- Home

- Our Stories

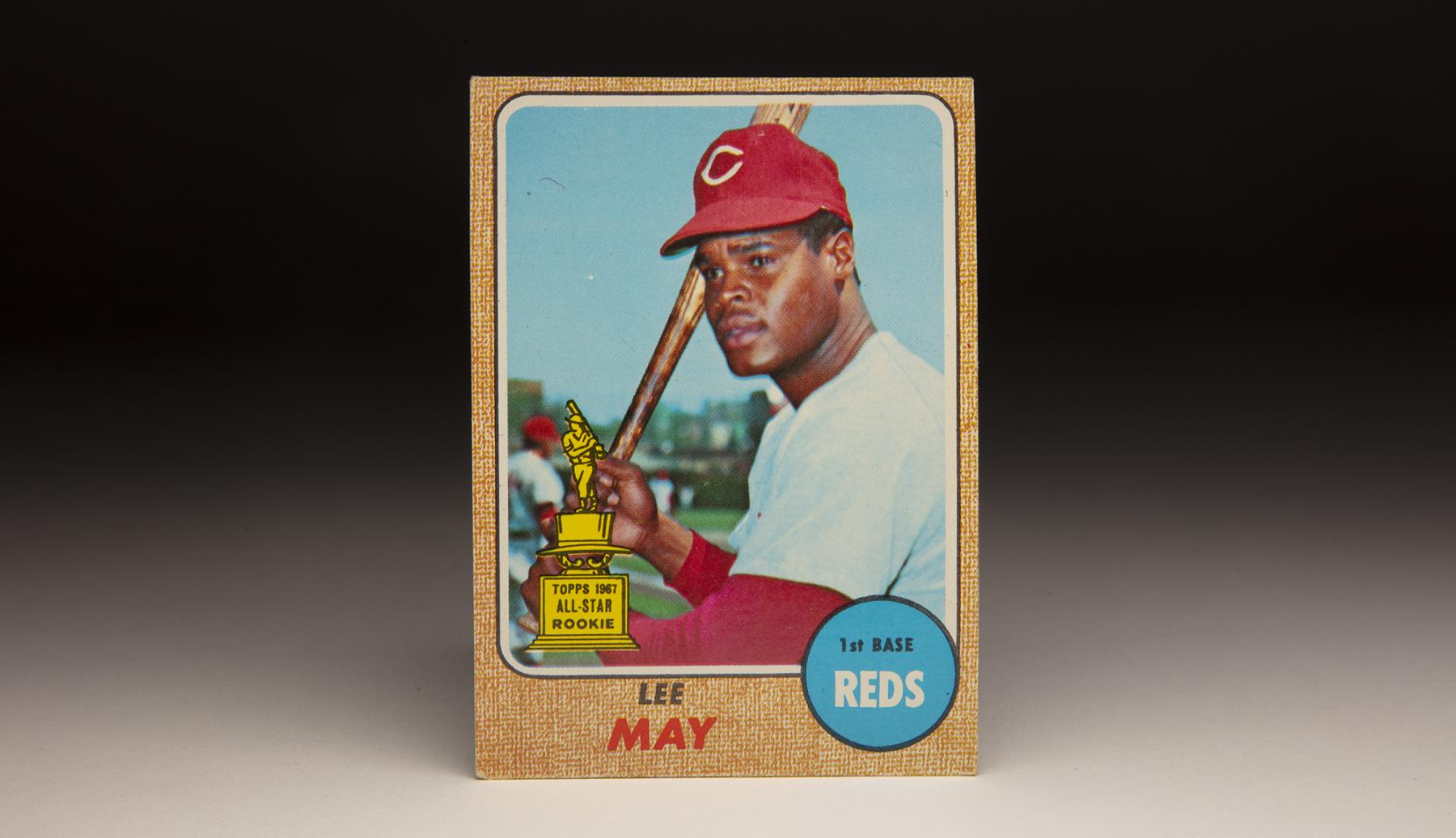

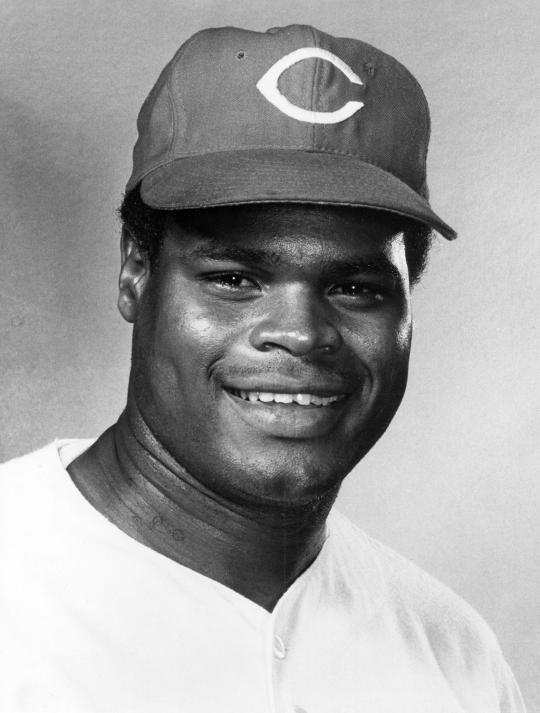

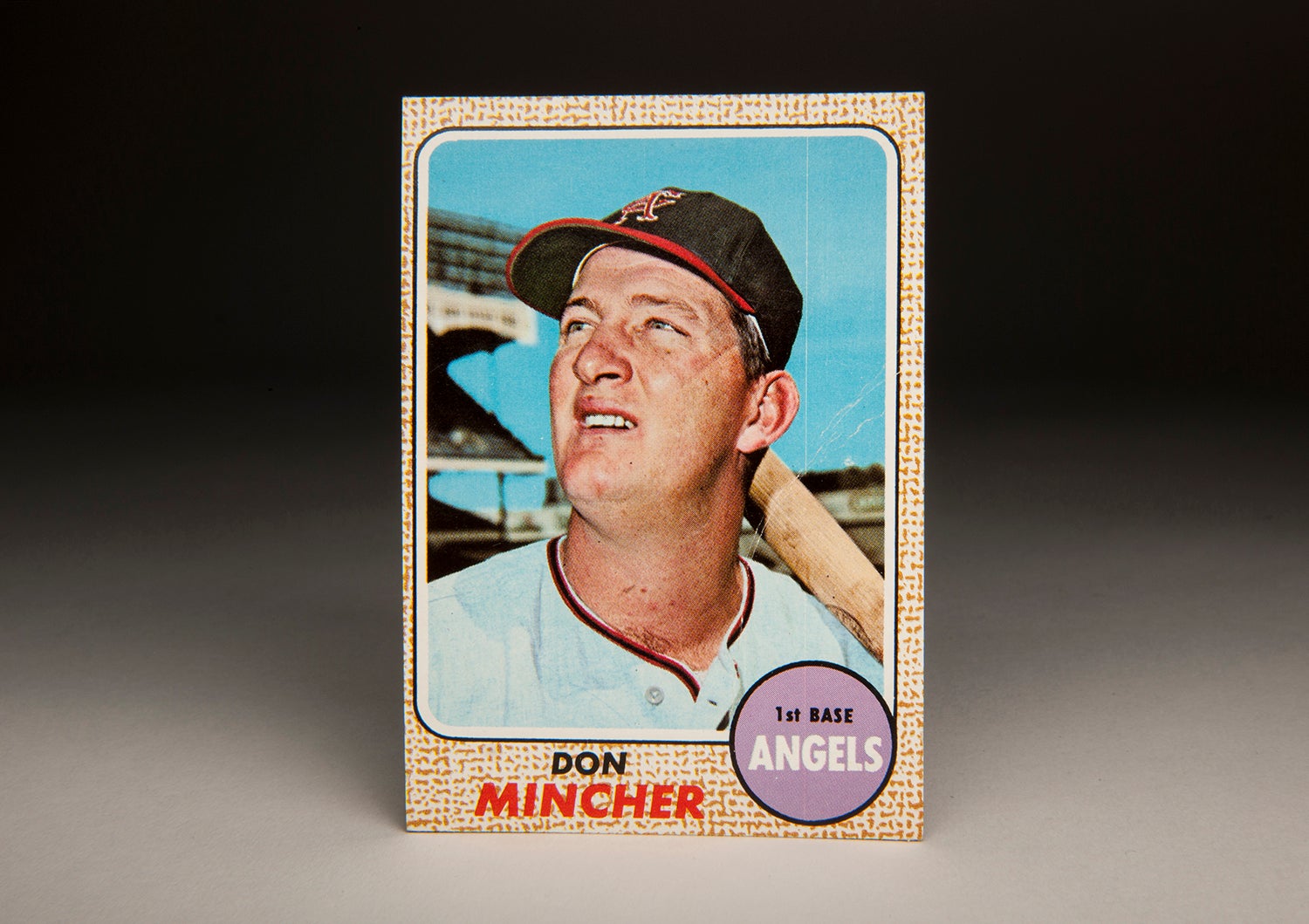

- #CardCorner: 1968 Topps Lee May

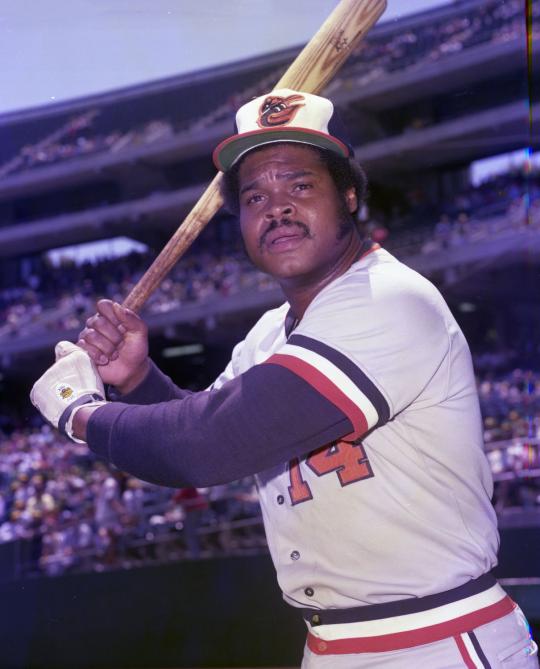

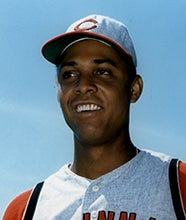

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Lee May

The video is on an endless loop of World Series highlights, one that will be played as long as the Fall Classic enthralls fans.

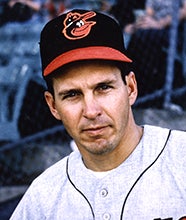

Hall of Famer Brooks Robinson ranges far into foul territory in Game 1 in 1970, stabbing a ball that had bounced over the third base bag. With one incredible motion, Robinson straightens up and fires the ball to first base, where Orioles teammate Boog Powell catches it on a short hop off the Riverfront Stadium turf.

Umpire Red Flaherty delivers an uppercut to the air with his right fist, signaling the runner out and starting the World Series Most Valuable Player journey for Robinson.

The batter who was out at first base was Lee May, who already recorded a single and a two-run homer that day for the Cincinnati Reds. And if it hadn’t been for Robinson’s heroics, May might have been remembered as the best player in that World Series.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

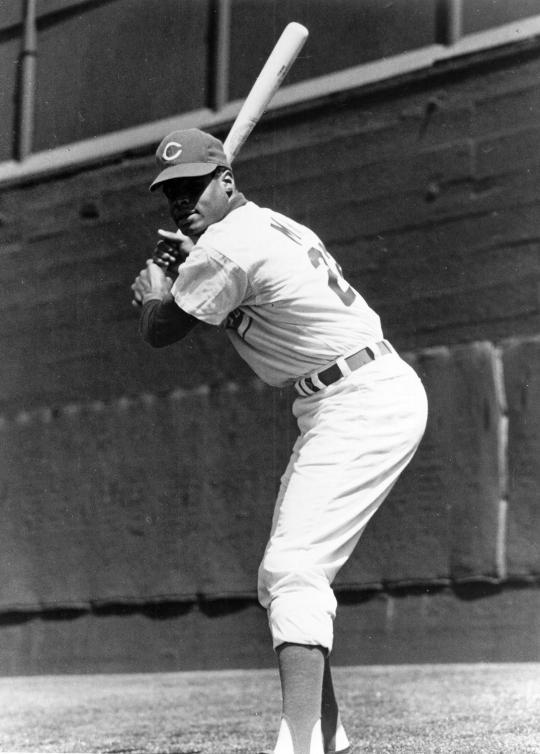

Born March 23, 1943, in Birmingham, Ala., Lee Andrew May excelled in youth sports and was often the biggest boy in his class. His brother, future major leaguer Carlos May, was born five years after Lee.

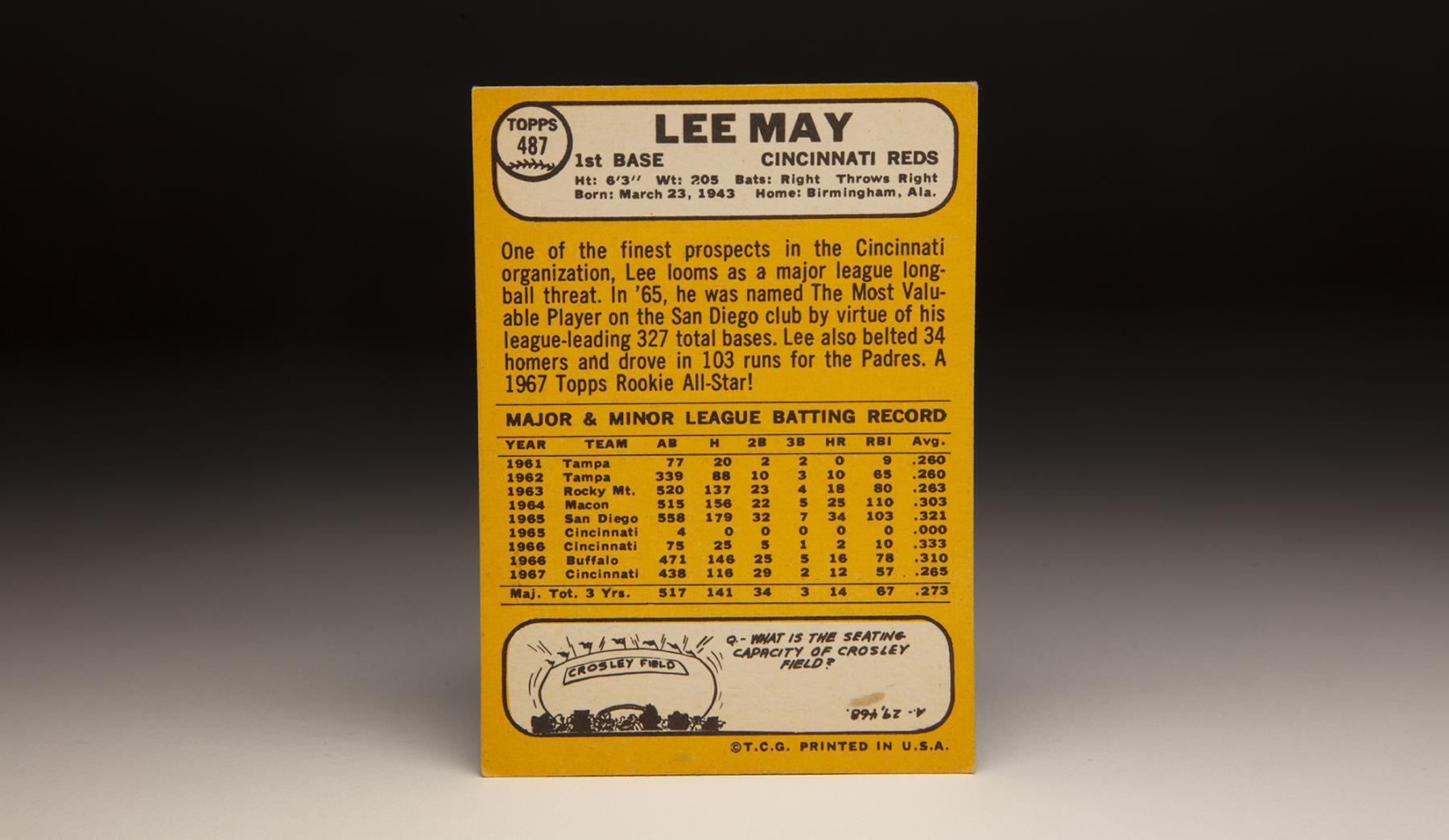

After graduating high school, Lee – who had grown into a muscular 6-foot-3 frame, received college football scholarship offers but opted to sign as an amateur free agent with the Reds on June 1, 1961. He spent his first two pro seasons with the Tampa Tarpons of the Class D Florida State League, then was promoted to Class A Rocky Mount of the Carolina League in 1963, where he hit 18 home runs and drove in 80 runs after a slow start that saw him hitting .222 with two home runs as late at June 1.

Then in 1964, the 21-year-old May put himself firmly on the Reds’ radar by hitting .303 with 25 homers and 110 RBI for Double-A Macon of the Southern League. The next season with Triple-A San Diego, May was named the Pacific Coast League’s MVP after hitting .321 with 34 homers and 103 RBI.

He debuted for the Reds on Sept. 1, 1965, and appeared in five games that month as a pinch hitter or pinch runner. He made the Reds’ Opening Day roster in 1966, but appeared in just six games as a pinch hitter before being sent back to Triple-A with the Buffalo Bisons. There, May hit .310 with 16 homers and 78 RBI and returned to Cincinnati in September, where he was installed as the Reds’ first baseman.

He recorded his first big league hit on Sept. 11 and stayed hot all month, finishing with a .333 average, 10 RBI and 14 runs scored in 25 games in relief of injured starter Deron Johnson. May ended the year on a 12-game hitting streak.

Johnson began the 1967 season as the Reds’ regular third baseman, making room for Tony Pérez at first base. But when Johnson injured a hamstring in early May, the Reds moved Pérez to third base and inserted May – who had impressed manager Dave Bristol in Spring Training – into the starting lineup. After a slow start, May finished the season with a .265 average, 12 homers and 57 RBI to earn the Sporting News National League Rookie of the Year Award.

Then in 1968, May took over full time at first base, hitting 22 home runs and driving in 80 runs with a .290 batting average – which ranked in the Top 15 in the NL – during the Year of the Pitcher.

“He should never be an easy out,” Bristol told the Cincinnati Enquirer. “He hits the ball too hard.”

In 1969, May was even better – totaling 38 homers with 110 RBI while earning his first All-Star Game selection. The Reds finished 89-73, but Bristol was replaced with Sparky Anderson following the season.

It would mark the start of the Big Red Machine era – and May would play a part both on and off the field.

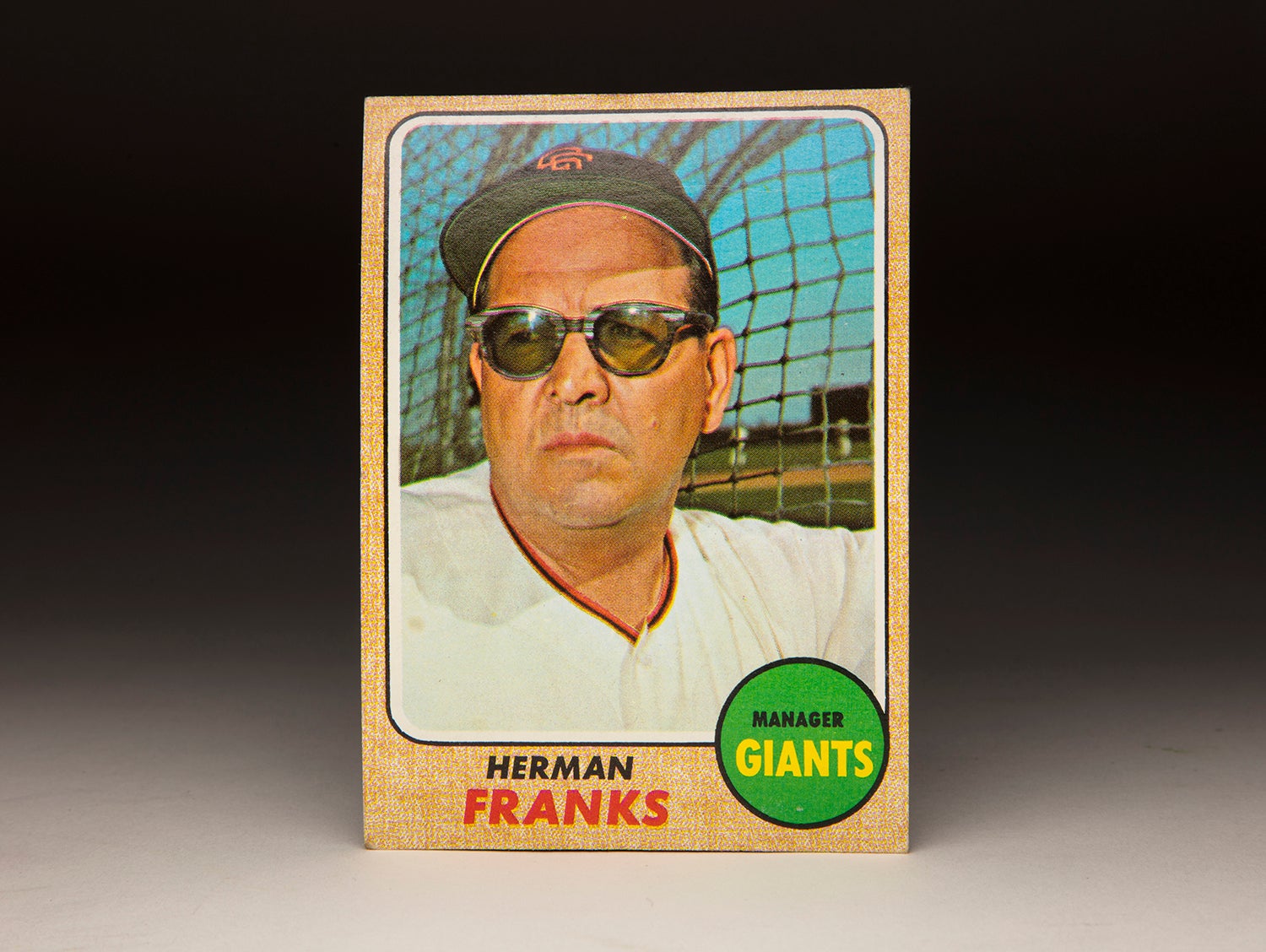

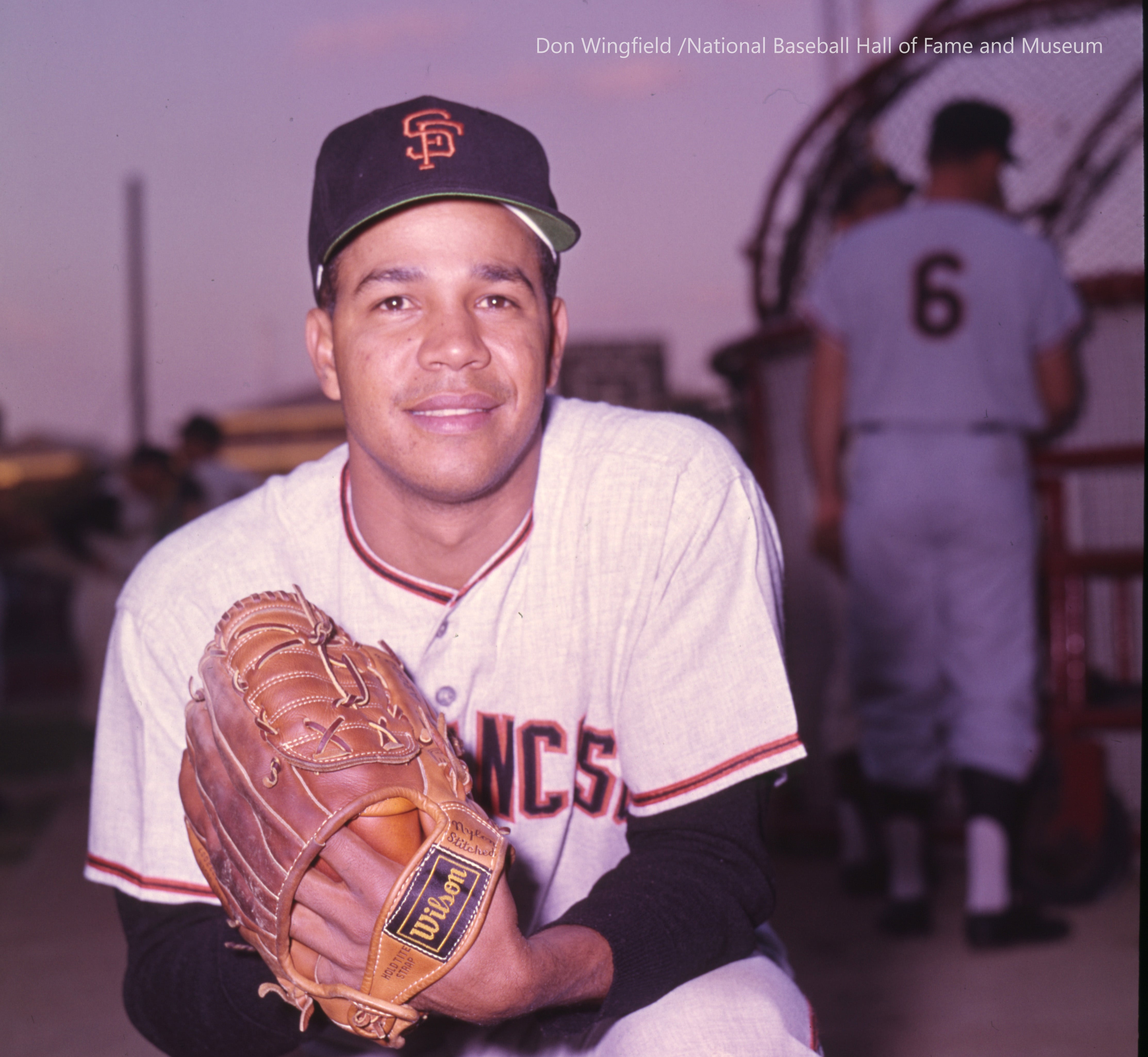

On June 24, 1970, May’s eighth-inning homer off future Hall of Famer Juan Marichal gave the Reds a 5-4 win over the Giants in the last game played at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field – and May caught the last out of that game following a ground ball to pitcher Wayne Granger. Six days later, the Reds moved into Riverfront Stadium.

“My gosh, I forgot what I was doing. No, I don’t have that ball,” May told the Dayton Daily News following the game. “I flipped it to a little kid who sits near our dugout.”

May, however, would always remember Crosley Field for one reason: “Short fences,” he told the Daily News.

But May’s power was so prodigious that it didn’t matter where he played. In the games prior to the Reds moving the Riverfront Stadium in 1970, May had 19 homers and 42 RBI. After the move, he had 15 homers and 52 RBI – finishing the season with 34 homers and 94 runs batted in as the Reds won 102 games and the NL West title.

After sweeping the Pirates in the NLCS, the Reds faced Robinson and the Orioles in the World Series. May hit .389 with two homers and eight RBI in the Orioles’ five-game victory, leading the team in hits, runs, homers and RBI.

“It was,” May told the Evening Sun, “a glorious time.”

His three-run home run in the top of the eighth of Game 4 turned a 5-3 Baltimore lead into a 6-5 Reds win in Cincinnati’s only victory of the Fall Classic.

“You think he didn’t kiss that ball?” Anderson asked rhetorically in the Cincinnati Enquirer. “You knew that was gone.”

In 1971, May hit 39 homers – matching his third-place finish in the NL from 1969 – and drove in 98 runs to earn the Reds team Most Valuable Player Award. But Cincinnati finished a disappointing 79-83, and general manager Bob Howsam decided a major overhaul was in order.

On Nov. 29, 1971, Howsam rocked the Winter Meetings by sending May, Tommy Helms and Jimmy Stewart to the Astros in exchange for Ed Armbrister, Jack Billingham, César Gerónimo, Denis Menke and Joe Morgan. The trade would pay dividends for the Reds for years, as Gerónimo and Morgan – who was on his way to the Hall of Fame – improved Cincinnati’s defense and Billingham stabilized the rotation.

It also made way for Pérez to return to his natural position of first base, where he would become one of the best clutch hitters of his generation.

“We feel we have enough power to win,” Howsam told the Enquirer. “May had his greatest year last year and we still finished fourth.”

For his part, May seemed unsurprised with the trade. For several weeks, his named had swirled in rumors – especially after Howsam asked May to stop playing basketball in the offseason.

Reds outfielder Bobby Tolan suffered a serious Achilles tendon injury while playing basketball prior to the 1971 campaign, costing him the entire year.

“I’m pretty sure it was,” May told the Dayton Daily News about basketball as being a factor in the trade. “I think they wanted to get rid of me last year, even though they denied it. But I still hate to go. My wife and kids fell in love with Cincinnati. We put down roots here. But that’s the way things go.”

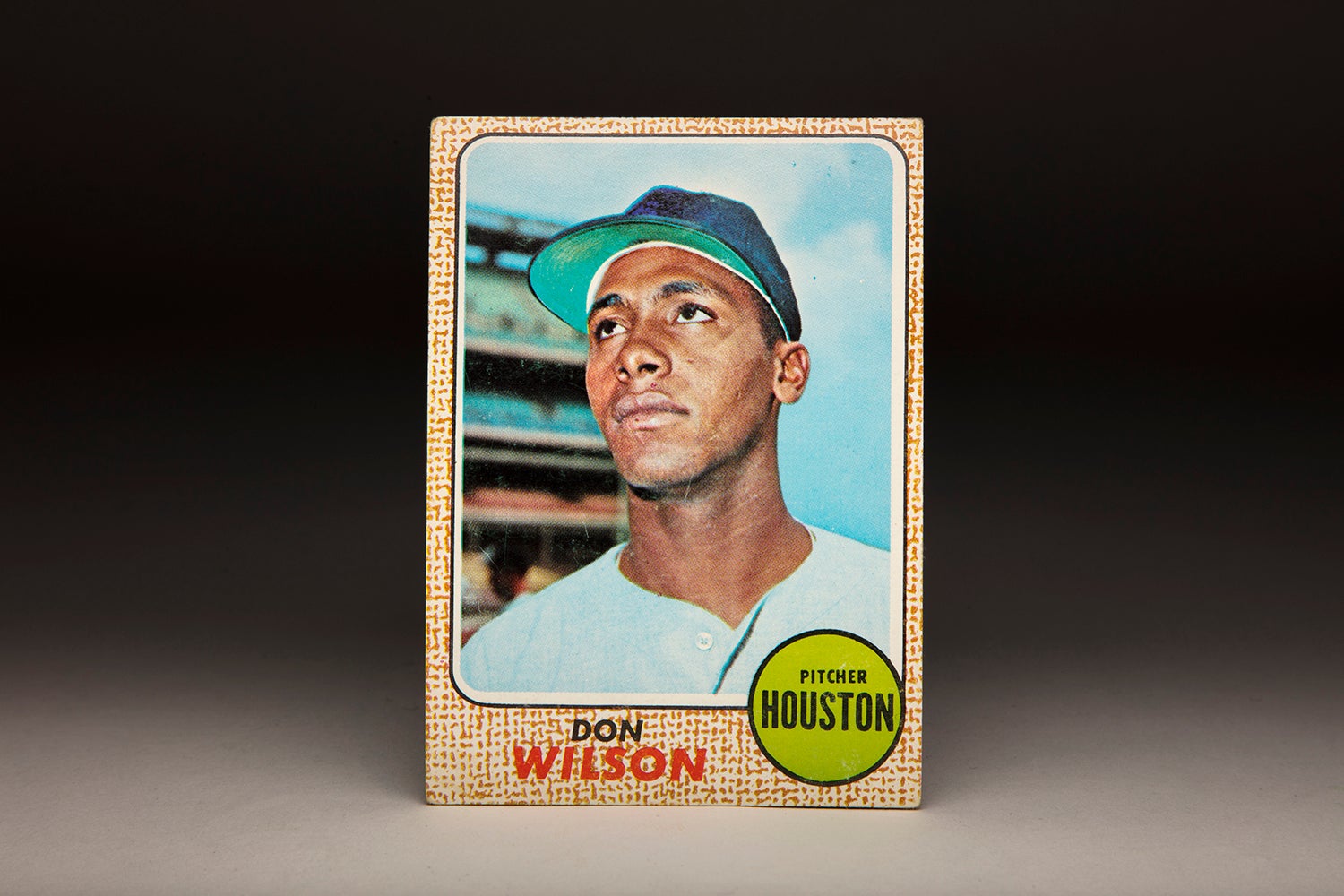

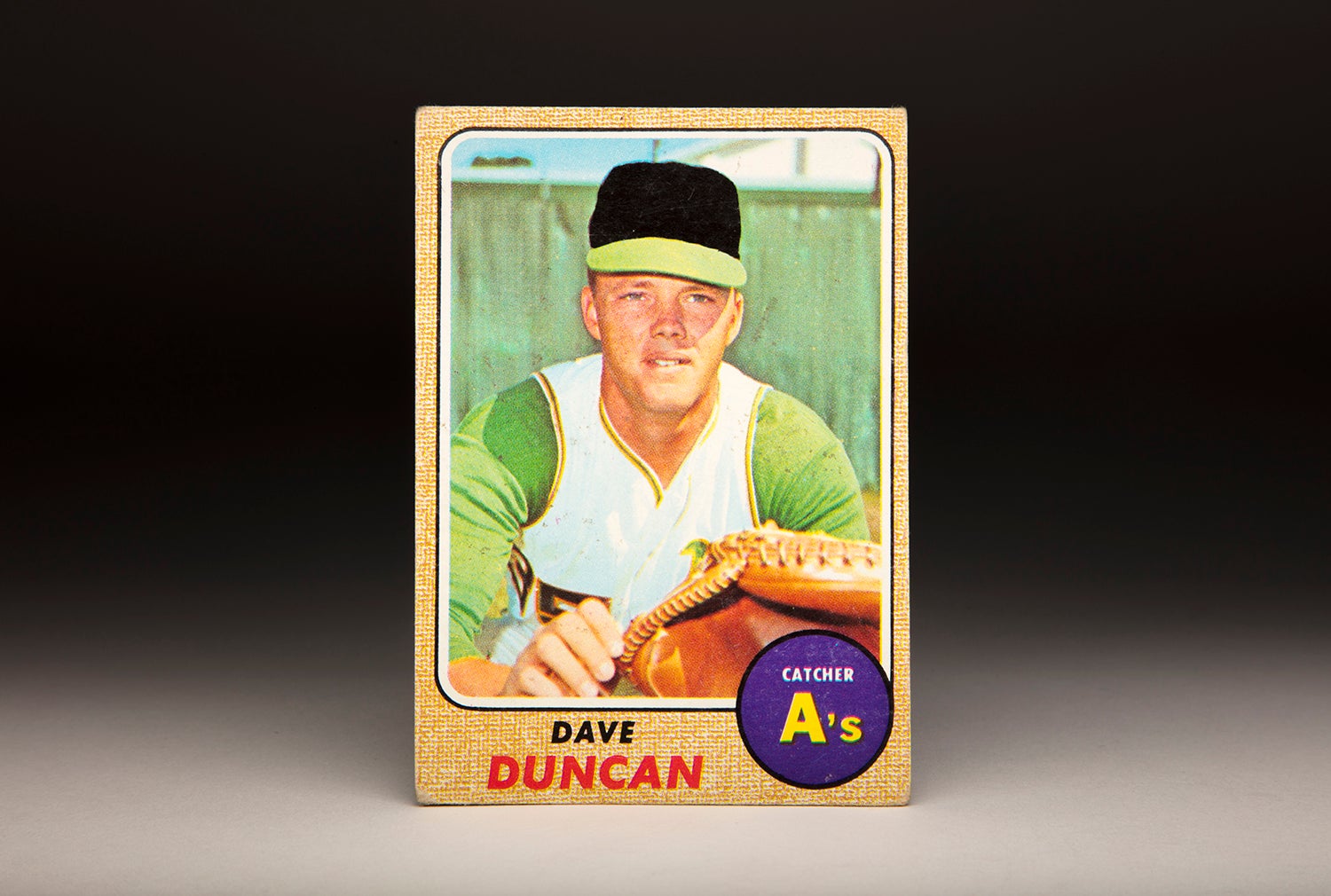

For their part, the Astros were thrilled to welcome May’s bat to their lineup. May led Houston with 29 home runs and 98 RBI in 1972 – pushing an Astros team featuring young stars like César Cedeño, Bob Watson and Jim Wynn to 84 wins.

May had another strong season in 1973, hitting 28 home runs and driving in 105 runs, but Houston finished 82-80. The next year, May provided his customary 24 homers and 85 RBI while the Astros finished 81-81.

Looking to get younger, Houston traded May and Jay Schlueter to the Orioles on Dec. 3, 1974, receiving prospects Rob Andrews and Enos Cabell in return.

In three seasons playing in the cavernous Astrodome, May averaged 27 homers and 96 RBI.

Orioles general manager Frank Cashen summed up the trade in two words. “More hitters,” Cashen told the Evening Sun.

May was thrilled with the trade, which sent him to a team that had won five of the last six American League East titles.

“I’m glad to be joining a contender,” May told the Evening Sun. “I’d rather leave (Houston) than be kept when I’m really not wanted.”

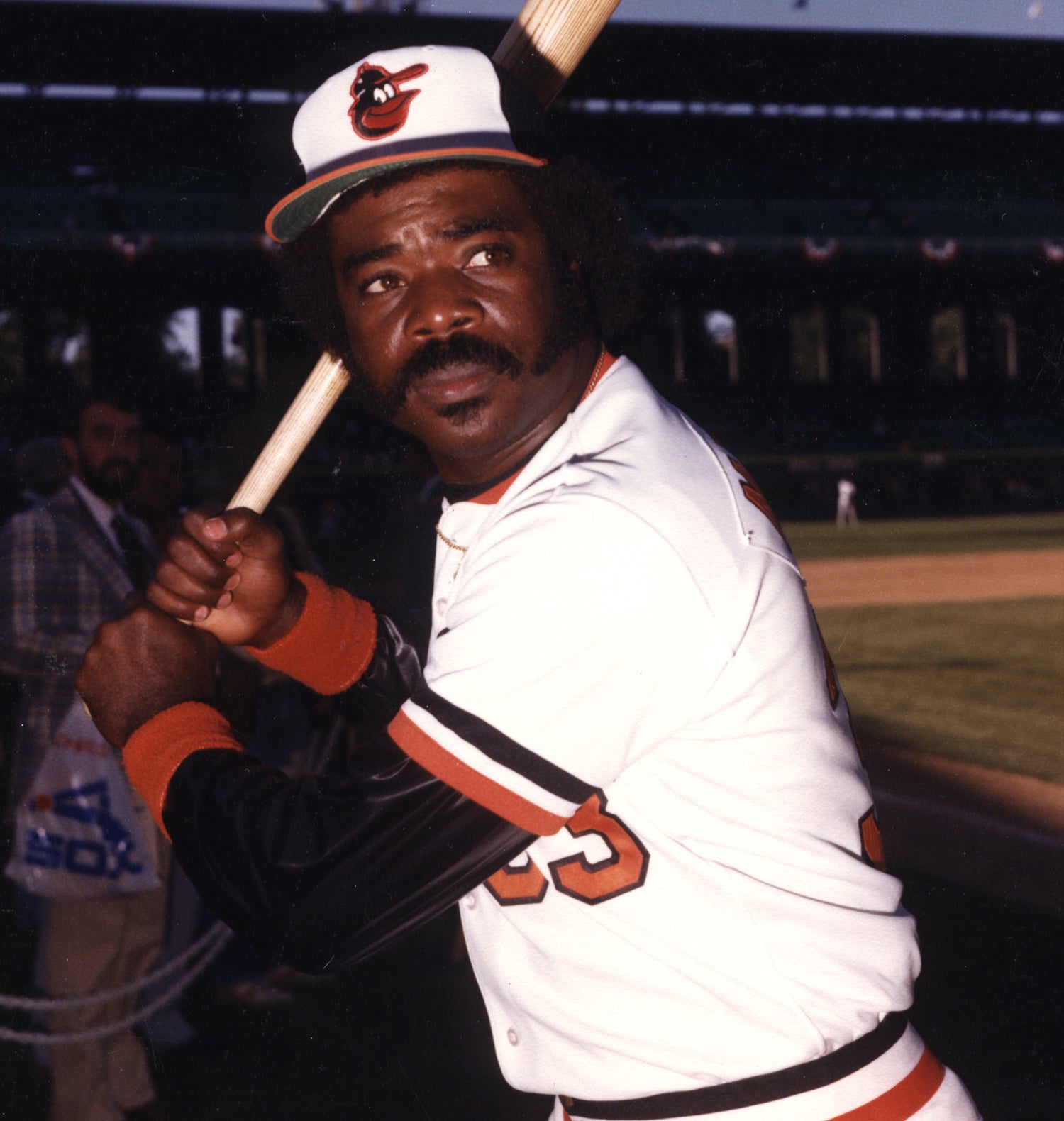

The Orioles installed May at first base and he hit 20 homers and totaled 99 RBI, but Baltimore slipped to second place in the AL East. In 1976, May hit 25 home runs and posted an AL-best 109 RBI, but once again Baltimore finished second.

Then in 1977, the Orioles debuted future Hall of Famer Eddie Murray, who won the AL Rookie of the Year Award with 27 homers and 88 RBI. Murray, a first baseman, played 111 games at DH while May – serving as the regular first baseman – hit 27 home runs and drove in 99 runs. But with May already 34 years of age and Murray only 21, the future was clearly in favor of Murray.

But even once he transitioned into a DH role, May continued to take grounders at first base in pregame nearly every day.

“Nobody ever had to tell him to do anything,” Orioles manager Earl Weaver told the Evening Sun, “and there’s nothing better for a manager than to have a veteran like that.”

In 1978, May appeared in 148 games – 140 as a DH. He finished with 25 homers and 80 RBI. The next season, the Orioles returned to the top of the division for the first time in five years and rolled into the World Series. But at that time, the use of the DH alternated years in the Fall Classic – and 1979 was a “National League” year. That meant May, who had 19 homers and 69 RBI as Baltimore’s primary DH – was relegated to two at-bats in the World Series.

“Lee May,” Weaver told the Associated Press prior to the World Series, “was a big part of our offense. What effect it has will depend on the other eight guys in the lineup.”

Baltimore lost to Pittsburgh in seven games.

Injuries began to take their toll on the 37-year-old May in 1980, and he appeared in just 78 games with seven homers and 31 RBI. It was his first season since 1967 where he did not total at least 19 home runs.

Only Reggie Jackson equaled May’s total of 12 seasons with at least 19 home runs from 1968-79.

When May’s contract expired after the 1980 season, he left Baltimore as a free agent.

“I have no regrets – especially about my time in Baltimore,” May told the Evening Sun. “I have only good thoughts about the time I spent here.”

May quickly signed a free agent deal with the Royals and spent the next two seasons with Kansas City as a bench player, retiring following the 1982 season after the Royals released him.

May finished his 18-year career with 354 home runs, 1,244 RBI and 2,031 hits. Only Willie Stargell, Reggie Jackson, Johnny Bench and Bobby Bonds had more home runs in the 1970s than May’s 270, and only Bench and Pérez had more RBI’s than May’s 936.

May coached for several teams from the 1980s into the 2000s, serving as the hitting coach on the Royals’ 1985 World Series champions.

He passed away on July 29, 2017.

“He is what you would call a true professional,” Weaver told the Evening Sun. “He has done everything he has ever been asked to do for this club.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum