- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1992 Upper Deck Turk Wendell

#CardCorner: 1992 Upper Deck Turk Wendell

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

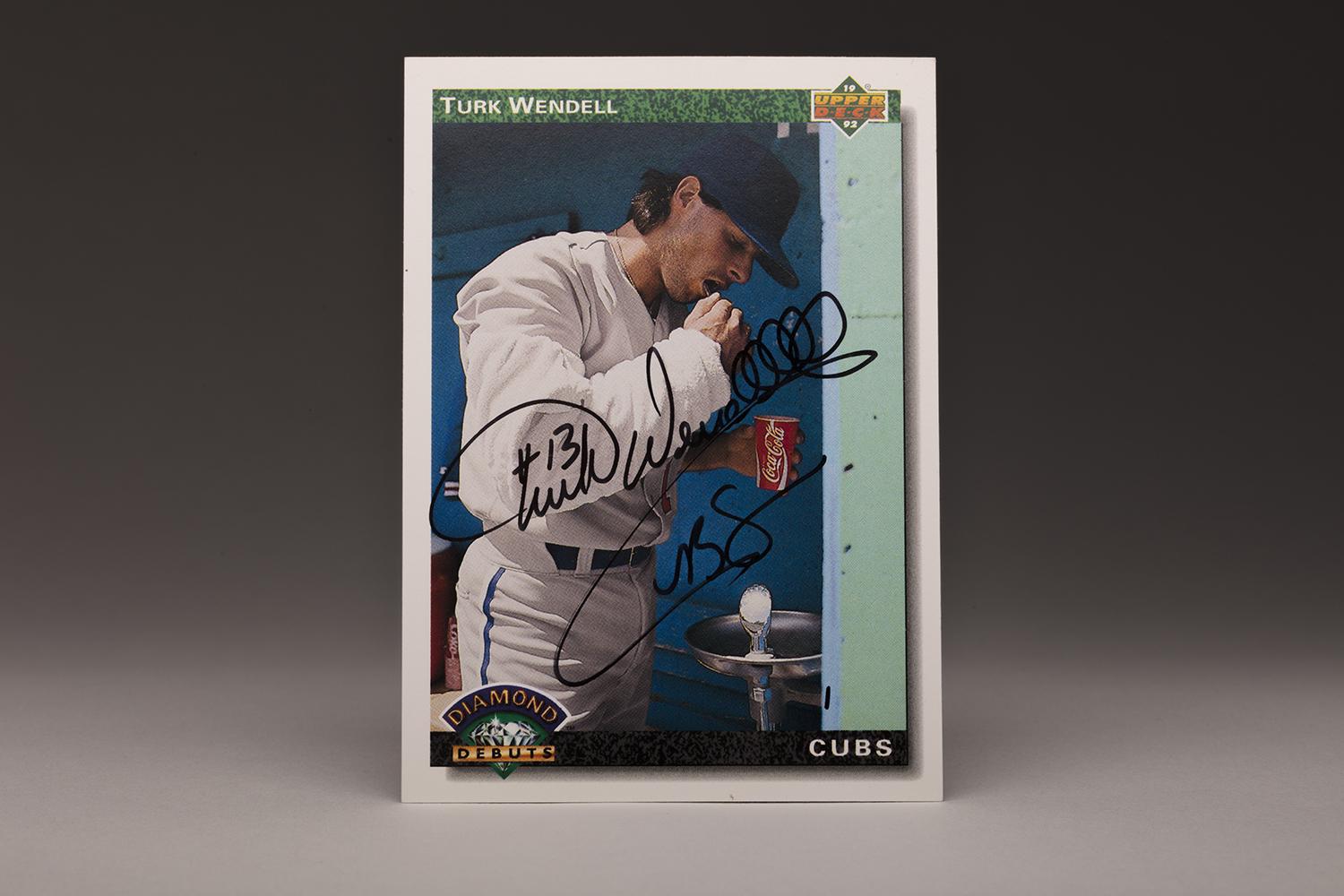

Turk Wendell’s 1992 Upper Deck rookie card is unusual across the board. First, it came out in 1992, a full year before he made his debut with the Chicago Cubs. That explains why Wendell is not wearing the actual uniform of the Cubs, but instead the polyester preferred by one of the Cubs’ minor league affiliates.

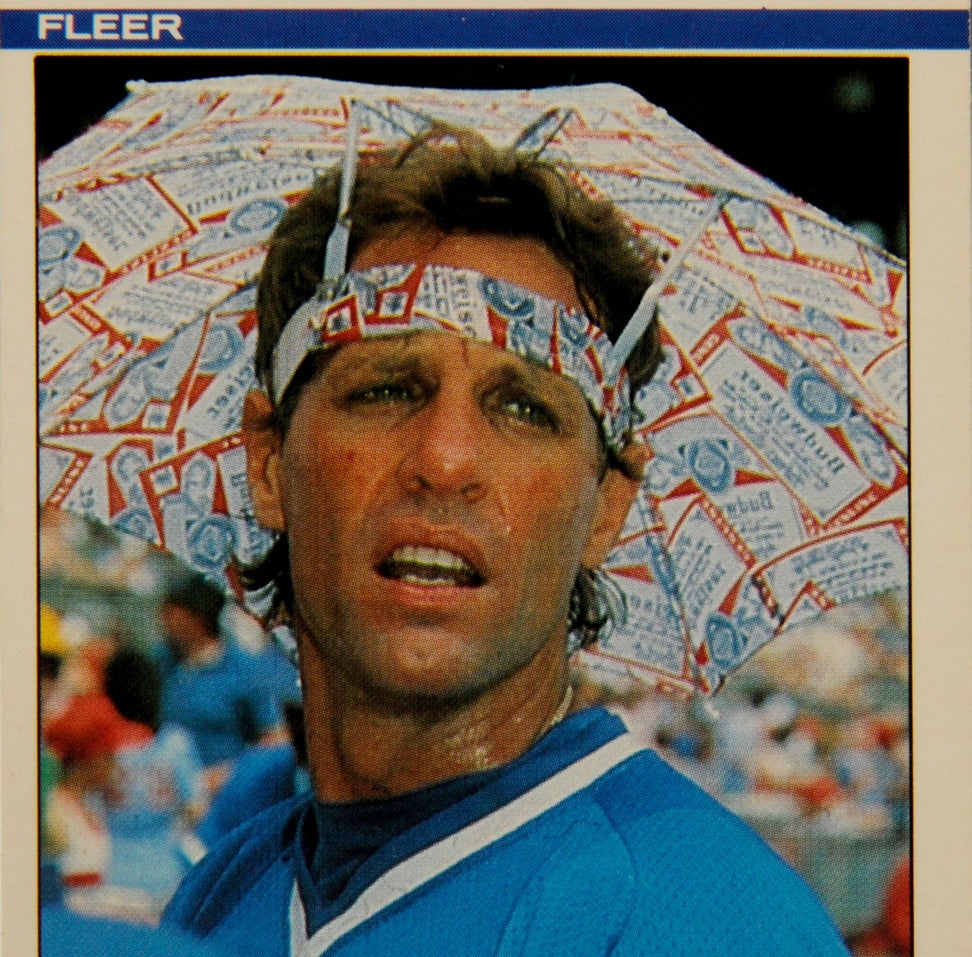

Even more prominently, we see Wendell doing something never before photographed on a baseball card, whether it was issued by Upper Deck or Topps, Donruss or Fleer. Yes, Wendell is brushing his teeth, a habit not commonly on display in any dugout, minor league or major league.

This was no posed stunt done specifically for the Upper Deck cameraman. No, Wendell did this all the time during games. In fact, at the end of each inning he completed, he ran back to the dugout and began brushing his teeth, with all the vigor and enthusiasm that some children used to do in TV commercials for toothpaste. (We can only hope that’s water, and not soda, in the plastic Coca Cola cup.)

By the 1990s, colorfully unusual figures in baseball had almost ceased to exist. With trends toward more corporate public images, ballplayers who provided offbeat postgame comments or contributed to clubhouse and ballpark havoc with their bizarre superstitions had almost completely fallen by the wayside. Thankfully, the likes of Steven John “Turk” Wendell made his way to the major leagues, giving the game a clear connection to its colorful and prankish past.

Wendell’s tendency toward the outlandish began at an early age. When he was all of three years old, he liked to jump out of a window in his house into a mound of snow – face first. The habit earned him the nickname “Turk” from his grandfather, who felt the moniker was appropriate for someone willing to lay himself out in such a fashion. Wendell spent much of his childhood as a daredevil, willing to perform any stunt that most other kids his age would avoid.

Wendell also showed talent for throwing a baseball, eventually making himself a professional prospect. In 1988, the Atlanta Braves spent their fifth-round draft choice on Wendell. He pitched well for the Braves’ minor league affiliates, becoming a prospect, but like some prospects, he turned into trade bait. In 1991, the Braves included Wendell in a trade package with the Cubs, sending him to Chicago for veteran pitcher Mike Bielecki and catcher Damon Berryhill.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

As Wendell worked his way through the minor leagues, he created a stir with his unusually long list of eccentric on-field behaviors, including the aforementioned habit of brushing his teeth. He also chewed black licorice, parodied his catcher’s movements, and slammed the rosin bag onto the pitcher’s mounds. Wendell carried those offbeat habits over to Winter Ball, where he became a favorite of Latino fans. His antics while pitching for Santurce made him a sensation in the Puerto Rican Winter League.

“The fans in Puerto Rico really loved my routine,” Wendell said, “and I pitched extremely well that winter.” Indeed, Wendell was named the league’s outstanding pitcher while finishing second in the Most Valuable Player voting.

In the spring of 1992, Wendell reported to the Cubs’ Spring Training camp in Arizona. His impending arrival caused a stir, with Cubs players pressed to give their thoughts on their new unseen teammate.

“I’d just arrived at Spring Training, and media people were asking me, ‘Have you seen The Turk?’ ” Hall of Fame second baseman Ryne Sandberg told Peter Gammons of The Boston Globe. “Well, to be honest, I’d heard of him, and to be honest, I was kind of curious what he was.”

As much attention as the media paid to his antics, Wendell was far more than just a freak show; he had real pitching talent, the kind that made him one of the top pitching prospects in the Cubs’ organization. He didn’t make the Cubs’ roster in 1992, but by1993 he had earned a spot on the team. Despite the high expectations, he struggled in a handful of starts. The following year, he pitched so poorly to start the season that he received a fast demotion to Triple-A Iowa.

Wendell’s struggles continued in 1995. By this time, the Cubs had converted him from starting to relieving, where they felt he was better suited. Though he showed a live arm, he continued to put up less-than-mediocre results.

Finally, in 1996, Wendell broke through. Becoming a workhorse out of the bullpen, Wendell posted an ERA of 2.84, and struck out nearly a batter an inning. He also earned a reputation as a pitcher who always took the ball, never offering an excuse that he was too tired to pitch.

Wendell’s success also made his circus act more palatable, at least to his Cubs teammates. Some of the Cubs had been critical of Wendell during his first two seasons. “All the shenanigans were fine and dandy, but he wasn’t getting anyone out,” Cubs first baseman Mark Grace told the Chicago Tribune. “A few veterans resented the fact he was doing his antics while he was getting hit hard.”

After establishing himself in the major leagues, Wendell had discarded some of his unusual practices, in part because of the criticism from teammates. At his frenzied peak, most of Wendell’s habits centered on rituals that he performed during each game in which he pitched. They involved such diverse issues as religion and personal hygiene, and sometimes required the cooperation of teammates and even umpires:

• Before Wendell threw his first pitch of an inning, he typically drew three crosses into the dirt on the pitcher’s mound. That accomplished, he turned around and waved to his center fielder, waiting for him to return the gesture. Once the center fielder reciprocated, Wendell turned back to the batter and prepared to deliver his first pitch.

• Wendell habitually chewed black licorice while on the mound, not just for the taste, but because of its appearance. Wendell offered a typically offbeat explanation: “Black licorice looks like real chew, and so does the spit. So, I could look cool, but be a good role model at the same time.”

• When a new ball needed to be put in play, Wendell insisted that the home plate umpire roll the ball toward him on the pitcher’s mound. If the umpire, unaware of Wendell’s preferences, threw the ball back to the mound, the pitcher would either block it with his chest, or allow it to sail past him toward the middle infield.

• Wendell liked to mimic the movements of his catcher, but with a mirror effect. If his catcher stood up, Wendell crouched down. When his catcher bent down to return to his crouching position, Wendell straightened up.

• After recording an out, Wendell picked up the rosin bag from the mound and then ferociously slammed it into the dirt. This ritual became reminiscent of one of Pete Rose’s on-field habits; whenever Rose recorded the final out of an inning, he spiked the ball into the turf near the pitcher’s mound.

• Wendell liked to execute exaggerated jumps on the playing field, a habit that was exacerbated by his superstition. At the conclusion of each inning, as Wendell made his way toward the dugout, he made sure not to step on the foul line, which was an act of bad luck. Instead, he pulled off a dramatic leap over the foul line. The high wire act reminded many of Mark “The Bird” Fidrych, a delightful character from the 1970s.

• Once Wendell arrived in the dugout, he proceeded to brush his teeth vigorously (perhaps to minimize the damage caused by the licorice), usually while facing the dugout wall or hiding behind a teammate.

• Wendell wore No. 99 as a tribute to Charlie Sheen’s “Wild Thing” character in the film, Major League, but he drew far more attention for another accessory he sported. He regularly wore an unusual necklace made up of a variety of teeth and claws, coming from animals that he successfully hunted during the winter months.

It was this latter hobby that produced some of Wendell’s most memorable stories. An avid hunter, Wendell often discussed his exploits in tracking wild animals, including coyotes and his favorite prey, whitetail deer, which he hunted with his own homemade bow.

“The two most enjoyable things I like about hunting,” Wendell said, “is the bond you create with family and friends in the process, and the opportunity for enjoying nature and watching wild life unfold in front of you.” After killing a species for the first time, he ceremoniously took a bite out of the animal’s raw heart, so as to draw himself in union with the beast’s spirit and soul.

Wendell’s love of hunting brought him admiration from some, but plenty of criticism and controversy on other fronts. Wendell’s penchant for controversy may have played a part in the Cubs’ decision to trade him. That tendency, along with a poor start to the 1997 season, resulted in a deal with the New York Mets. The Cubs sent Wendell, outfielder Brian McRae, and reliever Mel Rojas to the Mets for outfielder Lance Johnson and two players to be named later.

Adapting quickly to New York, Wendell settled into a bullpen role with the Mets, putting up an ERA of 2.93 for the balance of the season. He remained effective over the next two seasons. In 2000, he also earned some goodwill during the Mets’ Opening Day trip to Tokyo. Wendell gave up some of his equipment, including sweatbands and broken bats, as gifts to a number of appreciative Japanese fans.

By 2001, when he turned 34, Wendell started to show his age. His pitching slipped. He also became embroiled in controversy that spring. Pitching in an early season game against the Montreal Expos, Wendell hit Vladimir Guerrero with an errant fastball. Guerrero expressed his objections, primarily because he thought Wendell had hit him intentionally. After the game, Wendell sounded off when questioned by reporters. Wendell publicly suggested that Guerrero should return to the Dominican, if he did not like the treatment from opposing pitchers. It was not the polite way to make a statement, but it was typical of the candidness, even the bluntness, of Wendell.

Even seemingly innocent remarks created trouble for Wendell. In professing his love for baseball, Wendell frequently told reporters that he wanted to play his final major league season for free – without a salary. When a reporter informed Wendell that the Players’ Association would not allow him to play free of charge, he responded that he would drop out of the union at the appropriate time. Wendell’s promise became problematic. After all, how would he know which season would be his last would be, given that such decisions are often made at the whim of management, and not the player?

As his pitching effectiveness waned that summer, Wendell became subject to another kind of management whim: A trade. This time, the Mets dealt him in July to the Philadelphia Phillies. The trade was not popular with the New York faithful. In spite of the many controversies, Wendell had become a well-liked figure with Mets fans. His bizarre on-field antics brought cheers from the Shea Stadium faithful, who appreciated his outgoing personality and engaging sense of humor. Though never more than an effective middle reliever for the Mets, Wendell took his rightful place next to Tug McGraw and Roger McDowell as one of the most prominent bullpen screwballs in franchise history.

Wendell also had a serious side that endeared him to New York fans. He liked to participate in baseball clinics for youngsters. He also visited children in New York City hospitals. On one occasion, Wendell paid a visit to the pediatric ward at St. Luke’s/Roosevelt Hospital in Manhattan, where he read the book, The Berenstain Bears Go Out For The Team, for the children who had gathered around him.

Unfortunately, Wendell did not fare as well with the fans in Philadelphia. He flopped badly for the Phillies, his ERA rising above 7.00. He pitched so poorly that he received a number of angry letters from Phillies fans. One letter writer placed the blame of a disappointing Phillies season squarely on Wendell, saying that the team would not make the playoffs because of Wendell’s poor pitching.

In reality, Wendell was pitching for the Phillies with a painful right elbow, an ailment that had bothered him for some time and would cost him all of the 2002 season. Refusing to quit, Wendell worked his back to the Phillies in 2003, and pitched respectably over 56 appearances. The Phillies allowed him to become a free agent at season’s end, so Wendell took his right arm to Colorado, a graveyard for many pitchers. Not so surprisingly, Wendell put up an ERA of 7.02 for the Rockies, who released him in midseason. Unable to predict that his 2004 season would be his swansong, Wendell ended up drawing a regular paycheck from his final team, the Colorado Rockies.

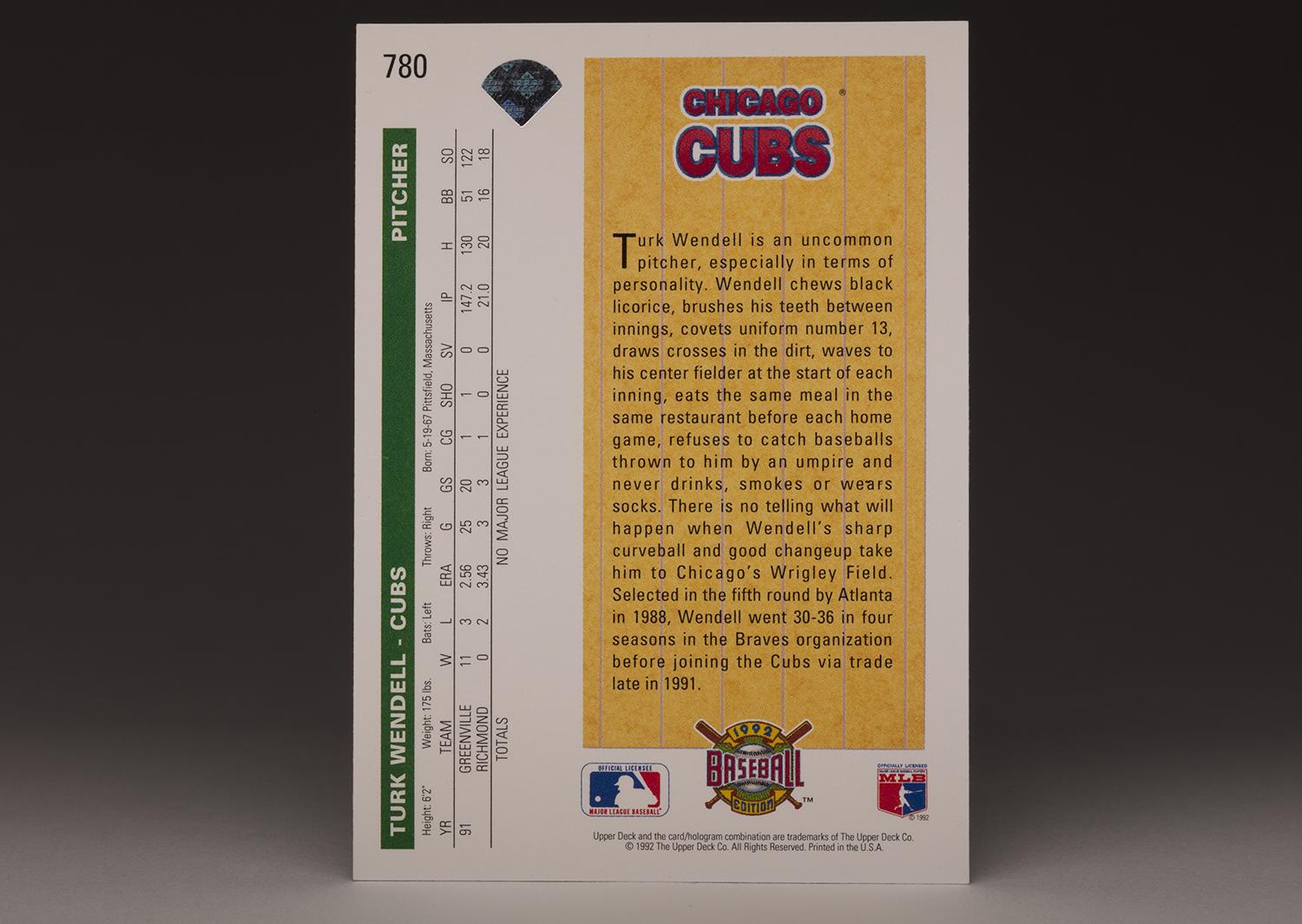

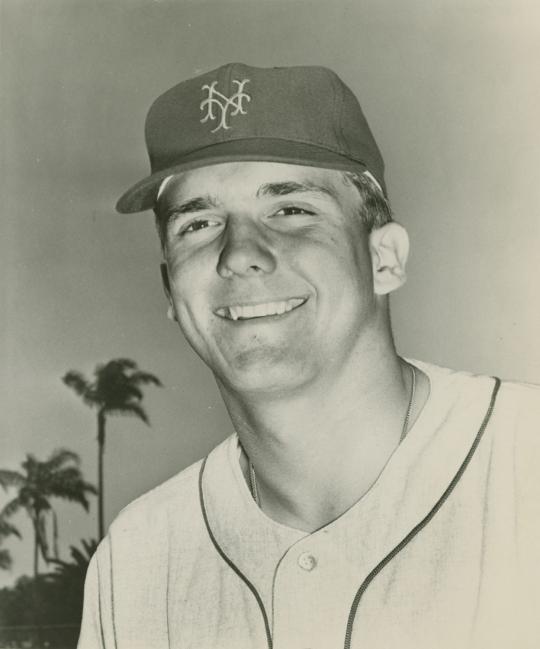

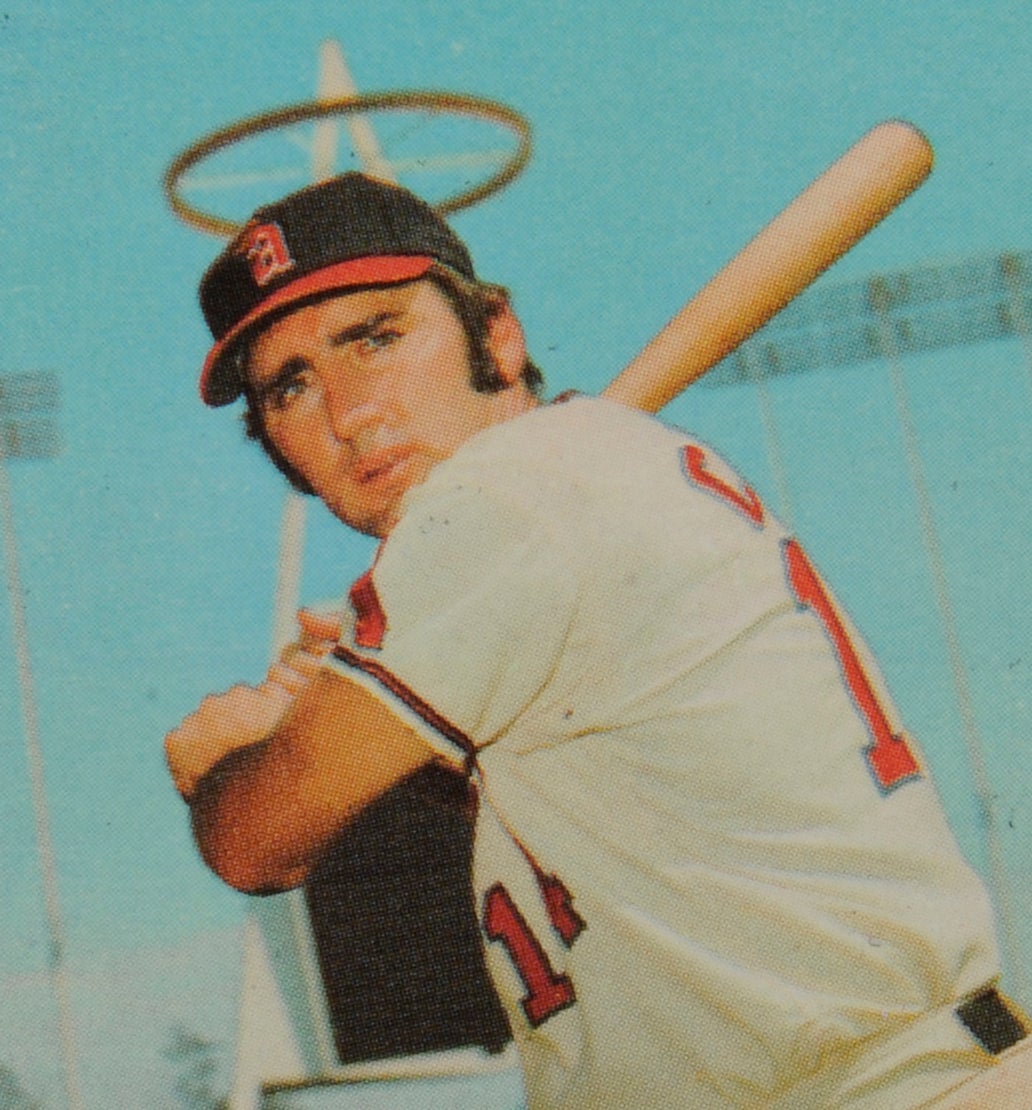

Known for his sense of humor, Turk Wendell was the successor to other offbeat relievers such as Roger McDowell (pictured above). PASTIME (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

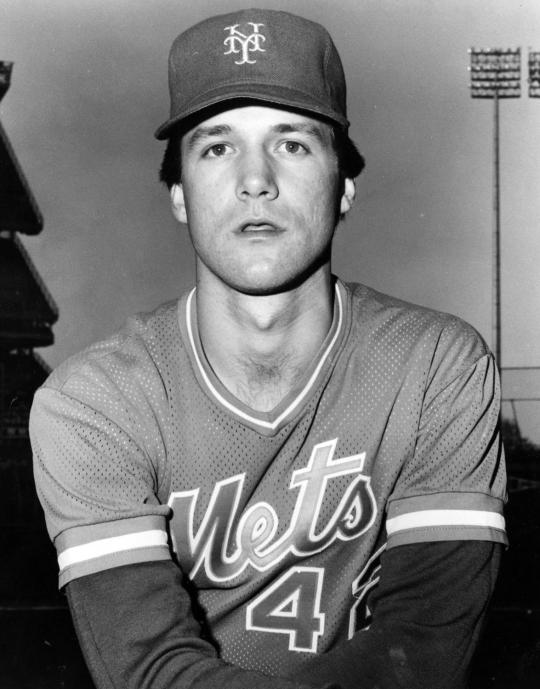

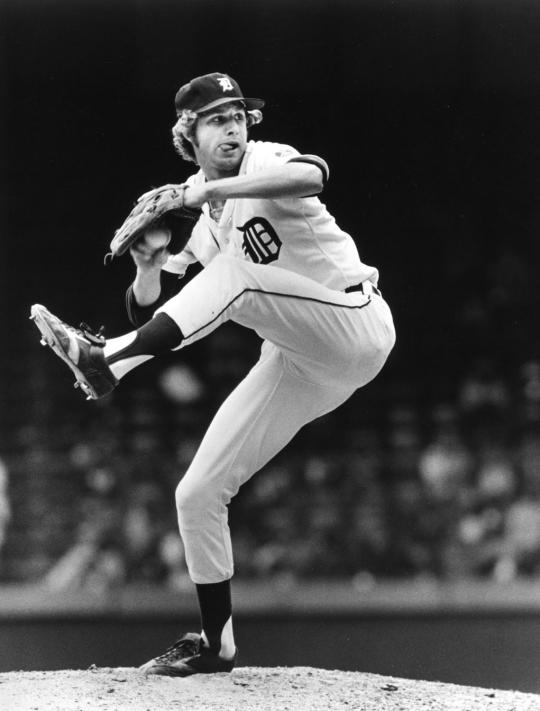

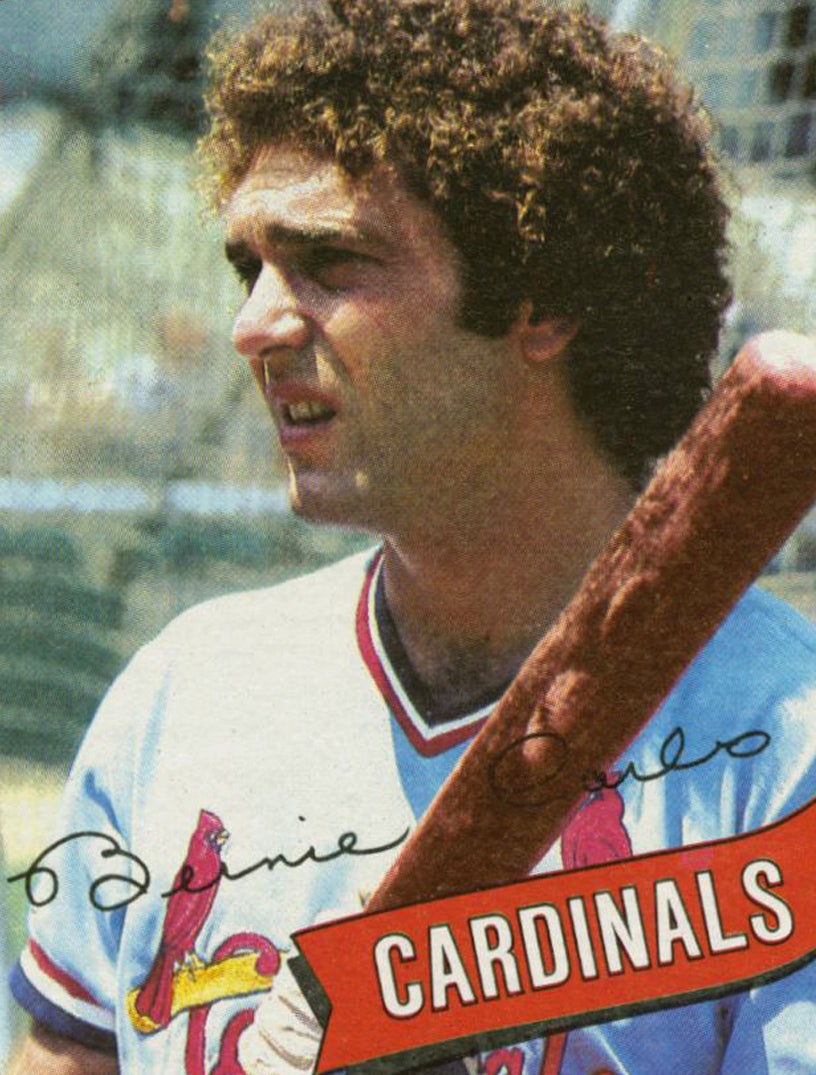

Turk Wendell was traded to the New York Mets by the Chicago Cubs in 1997 and would remain with the team for five years. PASTIME

(National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

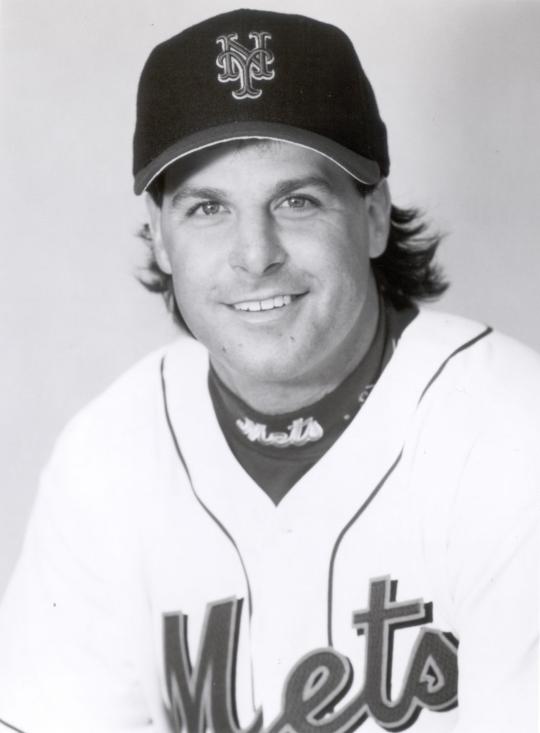

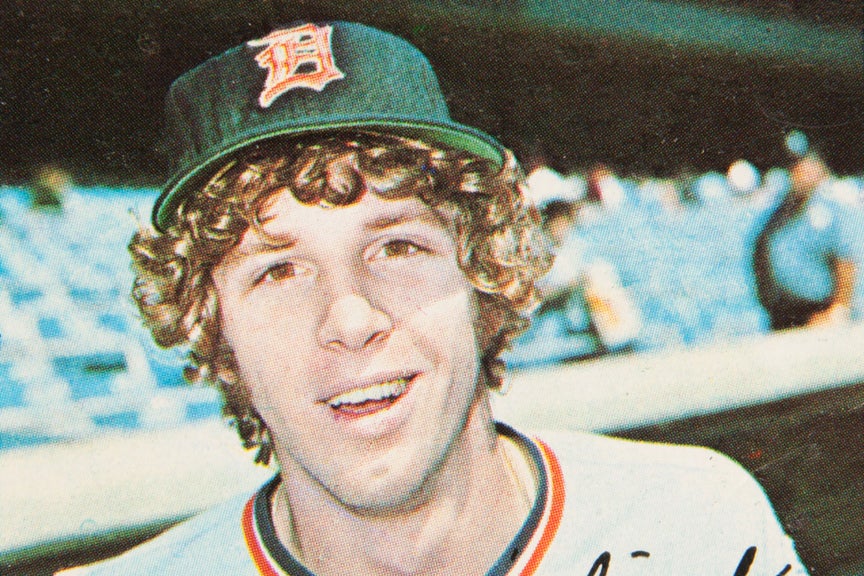

Turk Wendell's colorful personality evoked memories of Tug McGraw, a former relief pitcher for the New York Mets. PASTIME (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

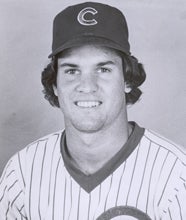

The superstitious Turk Wendell made sure to never step on the foul line as he walked toward the dugout, choosing to dramatically leap over it instead. His actions reminded many of Mark "The Bird" Fidrych, who also chose to hop over the foul line. PASTIME (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

In looking back at Wendell’s career, it might be tempting to dismiss him as just another middle reliever. After all, he never pitched as a closer, and didn’t have any long-term success as a starting pitcher. That’s one way to view his career, but that would be a short-sighted view. Wendell was so much more than just a middle reliever. He was one of the game’s true characters, a modern day answer to a prankster like Moe Drabowsky, a funny man like Sparky Lyle, and a free spirit like Tug McGraw.

In the long tradition of wacky relief pitchers, Wendell brought offbeat behavior, a childlike exuberance, and a unique sense of humor to the game, at a time when perhaps it had become just a little too corporate.

The game of baseball will always need its Turk Wendells.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum