- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1992 Topps Matt Nokes

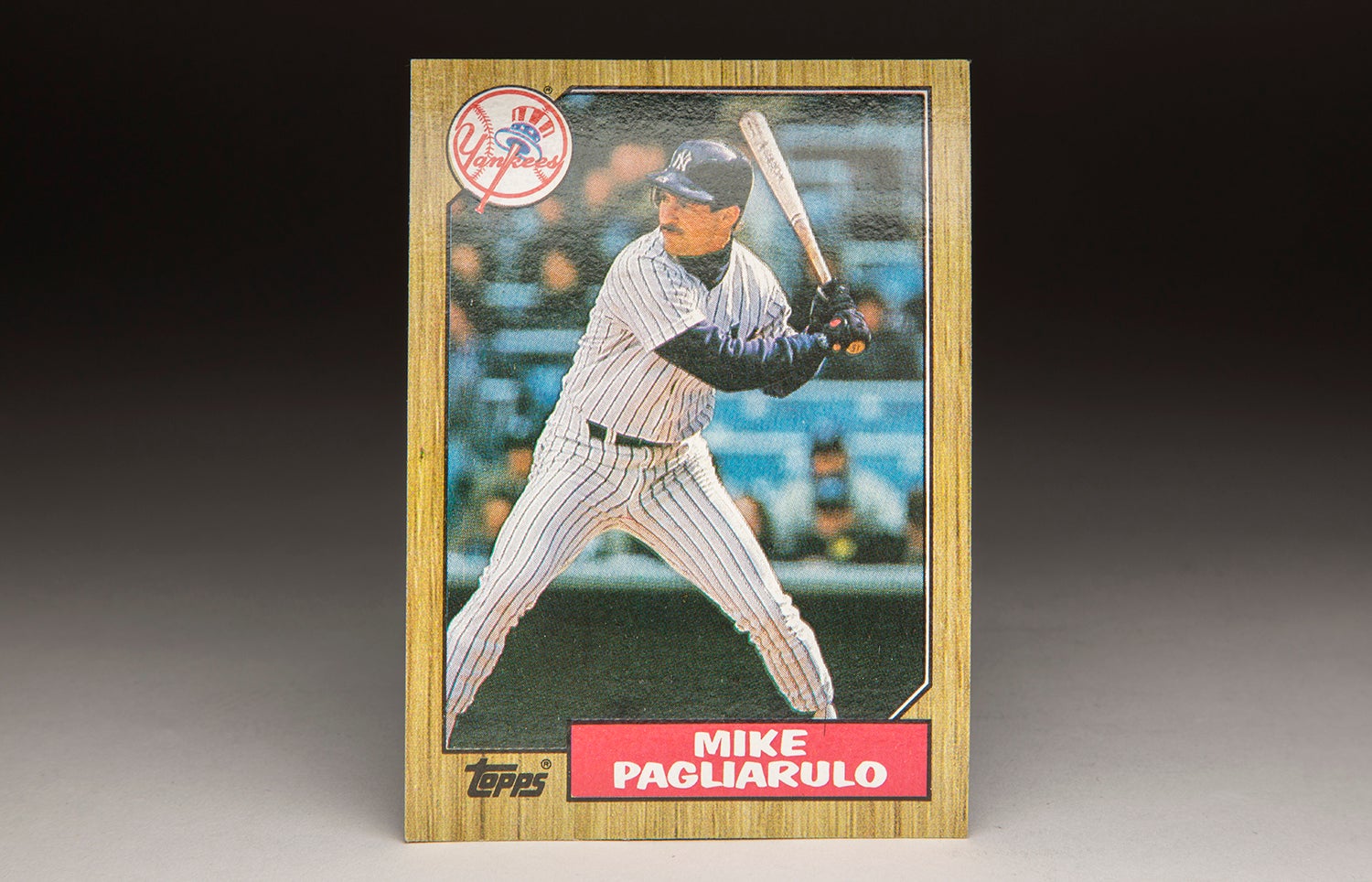

#CardCorner: 1992 Topps Matt Nokes

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Baseball cards can be ironic. How many times do cards show light-hitting players holding a bat, feigning a practice swing, or batting in a real game, in the hope of producing that rare hit? There have also been many cards that show subpar fielders wearing a glove or a mitt while taking a defensive stance in the field. It’s just another part of the strange beauty of baseball cards.

One of the players who fell into the latter category of “good-hit, no-field” was Matt Nokes. Out of all of the Nokes cards ever produced, the majority show him with a bat in his hand; as a dangerous left-handed hitter with considerable power, he was far more comfortable in that aspect of his game.

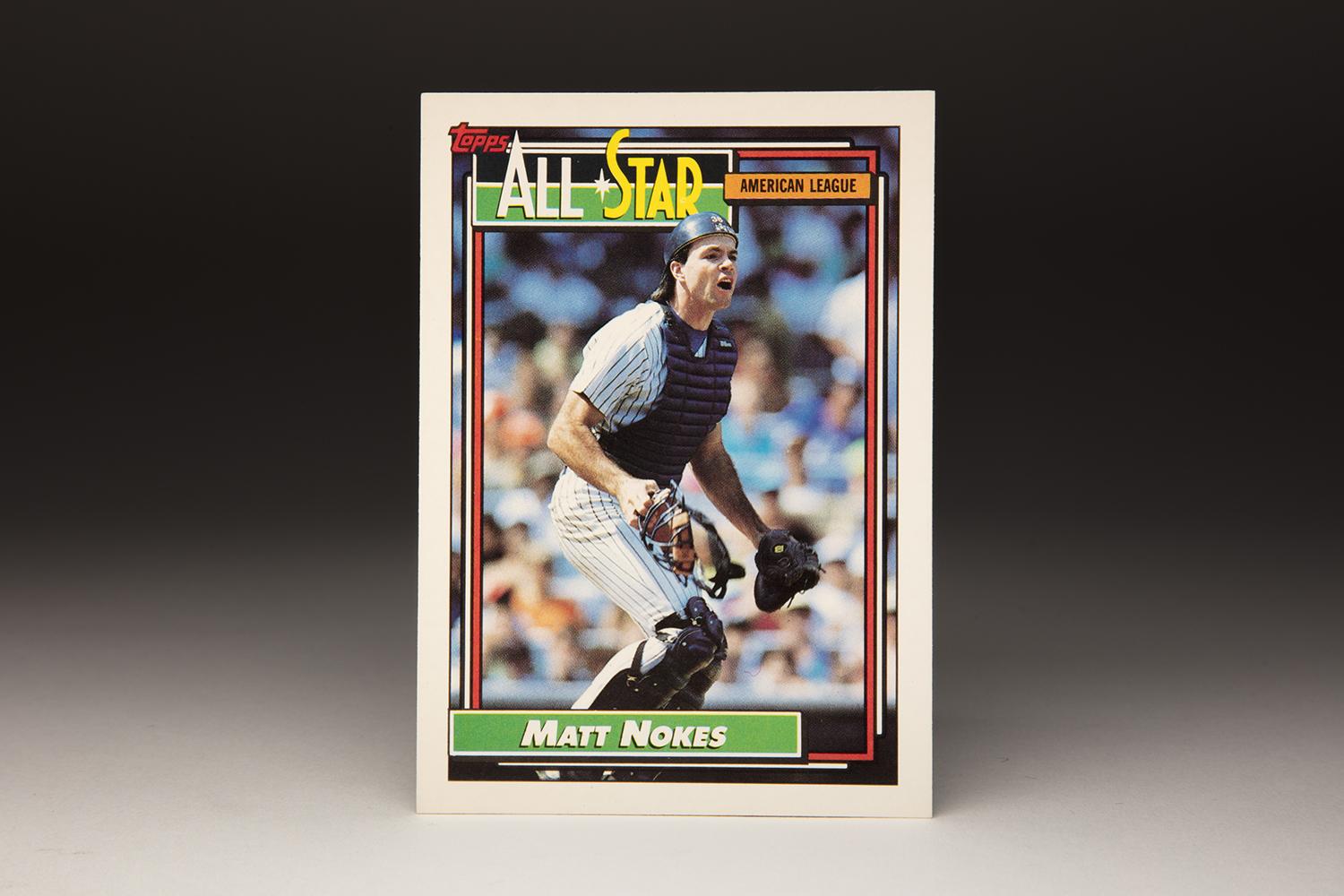

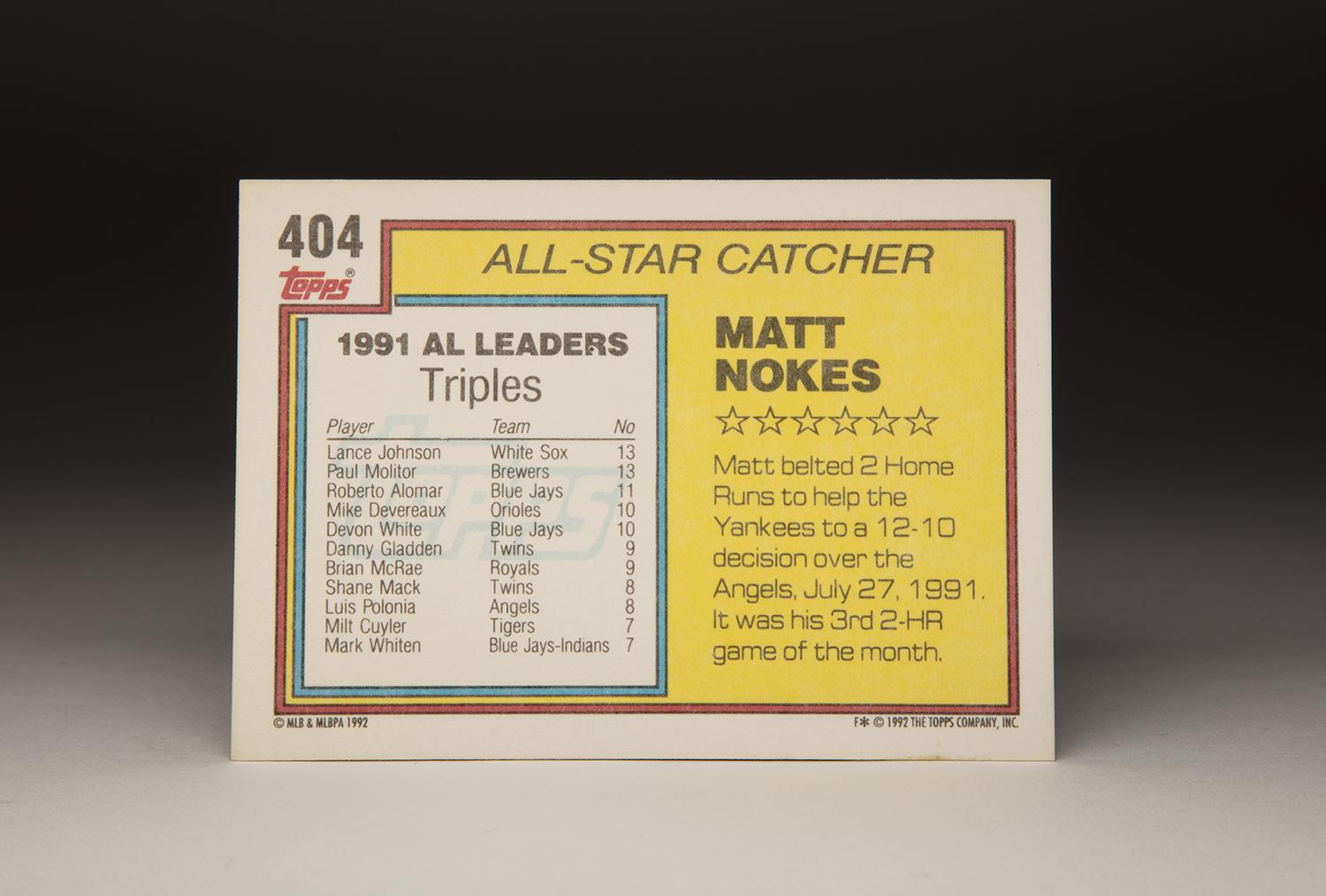

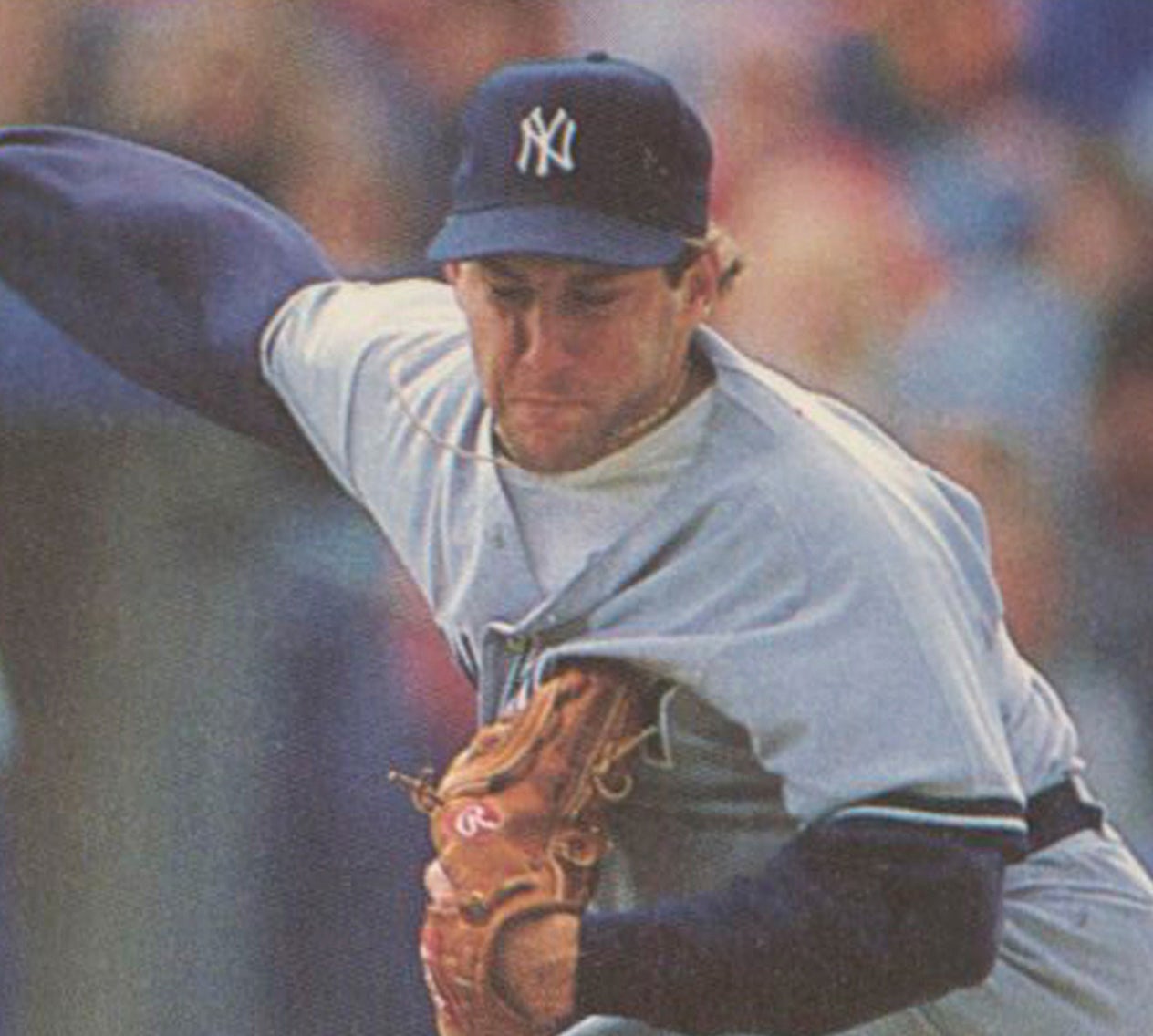

In contrast, only a few of Nokes’ cards show him wearing catcher’s gear and playing the field. One of the cards that placed Nokes in a defensive setting was his 1992 Topps All-Star card, issued 25 years ago. Playing in a game at Yankee Stadium during the summer of 1991, Nokes can be seen in his full catcher’s gear, with his mitt on his left hand and his catcher’s mask in his right hand. Having moved out in front of home plate, Nokes appears to be verbally directing his teammates, perhaps shouting out where to throw the ball. It’s a nicely formatted action shot, one in which Nokes appears quite comfortable and at ease while donning the so-called “tools of ignorance.”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

In disparity with his appearance on this action card, Nokes often struggled when it came to the defensive skills required of a catcher. He moved stiffly behind the plate, sometimes tangling his feet in an effort to block pitches. He didn’t throw well, hampered by bad mechanics and lackluster arm strength. He also had difficulty understanding what pitches should be thrown in certain counts and situations.

That is not to say that Nokes was a subpar player. He was clearly not, as evidenced by the fact that his Topps card showcases him as an American League All-Star in 1991. At one time, Nokes was a hot commodity among major league catchers. He was a left-handed hitting catcher with power, always a rare breed within the game. Back in the late 1980s, when I worked as a talk show host at WIBX Radio in Utica, N.Y., a caller asked my broadcast partner Danny Clinkscale about the possibility of the Yankees acquiring a left-handed hitting catcher. In offering his response, Danny wasn’t optimistic, but offered a memorable response that still sticks with me to this day. “Finding a left-handed hitting catcher is like finding the Rosetta Stone,” he said, making a reference to the priceless black granite stone that bears inscriptions in both the Egyptian and Greek languages.

A few years later, the Yankees somehow did find the Rosetta Stone – in the form of Matt Nokes. In the middle of the 1990 season, the Yankees made a major trade with the Detroit Tigers. They sent two pitchers, Lance McCullers and Clay Parker, to the Motor City for Nokes. Only three years earlier, Nokes had clubbed 32 home runs as a rookie catcher for the Tigers. He seemed destined for a long career in Detroit, where his left-handed hitting stroke made for a perfect match with the short right field porch at Tiger Stadium. Nokes’ ability to pull the ball also matched the dimensions of Yankee Stadium in the early 1990s.

The acquisition of Nokes was exciting for Yankee fans, who needed a boost of energy after watching the team struggle during the latter stages of the 1989 season into the first half of 1990. Frankly, the Yankees of that era needed all the help they could muster; the addition of Nokes appeared to be a small step in the right direction.

Nokes’ professional career had begun nearly a decade earlier. In 1991, the San Francisco Giants signed the 17-year-old catcher to his first contract and assigned him to the outpost of Great Falls, Mont., of the Pioneer League, a Rookie League of rather remote properties. Nokes did not become an immediate success within the Giants’ farm system. He batted only .226 in rookie ball, and then hit even worse in the Midwest League in 1982. It was not until 1983, when Nokes received an assignment to Fresno of the California League, where he broke out with a .322 batting average, 14 home runs and 60 walks.

Nokes was on his way. The following summer, he moved up to the Double-A Texas League, where he played well enough to earn a late season call-up to San Francisco. Appearing in 19 games, he hit only .208 for the Giants, but his ascent to the major leagues at the age of 21 was impressive enough.

As luck would have it, the Giants already had a solid everyday catcher in Bob Brenly, a strong defender with good power. Brenly’s presence made the Giants willing to consider the possibility of trading Nokes, which they did that winter. The Giants included the young receiver as part of a major five-player deal with the Tigers, sending Nokes and pitchers Eric King and Dave LaPoint to Detroit for hard-throwing reliever Juan Berenguer and defensive-minded catcher Bob Melvin.

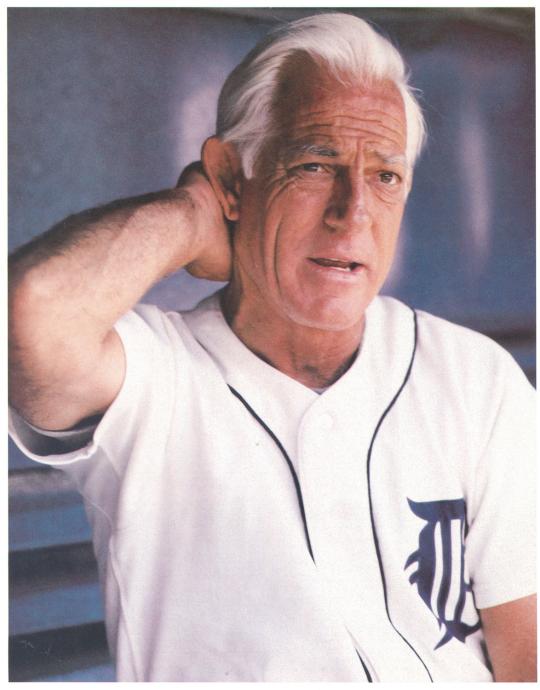

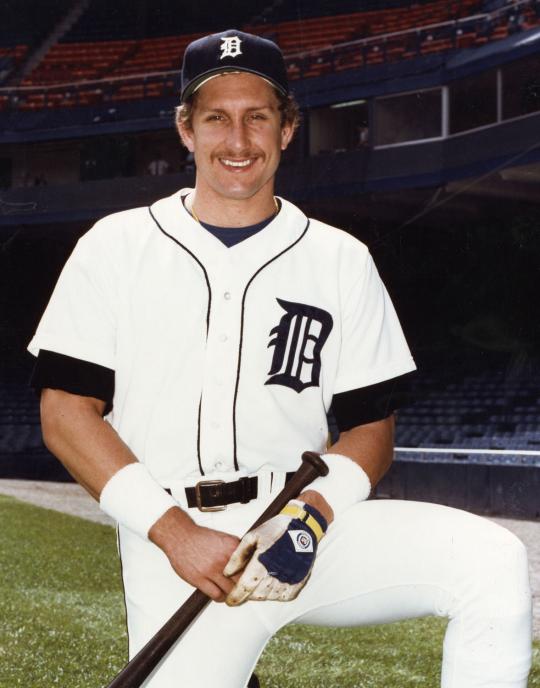

Like the Giants, the Tigers also had a strong starting catcher in Lance Parrish, but he was about to play in the final year of his contract, putting him within striking range of free agency. Nokes played most of the season at Triple-A Nashville, but received a late-season recall from the Tigers, and impressed manager Sparky Anderson during that September cameo. Sure enough, after the 1986 season, Parrish left the Tigers as a free agent, clearing the way for the young Nokes to move into a starting role behind the plate in 1987. Nokes would platoon with veteran Mike Heath, a right-handed hitting catcher with a reputation for premium defense.

The Tigers liked Nokes, not only for his hitting but for his pleasant, even-keeled personality and his willingness to work. Yet they had no idea that he would play like the second coming of Yogi Berra. He hit 11 home runs in his first 51 games, on the way to a 32-home run season, which became even more impressive given how often he sat down against left-handed pitching. He also slugged .536 and posted an OPS of .880, which is simply phenomenal for a catcher. Nokes earned a berth on the All-Star team, finished third in the Rookie of the Year balloting, and even received a few votes in the MVP voting, as he helped the Tigers win the American League East.

In retrospect, Nokes considered his rookie season to be almost dreamlike. “It was a fairy tale season,” Nokes once said in an interview with Sports Collectors Digest. “I couldn’t do anything wrong. It was one of those things. Wherever I played, first base once in a while… I’d make diving plays, it was unbelievable.” As a hitter, Nokes shined against low pitches, particularly fastballs. He could hit low fastballs like few hitters, sometimes falling to one knee to golf a pitch off his shoe tops into the right field stands.

In 1988, American League pitchers began to realize that Nokes could kill low fastballs, but struggled against curveballs. So they threw him more and more breaking pitches, resulting in reduced power numbers for Nokes. On a broader level, just about everybody’s offensive numbers began to decline in 1988. The 1987 season had been one of extreme offensive performance for many players, not because of steroids but because of something that appeared to be going on with the manufacturing of baseballs. Nokes would hit only 16 home runs in 1988. He would never hit 32 home runs again; in fact, he would never come close to matching that number.

He also lacked patience at the plate, a heightened concern for a player who usually batted in the .250 to .260 range. Clearly, he wasn’t the next Parrish or Bill Freehan, as some Tiger fans had been led to believe during the summer of ‘87.

Then there were those defensive shortcomings. Tigers pitchers didn’t particularly like to throw to Nokes, who lacked the knowledge that Parrish had of American League hitters. By 1990, the Tigers had decided they wanted a stronger defensive presence behind the plate. So they made Heath their No. 1 catcher and dispatched Nokes, sending him to the Yankees for the two pitchers.

During his first half season with the Yankees, Nokes struggled, his batting average dipping to .238. His defensive play remained a concern, just as it was during his days in Detroit. The following spring, several Yankee pitchers lobbied for Bob Geren, a stronger receiver and thrower, to become the No. 1 catcher ahead of Nokes. Yankee general manager Gene Michael admonished the pitchers for their complaints.

Even more importantly, Yankee management laid out a plan to help Nokes. Prior to the 1991 season, they hired former big league catcher Marc “Booter” Hill as their bullpen coach. As a ballplayer with the San Francisco Giants, St. Louis Cardinals, and Chicago White Sox, Hill was known for being a voracious eater and for his habits as a prankster. He liked to give hotfoots to teammates, or fill their caps with shaving cream. As a Yankee coach, Hill would take on a far greater responsibility: Working one-on-one with Nokes.

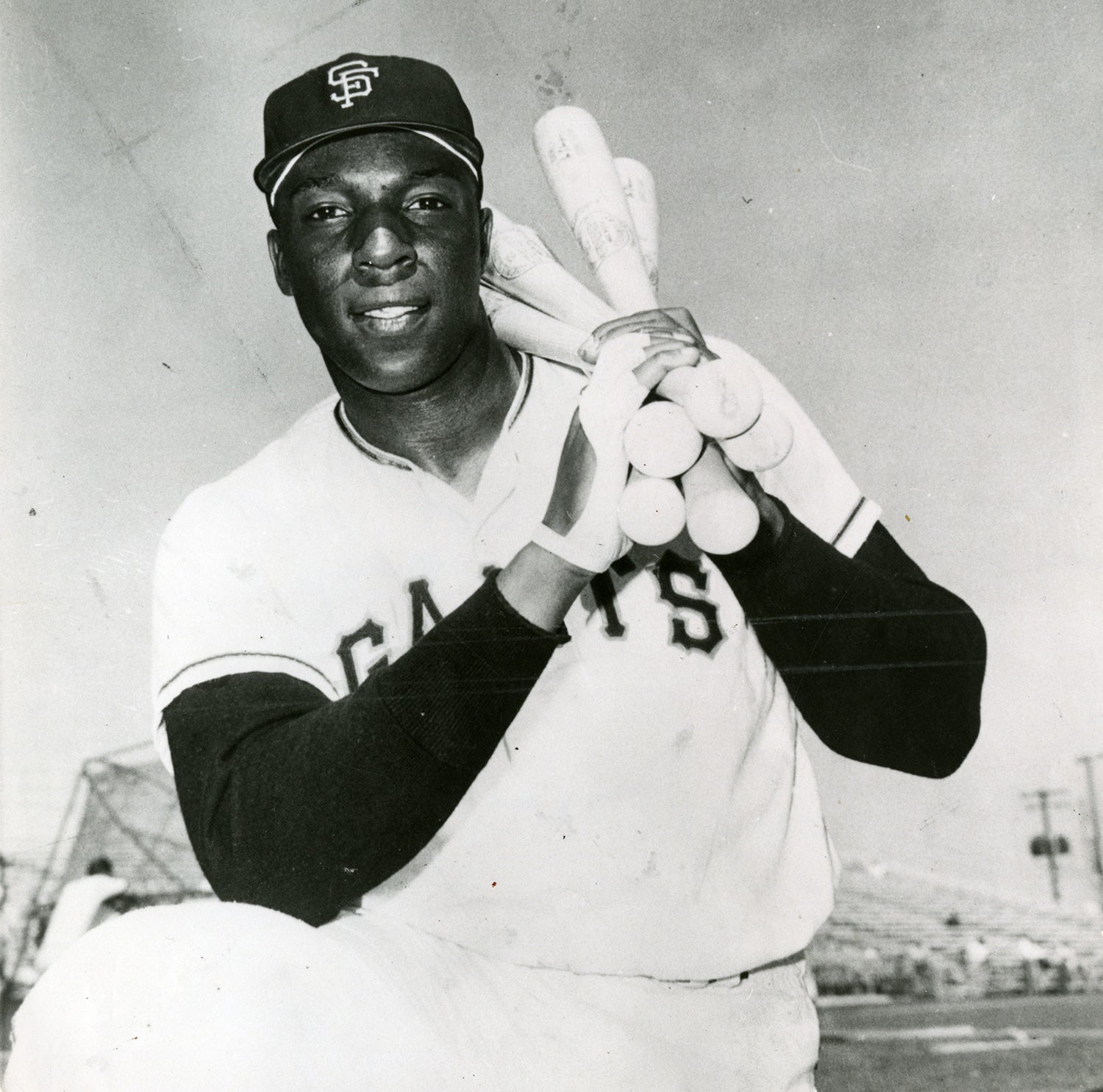

Putting in hundreds of hours with Nokes in 1991, the oversized Hill, who had been nicknamed Booter by former Giants teammate Willie McCovey, helped Nokes in every area. Showing the same work ethic that the Tigers had seen from him in Detroit, Nokes improved his mobility behind the plate, his throwing mechanics, and his pitch-calling skills. Anyone who watched the Yankees that season could see the improvement in Nokes by July and August. He had become a passable defensive catcher, which coupled with his offensive firepower, made him an asset to a rebuilding team. With 24 home runs and a .469 slugging percentage, Nokes put up his best offensive numbers since his rookie season of 1987.

Thanks in part to Hill, Nokes had resuscitated his career. So how did the Yankees reward Hill after the season? They fired him. Citing other areas of Hill’s coaching responsibility, the Yankees decided that Hill’s work with Nokes didn’t justify a spot on the coaching staff. Predictable results ensued. The following season, Nokes fell back into many of his earlier defensive habits. His offensive play also fell off, perhaps a by-product of his defensive woes.

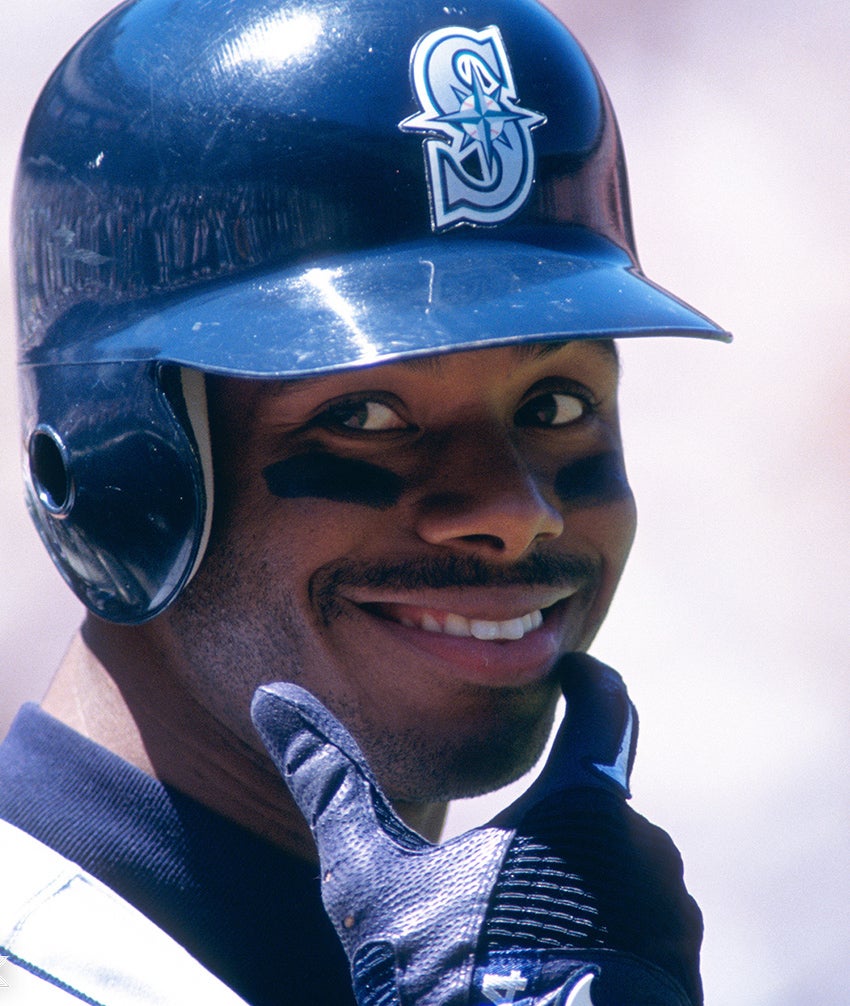

Unfortunately, Nokes’ value only decreased over the 1993 and ’94 seasons. The situation reached a low point in 1994, when Nokes broke a bone in his right hand and missed two months. After his return, he and pitching coach Billy Connors became involved in an incident during a game with the Seattle Mariners. The two began shouting at each other in the Yankees’ dugout. Nokes had called for a fastball from Melido Perez, but the pitch resulted in a 415-foot home run for Ken Griffey, Jr. Connors questioned the wisdom of calling for the fastball, a sentiment that Nokes did not appreciate. The two bickered about the pitch for several moments, in full view of TV cameras, before Yankee manager Buck Showalter stepped in and separated the two combatants.

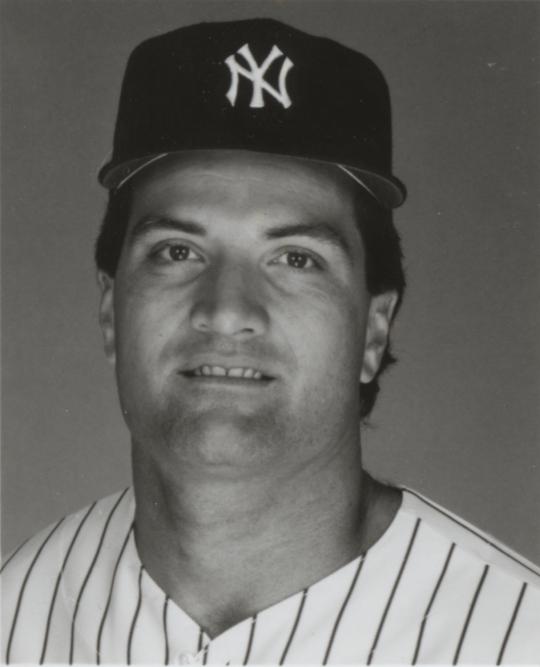

Catcher Matt Nokes received a late-season recall from the Tigers in 1986, and impressed manager Sparky Anderson (pictured above) during that September cameo. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

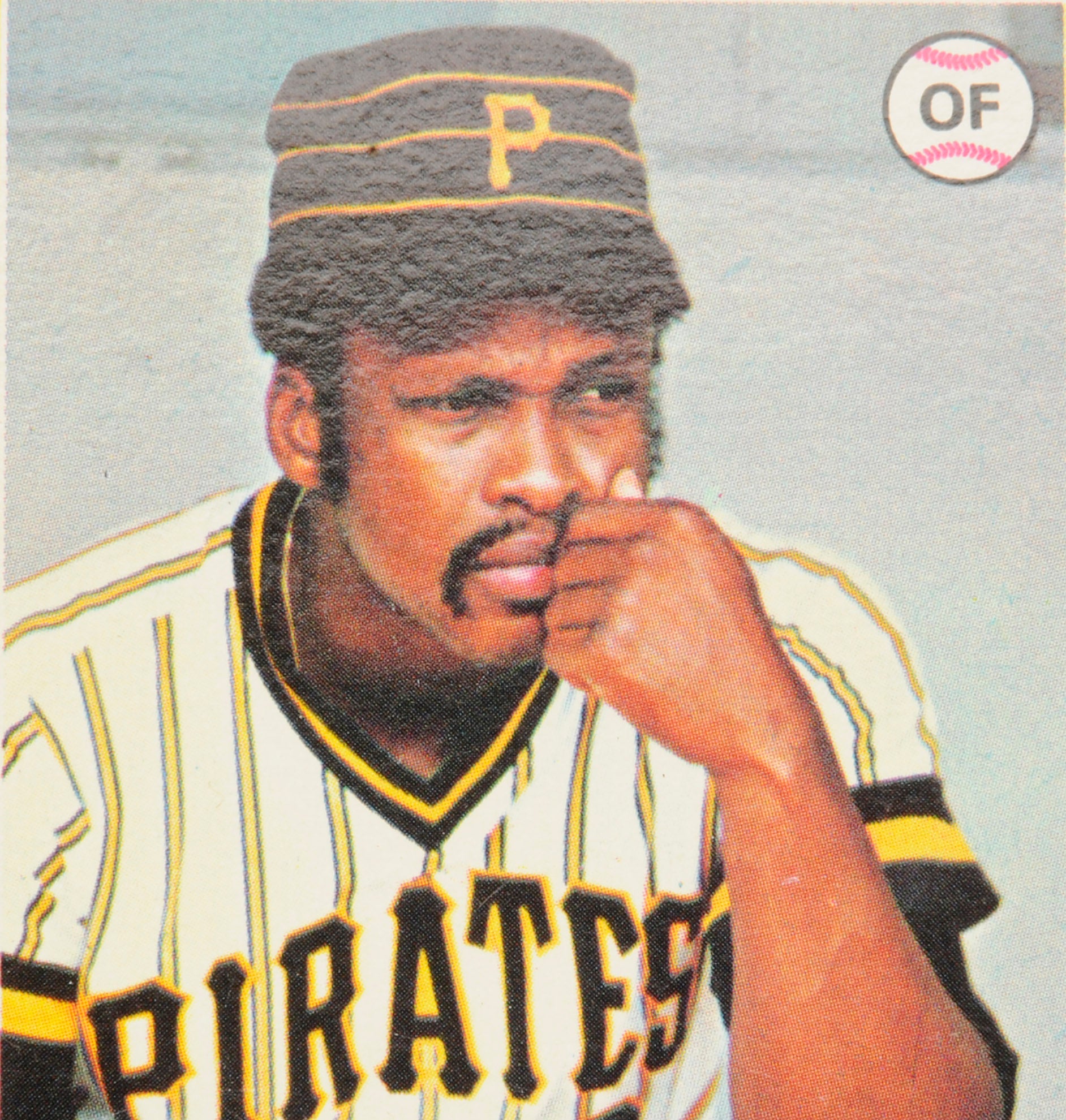

Lance Parrish was selected to eight All-Star Games, including five straight beginning in 1982. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

With his game in full decline at the relatively young age of 31, the Yankees let him become a free agent. As a result, he missed out on the team’s playoff berth in 1995. No longer a premium player, Nokes signed a contract with the Baltimore Orioles, where he played briefly but didn’t hit well. The Orioles allowed him to become a free agent in mid-season, so Nokes took his catching gear to Colorado, but his hitting did not improve. After the season, he decided to extend his career in the Mexican League. He later signed with the independent minor league team, the St. Paul Saints, where he played for two seasons.

Nokes did not easily give up the dream of playing the game. In 2000, half a decade since last appearing in a big league game, Nokes signed a minor league contract with the Cleveland Indians, who invited him to Spring Training. But Nokes failed to make the Indians’ roster, finally ending his attempt at a return to the major leagues.

Nokes opted to remain in the game as a coach, something he continued to do for the next decade and a half. Now retired from Organized Ball, Nokes lives in his native San Diego, where he puts in time as a sort of hitting consultant, offering instruction to young hitters hoping to advance within the amateur ranks.

That kind of vocation makes perfect sense for Nokes, a player who was always willing to work and who always found a comfort zone in the batter’s box. The game will always have room for a left-handed hitting catcher who knows how to swing the bat. After all, that is baseball’s version of the Rosetta Stone.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum