- Home

- Our Stories

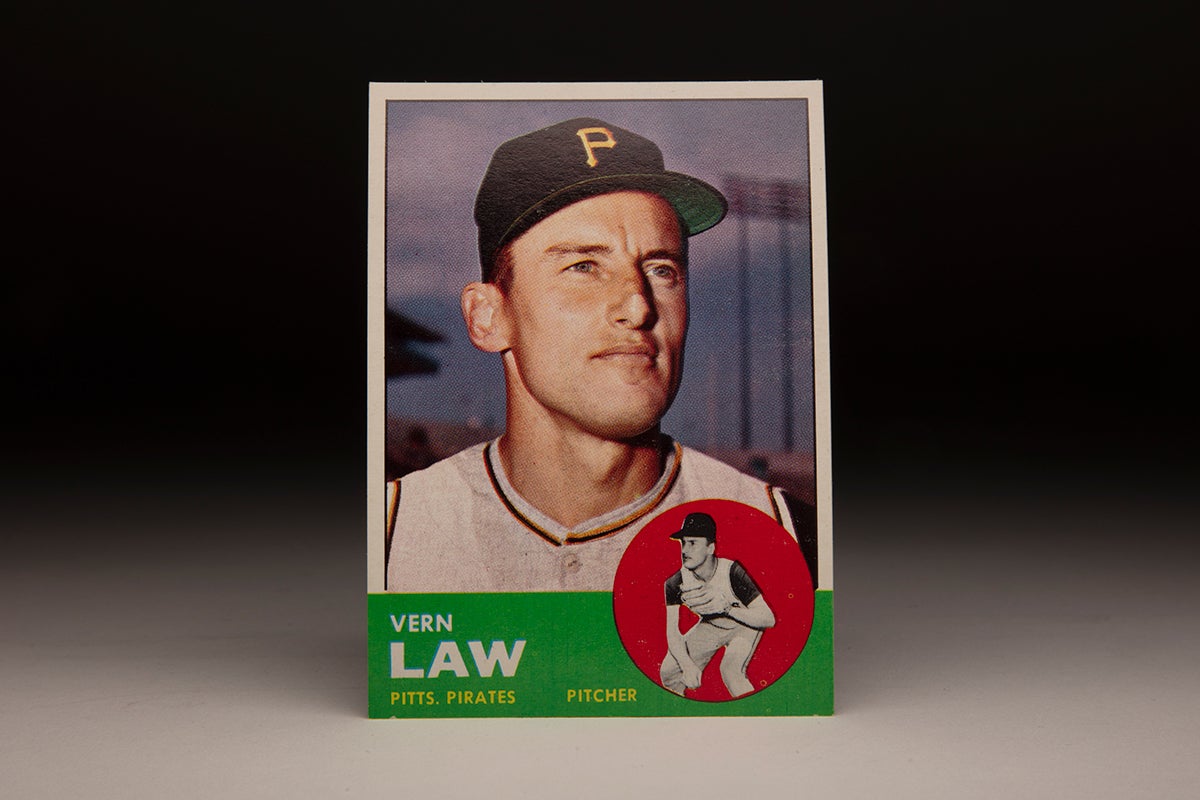

- #CardCorner: 1963 Topps Vern Law

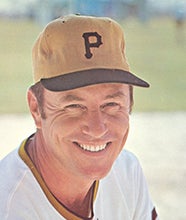

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Vern Law

Hall of Famer Bill Mazeroski will forever be credited with the first Game 7 World Series walk-off home run in history, a blast that gave the Pittsburgh Pirates the title.

But without the pitching of Vern Law, Mazeroski’s homer likely never takes place.

Law’s three World Series starts – made mostly in pain – were the highlight of a season for the ages.

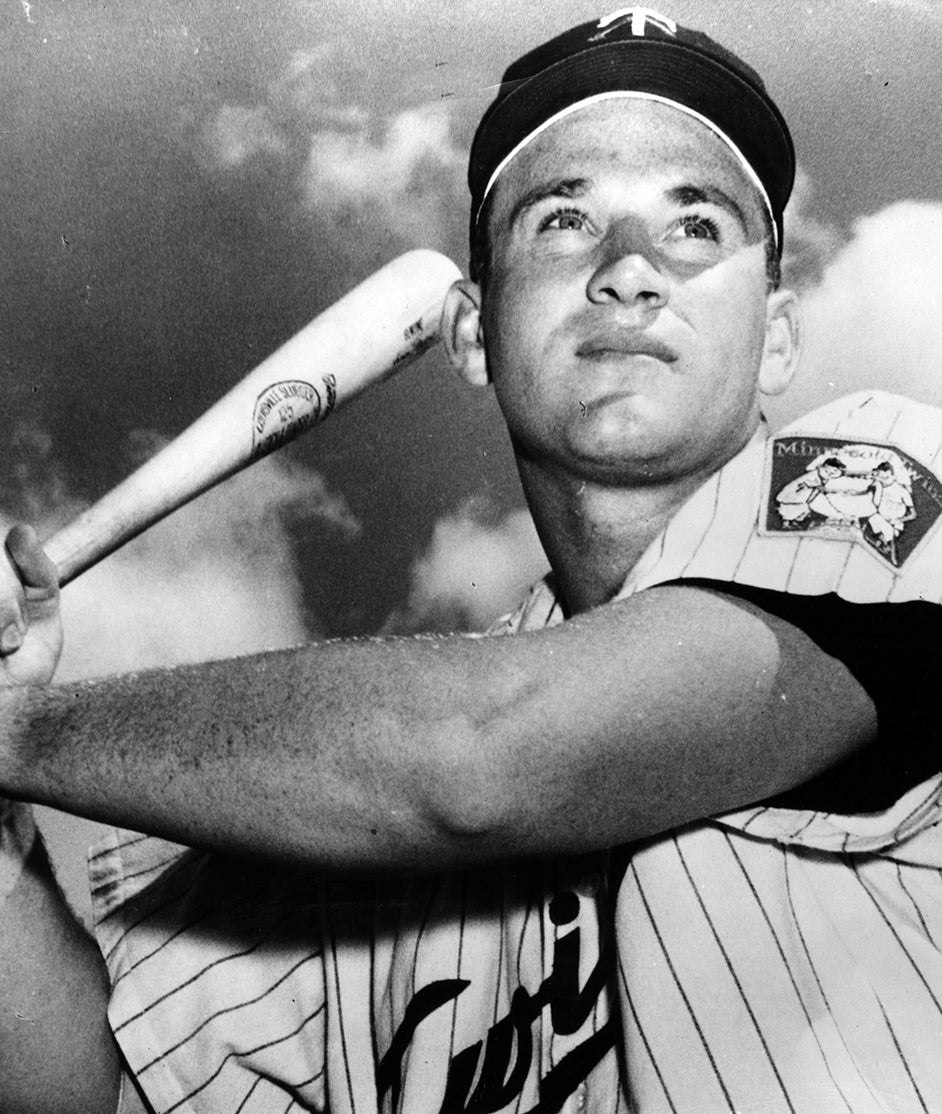

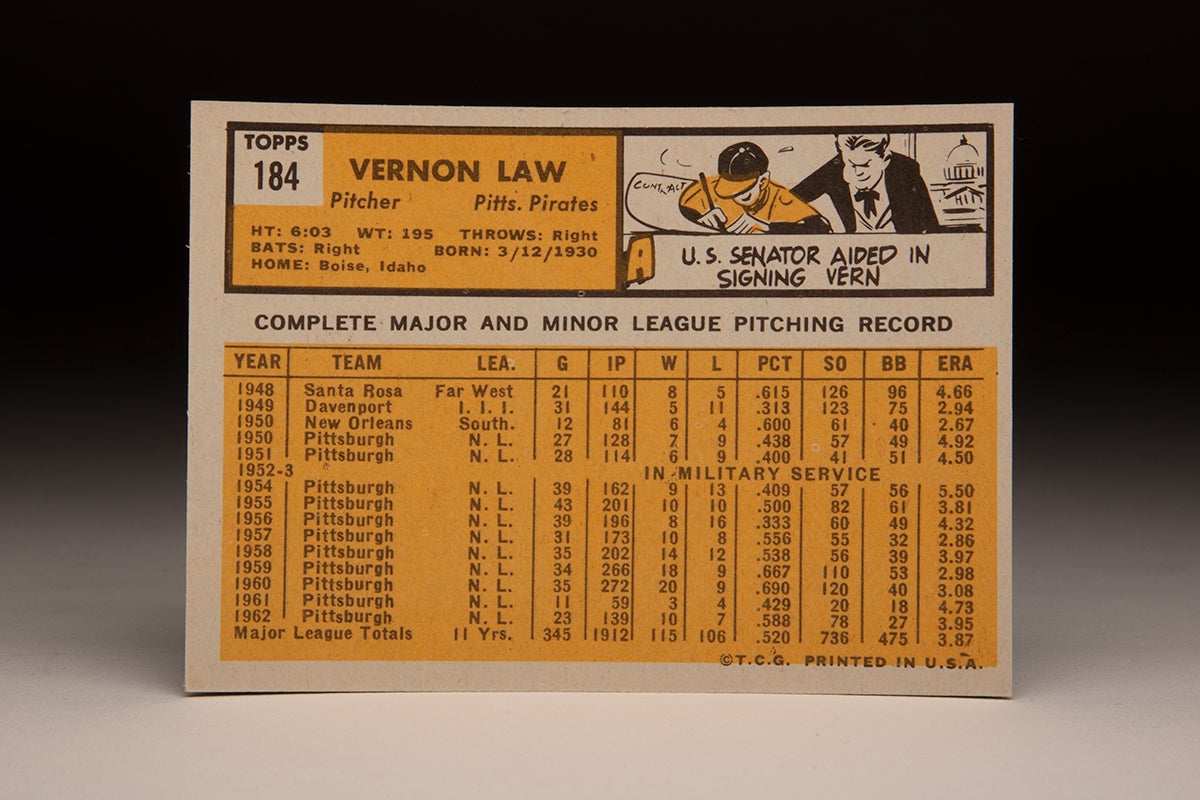

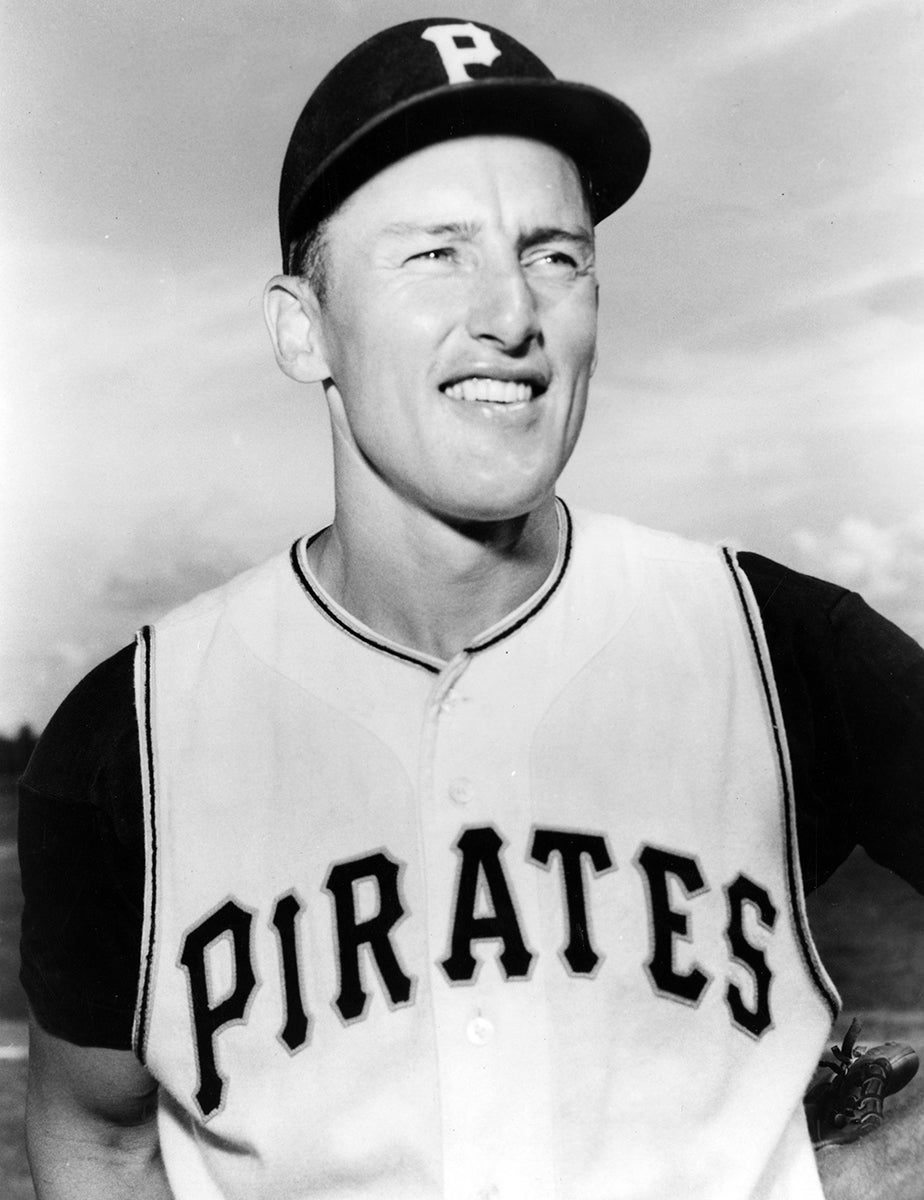

Born Vernon Sanders Law on March 12, 1930, in Meridian, Idaho, Law was one of 10 children. Growing into his 6-foot-3 frame in high school, Law was an all-around athlete who starred as a baseball pitcher and also on the gridiron. Herman Welker, a future United States Senator from Idaho, saw Law as an amateur and alerted his friend, Pirates owner and movie/singing star Bing Crosby. Welker later tipped off the Washington Senators about future Hall of Famer Harmon Killebrew, another Idaho schoolboy star.

With several teams anxious to sign Law, Crosby dispatched former big leaguer Babe Herman to the Law home immediately after Vern’s high school graduation in 1948. Herman arranged for Crosby to call the Law residence during his visit, and Vern’s mother, Melva, answered.

“My mother about fell over in a faint,” Law wrote in a memoir, parts of which were published in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “She couldn’t believe she was talking to the great singer, Bing.”

Law signed with the Pirates after the team promised an all-expenses paid trip to the World Series for the family if the Pirates ever made it, a $2,000 bonus for Vern and a contract worth another $2,000 for his older brother and catcher, Evan.

Sent to Santa Rosa of the Class D Far West League, Law went 8-5 with a 4.66 ERA in 110 innings. He pitched for Class B Davenport of the Three-I League in 1949, where his 5-11 record masked underlying solid stats like a 2.94 ERA and 123 strikeouts in 144 innings.

The Pirates moved Law up to Double-A New Orleans to begin the 1950 season, and after posting a 6-4 mark with a 2.67 ERA in 12 games he was summoned to Pittsburgh. On June 11, he made his big league debut against the Phillies, going the distance in a 7-6 loss in a game started by future Hall of Famer Robin Roberts of Philadelphia and won by the eventual National League Most Valuable Player, Jim Konstanty.

“My mouth fell a mile when (Hal) Luby, the New Orleans manager, called me into his office and told me they wanted me in Pittsburgh,” Law told the Idaho Statesman after the 1950 season. “I was surprised, to say the least.”

Law picked up his first career victory on July 7 against the Cardinals and finished the season with a 7-9 record and 4.92 ERA. He reported to Spring Training in 1951 with high expectations, but a sore arm limited his effectiveness. He finished the year with a 6-9 mark and 4.50 ERA in 114 innings – with half of his 28 appearances coming out of the bullpen.

“I don’t think there was a time during the season that the arm didn’t trouble me,” Law told the Quad-City Times in November of 1951. “A doctor in Meridian told me that it might have been the result of a shoulder injury I suffered in football in my senior year. I cracked up a bit once.”

Law, however, was about to get an unexpected rest for his arm. Classified 3-A for the military draft after he married his high school sweetheart VaNita McGuire on March 3, 1950, Law thought he might avoid being selected but saw the writing on the wall as the Korean War dragged on. Following the 1951 season, Law drove from Meridian to Fort Eustis, Va., to enlist in the Army.

“Millions of others have gone,” Law told the Quad-City Times. “It is my turn to go, and I am not kicking.”

Law spent the next two seasons in the military, playing ball and displaying his prowess as a hitter. When he was discharged in late 1953, Branch Rickey – who became the Pirates’ general manager following the 1950 season – offered the opinion that Law might be moved off the mound and into a position player role.

But Law remained a mainstay on the Pirates’ staff, working 161.2 innings for a Pittsburgh team that lost 101 games. Law finished the year with a 9-13 record and 5.51 ERA but drew considerable interest from other teams prior to the June trade deadline.

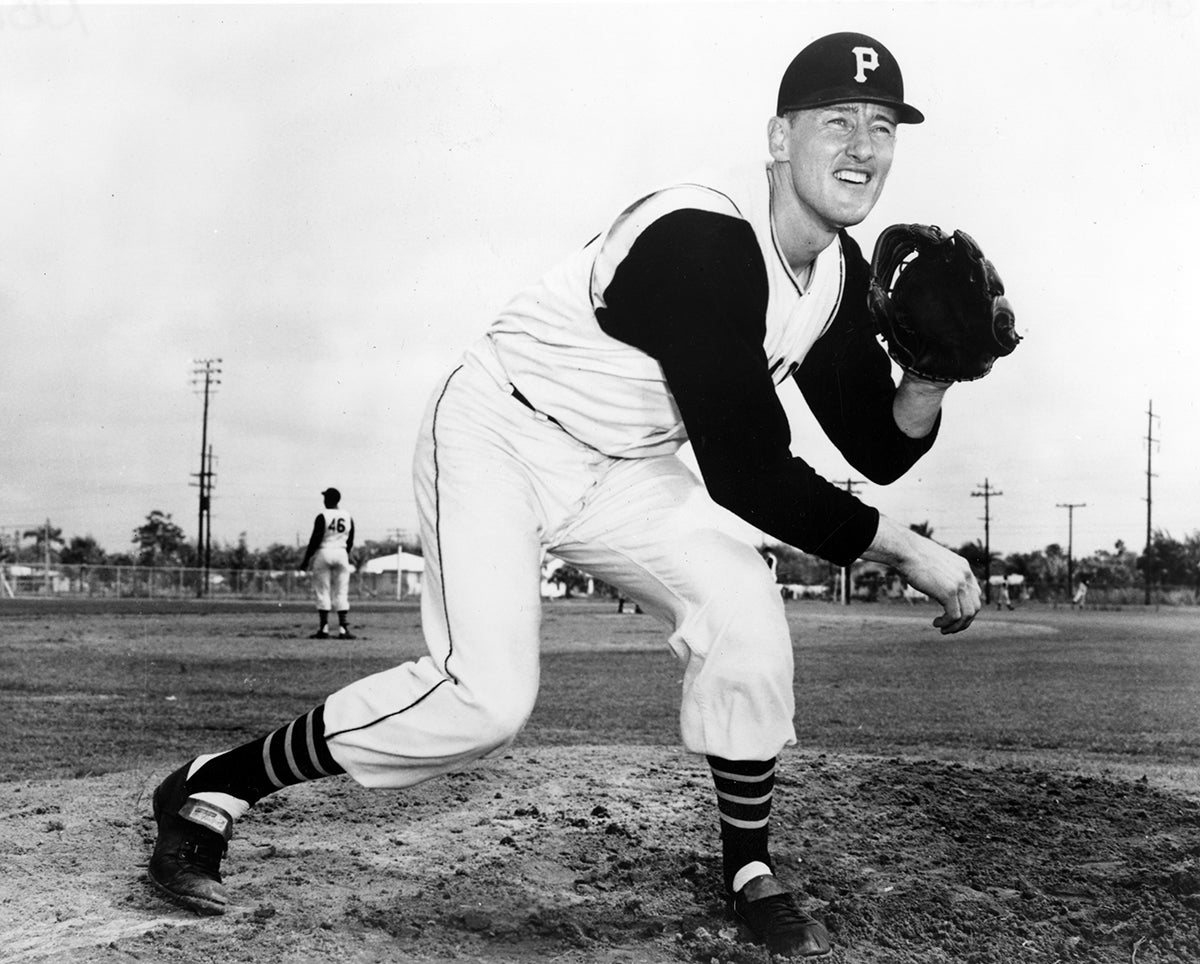

In 1955, Pirates manager Fred Haney moved Law in and out of the rotation, working him 200.2 innings in a swingman role. Law finished the year 10-10 with a 3.81 ERA and even drew a down-ballot vote in the NL Most Valuable Player race. That vote may have been the result of one game – a July 19 start against the Braves at Forbes Field where Law worked 18 innings but got a no-decision when the Pirates pushed two runs across the plate in the 19th after Milwaukee broke the 2-2 in the top of the inning on an RBI single by future Pittsburgh manager Chuck Tanner.

Since then, no pitcher has worked 18 innings in one game. Since 1930, only two other pitchers have gone at least 18 innings in a single game: Les Mueller of the Tigers with 19.2 innings against the Athletics on July 21, 1945; and future Hall of Famer Carl Hubbell of the Giants, who worked 18 shutout innings in a 1-0 win over the Cardinals on July 2, 1933.

Remarkably, Law made his next scheduled start five days later and pitched 10 innings in a 3-2 win over the Cubs. But in each of his next three starts, Law could not advance past the third inning.

Law suffered an ankle injury sliding during Spring Training the following year and never seemed to get untracked in 1956, finishing 8-16 with a 4.32 ERA.

“My arm feels stronger this year than it ever has,” Law told the Deseret News and Telegram of Salt Lake City in July. “Maybe I’m unconsciously favoring the ankle.”

In 1957, Law and the Pirates started down the path toward their World Series title. Law had his best season, going 10-8 with a 2.87 ERA over 172.2 innings. He pitched only one game in September after the Giants’ Rubén Gómez hit Law with a pitch behind the left ear on Sept. 3, rupturing Law’s eardrum and ending his season. But by then, the Pirates were playing better baseball after the mid-summer hiring of Danny Murtaugh as manager.

The Pirates topped the .500 mark for the first time in 10 seasons in 1958, and Law went 14-12 with a 3.96 ERA over 202.1 innings. In 1959, Pittsburgh dropped from second place to fourth place but Law had his best season, going 18-9 with a 2.98 ERA over 266 innings, including 20 complete games – nearly matching his total in that category for the previous three seasons combined.

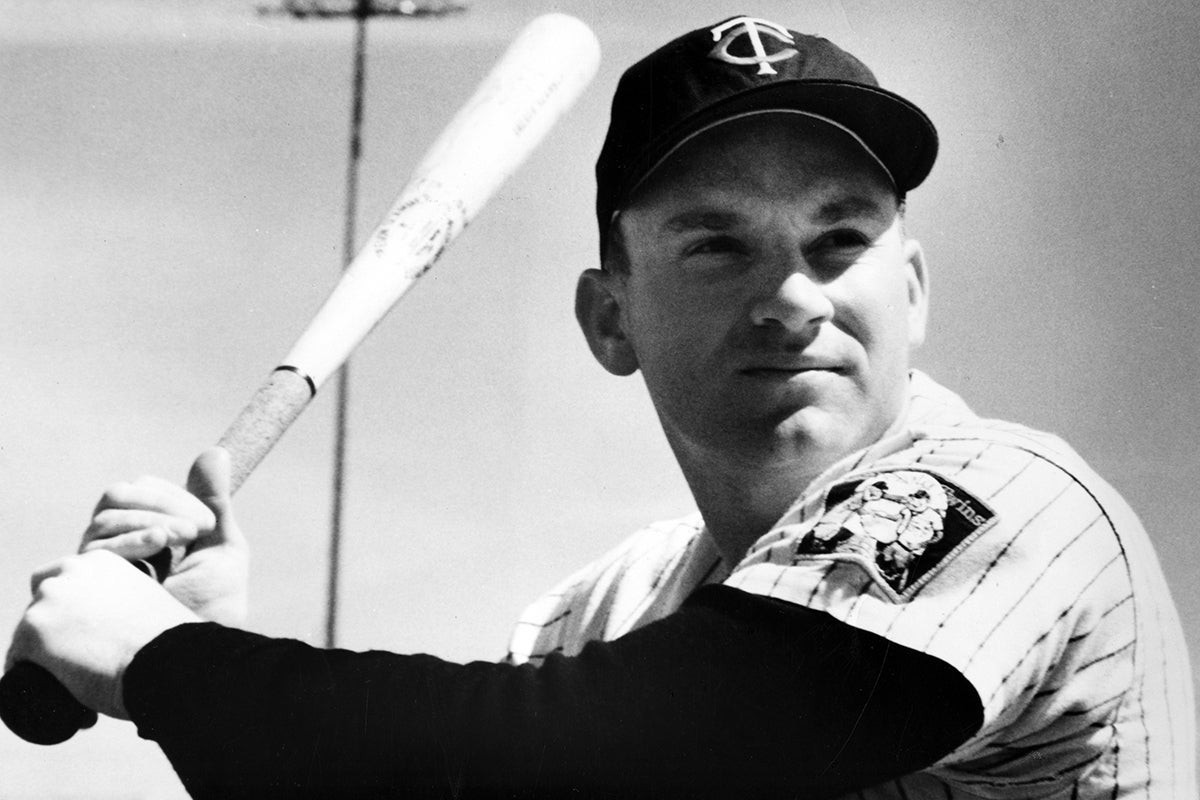

Then in 1960, the Pirates began the season by winning 12 of their first 15 games. Law started the team’s second game of the year and pitched a seven-hit shutout against the Cubs – the first of his four straight complete games to start the season. He worked nine innings in seven of his first eight starts, was 11-4 at the All-Star break (he started the second All-Star Game of that season, earning the win in the NL’s 6-0 win at Yankee Stadium) and won six of his seven starts in August.

The Pirates won the NL pennant by seven games over the runner-up Braves, advancing to their first World Series since 1927. Waiting for them were the Yankees, who had famously swept Pittsburgh in the ’27 Fall Classic behind their Murderers’ Row lineup.

This Yankees lineup wasn’t much different – having blasted 193 home runs thanks to the power of Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris. Law drew the start in Game 1, surrendering 10 hits but just two runs over seven innings as Pittsburgh won 6-4. It marked the first loss in more than two weeks for the Yankees, who finished the regular season with 15 straight victories.

Law was also pitching on a sprained right ankle, injured in a friendly melee during the Pirates’ pennant-clinching celebration. But there was no time for any extra rest as Pirates starters Bob Friend and Vinegar Bend Mizell combined for just 4.1 innings of work in Games 2 and 3 as the Yankees won those contests by a combined score of 26-3.

Taking the mound again in Game 4, Law allowed eight hits and two runs over 6.1 innings – and Roy Face shut down the Yankees with 2.2 scoreless innings to preserve a 3-2 Pirates’ win that evened the series. Pittsburgh then won Game 5 by a score of 5-2 behind the pitching of Harvey Haddix and Face. But the Yankees rebounded to win Game 6 12-0 – putting Law in line to start Game 7.

Pittsburgh led 4-1 after five innings, and Murtaugh’s plan was to get as much out of Law as possible before turning the game over to Face. But in the sixth, Law allowed a leadoff single to Bobby Richardson and then walked Tony Kubek, prompting Murtaugh to call on Face earlier than planned. The strategy backfired when Mantle’s RBI single scored Richardson before Yogi Berra launched a three-run homer, giving New York a 5-4 lead.

“Danny said that this was the greatest decision he’s ever been called on to make,” Law told the Idaho Statesman about Murtaugh’s choice to remove him from Game 7. “I had thought all the time that after I let men get on first and second, Danny felt that with my bad leg I wasn’t able to continue. But I found out from general manager Joe Brown that Danny was afraid I would try to compensate for my bad leg by throwing funny and ruin my arm.

“Of course, when he came out to the mound, I still think he had some doubt about removing me. And I know (Pirates third baseman) Don Hoak helped this along by telling Danny my leg was killing me.”

Face would give up two more runs in the top of the eighth before the Pirates rallied for five runs in the bottom of the frame to take a 9-7 lead. When Friend and Haddix allowed the Yankees to tie the game in the ninth, it set the stage for Mazeroski’s legendary home run that ended the World Series and gave Pittsburgh the title.

Wire stories sent around the country described residents of Law’s hometown of Meridian, Idaho, gathering to listen to their favorite son pitch in the World Series. Many of the dispatches noted Law’s Mormon faith and his “Deacon” nickname, and quickly Law became one of the most famous athletes in the country.

On Nov. 3, Law was named the winner of the Cy Young Award. In an era when only one Cy Young was given for both leagues, Law – who was 20-9 in 1960 with a 3.08 ERA and an MLB-best 18 complete games – received eight first-place votes, twice as many as runner-up Warren Spahn of the Braves.

When Law returned home to Idaho after the season, Governor Robert E. Smylie proclaimed “Vern Law Day” throughout the state. Law spent much of the offseason on the banquet circuit before reporting to Spring Training in 1961. But Law and the Pirates suffered through a miserable season trying to defend their title, with Law making only 11 appearances before shoulder pain ended his season in July. Pittsburgh finished with a record of 75-79.

Law went home during the season to try to regain his strength, and by September doctors told him his shoulder had healed to the point where permanent damage was no longer a threat. But he would not know until the 1962 season if he was able to pitch again.

“We won’t really know much until he has thrown hard for a sustained period of time,” Pirates general manager Joe L. Brown told the Pittsburgh Press.

But Law didn’t make his first appearance in 1962 until April 30, and he went 10-7 with a 3.94 ERA in 139.1 innings. Then in 1963, Law was scuffling with a 4-5 record and 4.93 ERA in August when he decided to retire.

“I feel good, my arm feels good,” Law told the Associated Press. “At the end of the year, I’ll ask for my outright release and if the club gives it to me, I might try to hook on with some other ballclub.”

But when the Pirates offered him a contract for the 1964 season, Law accepted. He worked his way back into the rotation and went 12-13 with a 3.61 ERA over 192 innings.

Then in 1965, Law regained his 1960 form by going 17-9 with a 2.15 ERA in 217.1 innings. He started the season 0-5 before winning his last nine decisions. And though he drew no support in the Cy Young Award race as Sandy Koufax was a unanimous winner, Law did finish 17th in the NL MVP voting and was named United Press International’s Comeback Player of the Year.

“It’s a feather in a man’s cap,” Law told UPI. “But…I believe it takes a collective effort for an individual to receive any honor.”

Law turned 36 prior to the 1966 season, and he was 12-8 that year with a 4.05 ERA in 177.2 innings. The following year, Law was 2-6 with a 4.18 ERA when he decided to retire – this time for good – on Aug. 31, 1967.

“Law was as fine a pitcher in 1960 as I ever saw,” Murtaugh told UPI when Law announced his retirement. “If he hadn’t hurt his arm after that season, I believe we could have won a couple more pennants.”

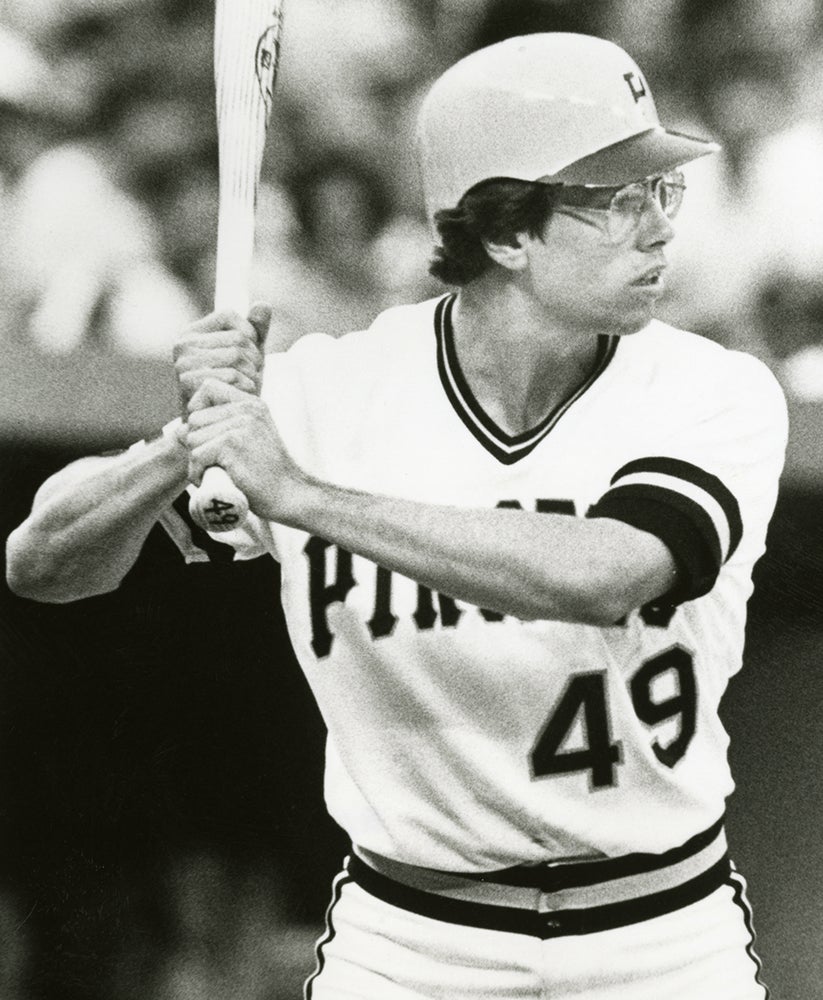

Law served as the Pirates’ pitching coach in 1968 and 1969 before becoming an assistant coach at Brigham Young University and later working in the minor leagues and in Japan. He also managed the Denver Bears – the Triple-A affiliate of the White Sox – during the 1984 season. By then, one of his sons – Vance Law – was a regular infielder with the White Sox. Vance Law enjoyed an 11-year big league career and was named to the 1988 NL All-Star Game with the Cubs.

Vern Law finished his 16-year career with Pittsburgh with a record of 162-147 – a wins total that ranked sixth all-time in club history when he retired and still does. But for many Pirates fans, Law’s career boils down to one season – and three unforgettable starts.

“When a man does something outstanding, he gets honors and awards even though others contributed to it,” Law told UPI in 1965. “That’s the way our society is – and all I can say is that I’m grateful for the honors coming my way.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum