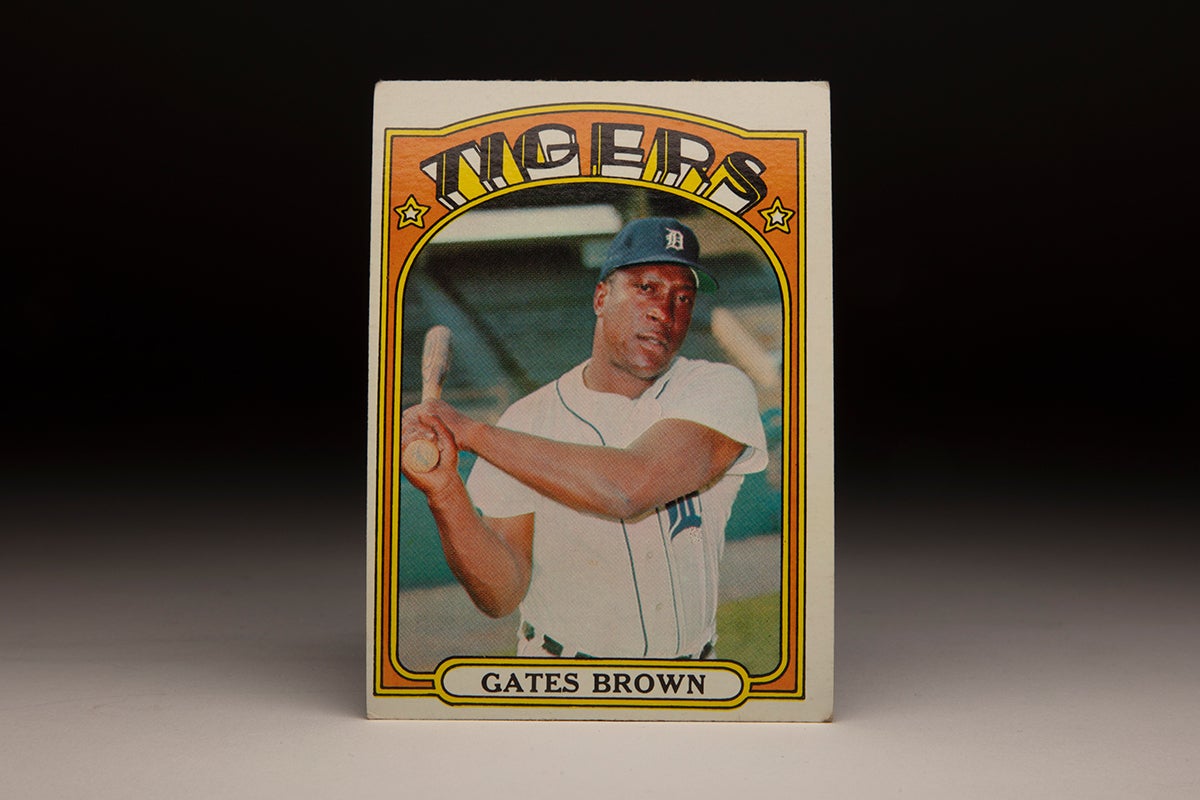

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Gates Brown

In 2009, the town of Crestline, Ohio, named its high school baseball field after Gates Brown, who had grown up there in the 1940s and 50s.

It was an improbable honor for the former Detroit Tigers folk hero, who beat the odds after a prison sentence nearly derailed his athletic career.

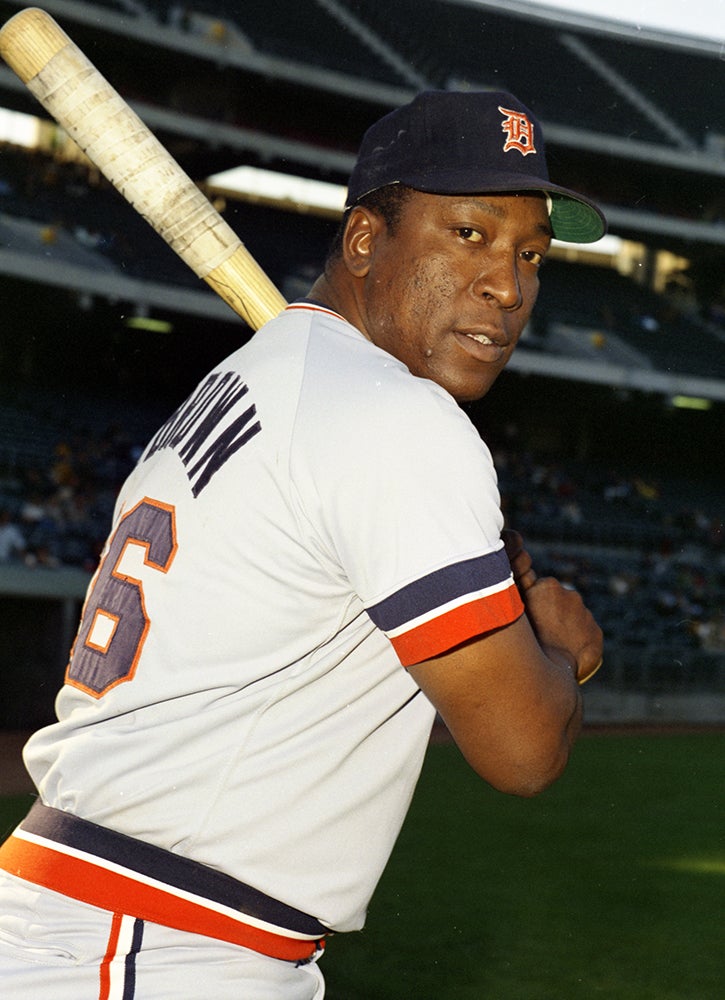

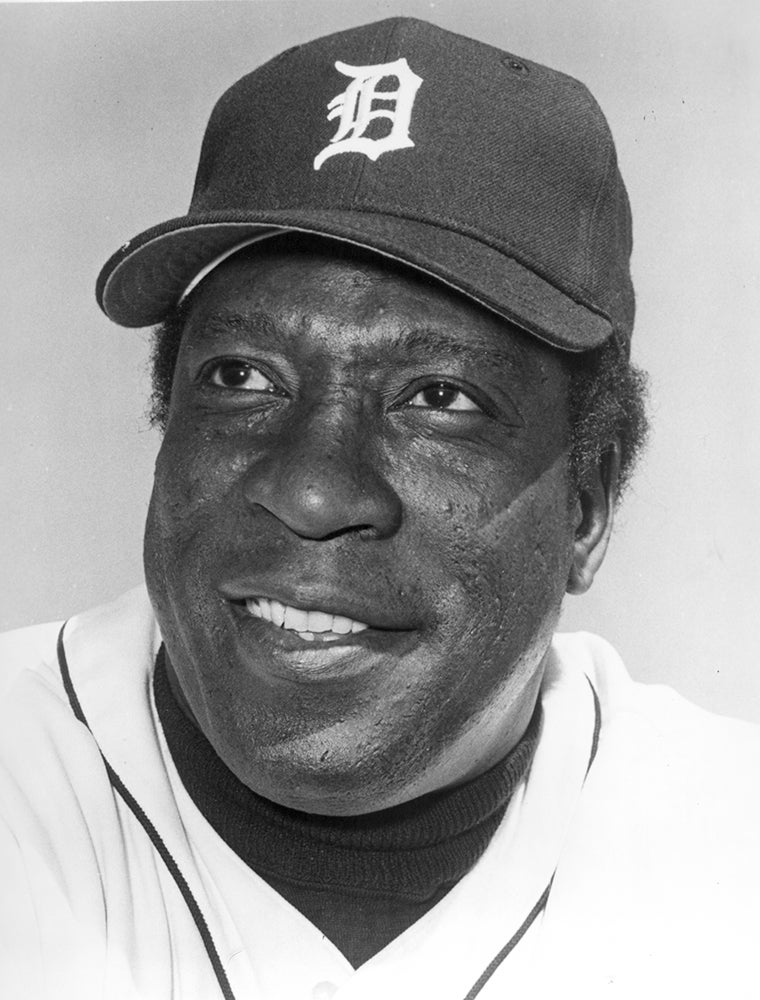

William James Brown was born May 2, 1939, and was given the nickname “Gates” by his mother, Phyllis. He grew into a thick 5-foot-11, 200-pound frame that helped him star as a football player for Crestline High School – where he was recruited by several Big Ten schools as a running back. But before his junior season, Brown found himself on the wrong side of the law and was sent to a juvenile facility in Lancaster, Ohio.

He returned to Crestline High School for his senior year but was barred from participating in sports and was soon arrested for breaking and entering. This time, Brown was sentenced to 22 months at the nearby Mansfield Reformatory, the prison that was used as the site of the 1994 film The Shawshank Redemption.

“People told me to keep the faith, but it was hard – being 17 with nothing in front of you,” Brown told the Mansfield News Journal in 2009. “I was doing hard time and the future didn’t look bright.”

The prison in Mansfield had a reputation for overcrowding and poor conditions, but the prison’s athletic director spotted Brown’s talent as a hitter and wrote letters to several big league teams suggesting they take a look at Brown. In 1958, the Tigers’ scout Pat Mullin – who would later become a Tigers coach while Brown was on the big league roster – signed Brown to a contract that included a $7,000 bonus.

“It wasn’t easy to sign him,” Mullin told the Detroit Free Press. “Two other clubs were after him: The Indians and the White Sox. Even Hoot Evers (Cleveland’s farm director) came down to see him.”

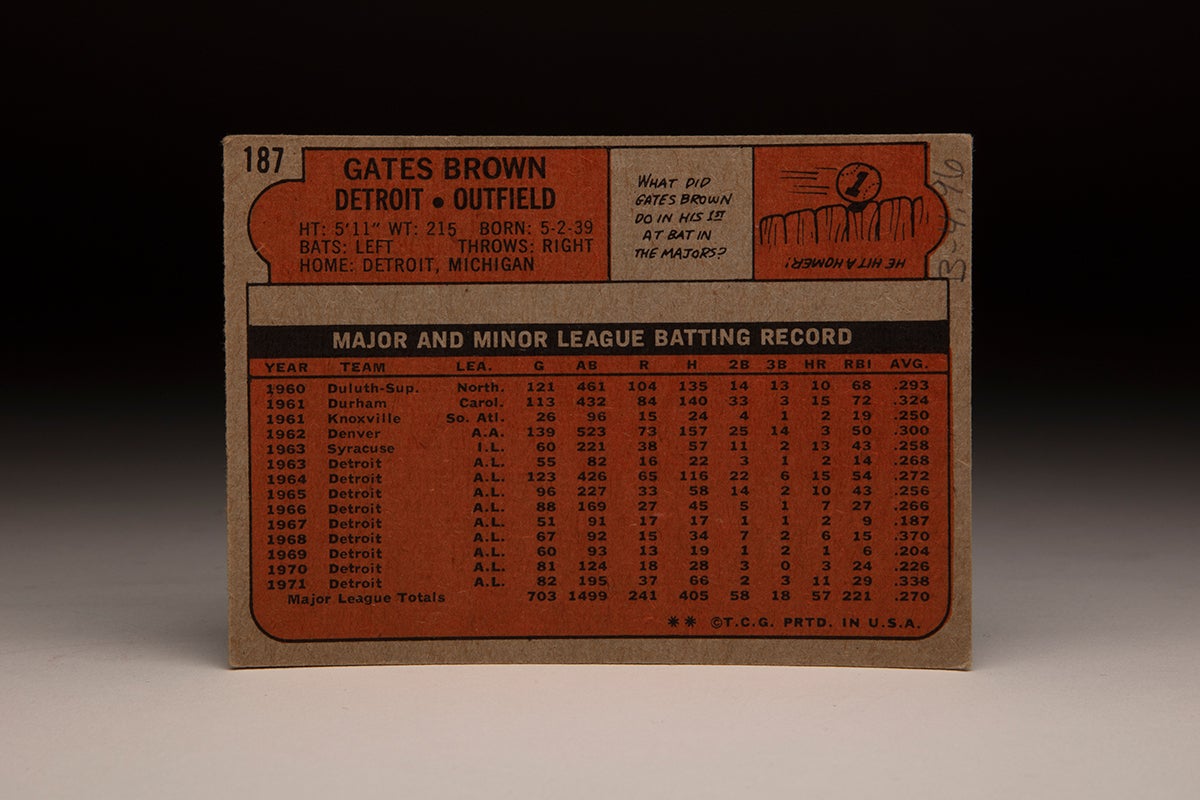

After gaining his release from prison six months early because he had procured a job, Brown debuted professionally with Duluth-Superior of the Class C Northern League in 1960, hitting .293 with 104 runs scored, 10 homers and 68 RBI in 121 games. He spent most of the 1961 season with Class B Durham of the Carolina League, hitting a league-best .324 with 33 steals in 113 games. Advancing to Triple-A in 1962, Brown hit .300 in 139 games for Denver.

After beginning the 1963 season with Triple-A Syracuse, Brown was called up to Detroit. Debuting against the Red Sox as a pinch-hitter on June 19, he homered to deep right field at Fenway Park off Boston’s Bob Heffner.

It would be a fitting debut for a player who would go on to set multiple big league records as a pinch-hitter.

Brown began the 1964 season on the Tigers’ bench but became the team’s starting left fielder in May, finishing the year with a .272 batting average, 15 homers, 54 RBI and 11 steals in 123 games. It would mark the only time he appeared in more than 100 games until the 1972 season.

In 1965, youngster Jim Northrup got the Opening Day start in left field – and by May heralded prospect Willie Horton had claimed the job. Brown, however, kept his spot on the roster with his pinch-hitting skills, batting .256 with 10 homers and 43 RBI in 96 games.

“I don’t mind being used as a pinch-hitter,” Brown told the News Journal in 1966. “You’re generally sent up in a tight situation, and besides, I like to hit with men on base. That’s the only way you make money.”

After hitting .266 in 1966, Brown struggled to find his rhythm in 1967 and was batting .188 when he crashed into the outfield wall at Tiger Stadium while chasing a fly ball on June 29 and dislocated his left wrist. He missed all of July and August before returning in September as the Tigers were in the midst of one of the greatest pennant races in American League history.

Detroit, Boston, Minnesota and Chicago battled down to the final week – and Brown appeared in six games over the season’s final three weeks, all as a pinch-hitter. His final at-bat came in the final game of the season, with Detroit needing a win over the Angels in the second game of a doubleheader to force a one-game playoff against the Red Sox for the pennant.

With Detroit trailing 8-5 with two outs and Dick McAuliffe on first base, Brown pinch hit for Dick Tracewski and flew out to right field against reliever Minnie Rojas, ending what would be the Tigers’ best rally for the rest of the game and giving the pennant to Boston.

But Brown and the Tigers got their revenge on the Red Sox in 1968. In the second game of the season, Brown’s pinch hit home run off Boston relief ace John Wyatt in the bottom of the ninth inning gave Detroit a 4-3 win. Brown had a pinch-hit double off Boston’s Jim Lonborg, the 1967 AL Cy Young Award winner, on June 3, smacked a pinch-hit home run off the Red Sox’s Lee Stange on Aug. 9 and then homered in the 14th inning in the first game of a doubleheader on Aug. 11 – again off Stange – to give Detroit a 5-4 win. Brown would start the second game that day in left field and went 2-for-4 with a walk and an RBI.

“I don’t believe in jinxes or anything like that,” Brown told the Associated Press after the Tigers swept the doubleheader from Boston. “I guess I just like to hit against them. Too bad they are leaving town.”

For the season, Brown hit .370 – in a year when the AL batting average was .230 – helping Detroit win the pennant. He totaled what was then an AL record with 18 pinch hits on the season while hitting .362 off the bench.

Though he came to bat only once in the World Series – flying out against the Cardinals’ Bob Gibson in Game 1 when Gibson set a single-game Fall Classic record with 17 strikeouts – Brown would be forever celebrated in Detroit for helping the Tigers win the World Series.

“I was lucky,” Brown modestly said in Spring Training in 1969. “I’ll be the first one to admit it. I don’t know whether I’ll be able to hit like that again.”

In the spring of 1969, MLB experimented with the designated hitter in exhibition games, with most referring to the new position as a “designated pinch-hitter.” The role seemed perfectly suited for Brown – but he, like others, was slow to warm to the change.

“I have mixed emotions about the rule,” Brown told the Fort Lauderdale News. “It takes away part of the game.”

Brown would not have to worry about the rule change until 1973 when the American League officially adopted the designated hitter. Brown would become the Tigers’ first DH on April 7 of that year, missing out on history when New York’s Ron Blomberg became the first DH to bat in a game the previous day.

Following Detroit’s World Series victory, Brown reported to camp in 1969 overweight and struggled during the season, hitting .204 with a career-low (to that point) six RBI in 60 games.

“I’ve got no one to blame but myself for last season,” Brown told the Free Press in the spring of 1970. “I asked for what I got. I just didn’t take good care of myself over the winter.”

Brown bounced back in 1970 with 24 RBI and 20 walks in 81 games then rediscovered his 1968 form in 1971, hitting .338 with 11 homers and 29 RBI in 82 games. Beloved by his teammates and the press, the player nicknamed “Gator” had firmly established himself as one of the best pinch-hitters in the game’s annals.

“In order to be a good pinch-hitter, you have to have your swing down and you have to be ready to jump on the first good pitch,” Brown told the Fort Lauderdale News in 1969. “But the most important thing is making contact. You have to hit the ball or you haven’t done the job. A pinch-hitter has to realize that he may only get up once in eight games. He can’t afford to strike out. He has to hit the ball somewhere.”

Brown hit .230 with 10 home runs and 31 RBI in 103 games in 1972 as the Tigers won the American League East title under manager Billy Martin. Appearing in his second postseason series, Brown came to bat as a pinch-hitter in three games in the ALCS vs. the Athletics – fouling out in Game 1 vs. Rollie Fingers and popping to second against Blue Moon Odom in Game 2 before finding himself in a middle of a Detroit rally in Game 4.

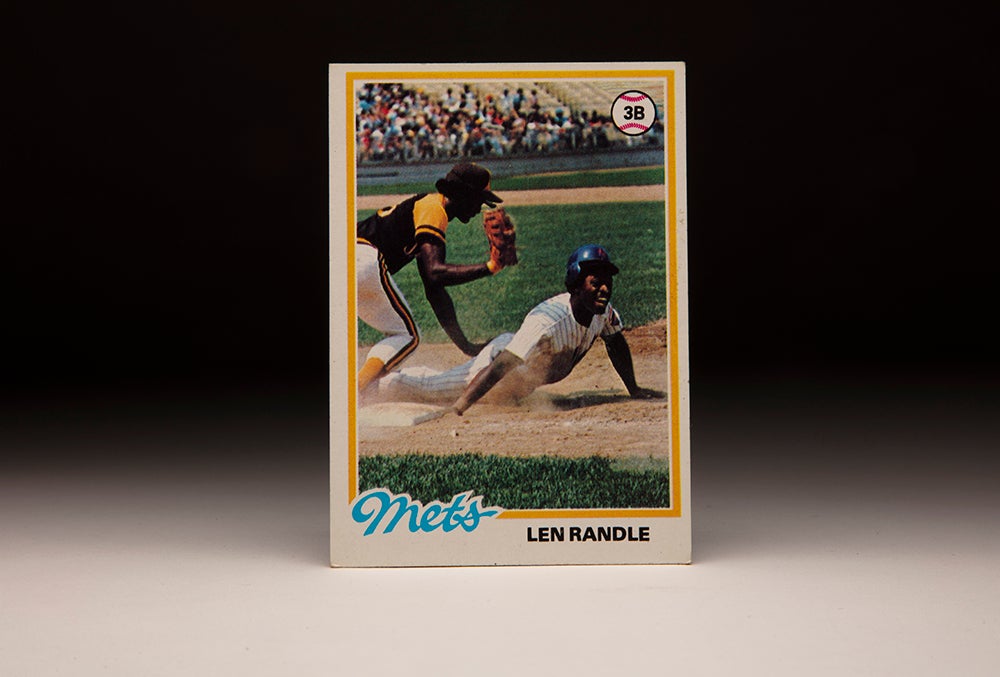

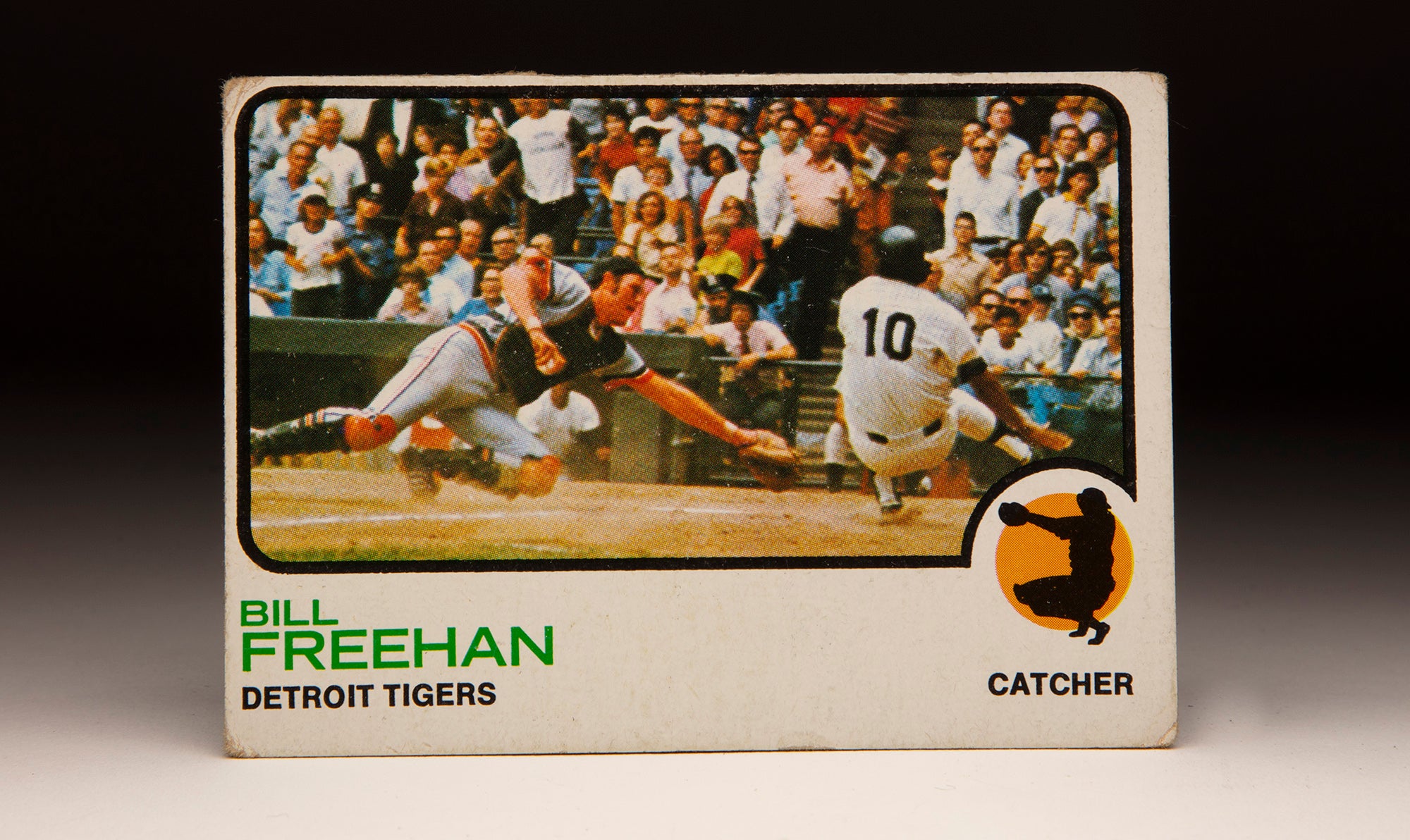

With the Tigers trailing in the game 3-1 entering the bottom of the 10th and down 2-games-to-1 in the best-of-5 series, Brown pinch hit for longtime teammate Mickey Stanley with runners on first and second and no one out. A wild pitch advanced the runners and Brown then walked, loading the bases for Bill Freehan, who grounded to third. But with catcher Gene Tenace playing second base due to Oakland’s tactic of frequently pinch-hitting for its second basemen, the A’s failed to force Brown at second when Tenace was charged with a missed catch error as Brown slid hard into the bag.

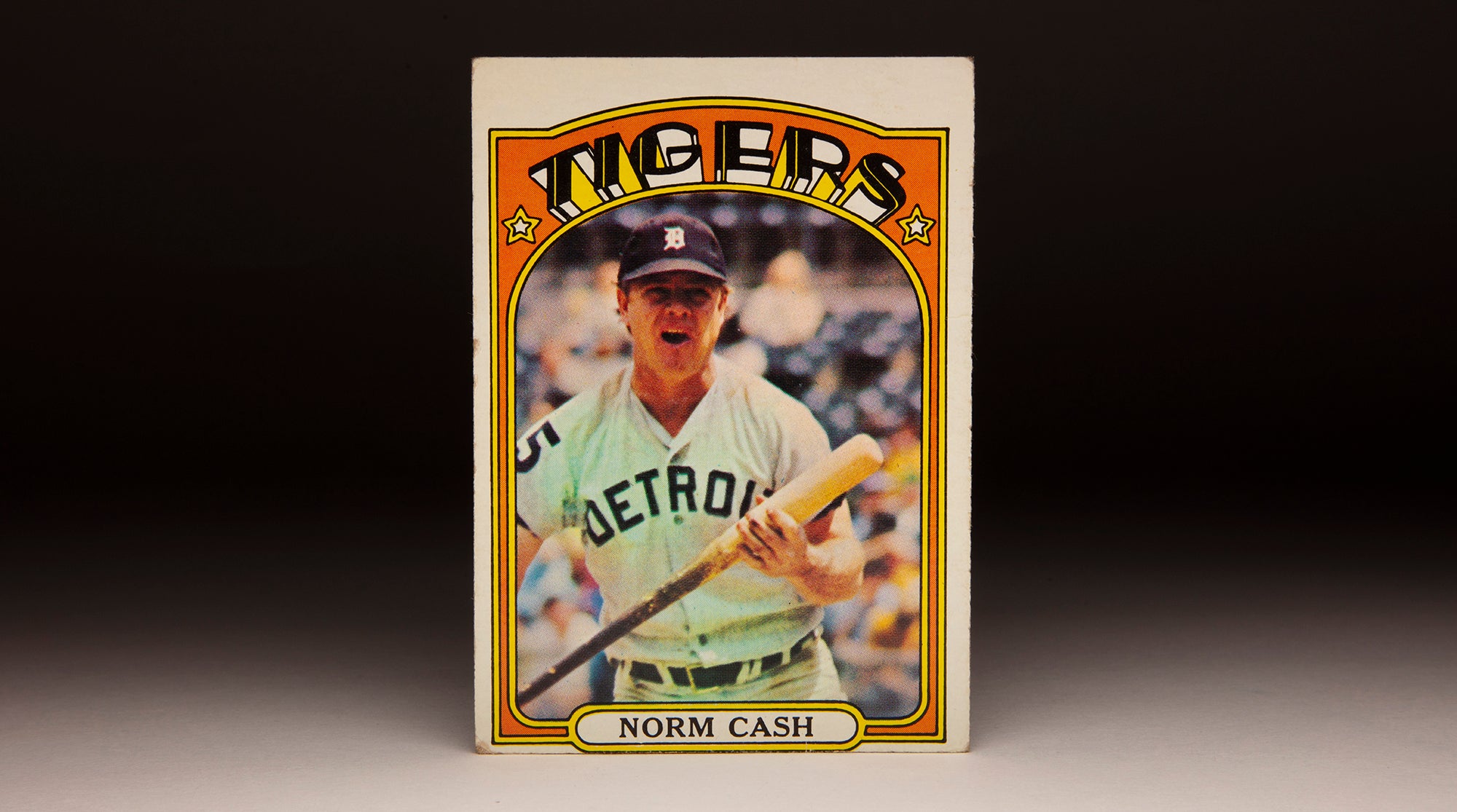

McAuliffe scored on the play to cut Oakland’s lead to 3-2, and Norm Cash followed with a walk to score Al Kaline and tie the game at 3. Northrup then singled to right field to score Brown and win the game.

The A’s, however, won Game 5 to take the series – and Brown was not called upon in that game.

Brown appeared in a career-best 125 games in 1973, including 102 starts as the Tigers’ designated hitter. He batted .236 with 11 doubles, 12 homers and 50 RBI in his age-34 season, drawing 52 walks to boost his on-base percentage to .328. He returned to his pinch-hitting role in 1974 as Al Kaline took over the DH spot during the final season of his Hall of Fame career, with Brown hitting .242 in 73 games.

After hitting .171 in 47 games in 1975 – all coming as a pinch-hitter – Brown announced his retirement two days after the end of the regular season and took a job as a Tigers’ scout. In 1978, Tigers manager Ralph Houk hired Brown as the team’s hitting coach, and he remained a coach (also working as first base coach) under new managers Les Moss and Sparky Anderson, helping Detroit win another World Series title in 1984.

He resigned as hitting coach following the 1984 season after a salary dispute. He did not coach in the big leagues again.

“I consider myself a good coach,” Brown told the AP prior to Spring Training in 1985. “And I always have been.”

Brown retired as the AL leader in pinch-hits (107), pinch-hit homers (16) and pinch-hit RBI (74), and he remains the AL record holder for pinch-hits. In 13 big league seasons – all with the Tigers – Brown hit .257 over 1,051 games, with 18.4 percent of his hits (107 of 582) coming as a pinch-hitter.

He passed away at the age of 74 on Sept. 27, 2013, in Detroit, and was laid to rest in his hometown of Crestline.

With two World Series rings to his credit and a legion of friends in the game, Brown’s career path rates as truly remarkable.

“I got out (of prison),” Brown said in 2009, “and I never looked back.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum