- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1968 Topps Don Wilson

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Don Wilson

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Baseball cards provide us with context.

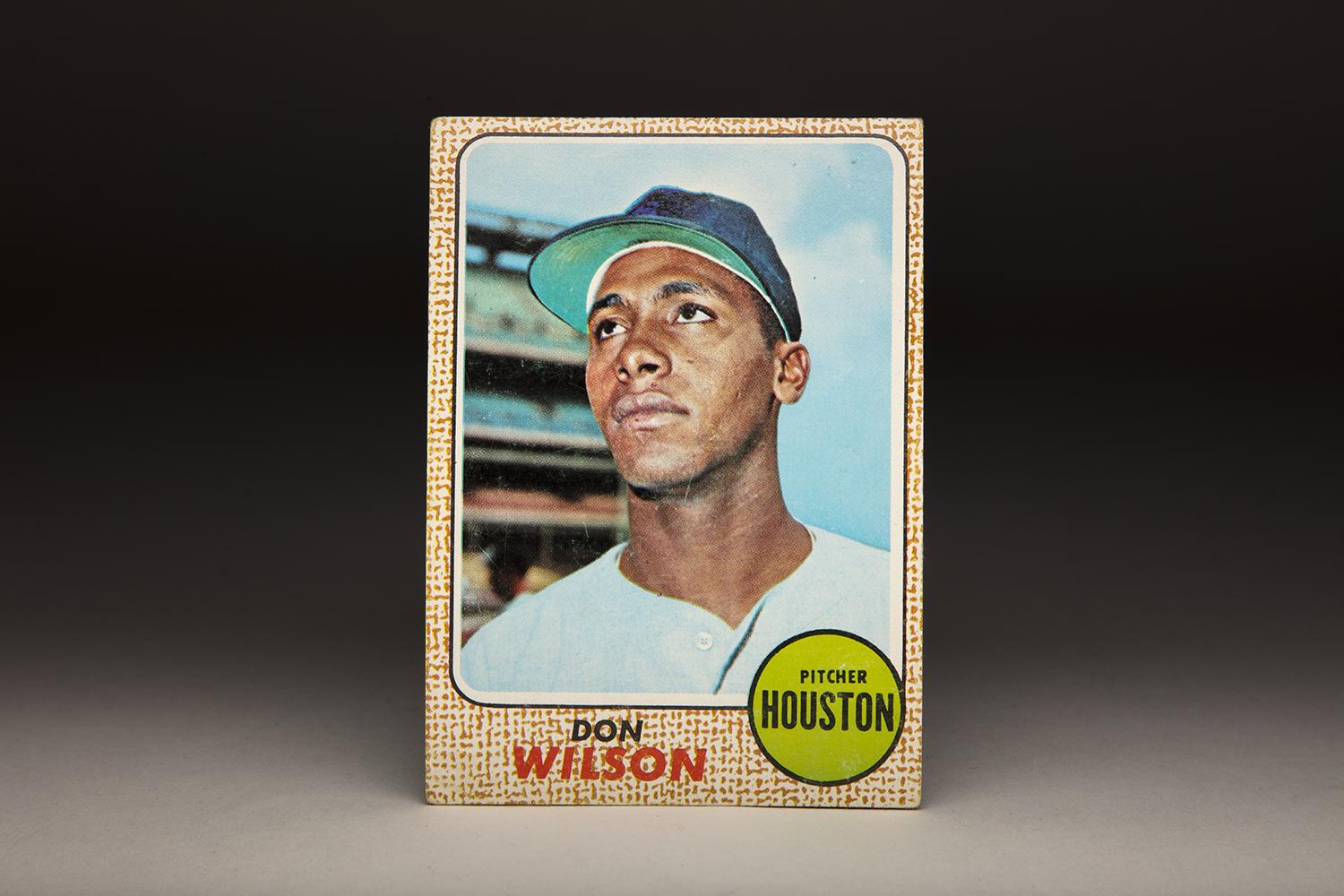

When the photo for Don Wilson’s 1968 Topps rookie card was taken, almost certainly during the 1967 season, he was in the midst of his first full season in the big leagues. On this day, the weather in Queens looks like a mix of clouds and sun, as Wilson poses at Shea Stadium prior to a game against the New York Mets. Wilson is wearing the Houston Astros’ road uniform of this time period, but his cap has clearly been airbrushed. Why? With the Astros in the middle of a dispute with the Monsanto Company (producers of Astro Turf) over the use of the name “Astros,” the Topps Company decided not to take a risk by showing the Astros logo.

Topps did this with a number of Astros players in its 1968 and ’69 card sets; by 1970, the dispute came to an end, making Topps feel safe to start showing the logo and nickname of the Astros on its cards.

All of that is fine and well, and hopefully accurate, but I’m more interested in Wilson himself. He is very young, and appears very lean, in this photograph. He was only 22 at the time, a fresh-faced youngster with the promise of a long career. A closer look at Wilson’s face provides us with some sense of his mood. He looks a little worried, perhaps a bit intimidated. That’s understandable, given his youth. Being all of 22, being a rookie, and playing in New York City, can be a bit daunting for just about anybody.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Of course, I could be reading far too much into Wilson’s expression. Perhaps the Topps photographer simply caught him at an odd moment. Who knows exactly what any player is thinking at the second that his picture is being taken for his first baseball card? Then again, Wilson’s story makes us wonder. His career would include several moments of controversy. Some called Wilson a troubled young man. And less than a decade after Wilson first appeared on a Topps card, he would be gone, taken away short of his 30th birthday, for reasons that remain somewhat mysterious and unsettled to this day.

Here’s what we do know. Wilson was part of a flock of talented right-handed pitchers who came through the Astros’ system in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Larry Dierker came up to the Astros at the same time as Wilson. Dierker and Wilson would soon be followed by Tom Griffin and Ken Forsch, and then a young J.R. Richard, who would become the best of the bunch. Wilson was a smaller version of the towering Richard. At 6-foot-2, Wilson couldn’t match Richard’s 6-foot-8 height, but his fastball was just as good. The Astros believed that he would become a No. 1 starter and stay that way for a long time.

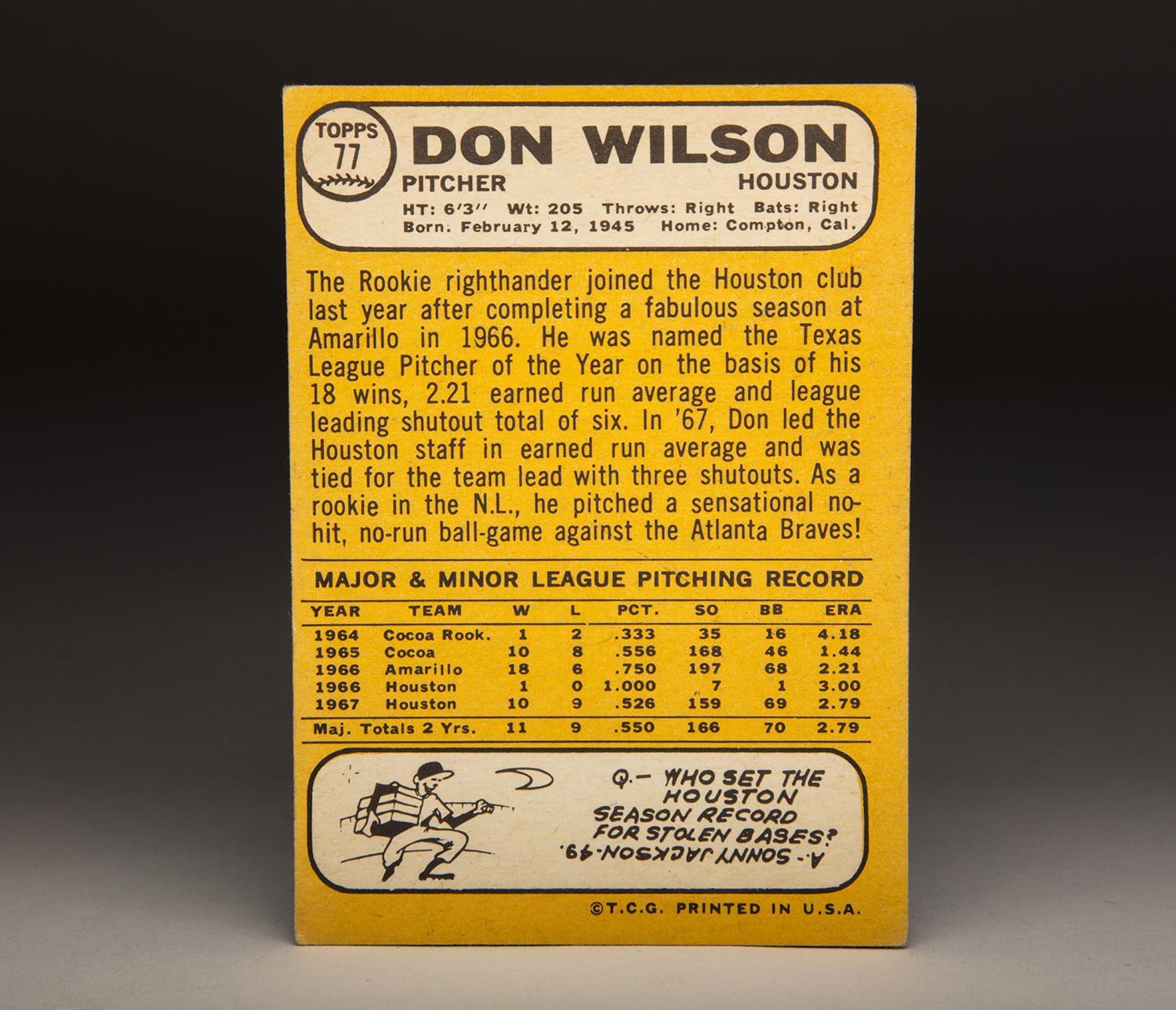

Four years before his 1968 Topps card hit stores, Wilson signed as an amateur free agent with the Houston organization. That’s when the team was still known as the Colt .45s, a nickname that would give way to Astros in 1965. Wilson spent parts of three seasons in the Houston system. After a rough debut in the obscure Cocoa Rookie League, he moved up to the Florida State League in 1965. Spinning an ERA of 1.44, he completely dominated the competition. Then came a promotion to Double-A Amarillo in 1966. Wilson won 18 games while striking out 197 batters in 187 innings. So impressed by his annihilation of the competition, the Astros decided that he should bypass Triple-A ball altogether. They called him up late in 1966, giving him a one-game cameo out of the bullpen. Wilson pitched six innings in relief that day, allowing two runs while striking out seven.

With his riding fastball and sharp slider, Wilson was more than ready for the National League. The Astros made him a fulltime starter in 1967, giving him 28 starts as part of a rotation that featured veterans Mike Cuellar, Dave Giusti and Bo Belinsky. Wilson’s 2.79 ERA led the staff. He also won 10 games, including his first career no-hitter, while striking out 159 batters in 184 innings.

Given the conditions of the Year of the Pitcher in 1968, Wilson should have been even more dominant, but his ERA rose to 3.28 that summer. Wilson lost 16 games that season, mostly because of a lack of run support from a last-place Astros team. One of the bumps to the season came in early August, when he faced the Philadelphia Phillies at the Astrodome. Wilson was pitching well that day, but was hampered by chest pains, which had been bothering him in recent weeks. The Astros removed him in the eighth inning and sent him to a local hospital, but tests showed no significant problems.

In 1969, Wilson started to gain some national prominence, in part for reasons that had little to do with baseball. An open-minded young man of high intelligence, Wilson drew some attention when he and teammate Curt Blefary became roommates on Astros road trips. The two, who were already good friends, became the first regularly paired interracial roommates in the history of the National League. In an interview with the Fredericksburg Free-Lance Star, Wilson told a reporter that he had received hate mail about the situation.

“It’s just hard for them to get it through their heads that we are just two human beings trying to make a living in the same game.”

On the field, Wilson dominated hitters at times, striking out 235 batters in 225 innings. He was never better than he was on the first day of May, when he fired a no-hitter against the Cincinnati Reds. The no-hit performance was especially satisfying given the hard feelings between the Astros and the Reds, two rivals in the newly formed National League West. Wilson claimed that Reds manager Dave Bristol had taunted him during the game, even calling him “gutless” at one point. Wilson also claimed that some of the Reds’ players stuck their tongues out at him. At the end of the game, Wilson tried to charge the Reds’ dugout, but several of his teammates held him back. “I never wanted anything so bad in all my life as to pitch that no-hitter,” Wilson told Earl Lawson of the Sporting News.

As well as Wilson pitched in 1969, he did face a roadblock of sorts. It was Harry Walker’s first full season at the helm of the Astros. Although Walker enjoyed some success as manager, he also had a reputation for having difficult relationships with some of his African-American players, including Joe Morgan and Jimmy Wynn. Walker clashed with Wilson, too. At one point, Wilson had to be restrained from throwing a punch at Walker.

In spite of the tension, Wilson pitched well for Walker. In 1969, he won 16 games. In 1970, he bounced back from tendinitis in his elbow to finish the season in strong fashion. And then in 1971, he earned a berth on the All-Star team, posted the lowest ERA of his career (2.45) and earned everlasting praise from Walker, who predicted that Wilson would become an even better pitcher over the next half-decade.

That never quite materialized. Wilson would continue to pitch at the level of a quality No. 2 starter, but never quite broke through to the level of superstardom. He never won 20 games, which was long a goal of his, and never experienced that breakout season. He also continued to clash with his managers, at first Walker and then Leo Durocher, who became Houston’s skipper in the middle of 1972. Off the field, Wilson became increasingly outspoken. His defenders said he was simply expressing his opinion, while others felt he was becoming increasingly bitter about attitudes within the game. At times, he was simply unwilling to defer to authority; while such an attitude would not have batted an eyelash in today’s game, it ran contrary to the conservative baseball establishment of the early 1970s.

Wilson put up another solid season in 1974, winning 11 games for a .500 Astros team. Perhaps the most memorable moment of the season came on Sept. 4, when he pitched a no-hitter over the first eight innings but was removed for a pinch-hitter by manager Preston Gomez. Some observers predicted that Wilson would explode in fury over the move, but he remained calm and even-tempered, defending Gomez during postgame interviews.

When the Astros left the clubhouse after the regular season finale in 1974, no one knew that Wilson would never make it to Spring Training in 1975. Something unexpected and horrific would take place during the winter. According to some, it was an accident. Others contend that it was not. On Jan. 5, 1975, Wilson’s wife, Bernice, called a friend to say that Don was sleeping in the family car, a Ford Thunderbird, which was left running in the house garage. The friend told Bernice to call an ambulance. When the medics arrived, they found Wilson’s body in the passenger seat of the car. The carbon monoxide from the car not only killed Wilson, but it also took the life of his son, Alex, who had been sleeping in the family master bedroom above the garage. In the meantime, Wilson’s daughter, Denise, was found unconscious and would remain in a coma for several days. (Thankfully, she would recover, but she did suffer some brain damage as a result of exposure to the carbon monoxide.)

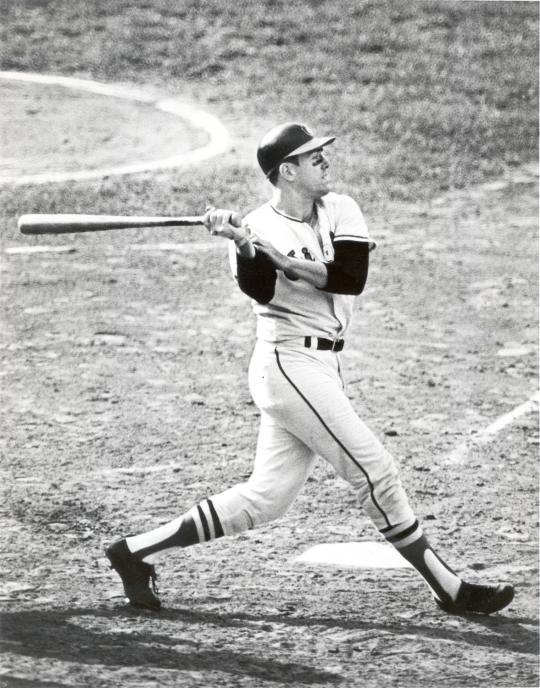

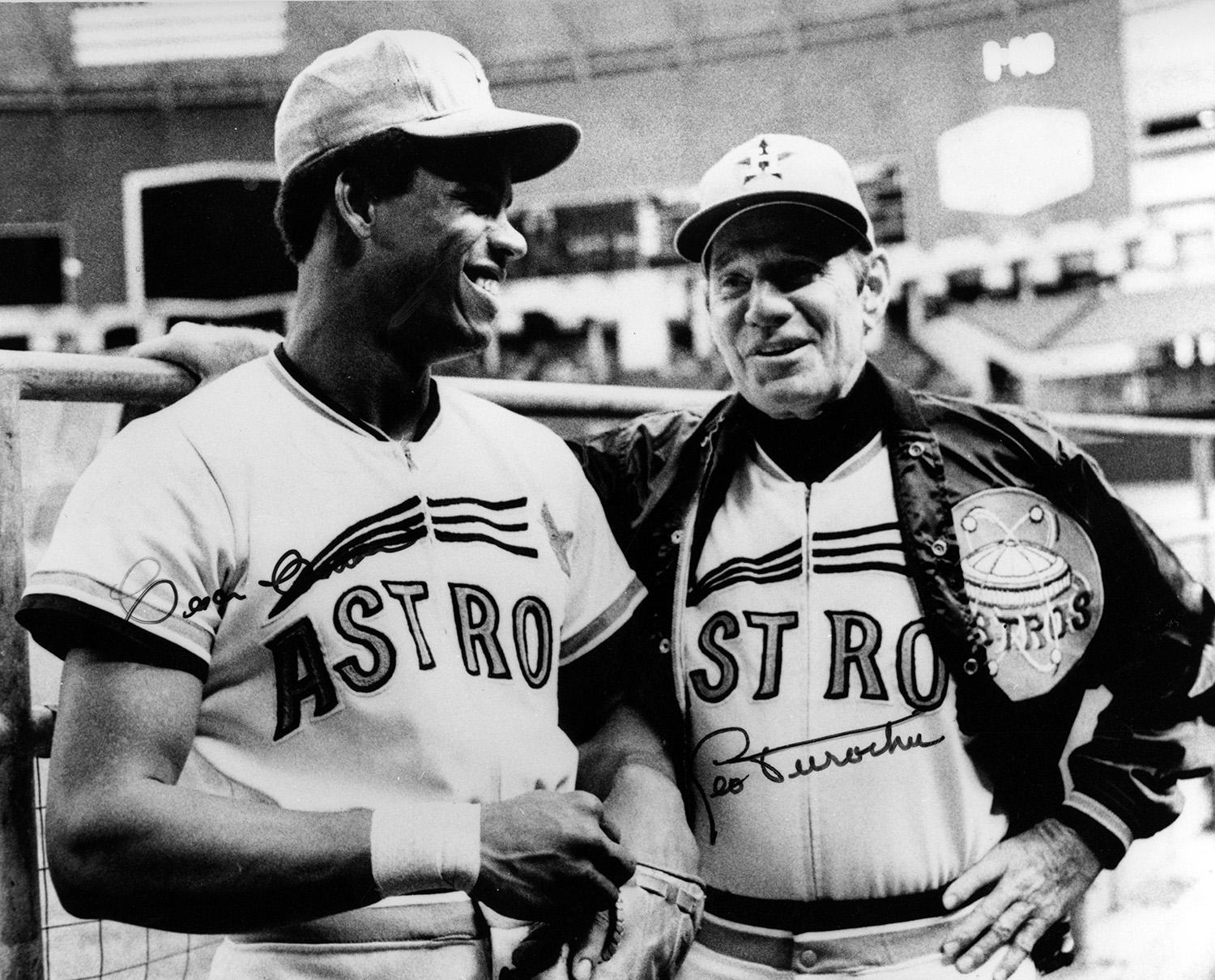

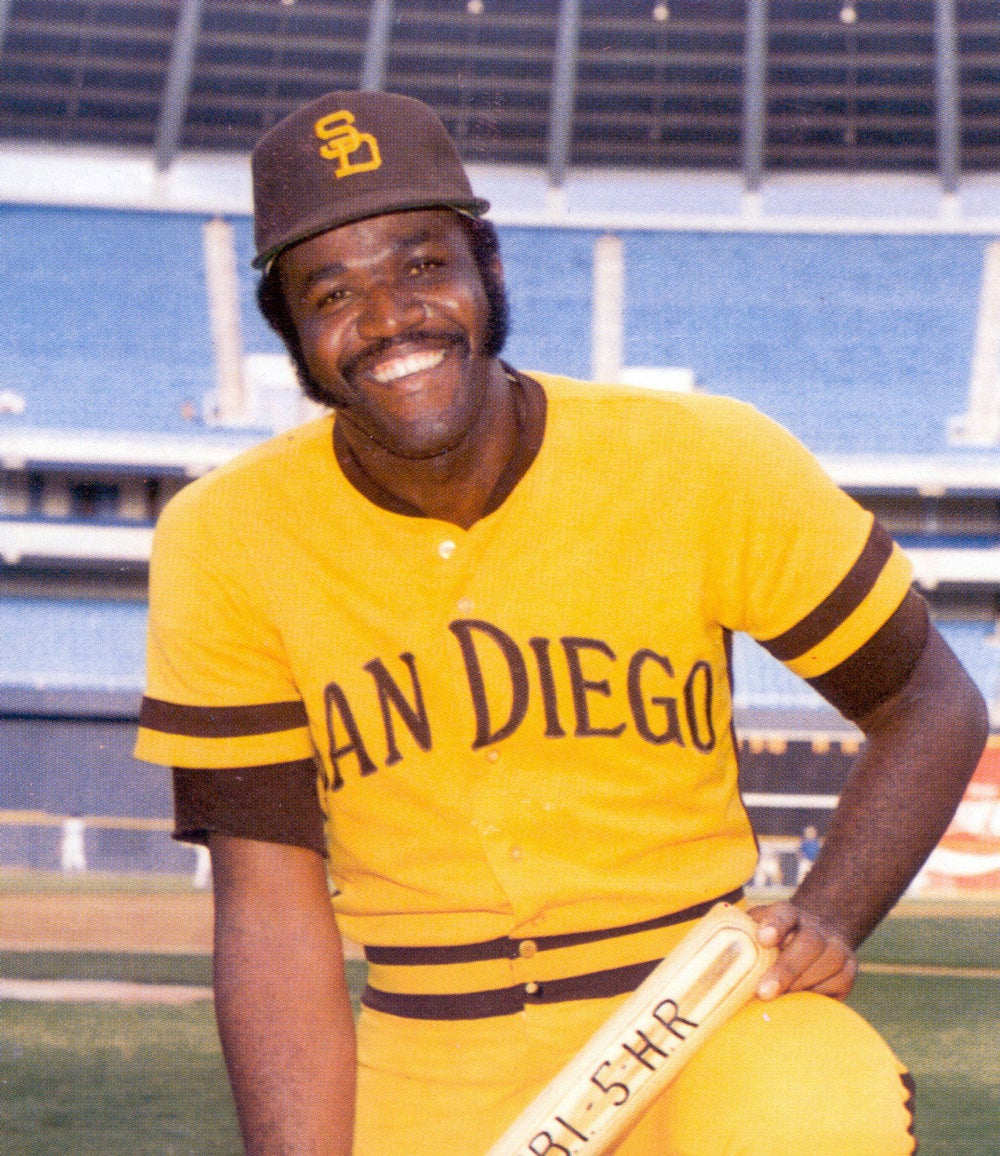

Curt Blefary (pictured above) and Don Wilson were the first regularly paired interracial roommates in the history of the National League. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

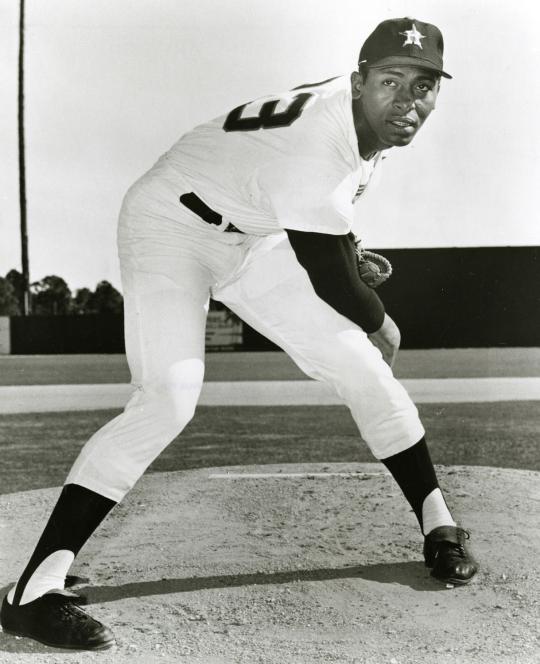

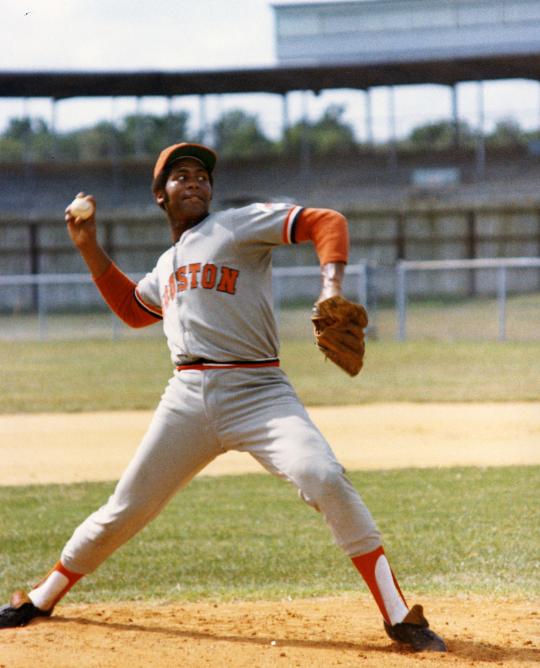

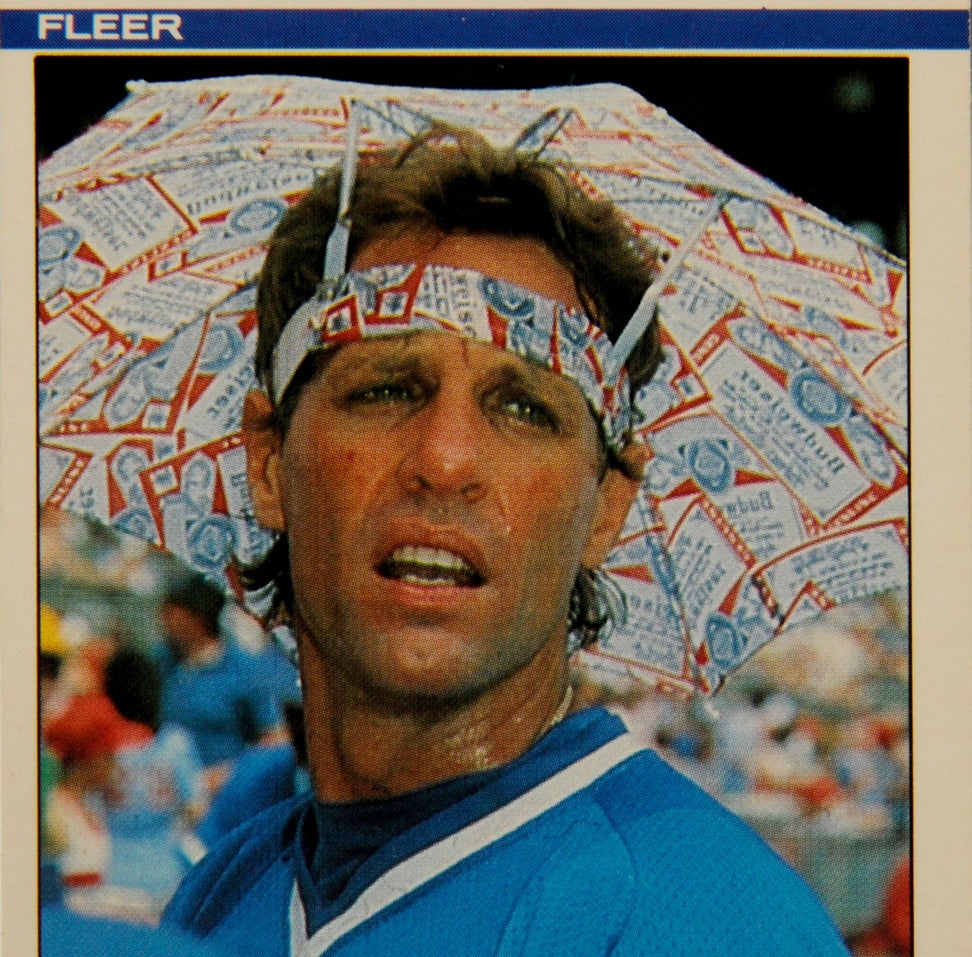

Pitcher Don Wilson joined the Houston Astros in 1966 and would remain with the team for nine seasons. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Authorities also found Bernice with bruises and swelling on her face. Police asked her what had caused the bruising, but her answers seemed to change every time she was asked about it. She denied any domestic problems between herself and Don. Neighbors who were also asked about the situation claimed that they had never heard of any arguments or fights involving the couple. Still, the police wondered about their relationship. They also questioned why Wilson and two of his children had suffered from the effects of carbon monoxide poisoning, but Mrs. Wilson had not.

Initially, the media reported Wilson’s death as a suicide. Because of those initial reports – and because I was all of 10 years old and not exactly a dogged reader or researcher at the time – I had always assumed that Wilson had taken his own life. As a result, Wilson appeared to be somewhat of a villain, if only because his recklessness had claimed the life of one of his innocent children.

Many years later, I started looking through Wilson’s file here at the Hall of Fame Library. I read one article that referred to the official coroner’s report on his death. In a report filed on Feb. 5, 1975, the coroner officially listed the deaths of Don and Alex Wilson as accidental, and ruled out suicide. That determination officially closed the case.

I had never heard any of this prior to reading it in Wilson’s file. I didn’t quite understand how the coroner came to the conclusion of an accidental death, but if it happened to be accurate, then it placed Wilson in more sympathetic territory.

Then I looked a little further into the file. I read that Wilson had a drug alcohol level of .167, above the legal driving limit of .100, at the time of his death. The coroner’s report began to make more sense. Putting two and two together, it appeared that Wilson had been drinking heavily and had fallen asleep in his car while the engine was still running. Wilson still came across as irresponsible, his behavior leading to the death of his son, but the entire incident took on the tone of being accidental, and not purposeful.

Several of Wilson’s Astros teammates came to his defense. Third baseman Doug Rader and pitchers Tom Griffin and Dave Roberts all said that Wilson was mentally and emotionally stable, and pushed aside all suggestions of suicide. They said that Wilson had every good reason to keep living. “Don had everything going for him,” Roberts told the Associated Press. “He had it all together.” Griffin echoed the sentiment in the AP story. “I really enjoyed being around him. He was a nice person, a great person.”

The Astros’ organization as a whole gave Wilson the benefit of the doubt and took measures to honor the fallen star. That season, the Astros retired Wilson’s No. 40 and wore a memorial patch on their jerseys for the entire summer. The franchise continues to honor Wilson to this day. A plaque lauding him hangs at Minute Maid Park, part of the Astros’ Wall of Honor.

Forty years later, I’m still left mystified by the Wilson story. It’s hard to know exactly how to feel. If the coroner’s report is true, then Wilson does become more sympathetic, though one can still can criticize him for being reckless. If Wilson did commit suicide, one wonders why he did so? And was Wilson responsible for the bruising that was found on his wife’s face? The answers are hard to find.

No matter the reasons behind his death, the story remains a sad one. The tragedy, in some ways reminiscent of the 2016 death of Jose Fernandez, resulted in the loss of one of the game’s young pitching stars. Wilson, who had not yet turned 30 and remained in possession of a strong, sound throwing arm, appeared to have a long career ahead of him. Who knows how much more success he would have had.

Sadly, as is the case with Jose Fernandez, that is a question to which we will never know the answer.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame