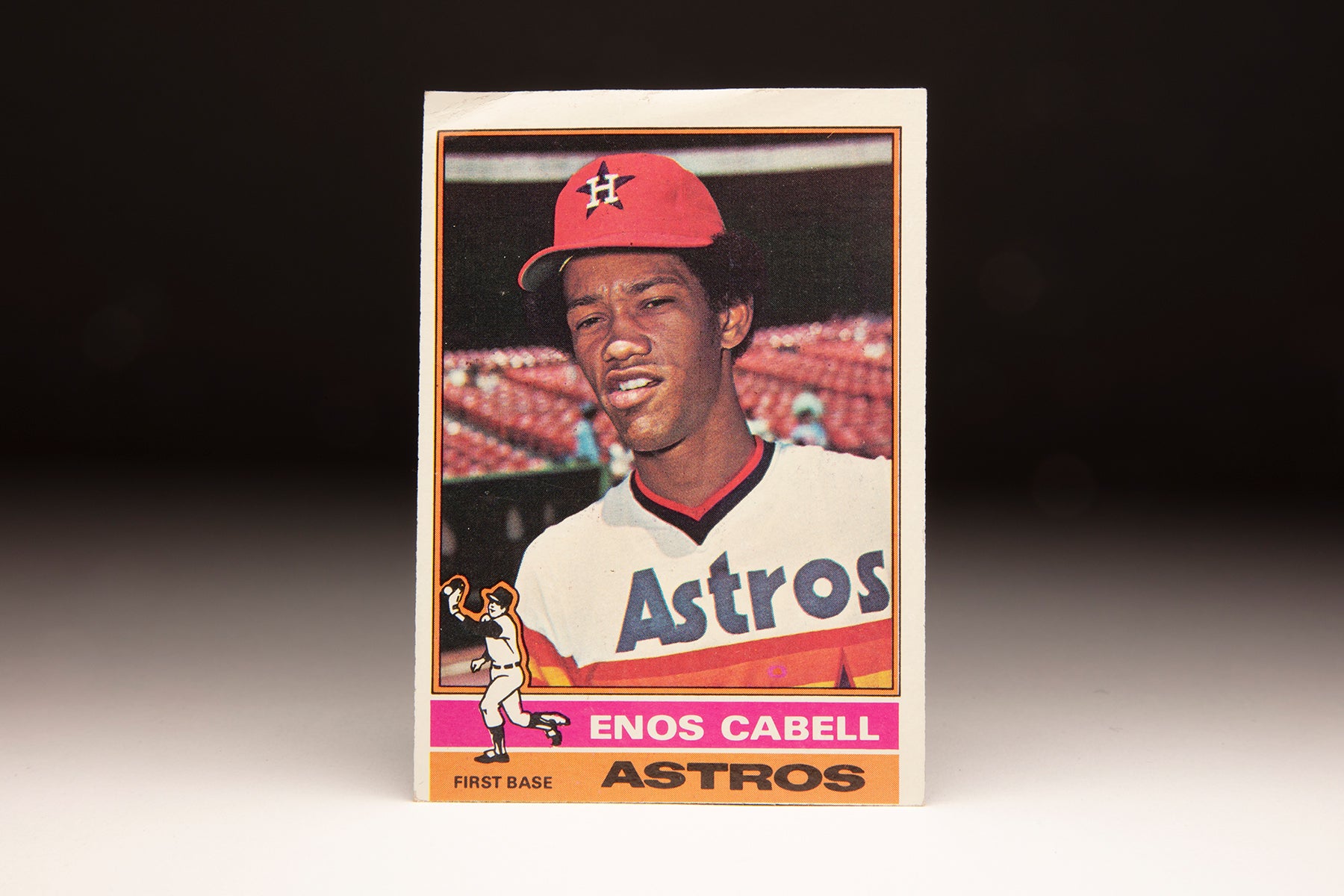

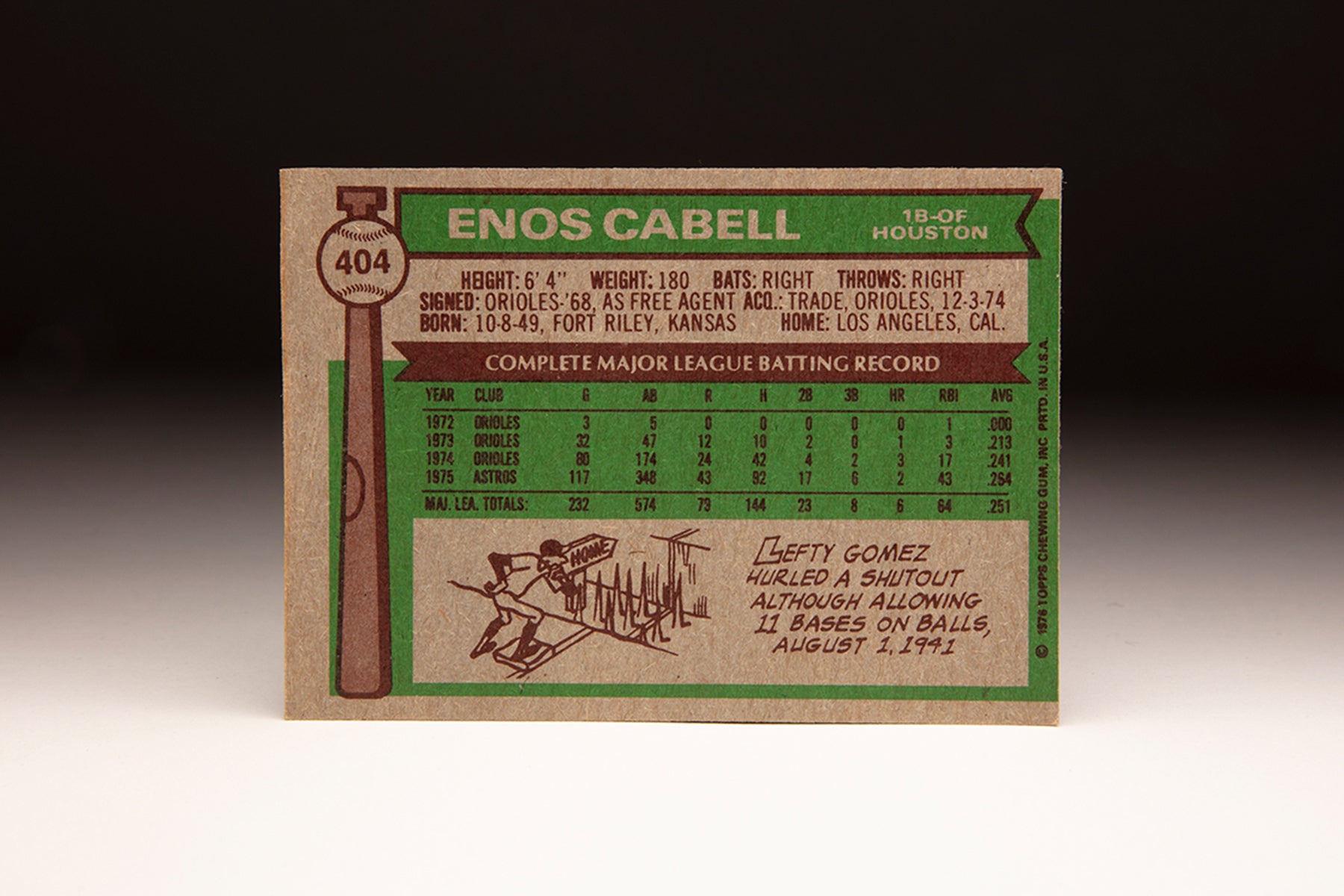

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Enos Cabell

Enos Cabell was part of a young Houston Astros core that stood on the verge of greatness as the 1980s dawned. But by midway through that decade, Cabell was involved in one of the game’s biggest scandals and soon found himself out of baseball.

Redemption, however, would be part of his Astros story in the new century.

Born Oct. 8, 1949, in Fort Riley, Kan., Cabell and his family moved to Gardena, Calif. – halfway between Los Angeles and Long Beach – when he was a child. After graduating from Gardena High School – where he excelled in basketball, earning All-City honors – Cabell enrolled at Los Angeles Harbor College.

After one season where he was named to the all-conference team, Cabell signed with the Orioles as an amateur free agent on Sept. 22, 1968.

Debuting in the pros with Bluefield in 1969, Cabell won the Appalachian League batting title by hitting .374 with 10 homers, 43 RBI and 17 steals in 69 games while posting a .976 OPS. Promoted to Class A Stockton of the California League in 1970, Cabell hit .284 with 10 homers, 67 RBI and 24 steals. Then in 1971, Cabell won his second batting crown by hitting .311 for Dallas-Fort Worth of the Double-A Dixie Association, taking home league Player of the Year honors.

In 1972, Cabell was assigned to Triple-A Rochester, where he hit .269 with eight home runs and 66 RBI. He was ready for a shot at the big leagues, and the Orioles promoted him that September. He appeared in three games without a hit as Baltimore finished five games behind the Tigers in the American League East race. In the winter of 1972-73, Cabell played in Venezuela and hit .372 to win the batting crown.

“He’s got all the signs of being a major leaguer all the way,” Orioles manager Earl Weaver told the News-Pilot of San Pedro, Calif.

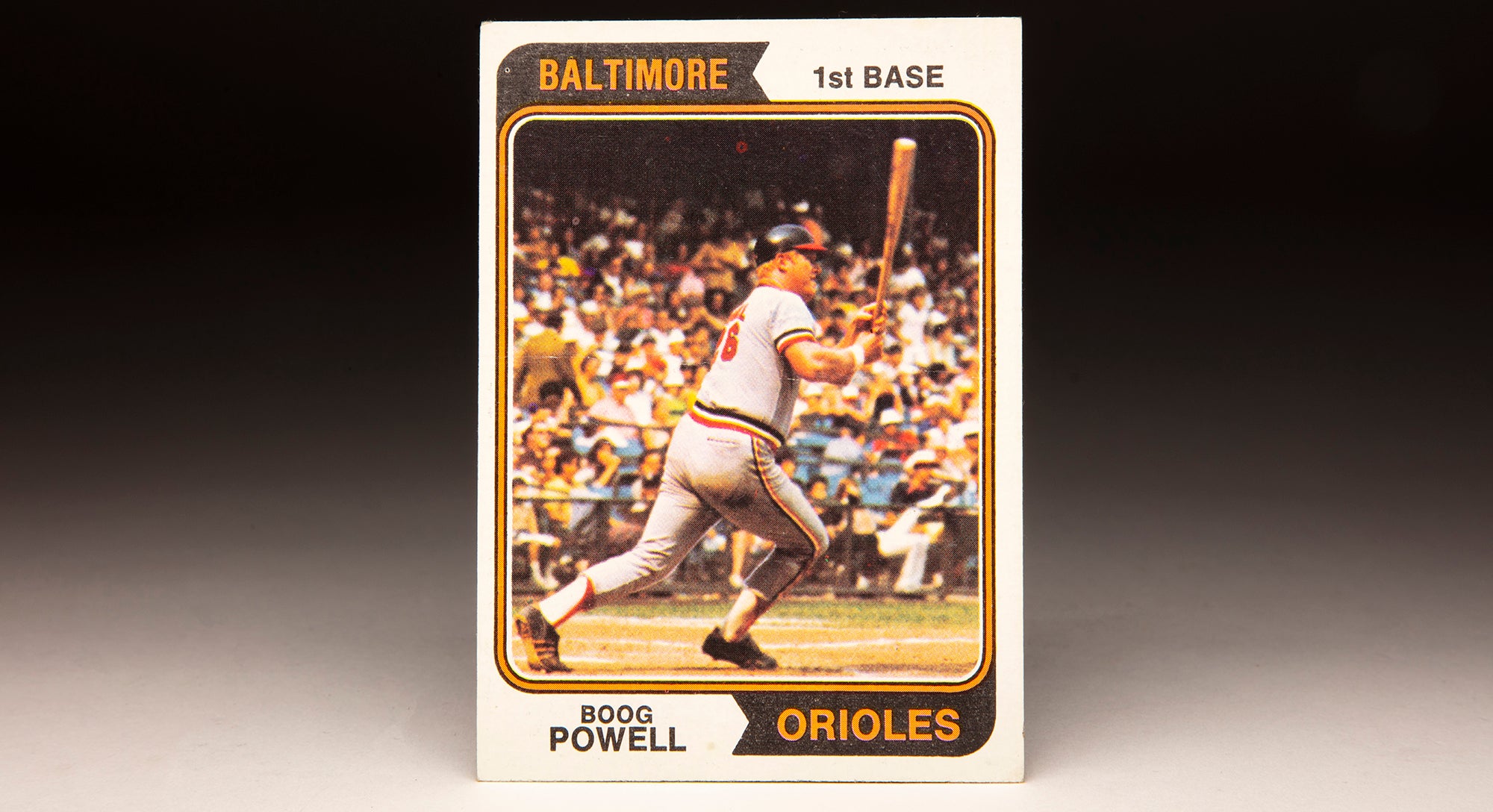

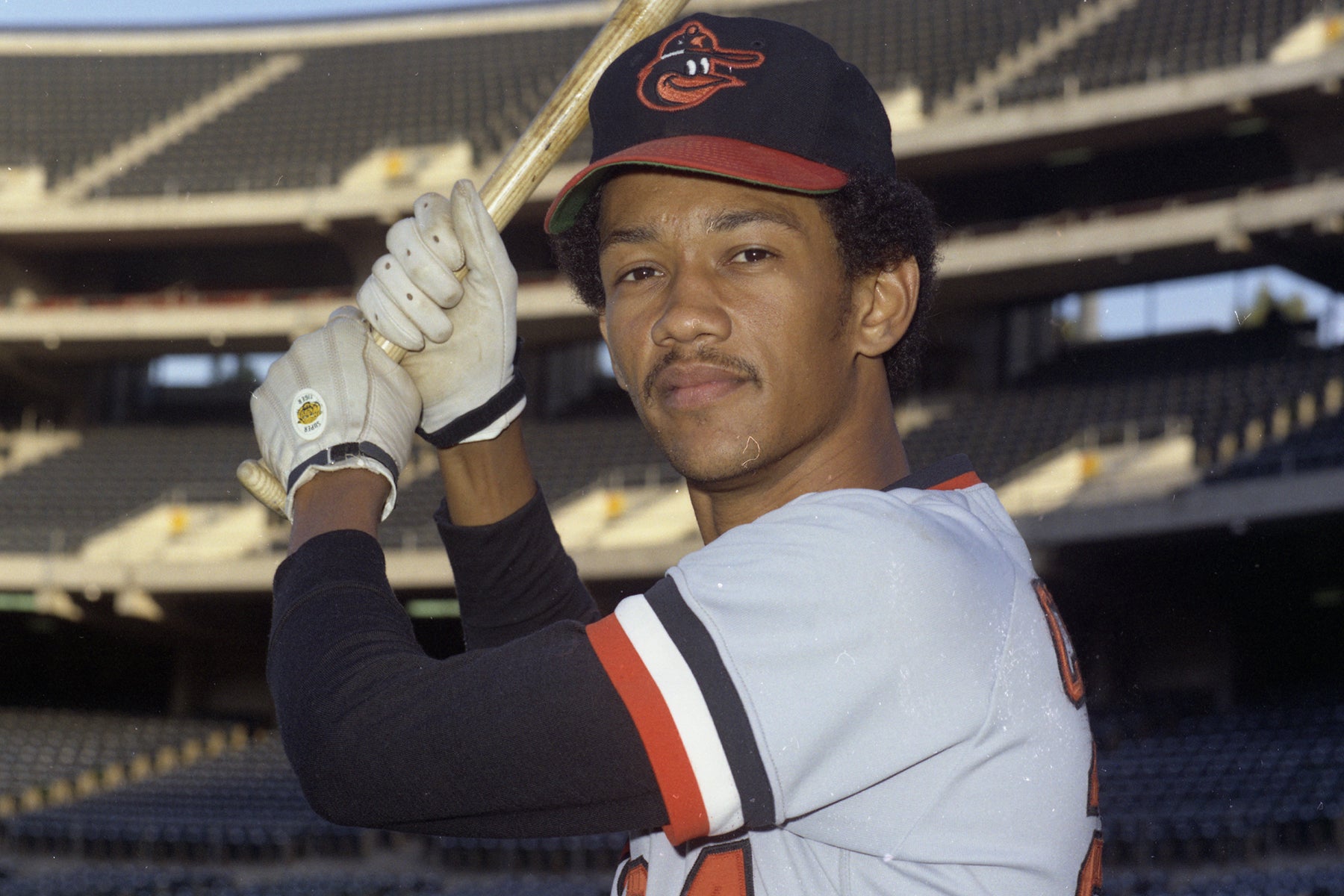

In 1973, Cabell made the Orioles’ Opening Day roster but was sent back to Triple-A after just two games. A natural first baseman, Cabell was blocked by former AL Most Valuable Player Boog Powell at first base and had bench competition from several players in a deep Orioles farm system.

“As long as Boog Powell plays, I don’t have much chance,” Cabell told the News-Pilot. “It’s discouraging to want to play and not get the chance.”

Cabell spent much of the 1973 season with Rochester, hitting .354 in 60 games. He also played in 32 games with the Orioles, batting .213. In 1974, Cabell earned a bench job with the Orioles and he appeared in 80 games, hitting .241 as the Orioles won the AL East title for the fifth time in six seasons.

“You’ve got to have a guy like Enos who can play almost anywhere,” Weaver told the Morning News of Wilmington, Del., in Spring Training of 1974. “Even though you don’t know when you’re going to use him or where.”

Cabell spent the whole 1974 season in the majors and even appeared in three games in the ALCS vs. Oakland, recording one hit in four at-bats. But Cabell was still irked by his lack of playing time and asked for a trade.

“I’d consider it a break if I got traded,” Cabell told the News-Pilot. “There are teams that can use me and Baltimore apparently can’t in the way they’re set up now.”

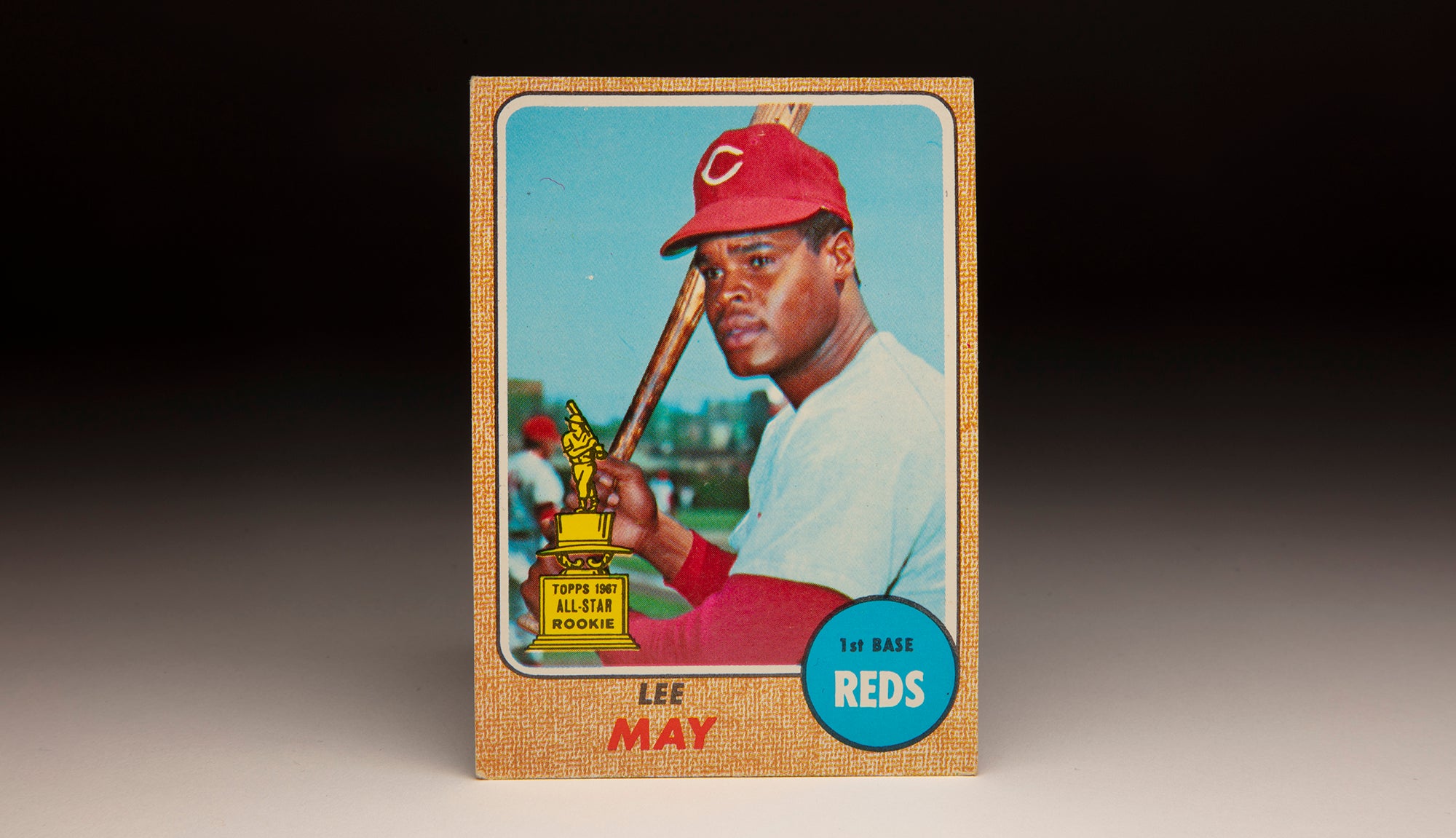

On Dec. 3, 1974, Cabell got his wish as the Orioles sent him and second baseman Rob Andrews to the Astros in exchange for Lee May and Jay Schlueter.

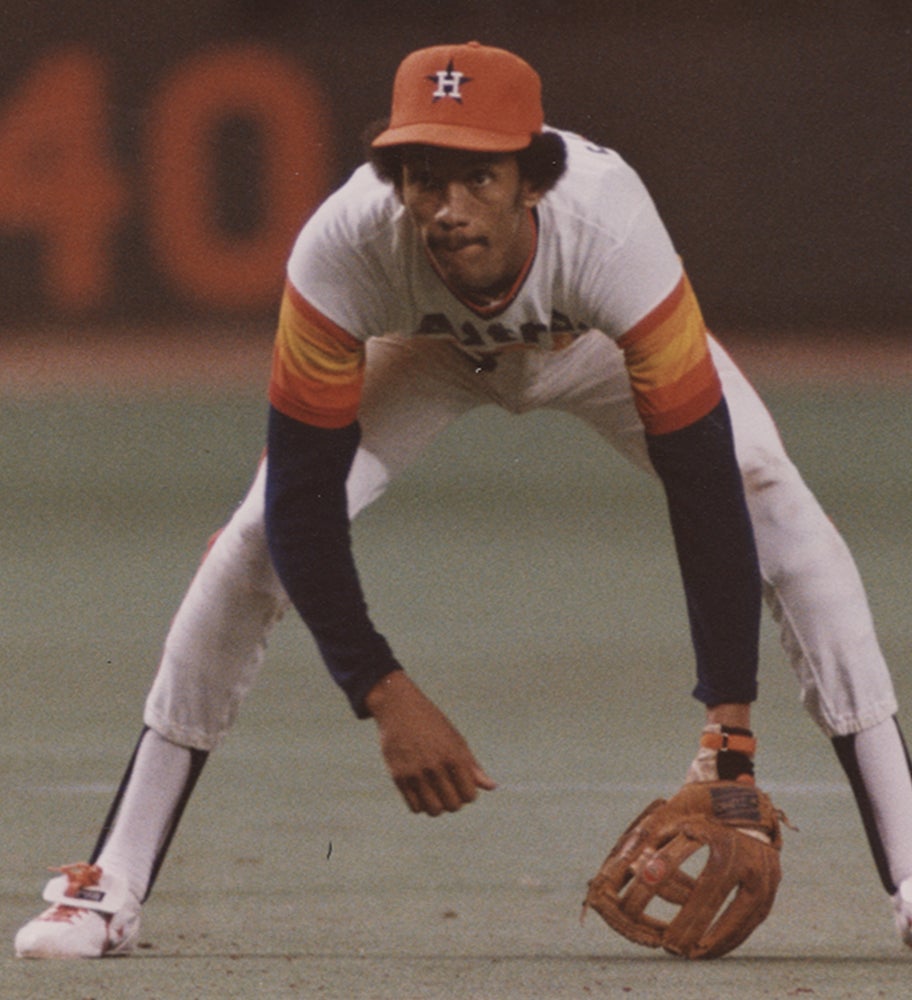

After playing mostly first base throughout his time in the Orioles system, Cabell was moved to the outfield by the Astros and started in left field on Opening Day in 1975. Originally signed as an outfielder, Cabell bounced between left field, right field and first base for much of the season before finding himself at third base in September. For the season, Cabell batted .264 with 43 RBI and 12 steals in 117 games.

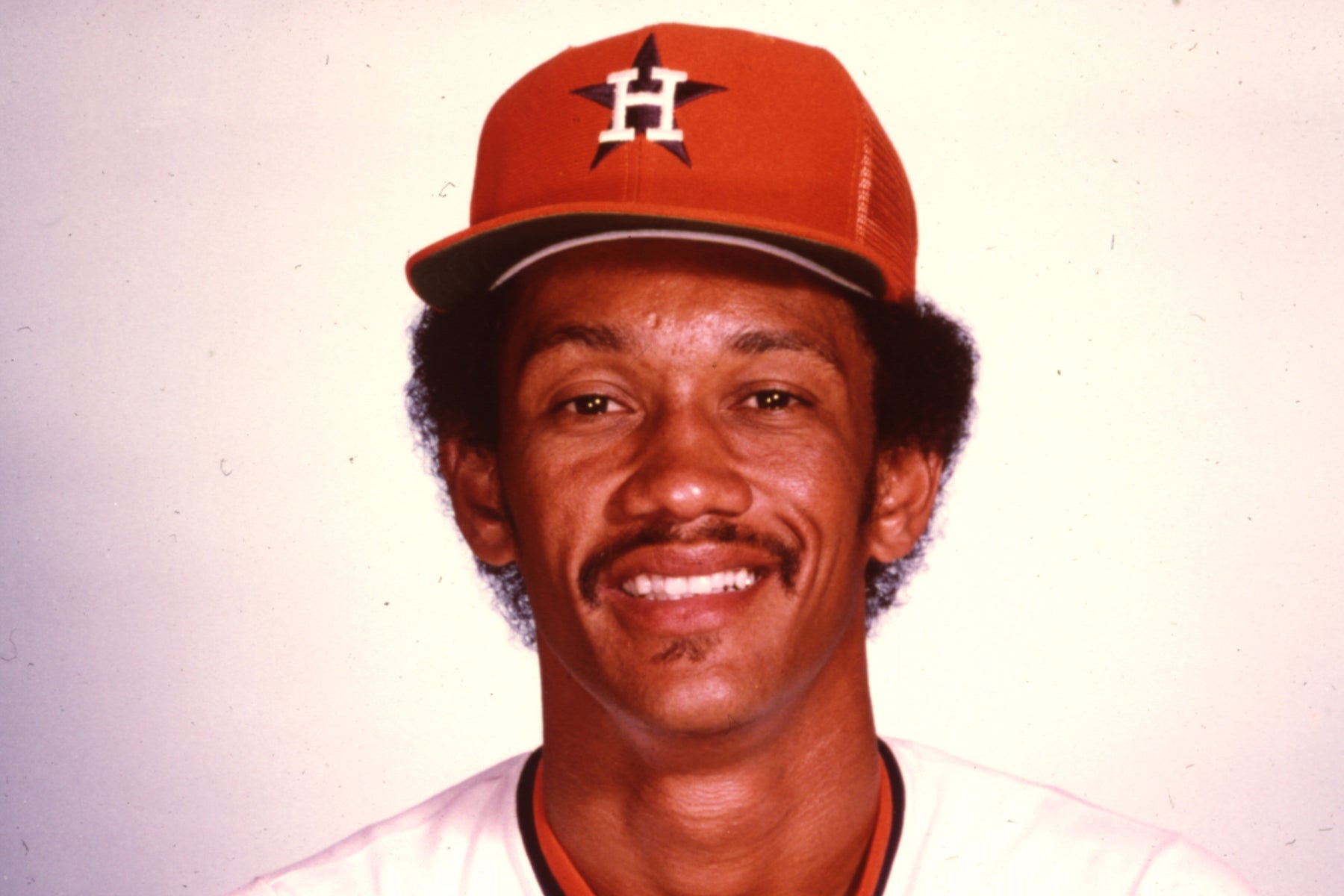

Then in 1976, Cabell was Houston’s Opening Day third baseman and began the year on a blistering pace, recording hits in 14 of the team’s first 15 games to place himself among the league leaders in batting. A viral infection sidelined him for 10 games in mid-May but Cabell continued to hit when he returned, finishing the season with a .273 average, 85 runs scored and 35 steals in 144 games.

“I think I can hit .300,” Cabell told the Daily Breeze of Torrance, Calif. “And I really want to do a good job fielding. Then I’ll be around a long time in this organization.”

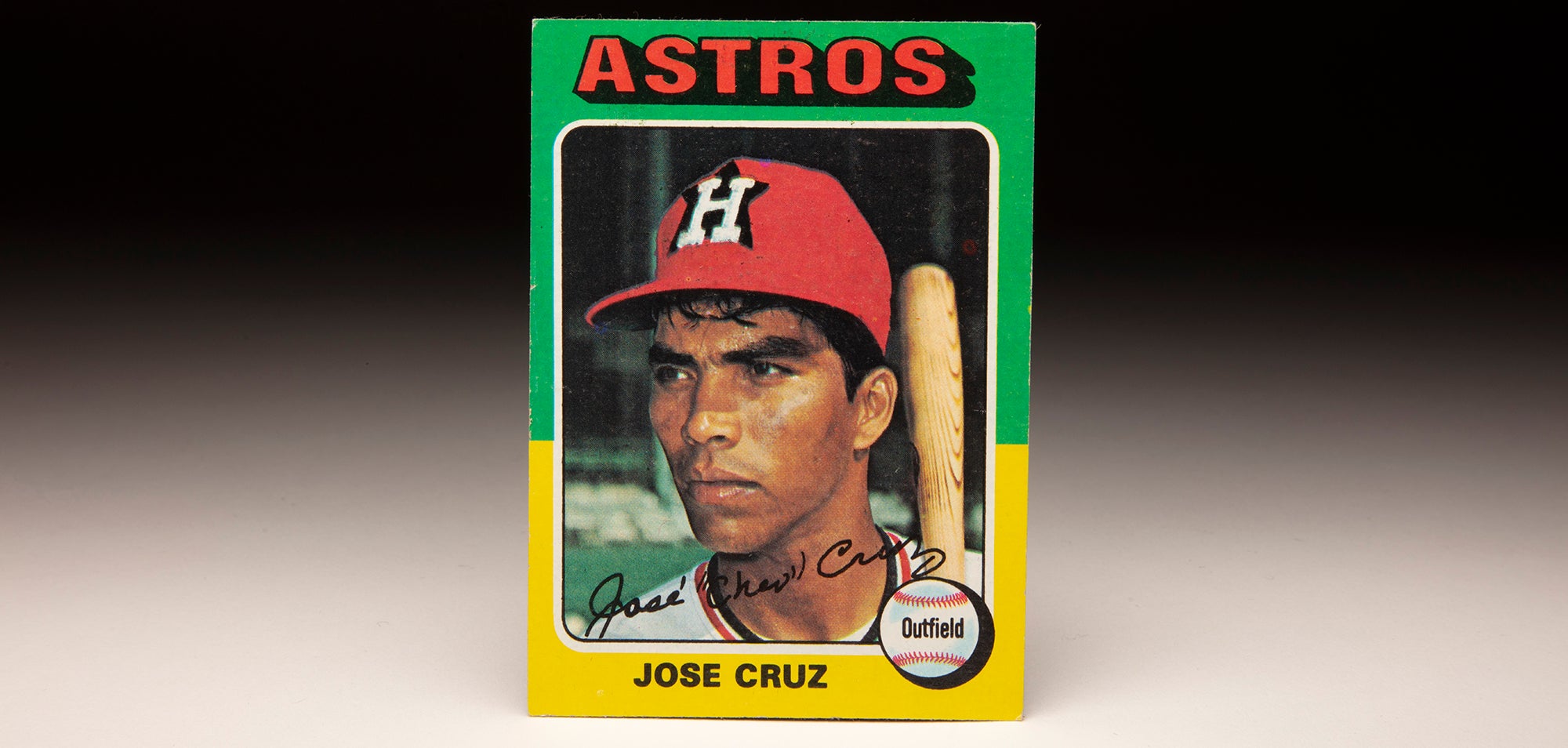

Cabell was part of an Astros’ core that featured position players Bob Watson, José Cruz and César Cedeño along with pitchers J.R. Richard, Joe Niekro and Joaquín Andújar. In 1977, the Astros – who had lost 97 games just two years before – went 81-81 as Cabell hit .282 with 16 home runs, 68 RBI, 101 runs scored and 42 steals.

Cabell was even better in 1978, hitting .295 with 71 RBI, 33 steals and a then-team record 195 hits while playing in 162 games and leading the NL with 660 at-bats. He finished 22nd in the NL Most Valuable Player voting – the only Houston player who received a vote. In early August, Cabell agreed to a five-year contract that with incentives was worth a reported $1 million.

Many experts tabbed the Astros as one of the favorites in the NL West in 1979, and Houston won the most games in franchise history that year – finishing 89-73, just a game-and-a-half behind first-place Cincinnati. Cabell hit .272 with 67 RBI and 37 steals. Cabell and the Astros showed their passion during a July 28 game at the Astrodome where Cabell ignited a brawl after being hit by a pitch by the Dodgers’ Ken Brett.

“I’ve never been a Dodger fan,” Cabell told the Daily Breeze after the brawl. “Even as a kid, I didn’t like them. I was a Giants fan.

“Maybe it has something to do with the fact that in my time in the majors they’ve always been on top. You know, I don’t like the Cincinnati Reds, either.”

The Astros went all-in for the 1980 season, adding future Hall of Famer Nolan Ryan to the pitching staff via free agency. The move paid off as the Astros and Dodgers battled for the division title the whole season, with the teams finishing in a tie at 92-70. In the one-game playoff on Monday, Oct. 6, in Los Angeles, Cabell went 2-for-4 with a walk and two runs scored – plating the game’s second run in the first inning after singling and stealing second base. Cabell scored again in the fourth inning to give Houston a 7-0 lead that became a 7-1 win.

Cabell completed the season with a .276 batting average, 55 RBI and 21 stolen bases. He also led NL third basemen in errors with 29, the second time in four seasons he finished atop that list. In the NLCS vs. the Phillies, Cabell hit a respectable .238 but had no RBI, eliciting criticisms of his performance in the clutch.

On Dec. 8, 1980, the Astros sent Cabell to the Giants in exchange for pitcher Bob Knepper and outfielder Chris Bourjos.

“I’m not surprised (by) what happened,” Cabell told the San Francisco Examiner. “I thought I might be traded.

“I think the Giants are better than Houston was when I got there. I’ve always hit well in Candlestick (Park). I just want to play and win.”

Cabell played in 96 games in 1981, mostly at first base. He hit .255 with 41 runs scored and 36 RBI as the Giants went 56-55 in that strike-shortened season. Then as Spring Training was getting underway, the Giants traded Cabell to the Tigers on March 4, 1982, in a deal for outfielder Champ Summers.

“We just balanced our ballclub,” Tigers manager Sparky Anderson told the Associated Press, referring to the many left-handed hitters employed by Detroit.

Cabell’s right-handed bat fit in with Anderson’s desire for platoon advantages, and Cabell hit .261 with 45 runs scored and 15 steals that year. Then – after rumors swirled that the Tigers would not pursue Cabell following the expiration of his five-year contract – Detroit brought Cabell back for 1983 on a one-year deal worth a reported $275,000.

That year, Cabell hit .311 with 23 doubles, 62 runs scored and 46 RBI as part of a first base platoon with lefty-hitting Rick Leach. He also batted .333 as a pinch-hitter. In higher demand in free agency after that campaign, Cabell returned to Houston and signed a three-year deal worth a reported $1.5 million on Feb. 20, 1984.

“I like Enos Cabell,” Astros owner John McMullen told the Cincinnati Enquirer. “He’s a positive force.”

Cabell, meanwhile, embraced the homecoming.

“I really wanted to stay with Detroit,” Cabell told the News-Pilot. “I wanted to sign with them before the season was over but they wanted to wait. I think after Detroit signed Darrell Evans, I was ready to move on. I figured if I’d have to sit on the bench, I might as well do it in a place I enjoyed. I’m happy to be back (in Houston).”

Cabell had a season similar to his 1983 campaign in 1984, batting .310 with 135 hits in 127 games. But with young Glenn Davis emerging at first base, Cabell became expendable. On July 10, 1985, the Astros sent Cabell to the Dodgers for Rafael Montalvo and Gérman Rivera.

The Dodgers were in the midst of a push for the NL West title, but the rest of the summer would present Cabell with the most challenging days of his career.

Cabell immediately stepped into the Dodgers’ lineup at third base and stayed there through the next month-and-a-half. But on Aug. 31, Los Angeles acquired four-time NL batting champion Bill Madlock from the Pirates and installed him at third. Meanwhile, Cabell’s name became front-page news across the country.

Cabell testified in a federal court on Sept. 8, 1985, that he had used cocaine. In a trial focusing on Curtis Strong, who was accused of supplying drugs to baseball players, Cabell said recreational drug use was rampant throughout the game.

“I used (cocaine) more in 1981, the strike year,” Cabell testified. “We weren’t playing and I didn’t have anything else to do.”

Cabell spent much of the rest of the season at first base, finishing the year with a .272 batting average in 117 total games. He started two games at first base in the NLCS vs. the Cardinals and appeared in five overall, hitting .077 (1-for-13) as St. Louis won the NL pennant in six games.

On Feb. 28, 1986, MLB Commissioner Peter Ueberroth suspended Cabell and six other players for one season. Ueberroth also said the suspensions would be lifted if each player donated 10 percent of their salary to drug prevention programs, agreed to random drug testing for the rest of their careers and agreed to perform 100 hours of community service over the next two years.

Cabell quickly agreed to the conditions.

“I’ve always wanted to get it over with,” Cabell told the AP. “I’m going to agree with what (the Commissioner) says to do. Then it’s over with. I thank the Dodgers for standing by me.

“It’s been a long time. I figured something had to happen sooner or later. I’ve been waiting for this to end for a long time.”

Cabell played in 107 games in 1986, batting .256 off the bench. With his contract expiring, Cabell filed for free agency but found no offers. But he continued to fulfill the conditions of his punishment, speaking to groups throughout 1987 about the perils of drug abuse.

Armand Markarian, a spokesman for St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica, Calif., told The New York Times in 1987 about Cabell’s talk with athletes at Santa Monica College.

“They had some pretty challenging questions, like ‘How could you do that to your body?’” Markarian said. “He said it happened at a weak moment, that he thought it would help his game. He won them over and got a standing ovation.”

Cabell’s playing career was over but his connection to the game continued. He joined the Astros’ broadcast crew on Home Sports Entertainment in 1991 and hosted Astros Report on KCOH radio from 1991-96. Cabell was a member of the Board of Regents at Texas Southern University from 1995-2001 and served as the school’s interim athletic director in 2000.

On Nov. 17, 2004, Cabell was named as Special Assistant to Astros general manager Tim Purpura after serving as a team consultant for the previous four months. His role with the team’s front office has continued for more than 20 years.

Over 15 big league seasons, Cabell hit .277 with 1,647 hits, 263 doubles and 238 stolen bases. After climbing to the big leagues as an undrafted free agent, Cabell became one of the most respected players in the game.

“Enos Cabell knows how to play the game,” Tigers manager Sparky Anderson told the Detroit Free Press in the spring of 1983. “If every guy on this club had the knowledge of baseball Enos Cabell has…I’d go to sleep easy every night. He’s identical to what Joe Morgan was for me in Cincinnati. He knows everything about playing this game.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum