- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1968 Topps Dave Duncan

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Dave Duncan

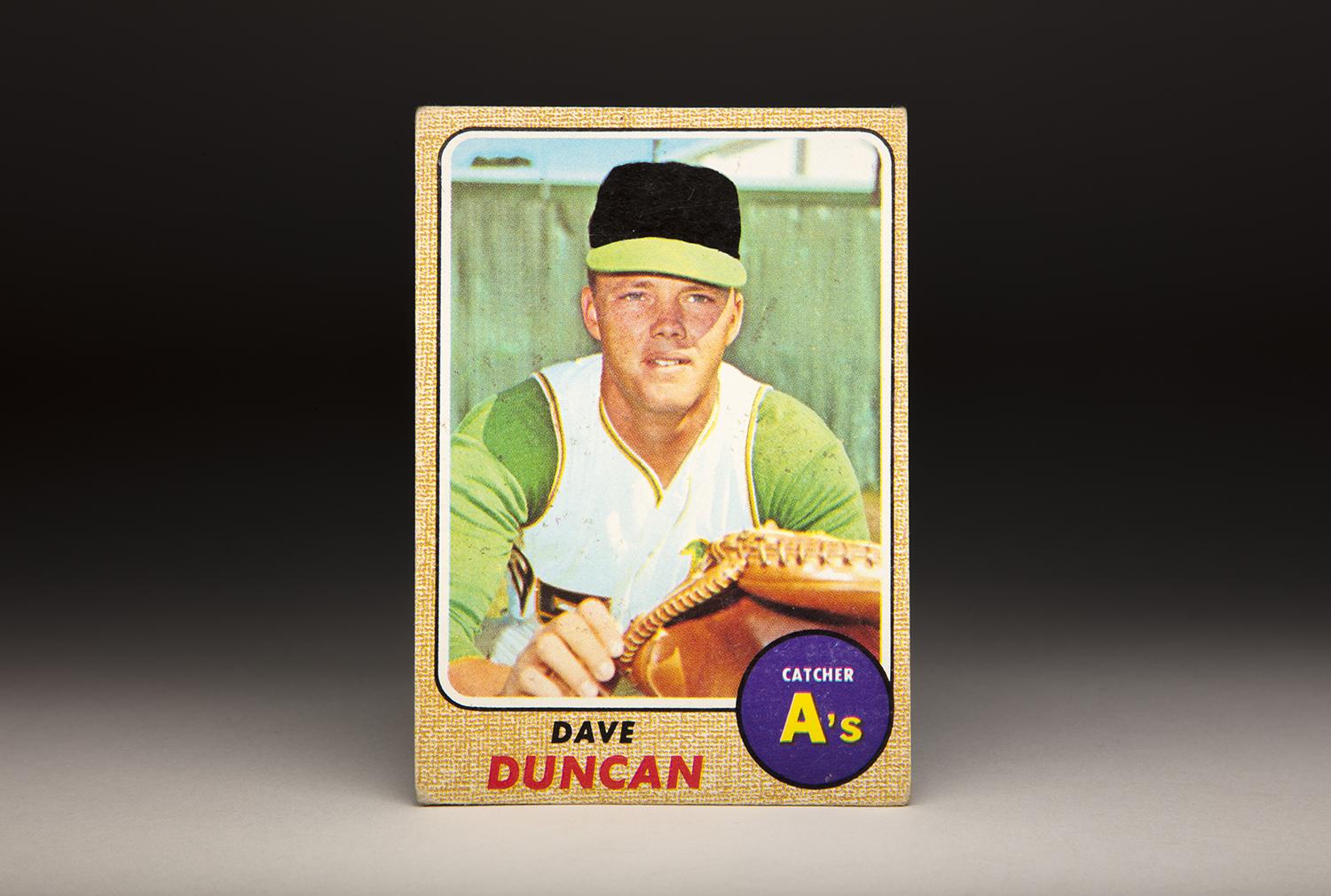

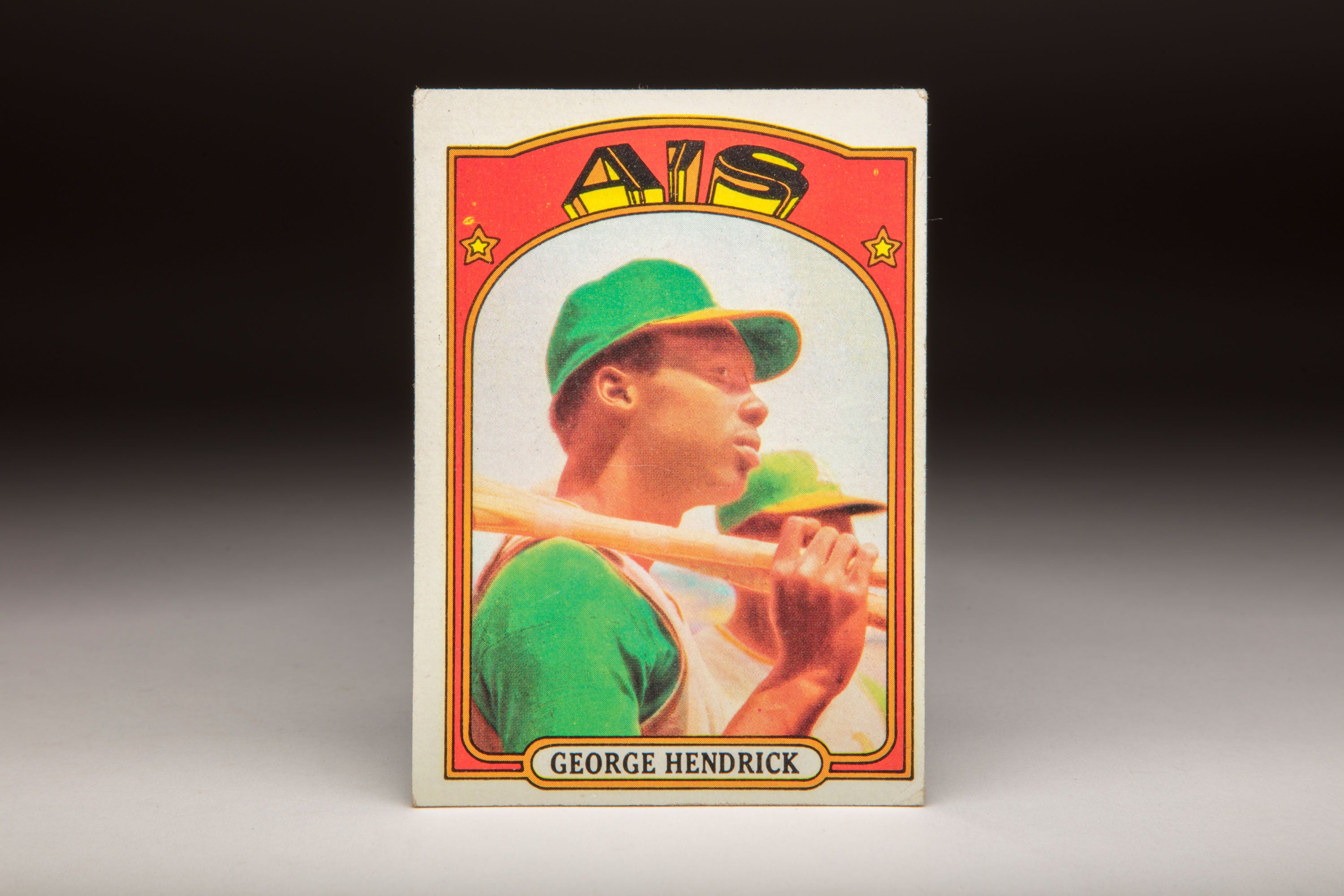

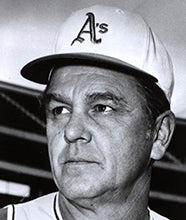

For the longest time, I couldn’t figure out why Topps decided to black out the crown of Dave Duncan’s cap on his 1968 card. After all, Duncan had played for the A’s during the 1967 season, so why the need to airbrush over the top half of the cap, thereby preventing us from seeing the logo on the hat?

As it turned out, I wasn’t very bright. When I pointed out the oddity of the Duncan card (and other members of the ’68 A’s) to another card collector, he matter-of-factly explained the reason for the blackening of the cap. In 1968, the A’s began playing their games in Oakland. In 1967, they had played in Kansas City. Given the franchise shift, and considering that the old Kansas City cap featured the letters “KC” on the crown of the cap, Topps simply wanted to eliminate any reference to Kansas City. With no new photographs available to show the new Oakland cap, Topps decided the easiest path was simply to black out the crown of the cap.

That makes perfect sense and should have been obvious to me from the beginning, but another question does remain. Why didn’t Topps use green to color the crown of the cap, rather than the black, which creates an odd two-tone effect of black and green? Perhaps Topps found it difficult to find the right shade of green to match the bill of the cap, but that’s simply a guess on my part. I honestly don’t know. Perhaps another card collector can help me out with that mystery, too. But that’s a story for another day.

Duncan’s card is also noteworthy for another reason. He is seen wearing the A’s’ distinctive uniforms of the late 1960s, notable for their bright green color and the sleeveless vest jerseys. Like the Pittsburgh Pirates of that era, the Pirates preferred the vest look, which gave them an unusual appearance in contrast to the other 18 teams in the major leagues.

Duncan’s appearance on his 1968 card was his second for Topps. He had actually appeared on his first card four years earlier, when he was featured as one of the Kansas City A’s top prospects for the 1964 season. (He shared the rookie card with fellow minor leaguer Tommie Reynolds.) The four-year gap in card appearances, while certainly not unprecedented, reflected Duncan’s unusual career arc.

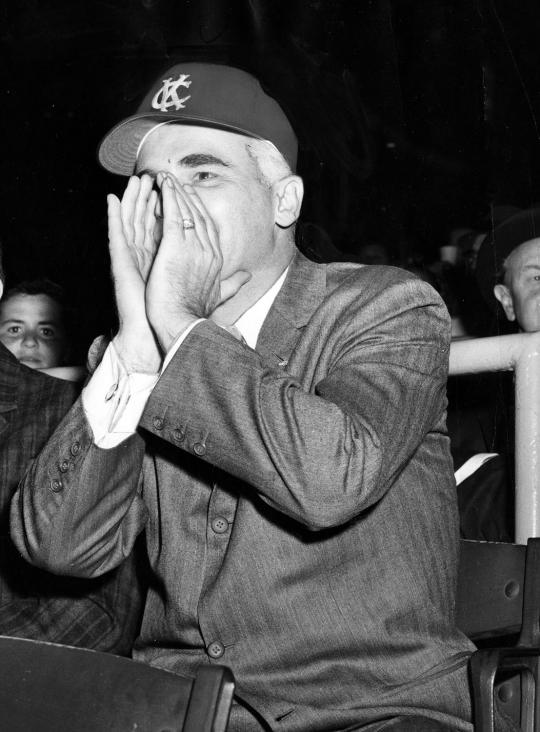

There was good reason for Topps to include Duncan in its 1964 set. As a bonus baby who had received a huge sum of money from Kansas City owner Charlie Finley upon signing his first contract, the rules stipulated that Duncan had to spend at least one full season on the major league roster. So the A’s kept him around for the entire ‘64 season, even though he was only 18 and clearly not ready for major league duty. Spending most of his rookie season on the bench, Duncan hit only .170 in limited work and then headed back to the minor leagues for the 1965 season.

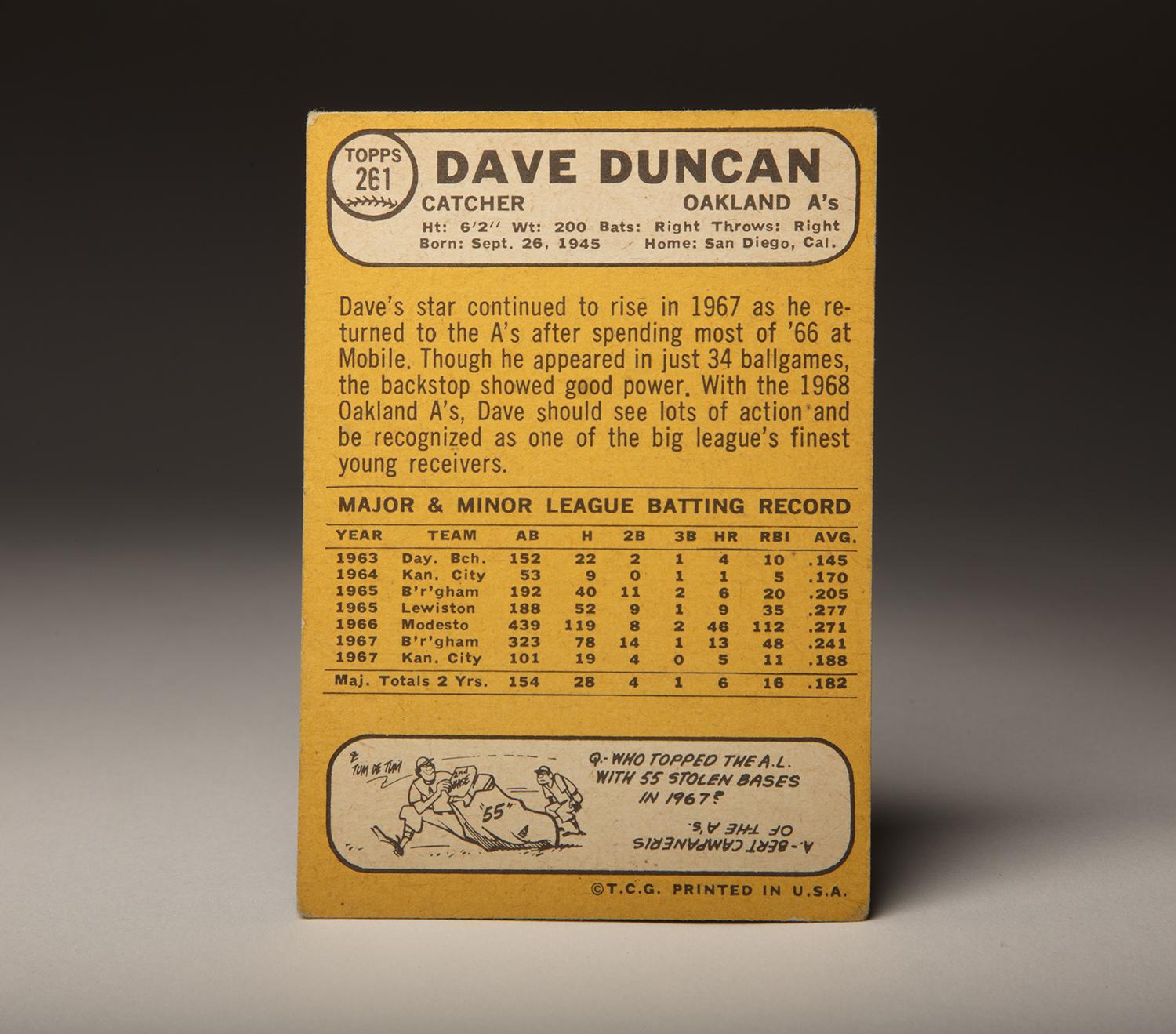

When Dave Duncan's photograph for his 1968 Topps card was taken, the Athletics were still playing in Kansas City. After the franchise switch to Oakland, his cap was blackened out to remove all traces of the former location. (Milo Stewart Jr. / National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

For the next two and a half seasons, Duncan remained in the Kansas City farm system, where he made a steady climb. In 1967, he played for the famed Southern League team, the Birmingham A’s, who featured 19 future major leaguers, including Duncan, Joe Rudi, Reggie Jackson and Rollie Fingers. In June, the A’s summoned Duncan from Birmingham, marking the first of his two call-ups that summer. Duncan then returned to Birmingham, where he helped the minor league A’s wrap up the Southern League title, before coming back to Kansas City in September. By now, Topps believed that Duncan was worthy of an appearance in its next set of cards, coming out in the spring of 1968.

As it turned out, Duncan did not start 1968 in Oakland. Instead, the A’s optioned him to Triple-Vancouver, where he did his best to prove his muster by hitting .316 in 35 games. By June, the A’s felt that Duncan was ready for a fulltime recall. Manager Bob Kennedy made Duncan his No. 1 catcher. Duncan remained in that role for the rest of the season, despite hitting .191 with a .263 slugging percentage.

Duncan’s hitting actually worsened in 1969, as his OPS fell to an embarrassing .457. But he began to find himself in 1970, when he hit 10 home runs and earned additional playing time.

After the 1970 season, Duncan became involved in an unwanted controversy. Finley fired John McNamara as manager, but rather than provide a traditional reason for the firing, he offered up some rather twisted logic. At the press conference announcing McNamara’s termination, Finley ranted about Duncan, who was no more than the team’s second-string catcher. The Finley tirade came in response to something that Duncan had said a few days earlier. “There’s only one man who manages this club: Charlie Finley,” Duncan had informed Ron Bergman of The Sporting News. “And we’ll never win so long as he manages it. We had the team to win it… But because of the atmosphere he [Finley] creates, there’s no spirit, no feeling of harmony. We should be close like a family, but it’s not here.”

According to Finley, when he learned of Duncan’s remarks, he decided that it was time to fire McNamara. “[McNamara] didn’t lose his job,” Finley claimed in an interview with the Associated Press. “His players took it away from him.” Finley reasoned that a manager who could not prevent his players – like Duncan – from making critical remarks about their owner had lost control of his own clubhouse. By that reasoning, Finley felt justified in firing McNamara.

Few of the reporters attending the press conference bought Finley’s argument. They felt that Finley was simply trying to create an excuse to fire a manager whom he wanted to replace anyway. So Finley fired the laid-back McNamara and brought in the far more intense Dick Williams to manage the team.

The change would not only help the A’s over the next three seasons, but it would also help Duncan in the short term. Appearing in a career-high 103 games for Williams in 1971, Duncan played well enough to make the American League All-Star team. Although his hitting would fall off during the second half of the season, he still finished with 15 home runs, by far his best total to date, and gave Williams brilliant defensive play behind the plate.

In 1972, Duncan would earn even more playing time from Williams. This time appearing in 121 games, Duncan hit 19 home runs, giving the A’s power and defense at an important position. With Duncan now the No. 1 catcher, the A’s won their second straight American League West title.

In an offbeat way, Duncan came to embody the 1972 version of the A’s. That was the same team that grew mustaches and sported facial hair, responding to a challenge from Finley, who promised each player $300 if he grew a mustache by Father’s Day. Every one of the players did so, including Duncan. But Duncan took it a step further. He grew a beard that looked scraggly and unkempt, and also allowed his blonde hair to grow so long that that it covered the collar of his jersey. No other player on the A’s came close to matching the hair length of Duncan, who looked like he was ready to attend a Grateful Dead concert by midsummer.

In a sport known for a conservative culture, especially in the early 1970s, Duncan epitomized the look of a hippie. For some, the appearance was disconcerting, especially to those who did not know him. “With that long hair, he kind of looked goofy as a player,” Tigers shortstop Eddie Brinkman once told the Chicago Sun-Times. “But once you get to know him, you realize he’s one of the kindest, smartest men you’ll ever meet.” Brinkman would eventually work with Duncan as a coach on the staff of the Chicago White Sox, the two becoming close friends.

Duncan and the rest of the “Mustache Gang” A’s took the West by five games, setting the stage for a Championship Series showdown against the Detroit Tigers. Williams reduced Duncan’s playing time in the playoffs, opting to put his best hitting team on the field, with Gene Tenace behind the plate and Mike Epstein at first base. Now playing a role as the backup catcher, Duncan came to bat only three times, drawing a walk. Still, the A’s defeated the Tigers in five games, giving Duncan his first taste of World Series play.

At the start of the Series, Duncan again found himself on the bench, limited to pinch-hitting opportunities. But as the Series progressed, with the Reds running aggressively again Tenace, Duncan received the start in the decisive Game 7. At bat, he went 0-for-3, but behind the plate, he massaged a quartet of Oakland pitchers through a low-scoring, one-run game and threw out Joe Morgan attempting to steal, helping the A’s win their first championship in Oakland.

With a world championship in tow, Duncan hoped to cash in with a better contract in 1973. When he and Finley could not reach agreement on a new deal, Duncan decided to hold out at the start of Spring Training. On March 10, Finley automatically renewed Duncan’s contract. Three days later, Finley publicly informed both Duncan and fellow holdout, ace left-hander Vida Blue, that they were essentially replaceable. “We’re going to make every effort to repeat as World Champions,” Finley said in an interview with United Press International. “A Vida Blue or a Dave Duncan aren’t going to stand in my way. We certainly hope they play, but if they don’t, I assure you we’ll get along without them very well.”

When Duncan finally reported to camp, he agreed to work out with the team but declined to sign his renewed contract. The longtime catcher wanted a raise from $30,000 to $50,000. Finley wouldn’t budge from $40,000. Duncan hinted that he might not play for the A’s come Opening Day.

On March 24, Finley exacted his revenge. That day, Finley announced a trade, sending Duncan and outfielder George Hendrick to the Cleveland Indians for catcher Ray Fosse and utility infielder Jack Heidemann. On the surface, the deal allowed the A’s to rid themselves of two unhappy ballplayers and return Tenace to first base, where he was more comfortable defensively.

Duncan reacted to the trade with a sense of relief, as if he had been released from a prison. “I was very happy to be traded,” Duncan told the New York Times. “It eliminated a lot of the mental hassles I had.”

For the next two years, Duncan became the Indians’ primary catcher. He hit a combined 33 home runs over that span, while continuing to do his usual good work behind the plate, but his declining batting average and inability to reach base motivated the Indians to make a change. In the spring of 1975, the Indians included Duncan in a four-man deal, sending him and minor league outfielder Alvin McGrew to Baltimore for slugging first baseman Boog Powell and lefty reliever Don Hood.

With the Orioles, Duncan became a platoon player, switching on and off with the left-handed hitting Elrod Hendricks. After hitting 12 home runs for the O’s in 1975, his power production fell off considerably in 1976. That, combined with a batting average near .200, resulted in a trade in November. The Orioles sent Duncan to the Chicago White Sox for veteran outfielder Pat Kelly.

Although Duncan appeared on a 1977 Topps card with airbrushed White Sox colors (and his trademark long hair in full evidence), he would never appear in an actual game for Chicago. With the White Sox committed to playing two younger catchers, Brian Downing and Jim Essian, Duncan became expendable. On March 30, just days before the start of the new season, the White Sox released Duncan. That transaction ended his playing career at the age of 31.

For many players, the end of their playing days marks the end of their formal association with the game. For Duncan, that was not the case. In fact, he was just getting started. After dabbling in the baseball novelties industry for a year, Duncan returned to Organized Ball in 1978 by rejoining the Indians as their bullpen coach. Two years later, he would earn a promotion to pitching coach, even though his entire playing career had been spent as a catcher.

Dave Duncan was signed by Kansas City A’s owner Charlie Finley, pictured above, as a bonus baby in 1963. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

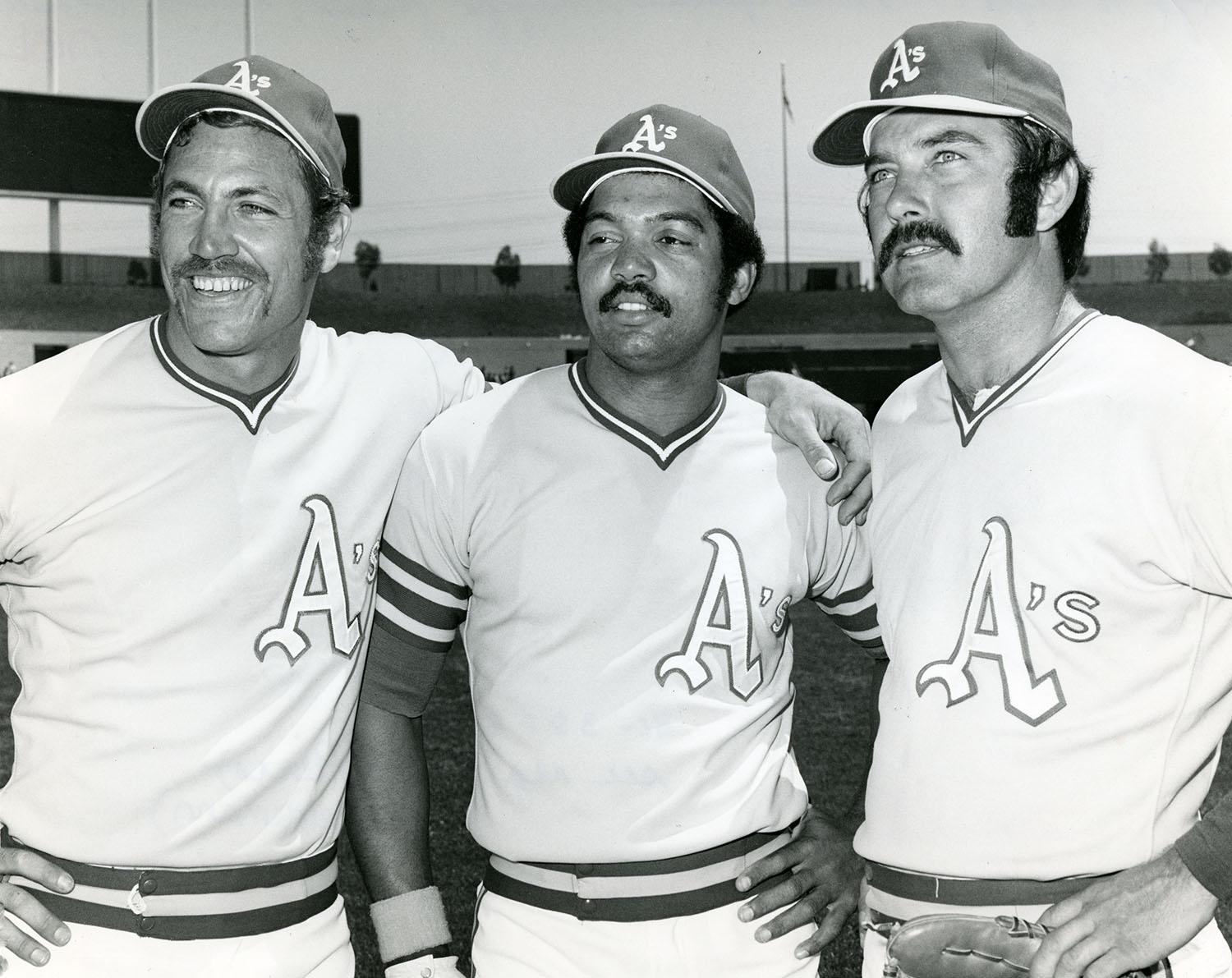

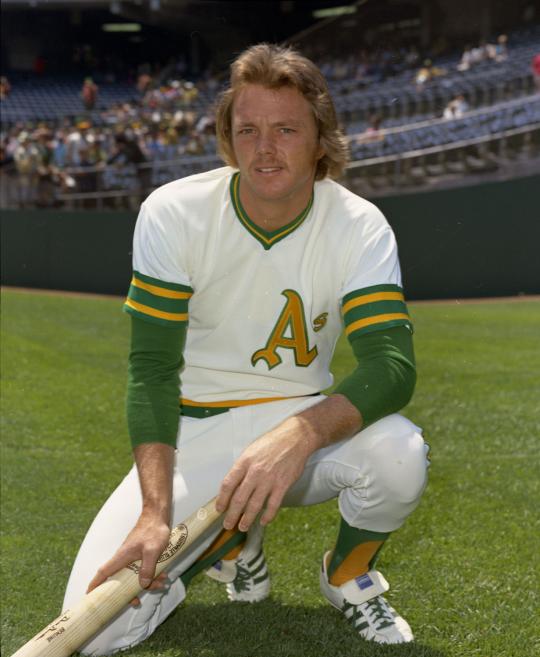

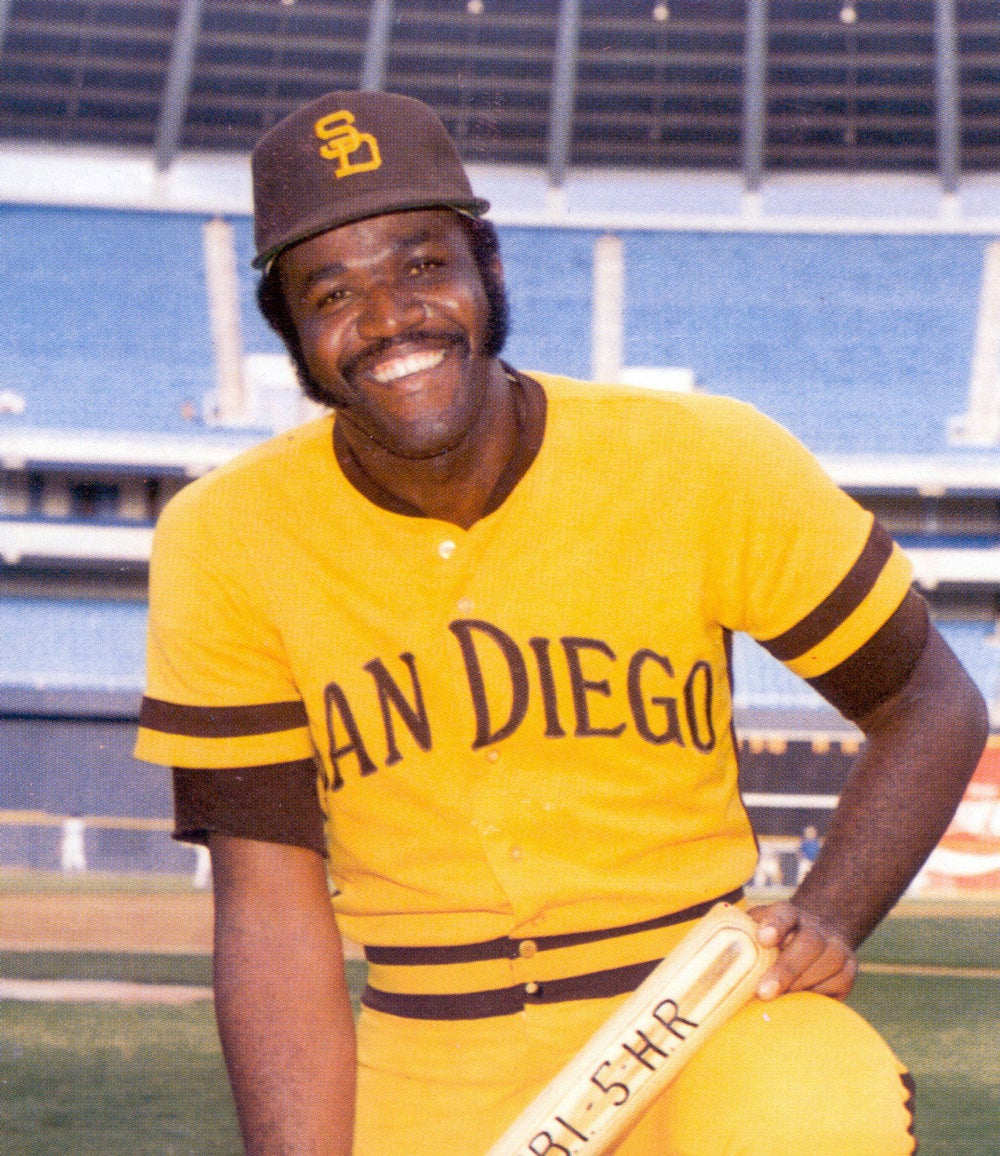

Dave Duncan, pictured above in 1972, played with the Athletics for seven seasons. (Doug McWilliams / National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

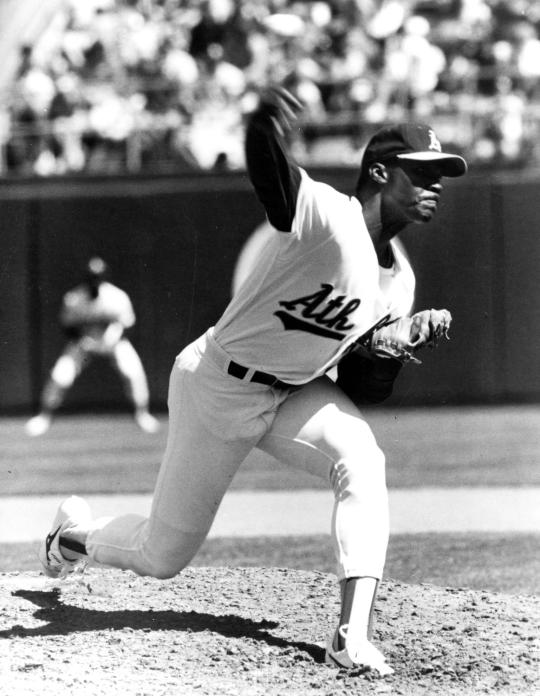

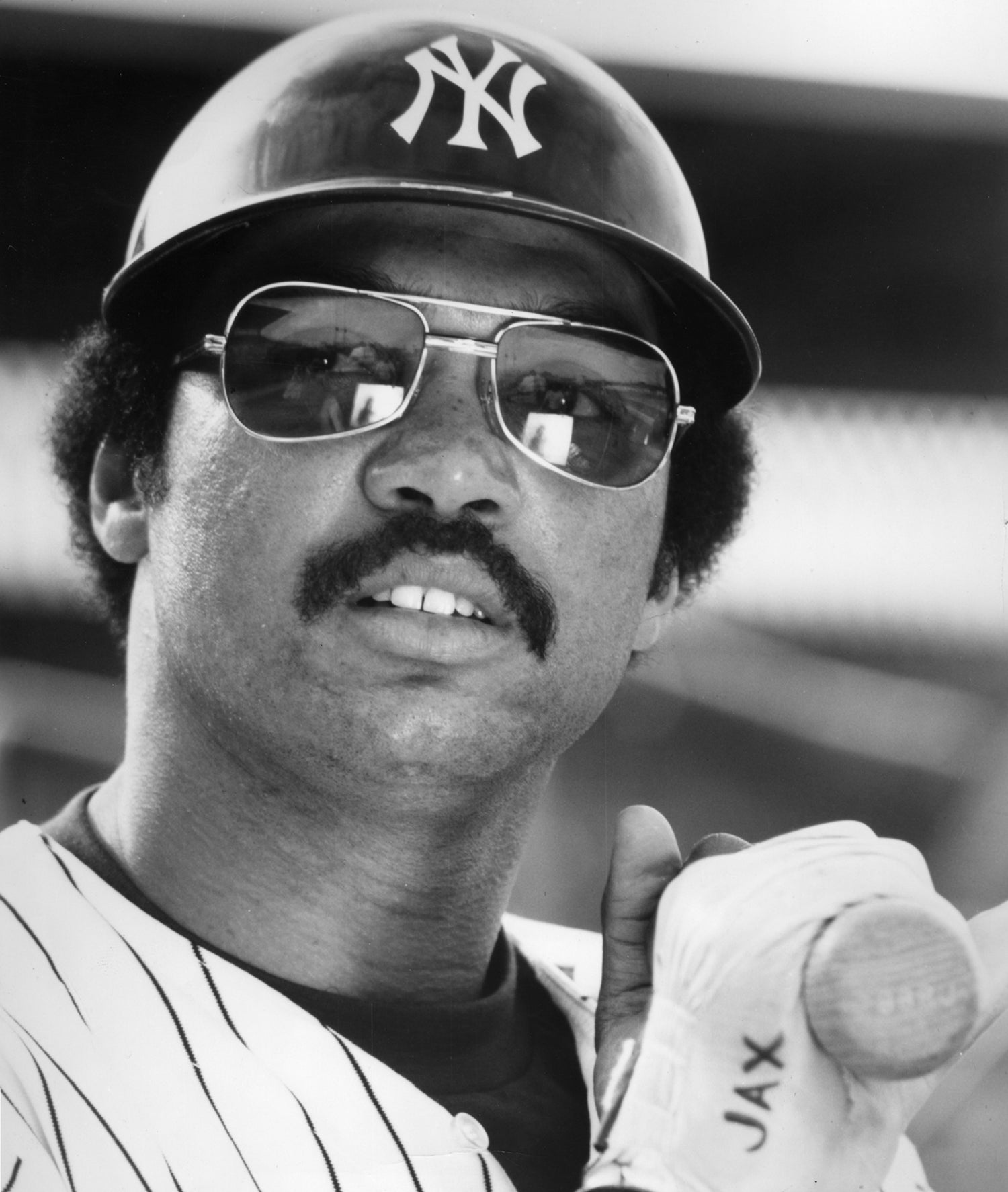

In 1973, the Oakland A's traded Dave Duncan and outfielder George Hendrick to the Cleveland Indians for catcher Ray Fosse and utility infielder Jack Heidemann. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Under Duncan’s guidance in 1981, the Indians’ team ERA dropped by nearly a full run, but the organization allowed him to leave and take the same job with the Seattle Mariners. Once again, Duncan had an impact, as the Mariners’ staff ERA fell by nearly half a run.

Duncan brought a revolutionary approach to the pitching coach job. He kept comprehensive records on every opposing hitter, so that his pitchers would be supplied with the proper information. He also drew rave reviews for his ability to relate to pitchers on a personal level, somehow finding a way to reach a wide array of personalities.

After the 1982 season, Duncan asked for a raise from the Mariners, an understandable request. Mariners management turned him down. White Sox manager Tony LaRussa, Duncan’s onetime teammate in the A’s’ organization, then approached Seattle manager Rene Lachemann, asking him for permission to talk to Duncan. Lachemann approved the request, clearing the way for Duncan to sign on with the White Sox at a salary of $50,000.

Led by LaRussa and Duncan, the White Sox won the American League West in 1983. Under Duncan’s tutelage, several young White Sox pitchers blossomed, including staff ace LaMarr Hoyt, Richard Dotson, Floyd Bannister, Britt Burns and reliever Salome Barojas.

Over the next three seasons, the White Sox failed to match the success of the 1983 campaign. Early in 1986, Sox general manager Hawk Harrelson made the decision to fire both Duncan and LaRussa. It did not take long for the tandem to find work. Only three weeks later, the two were simultaneously hired by Duncan’s original team, the A’s. With Duncan installed as pitching coach and LaRussa as manager, the A’s were primed to dominate the American League West in the late 1980s. In particular, Duncan transformed right-hander Dave Stewart, making him into a top-flight starter. Under the regime of LaRussa and Duncan, the A’s won three consecutive pennants, culminating in a world championship in 1989.

Duncan would continue his work as a pitching guru with the St. Louis Cardinals, where he once again joined LaRussa. He remained with the Cardinals through the end of the 2011 season, helping St. Louis bring home a world championship in his final season with the franchise.

With his wife seriously ill with cancer, Duncan took a leave of absence. Jeanine Duncan succumbed to the illness in 2013, leaving behind Dave and their two sons, former major leaguers Chris and Shelley Duncan. Dave has since returned to the game on a part-time basis, working as a pitching consultant to the Arizona Diamondbacks.

In some ways, Duncan’s career has been one of changed expectations. As a bonus baby, he was expected to become a star catcher with the Kansas City A’s. That never happened, but he settled for a respectable career as a sometime starter and frequent backup. As a pitching coach, no one seemed to expect much from the career catcher. Nearly 40 years later, Duncan has forged a reputation as one of the greatest pitching coaches in the history of the game, right along with the legendary likes of Johnny Sain and Leo Mazzone.

Dave Duncan has certainly come a long way from 1968, when he wore that funny-looking two-toned cap on that strange Topps baseball card.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum