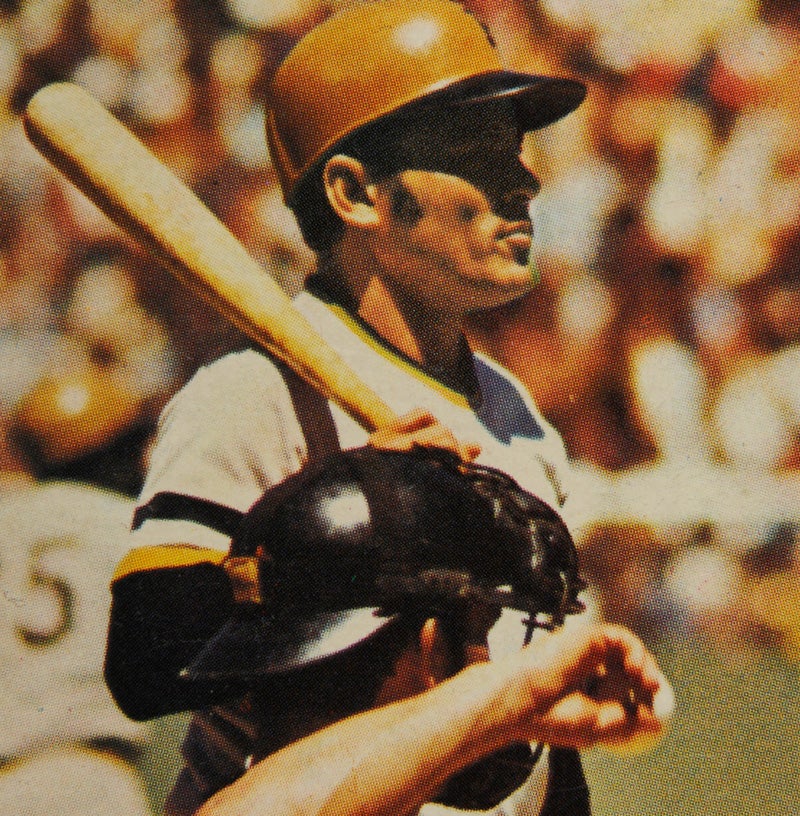

Of all the cards that Topps put out in its 1992 set, this one just might be my favorite. It’s a clear and well-framed action shot, taken during a 1991 game, possibly at Tiger Stadium. I love the angle that the photographer has taken: To the right side of the batter, but not at field level, instead slightly elevated, as if it were taken from the second deck of the ballpark. It’s the kind of angle that I’ve rarely seen on a baseball card.

The 1992 card of Mike Gallego also invites some questions. More specifically, when was the photograph taken? Was it just before Gallego makes contact, or just after the moment that the bat hits the ball? At first, I thought that the picture might have been snapped just after Gallego made contact, but after looking at the card a second and third time, I began to have some doubts.

At this point, I decided to enlist the help of some friends here at the Hall of Fame. I polled four people, two of them who work in our photo department and the other two who work as curators. The first two respondents said that they really couldn’t be sure whether Gallego had already made contact or not. The last two came up with contrasting theories.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Kelli Bogan, the manager of the photo archive, offered this thought: “Very difficult to say. My gut says he has just hit the ball based on leg positions.”

That seemed like a good answer to me. And then, John Odell, our curator of history and research, chimed in with his own reasoning. “I think the ball is incoming. I feel like Gallego’s hands should be turning over if he’d hit the ball and it were outbound.”

Given that we don’t see any bending of the bat, John’s response seemed like a good one, too.

Clearly, arguments can be made in both directions. Really, I have no idea whether Gallego has hit the ball, or is just about to make contact. While the discussion is interesting, the answer doesn’t matter. The fact that a baseball card can create a level of discussion, some real debate, speaks to its effectiveness. If a card can get us thinking, then it has done its job.

Mike Gallego was certainly a thinking type player; he had to be, in order to overcome some of his limits as an athlete. He was smart enough – and tough enough – to avoid the temptations of joining a gang during his youth. Growing up in Pico Rivera, Calif., Gallego was confronted by the members of a gang known as the “Rivera Boys.” They wanted him to join their gang…make that insisted that he join. Gallego told them “no.” He said that he wanted to play baseball instead. The Rivera Boys told him that he would have to fight them and win the fight – or else be forced to join. So Gallego did. He fought the toughest members of the gang and beat them soundly. The Rivera Boys stopped bothering him after that.

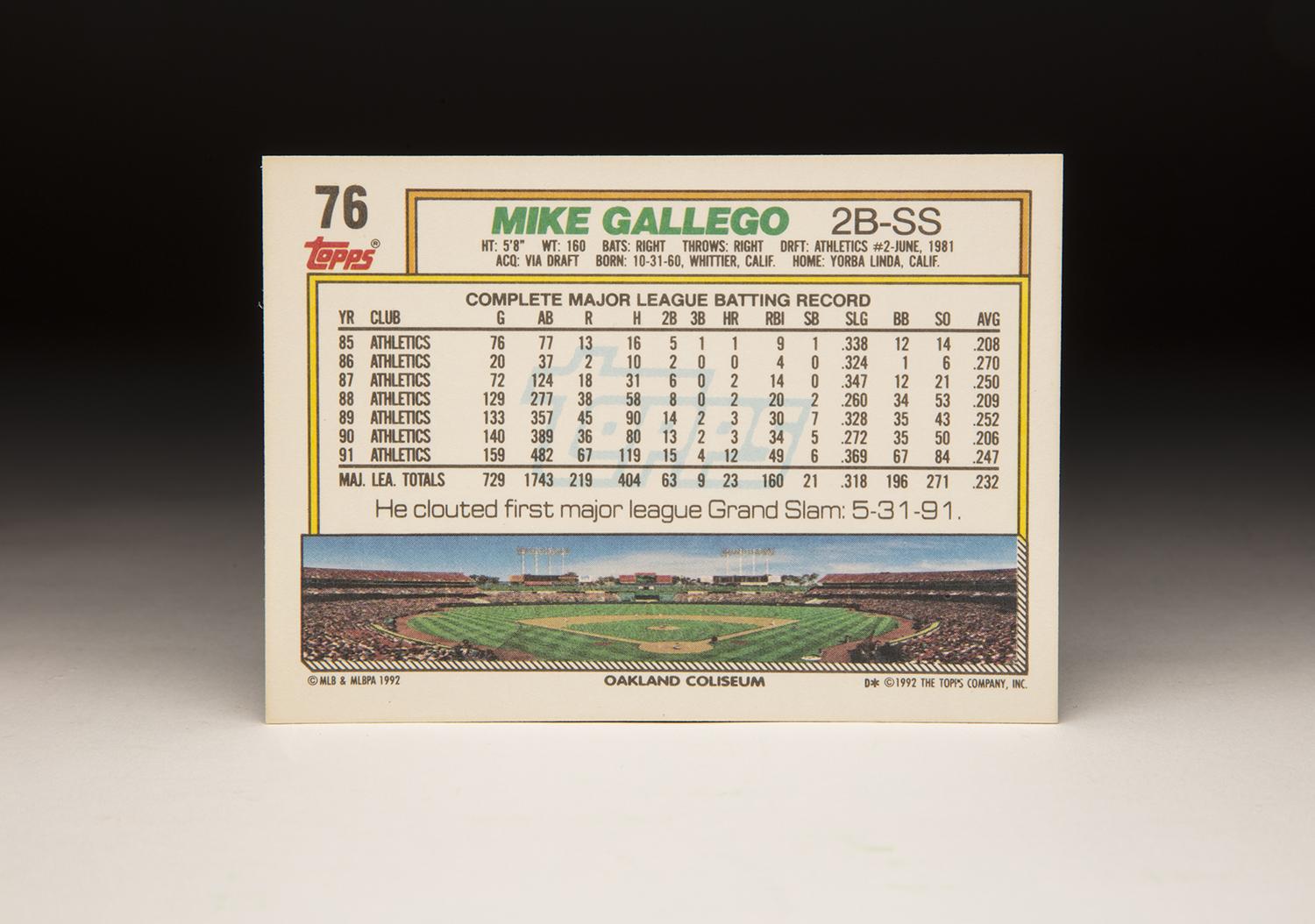

That obstacle overcome, Gallego faced another roadblock. As an amateur ballplayer, Gallego heard the chorus that he was too small. All of 5-foot-5, Gallego idolized Freddie Patek, the undersized shortstop of the Kansas City Royals. Determined to prove coaches and scouts wrong, Gallego enrolled at UCLA, where he played baseball for three years. He played well enough to draw interest from the Oakland A’s, who made him their second-round draft choice in 1981.

By now 5-foot-8, the young second baseman did well as a rookie, hitting .270 for Class A Modesto of the California League. Then his performance stalled, likely the result of being promoted too quickly. The A’s assigned him to Triple-A Tacoma in 1982, where he hit only .221. That resulted in a demotion to Double-A West Haven, where his average plunged to .180.

The worst year of Gallego’s life took place in 1983, when he was diagnosed with cancer in his right testicle. Doctors removed the testicle, reassuring Gallego that the cancer had not spread. But he still had to undergo a full six weeks of radiation treatment. Each treatment made him physically ill. “Like clockwork,” Gallego told Tom Pedulla of the Gannett Suburban Newspapers, “I would get sick three hours after each treatment.”

At first, Gallego felt sorry for himself. But those feelings turned to anger, which he used as a motivational tool. Once the treatments ended, he returned to the playing field and struggled, failing to hit for either average or power. At one point in 1984, someone in the organization told Gallego that he would never make the major leagues, unless he hit .350 or better in the Pacific Coast League. In so many words, Gallego told the naysayer to shove off.

The next season, Gallego proved the naysayer wrong. He made Oakland’s Opening Day roster. A poor start to the season resulted in his return to Triple-A by the early part of the summer, but he made a good impression with his attitude. As Oakland third base coach Clete Boyer said about Gallego: “He was all smiles every day.”

It was not until 1986 that Gallego started to show some promise with the bat. Playing at Triple-A Tacoma, he hit .275 with 39 walks while playing shortstop, second base, and third base. Believing that his hitting had caught up with his very reliable fielding, the A’s brought him back to Oakland for a second look. Serving as a utilityman behind second baseman Tony Phillips, shortstop Alfredo Griffin and third baseman Carney Lansford, Gallego hit a respectable .270 in 40 plate appearances.

That performance served as a springboard to 1987, when Gallego became a fulltime major leaguer. He remained mostly a backup middle infielder, but showed a reliable glove wherever he played and a good grasp of the strike zone in the batter’s box. He batted only .250, but his penchant for drawing walks lifted his on-base percentage to a more presentable .310.

By 1988, the A’s believed that Gallego was ready to take on a greater role. He challenged veteran second baseman Glenn Hubbard, eventually winning the job – at least temporarily. The A’s believed in Gallego because of his fielding ability; he played second base with good range and hands that resembled a Venus fly trap. Regarding Gallego as the American League’s best defensive second baseman, the A’s tolerated his weak bat. He hit only .209 with an on-base percentage that fell below .300.

Gallego hit better in 1989, lifting his average into the .250 range, as the A’s won their first world championship since the days of Charlie Finley. Gallego then fell back into bad offensive habits in 1990. He started the season in a 4-for-44 slump, which prompted the A’s to make a trade for veteran Willie Randolph. The A’s used Gallego as part of a rotation of middle infielders, a system devised by manager Tony LaRussa. (The one consolation to Gallego’s season came in the American League Championship Series, when he hit .400 against Boston, helping the A’s reach the World Series for the third straight time.)

Then came the crossroads season of 1991. It was Gallego’s final year before free agency; a good season could result in a much improved contract, while a bad one could end up in unemployment.

Gallego responded well to the pressure of impending free agency. Reaching career highs in home runs (12) and walks (67), Gallego compiled an OPS of .712, by far the best of his career. He also played a stellar second base, while also filling in at shortstop.

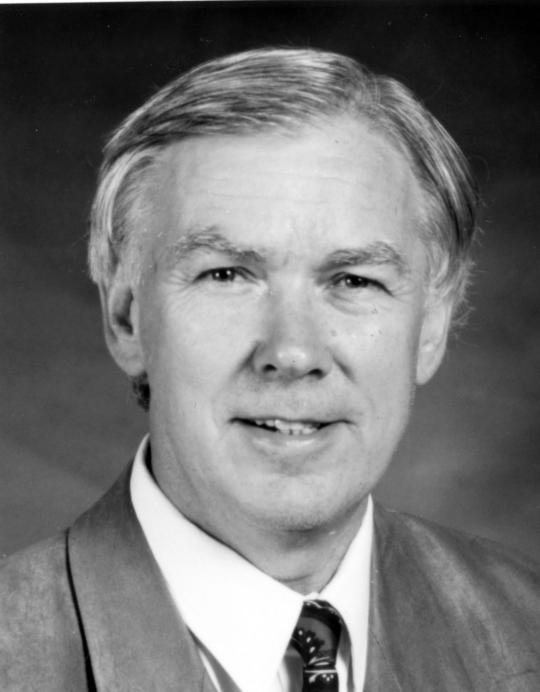

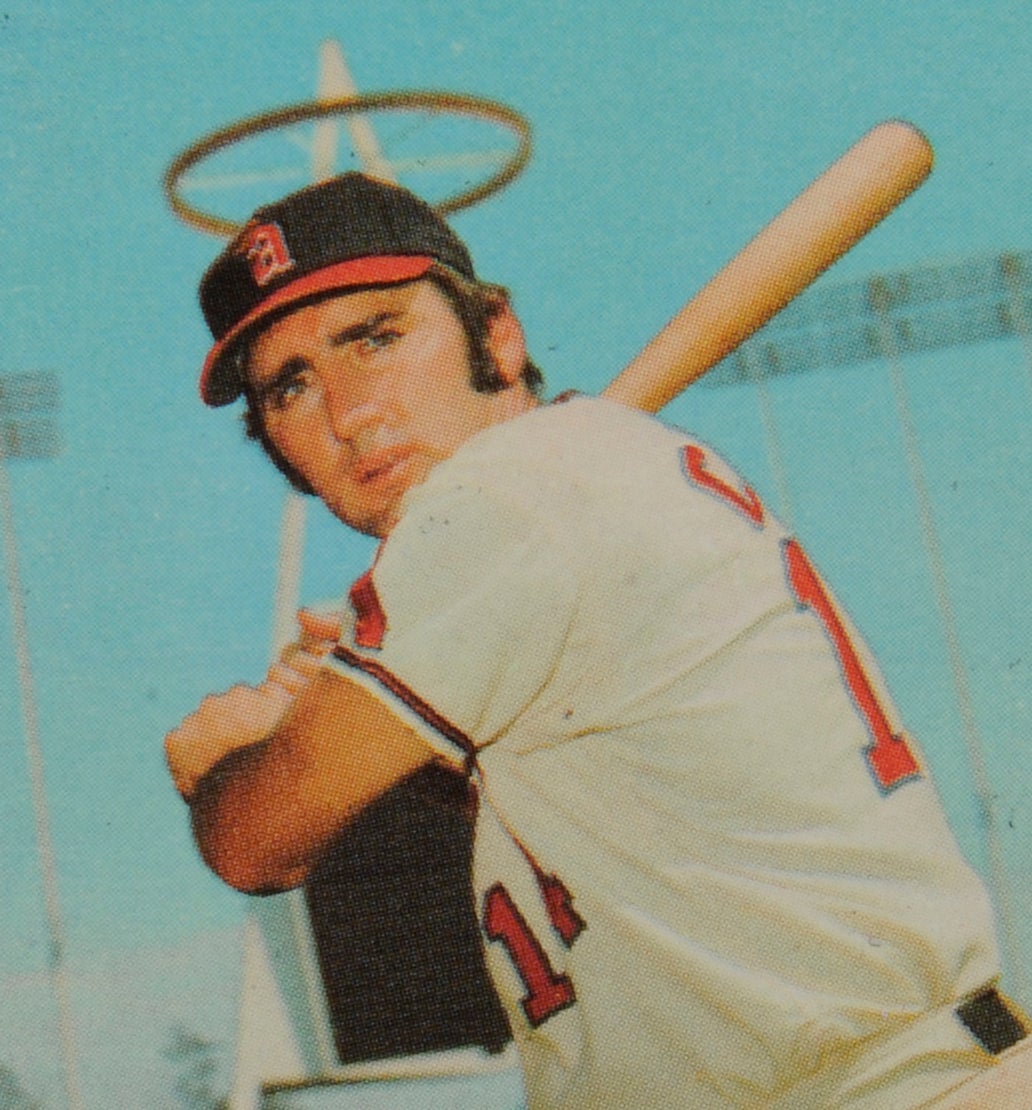

After the season, Gallego declared himself a free agent. As much as he liked Oakland, he knew he could receive more lucrative financial offers from other teams. One such offer came from the New York Yankees and their general manager, Gene Michael, who loved Gallego’s old-style toughness. Michael enticed Gallego with a three-year contract worth over $5 million and the chance to become the Yankees’ starting shortstop. Gallego took the deal and the challenge of playing in New York.

Gallego’s decision to sign with the Yankees gave me a chance to see him play on a regular basis. He had a very distinctive look, like a cross between NBA coach Mike Fratello and veteran actor Ed Marinaro of Hill Street Blues fame. With his short stature, he became an underdog for me, the kind of player that I wanted to do well.

Unfortunately, Gallego’s first year in the Bronx did not go as planned. He had difficulty staying healthy, causing him to lose playing time to Andy Stankiewicz at shortstop. Gallego settled for a utility role, playing behind Stankiewicz and second baseman Pat Kelly. Limited to 53 games, Gallego batted .254, albeit with a respectable .343 on-base percentage. He also faced merciless kidding from some of his teammates.

Outfielder Mel Hall called Gallego “Tattoo,” a reference to the diminutive character played by Herve Villechaize on the TV show Fantasy Island. Gallego didn’t care, brushing off the nickname with a laugh.

Some critics in New York also questioned whether Gallego could play shortstop, with some suggesting that he really belonged at second base. The Yankees ignored most of the criticism. In 1993, they reinstalled Gallego at short and watched him hit .283 with 10 home runs and a .776 OPS. Though he lacked the range of some of the league’s best shortstops, he played solid defense, forming an effective double play combination with Kelly. For the guy who was supposedly too short, couldn’t hit enough and couldn’t play shortstop well enough, the 1993 season represented vindication on every front.

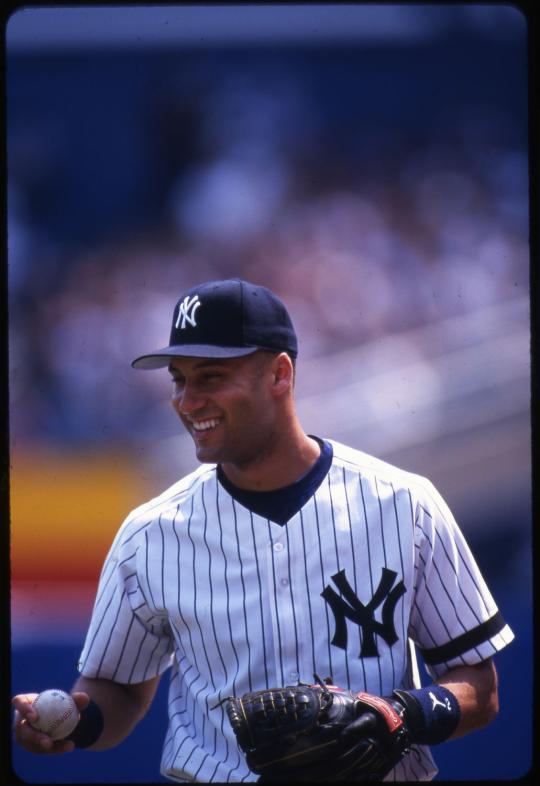

Gallego remained the starting shortstop in 1994, but the strike interfered with his season, along with that of everyone else, while also wrecking the Yankees’ chances of making the postseason. Gallego’s offensive numbers had taken a dip over the first half of the season, but he would have no chance to rebound in late August and September. The strike, which began on Aug. 12, wiped out the balance of the regular season, along with the playoffs and the World Series. Little did Gallego know that he had played his final game for the Yankees. (In a footnote, Gallego also became the last Yankee to wear No. 2 before another shortstop, one named Derek Jeter.)

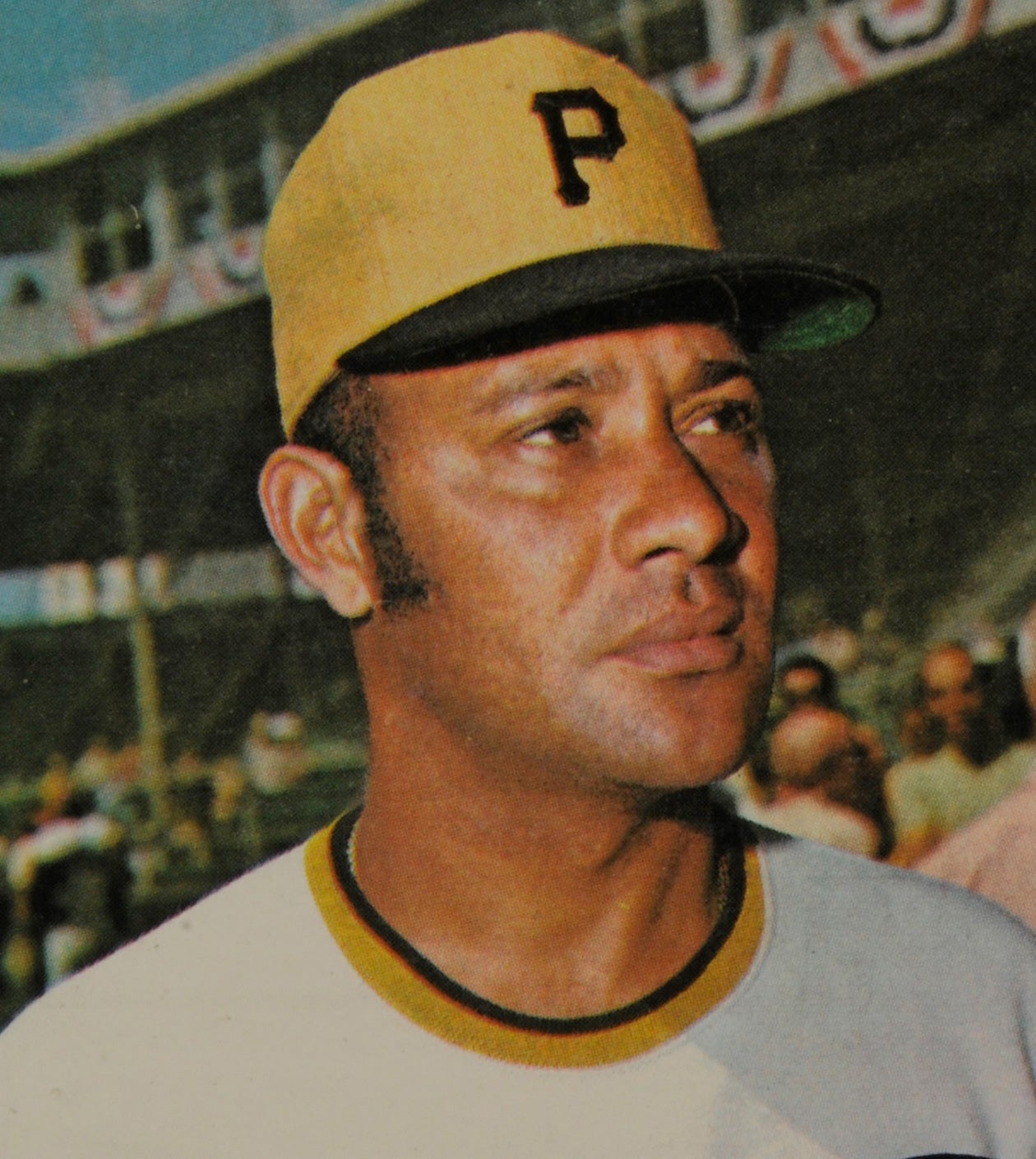

Yankees' general manager Gene Michael loved Mike Gallego's old-style toughness, and signed him to a three-year contract in 1992. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

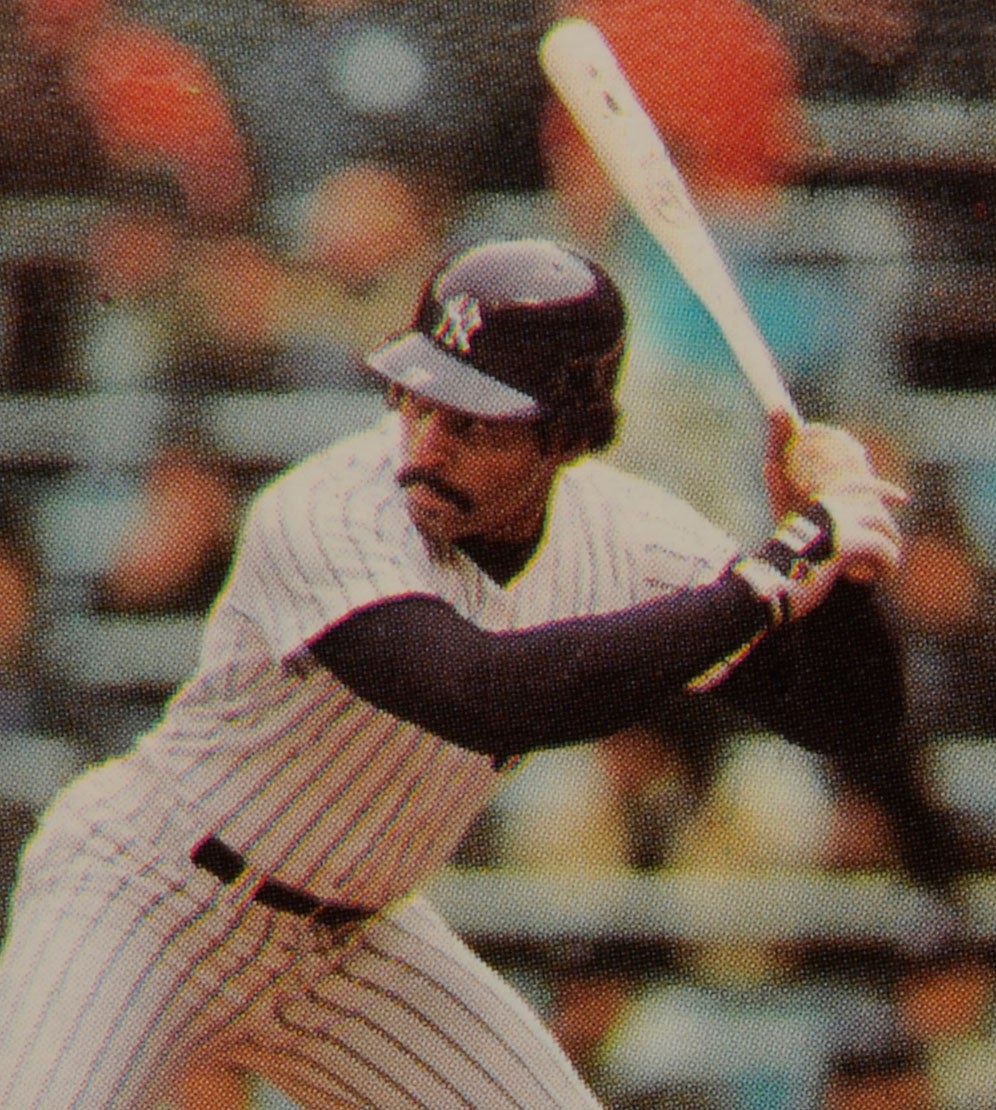

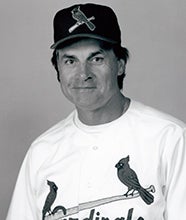

Mike Gallego was reunited with former manager Tony La Russa when he signed with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1996. (Brad Mangin/National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

By the time that the strike was settled in the spring of 1995, Gallego had been declared a free agent. On April 12, two weeks before the start of the strike-delayed season, he signed a new contract with his old team: The A’s. This time Oakland used him as a utility infielder behind their new double play combination of Brent Gates and Mike Bordick. Gallego played sparingly, appearing in 43 games and hitting a subpar .233.

After the season, Gallego again became a free agent. He signed with the St. Louis Cardinals, affording him a reunion with LaRussa, who was now managing the Redbirds. Gallego spent the next season and a half with the Cards as a utilityman, but didn’t hit much. In July of 1997, the Cardinals gave him his release. At 35, Gallego’s time as a major leaguer had come and gone.

To no one’s surprise, Gallego remained in baseball after his playing days. As an overachiever and heads-up ballplayer, it made sense for him to go into coaching. He first served some time with the Colorado Rockies before returning to Oakland as third base coach, a job that he held through 2015. From there, he took a front office position with the Los Angeles Angels.

At 5-foot-8, Gallego sometimes looked out of place on the playing field, especially against the backdrop of supersized athletes like Jose Canseco and Mark McGwire. But Gallego did look pretty comfortable swinging the bat on his 1992 Topps card. And despite the scare that came with a diagnosis of cancer, he managed to sculpt out a nice 13-year career in the big leagues.

Underestimate Mike Gallego all you want, but do so at your own peril.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame