- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1988 Topps Cecil Fielder

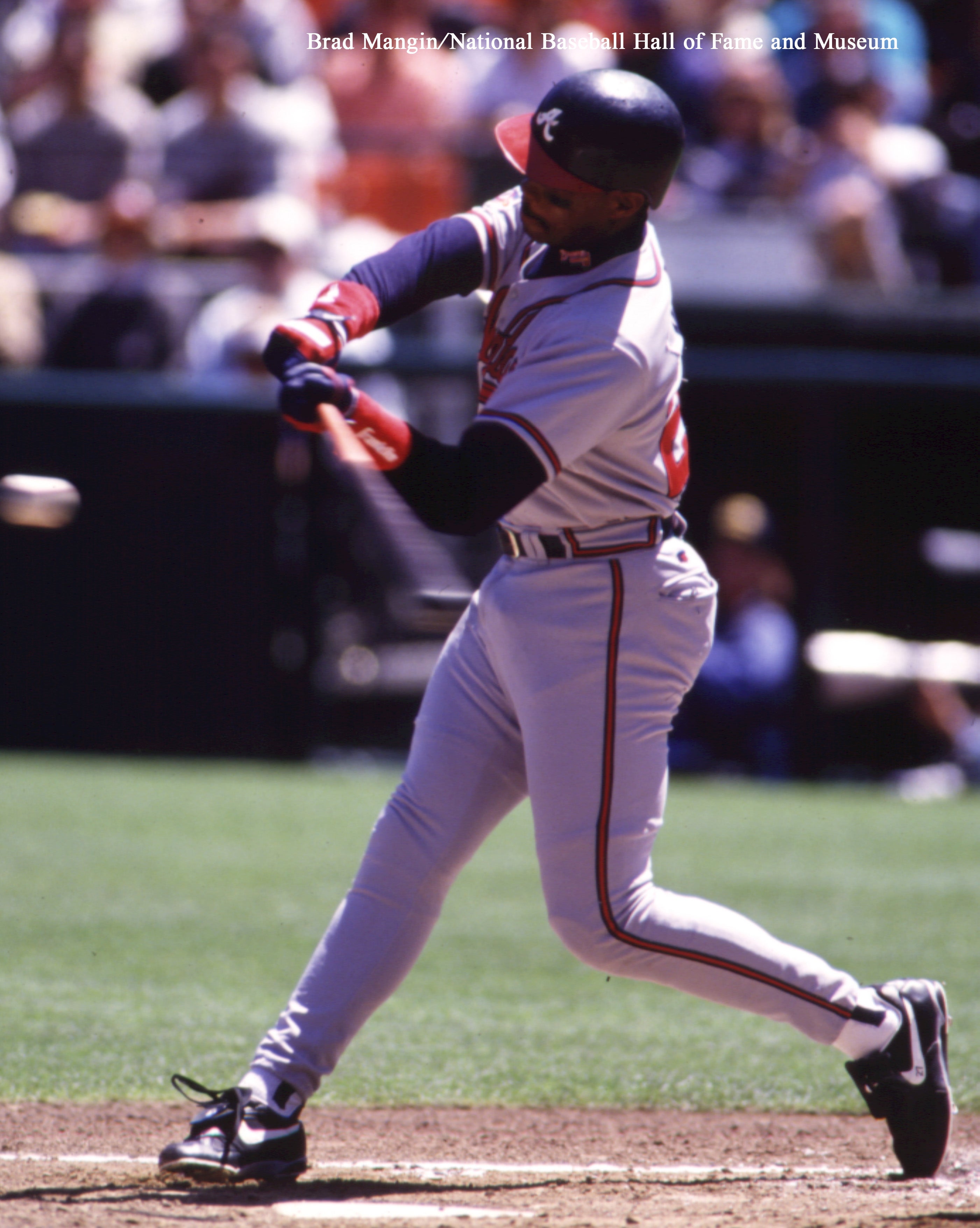

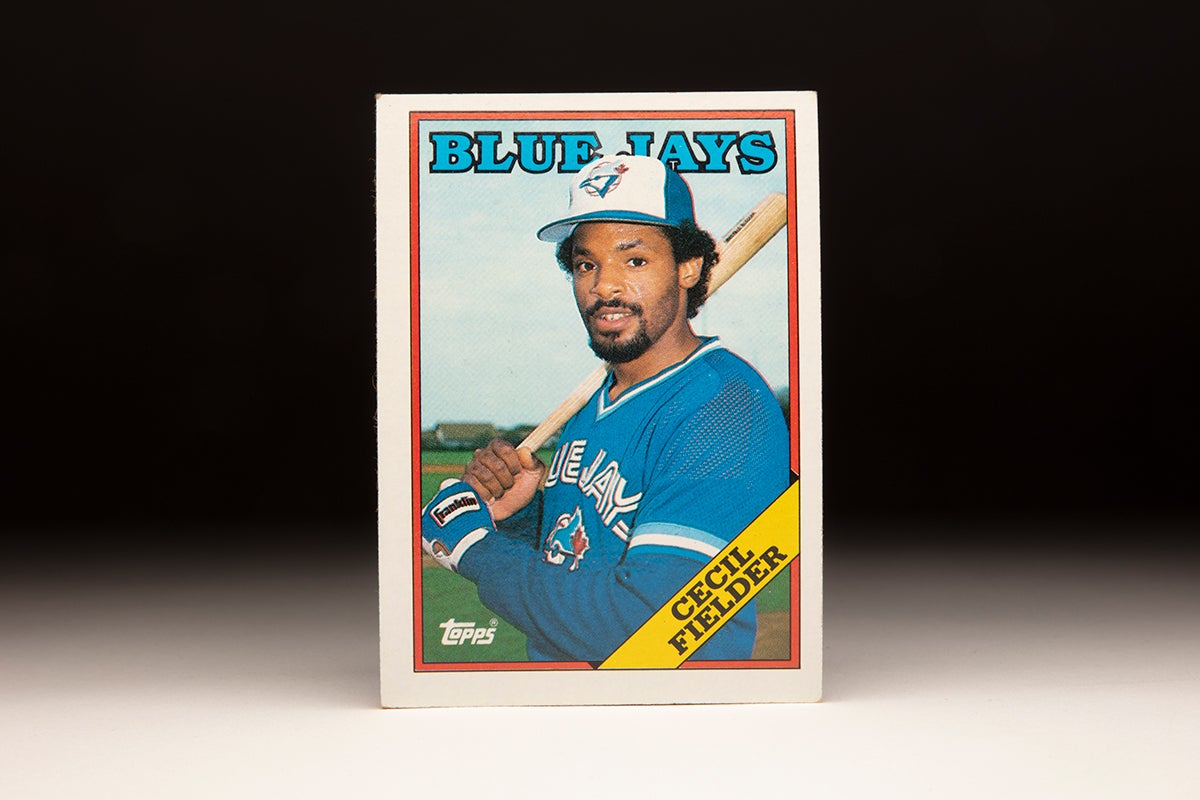

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Cecil Fielder

When the final day of the 1990 regular season dawned, 12 full years had passed since a major leaguer had hit 50 home runs in one season. It marked the longest gap between 50-homer seasons since Babe Ruth inaugurated the 50-homer club in 1920. Some thought the mark was unreachable.

Then along came Cecil Fielder, powerful former basketball and football star who had struggled with the Blue Jays before playing a season in Japan.

Few players had ever shocked the game like the Detroit Tigers first baseman.

Cecil Grant Fielder was born Sept. 21, 1963, in Los Angeles. He was named after an uncle but with a different pronunciation – one that mimicked the movie producer Cecil (Sess-sill) B. DeMille. His father, Edson, was a talented amateur athlete who encouraged his son to participate in sports before he even was old enough for school.

But Cecil was so advanced physically for his age that he often was unable to play in leagues with children his own age.

At the age of nine, Fielder was rejected by the West Covena Pop Warner League because he was too heavy.

“They told me I couldn’t play because I was too big, I might hurt the other kids,” Fielder told the Toronto Star in 1985. “You know how things bother you when you’re a kid. That bothered me a lot because I wanted to play football real bad.”

Fielder eventually became middle linebacker at Nogales High School in La Puente, Calif., and also excelled on the basketball court – dreaming of a career with the Los Angeles Lakers.

“If I was six inches taller,” Fielder told the Los Angeles Times in 1998, “I would have had the chance.”

A baseball career didn’t seem to be in the cards until his father intervened.

“I guess baseball seemed kind of slow to me,” Fielder told the Star, noting that he stopped playing in high school after his freshman year. “It was tough enough academically playing two sports.

“But (his father) said: ‘Son, you can make a lot of money playing baseball.’ He also said there weren’t the injuries there are in football. I told him I really didn’t have any desire, but he said that would come.”

Fielder returned to his high school baseball team as a junior and hit .509 while earning All-State honors in baseball, basketball and football. By that point – even though he was recruited by top college football programs throughout California – Fielder had decided that baseball was his future.

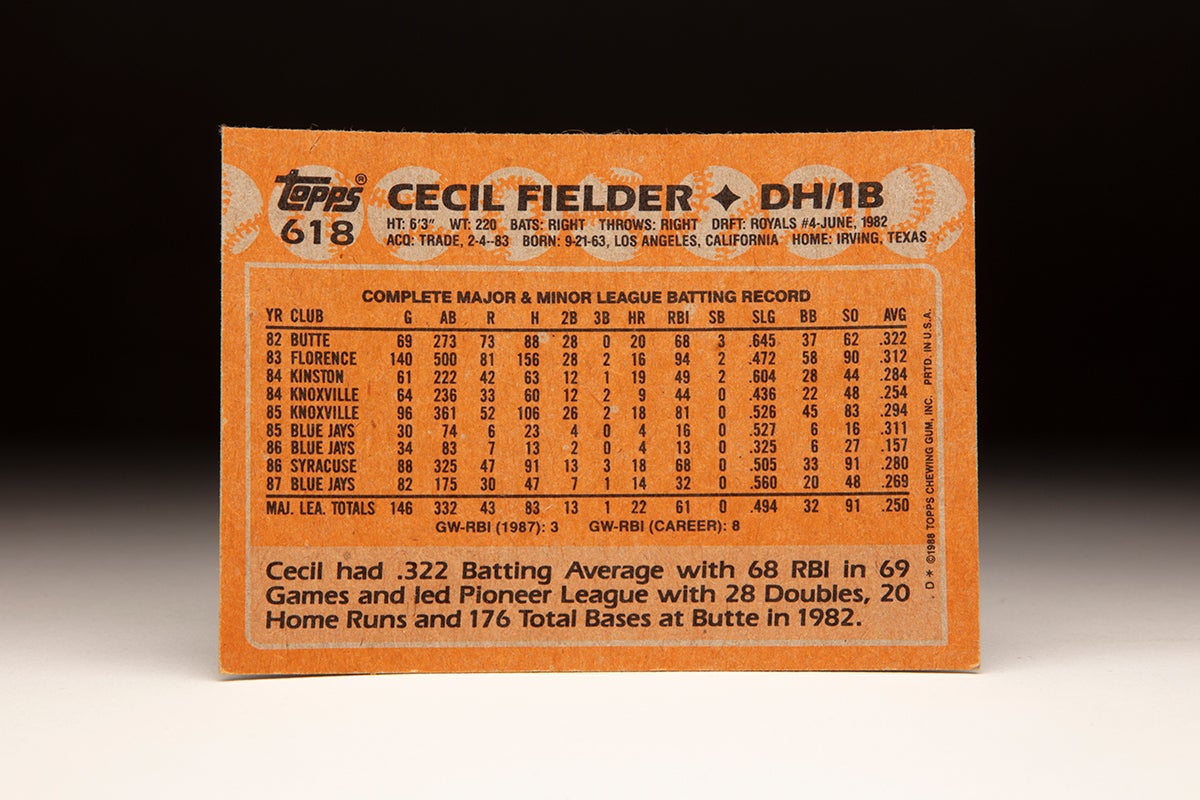

He was selected by the Orioles in the 31st round of the 1981 MLB Draft but decided to enroll at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. He stayed only part of one year before transferring to a junior college back in California. On June 7, 1982, the Royals selected Fielder in the fourth round of the June secondary draft for college players. Fielder signed and reported to Butte of the Pioneer League, where he hit .322 with 28 doubles, 20 home runs and 68 RBI in 69 games.

Fielder already weighed more than 220 pounds and had not yet turned 19 years old.

“The last thing Cecil needs is another free steak dinner,” Butte manager Tommy Jones told the Montana Standard after Fielder hit two doubles and a homer – earning a free supper from a local sponsor – in a game against Calgary on July 4.

Fielder was named to the Pioneer League All-Star team as a designated hitter, leading the league in homers and doubles while finishing second in RBI.

“He’s got to be considered in the top five prospects in all of baseball in Class A and rookie leagues in America,” Jones told the Standard. “He’s just getting better and better.”

But the Royals were reportedly worried about Fielder’s weight. On Feb. 5, 1983, he was traded to the Blue Jays in exchange for veteran outfielder Leon Roberts.

“I did real well, but the Royals told me they needed an extra outfielder for the big league team, and Toronto said they wanted either me or Joe Citari,” Fielder told the Kansas City Star in 1990. “I guess they felt a little bit easier about giving me away because Joe was a good ballplayer also.”

Citari, however, never made it past Triple-A and was done playing by the time Fielder was starring for the Tigers in 1990. Roberts, meanwhile, batted .252 with eight homers over 112 games with the Royals in 1983 and 1984 before his career ended.

Fielder had another strong season with Class A Florence of the South Atlantic League in 1983, hitting .312 with 16 homers and 94 RBI. But he weighed 245 pounds at the end of the season, prompting his winter ball manager Jose Martinez to suggest he begin a running program.

By the end of the 1984 season – which he split between Class A Kinston and Double-A Knoxville, the 6-foot-3 Fielder was back to 225 pounds. He hit 28 homers and drove in 93 runs in his two stops in the minors that year and returned to Knoxville to begin the 1985 season.

“He always had potential,” Blue Jays minor league hitting instructor John Mayberry told the Kansas City Star. “He hit to all fields with power. The thing was getting him to wait for a good pitch – be patient.”

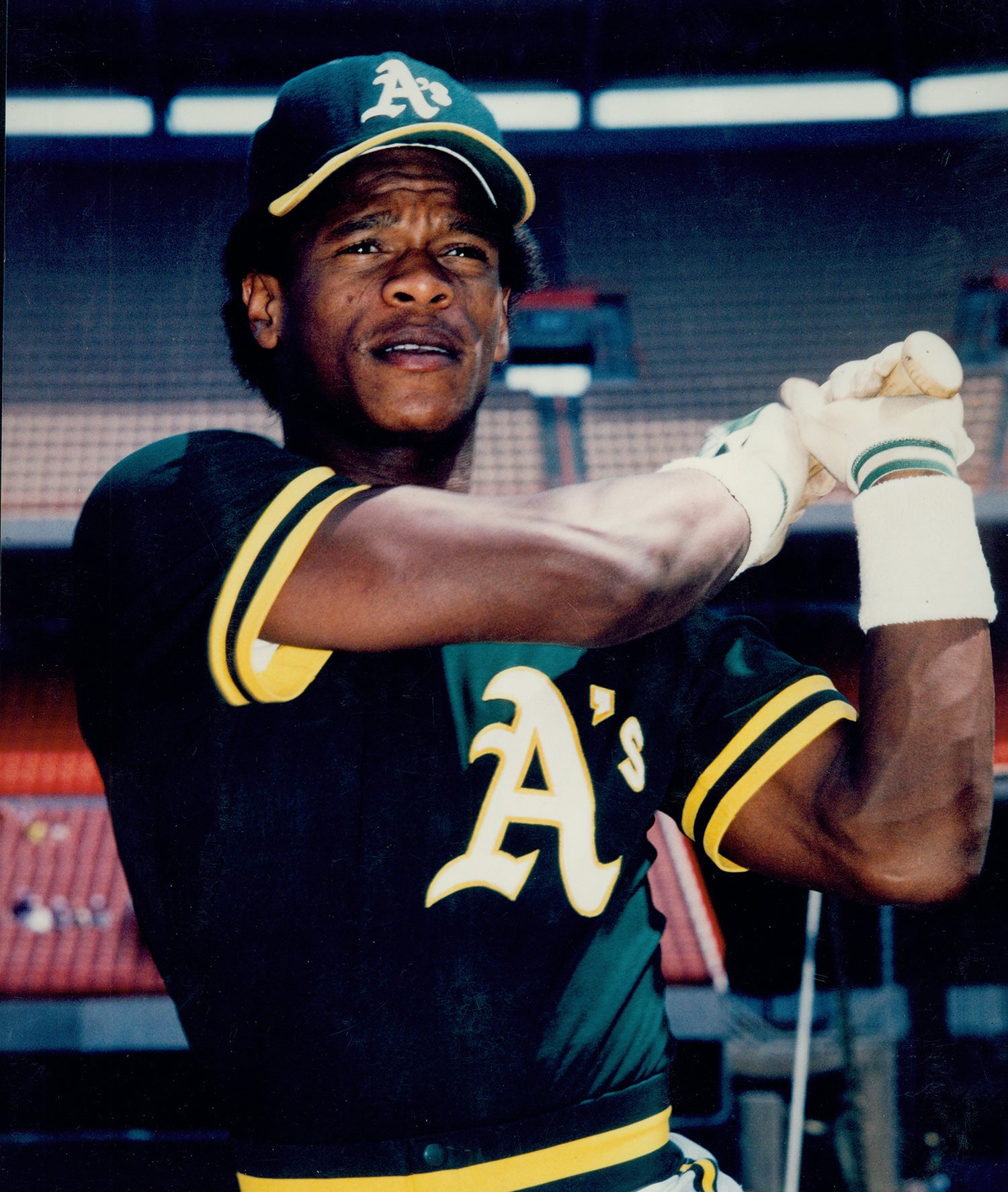

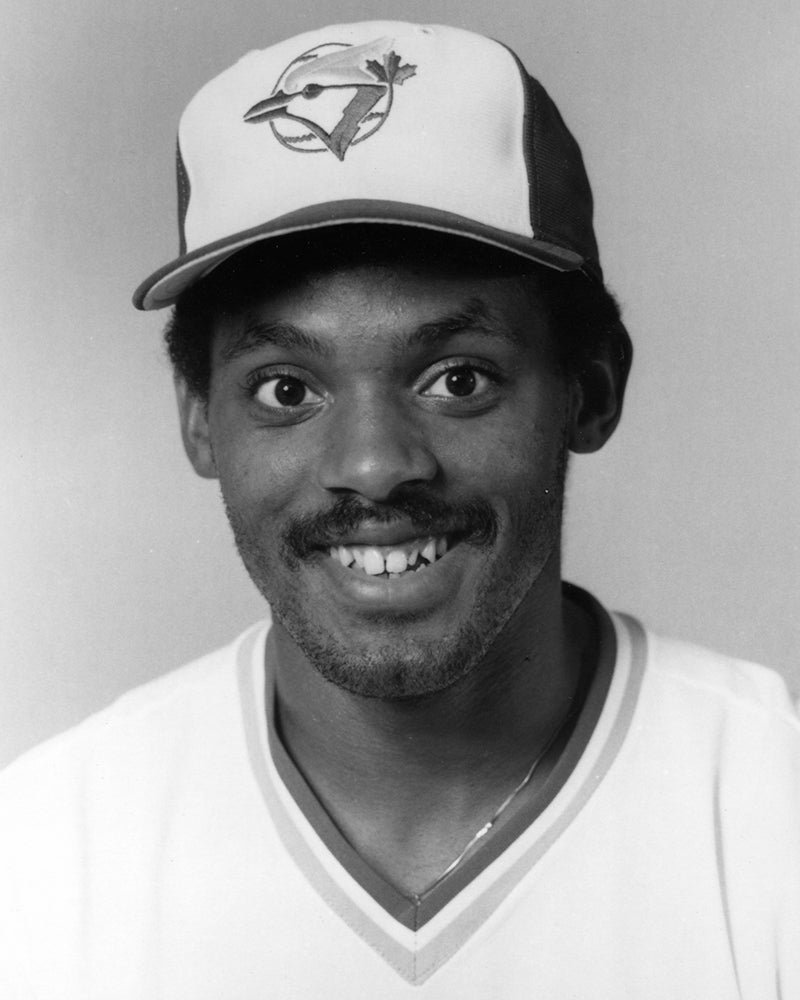

After patiently waiting at Knoxville – where he hit .294 with 18 homers and 81 RBI in 96 games – Fielder was brought to Toronto, where he made his big league debut on July 20 as the Blue Jays were fighting for the AL East title. He doubled in his first at-bat against Oakland’s Tim Birtsas and platooned at first base for much of the rest of the season with Willie Upshaw, finishing with a .311 batting average, four homers and 16 RBI in 30 games.

The Blue Jays won the division title but manager Bobby Cox went with the veteran Upshaw throughout the American League Championship Series, relegating Fielder to pinch-hitting duties. He had a double in three at-bats as Toronto lost to the Royals in seven games.

But his success in 1985 did not guarantee Fielder a big league job in 1986. With Upshaw and Cliff Johnson locks for the roster – and veteran César Cedeño also in camp in Spring Training – Fielder was fighting for a job. He put in extra work with hitting coach Cito Gaston but still was optioned to Triple-A Syracuse in May.

“It’s not my decision,” Fielder told the Toronto Star. “I can only do what I have to do.”

Fielder reportedly weighed a svelte 215 pounds that spring and spent some time in the outfield with Syracuse. He hit .280 with 18 homers and 68 RBI in 88 games in between stints with the Blue Jays, appearing in 34 games for Toronto. That same year, future Hall of Fame first baseman Fred McGriff made his big league debut with the Blue Jays.

Once again, Fielder would find himself with no clear path to regular playing time.

Upshaw was the Blue Jays’ first baseman on Opening Day in 1987 and the lefty-swinging McGriff started at DH in what became a platoon with Fielder, who appeared in 82 games that season while hitting .269 with 14 homers and 32 RBI en route to a .905 OPS. But the season ended on a sour note as Toronto – which led the AL East for most of the season – was caught and passed by the Tigers on the final weekend.

In 1988, the Blue Jays traded Upshaw to Cleveland late in Spring Training and McGriff won the first base job, leaving Fielder to platoon with left-hitting Rance Mulliniks at DH. Fielder was unable to match his 1987 numbers, batting .230 with nine homers and 23 RBI in 74 games – hitting just .192 with two homers and four RBI after the All-Star break.

With his career at a crossroads, Fielder decided to seek a fulltime job in Japan. On Dec. 22, 1988, the Blue Jays sold his contract to the Hanshin Tigers of the Japan Central League.

It proved to be a deal that turned Fielder into a history-making player.

With Hanshin, Fielder hit 38 home runs and drove in 81 runs in 106 games in 1989. He then returned to the United States on a two-year deal with the Tigers worth $3 million.

“I think being rejected – that’s what it took for him to go (to Japan) – made him feel lucky to be able to play here,” Tigers manager Sparky Anderson told the Associated Press. “I’ll tell you something, this young man is a talent.”

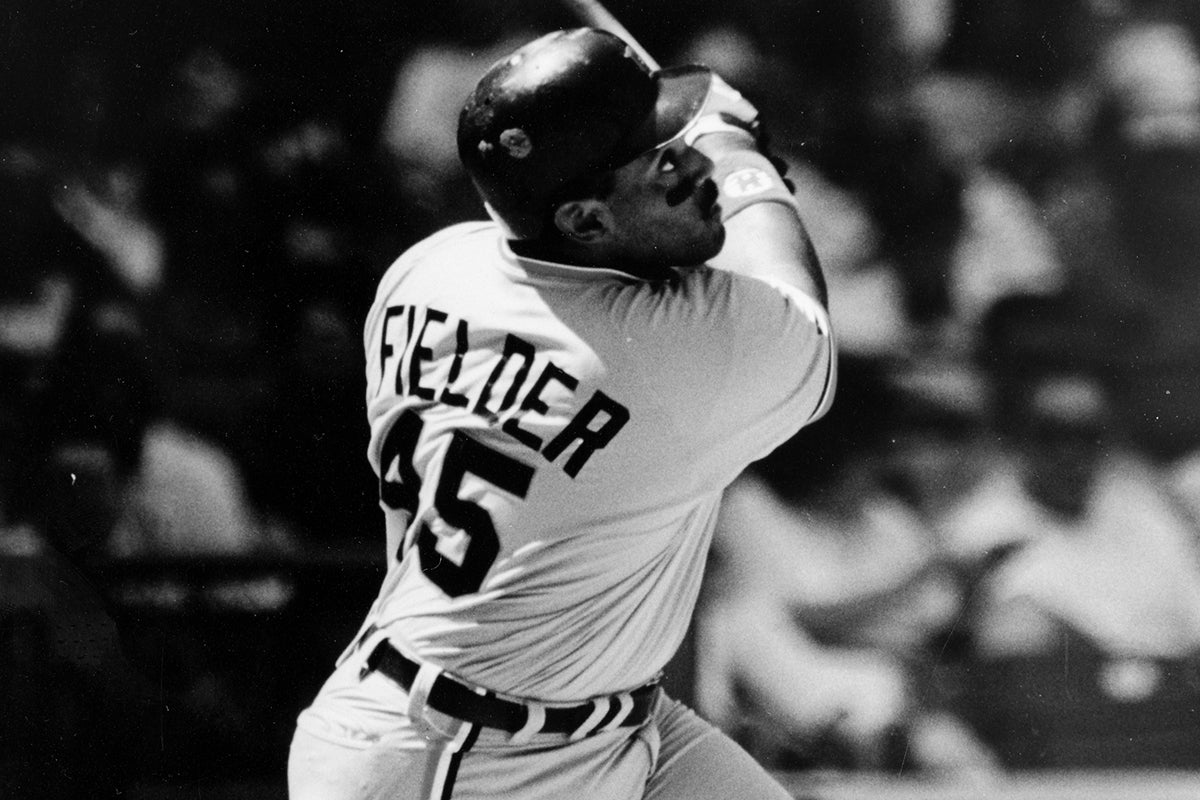

Fielder – who was still only 26 years old – started slowly in 1990 but got hot with the weather. He hit three home runs in one game against the Blue Jays on May 6, bringing his total for the season to 10. He added eight more home runs in May and eight more in June – including another three-homer game against Cleveland on June 6.

With 42 home runs entering September, Fielder became the talk of baseball. No big leaguer had reached the 50-home run mark since George Foster of the Reds in 1977 – and no American Leaguer had done it since Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle in 1961.

“He’s an angel in disguise,” Tigers hitting coach Vada Pinson told the Kansas City Star. “Thank God Japan sent him back to us.”

Fielder hit his 49th home run on Sept. 27 vs. the Red Sox, then went five games without hitting a home run. With the pressure building – the 50-home run mark seemed to many like 60 home runs does today – Anderson moved Fielder up to the No. 2 spot in the batting order on the next-to-last day of the season to get him as many at-bats as possible. But he still entered the season’s final day at 49 home runs.

He drew a walk off Yankees rookie Steve Adkins – who was pitching in his final big league game – in the first inning and lined out in the second. But in the top of the fourth against Adkins, Fielder hit a two-run home run deep to left field at Yankee Stadium to reach the magic number. He would homer again in the eighth inning off Alan Mills to finish the season with 51 home runs – becoming just the 11th player in history to reach the 50-homer mark.

“I heard what everyone was saying about Cecil Fielder and it hurt,” Fielder told the Associated Press about his motivation during the 1990 season. “They didn’t know what I could do.”

Fielder led the major leagues with his 51 home runs, 132 RBI and .592 slugging percentage while pacing the AL with 339 total bases. He also led the big leagues with 182 strikeouts, which at the time was considered something of a negative on his resume. It may have cost him some votes in the AL Most Valuable Player race, and Fielder finished second to Rickey Henderson by 31 points (317 to 286) in that balloting.

“In the past, when I felt I should have won it, I felt I got cheated,” Henderson told the AP about his MVP Award. “But if they’d given it to Cecil, I wouldn’t have felt cheated this time.”

Fielder’s weight was reported to be more than 240 pounds when he reported to Spring Training in 1991, but it had little effect on his performance. He played in each of Detroit’s 162 games that year, once again leading the AL in home runs (44) and RBI (133). He was named to his second straight All-Star Game, won his second straight Silver Slugger Award and once again finished second in the AL MVP voting – this time placing 32 points behind winner Cal Ripken Jr.

“It’s a joke as far as I’m concerned,” a disappointed Fielder told the AP after the MVP vote was announced. “The way things were done this year, I’m just done with it. If anybody put together two years like I just did, they’d be MVP. So it’s just a bunch of garbage.”

With his contract expiring, Fielder was arbitration-eligible due to the fact he had accrued less than six years of MLB service time. After asking for $5.4 million, Fielder agreed to a one-year deal worth $4.5 million – the biggest one-year contract in history. The Tigers also offered Fielder a four-year deal worth $17 million but Fielder turned that down just days before Bobby Bonilla set a new standard by signing a five-year contract worth $29 million with the Mets.

Fielder hit 35 home runs and drove in an MLB-best 124 runs in 1992, becoming the first player to lead the AL/NL in RBI for three straight seasons since Babe Ruth in 1919-21.

“It hasn’t been what I’d call a banner season all the way around,” Fielder told the AP. “But I’ve found some type of way to drive in my runs. I don’t know how I do it.”

Arbitration-eligible again following the season, Fielder and the Tigers agreed to a five-year, $36 million contract that made him baseball’s second-highest paid player – behind only Barry Bonds.

Fielder did not lead the AL in RBI in 1993 but still drove in 117 runs to go with 30 homers and 90 walks. He also continued to launch prodigious blasts – a run that started on Aug. 25, 1990, when he became the first Tigers player (and only the third overall) to clear the left field roof at Tiger Stadium. In 1993 alone, Fielder hit three home runs listed at 475 feet or better – including one measuring 484 feet.

The 1994-95 work stoppage ate into Fielder’s overall numbers but he still hit 28 home runs and drove in 90 runs in 109 games in 1994 before following that up with 31 homers and 82 RBI in 136 contests in 1995. But the Tigers had losing records in both seasons. And when Detroit was en route to a 53-109 record in 1996, Fielder requested a trade.

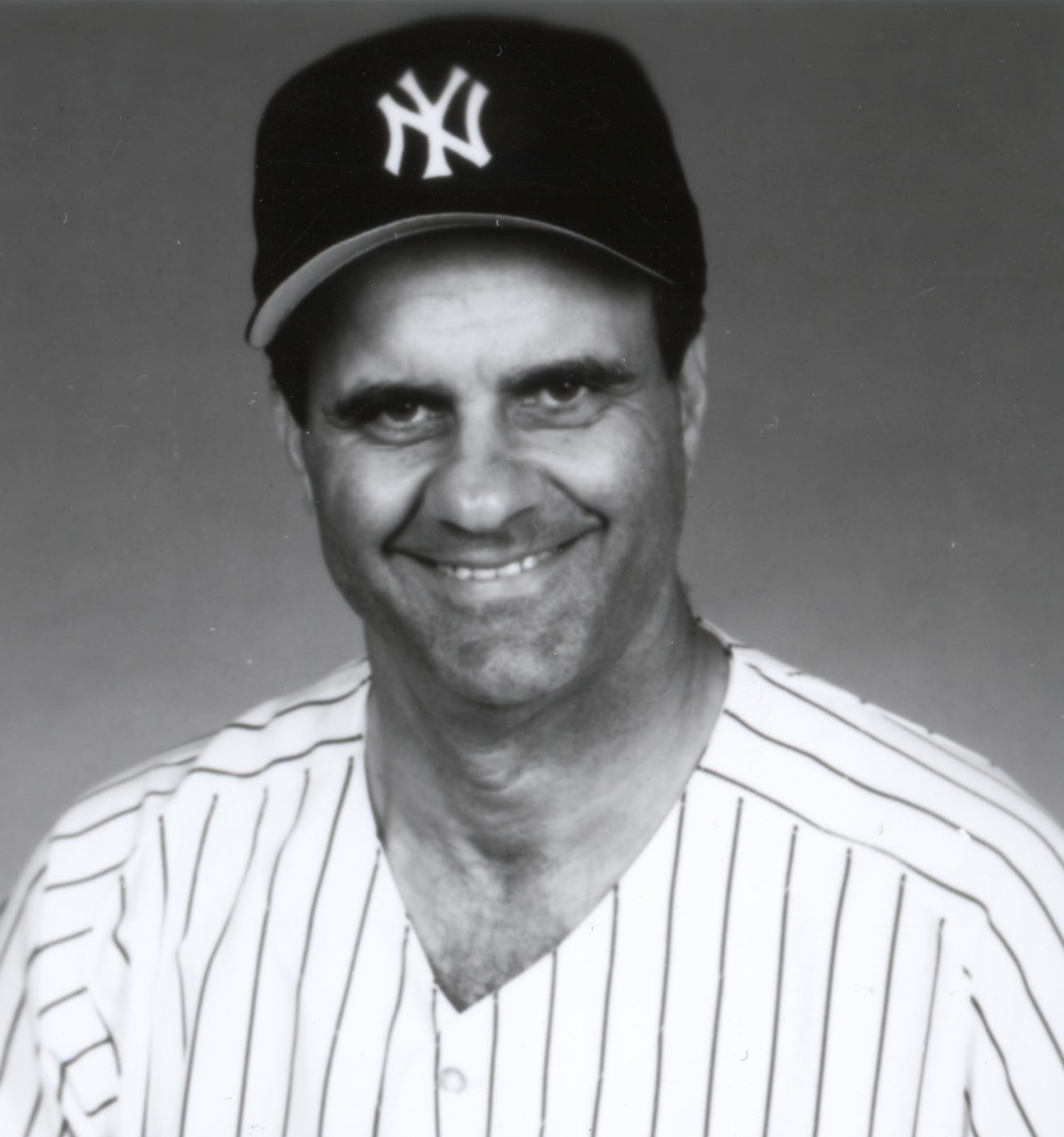

On July 31, the Tigers sent Fielder to the Yankees in exchange for Rubén Sierra, top pitching prospect Matt Drews (who never made it to the big leagues) and $1 million in cash.

“I’m shocked to be going to the Yankees,” Fielder told the Grand Rapids (Mich.) Press News Service. “I didn’t think it would be the Yankees, but I think it’s a good place to be.”

Fielder agreed to defer $2 million of his 1997 salary at the Yankees’ request. He had hit 26 home runs in 107 games with the Tigers in 1996, making him the first player in franchise history with at least 25 home runs in seven straight seasons. His 245 homers with Detroit ranked fifth in franchise history at the time of the trade.

“It’s a little weird, but I feel good about it,” Fielder said following the deal. “I’m just happy for the opportunity.”

Fielder was joining a Yankees team that was making a push for the AL East title. He gave New York everything it wanted, batting .260 with 13 homers and 37 RBI in 53 games while moving into the cleanup spot in the lineup as the team’s primary designated hitter.

The Yankees won the division and Fielder returned to the postseason for the first time since 1985. In Game 2 of the ALDS vs. Texas, he cut the Rangers’ lead to 4-2 with a fourth-inning home run off Ken Hill before tying the game in the bottom of the eighth with an RBI single off Jeff Russell. The Yankees won the game 5-4 in 12 innings to tie the series at a game apiece. After New York won Game 3, Fielder again played the hero in Game 4 – singling off Bobby Witt in the fourth inning to drive in Bernie Williams during a three-run rally that left the score 4-3 in favor of the Rangers.

Then with the game tied at four in the seventh, Fielder singled home Tim Raines with what became the decisive run in New York’s 6-4 victory that sent the Yankees to the American League Championship Series.

In the ALCS vs. Baltimore, Fielder hit a two-run homer in the eighth inning of Game 3 to give the Yankees a little breathing room in a 5-2 victory. Then in Game 5, Fielder’s three-run homer in the third inning gave New York a 5-0 advantage that became a 6-4 victory that sent New York to the World Series for the first time since 1981.

Fielder’s heroics continued in the World Series against the Braves. In Game 4, his sixth-inning single produced New York’s first two runs of the game as the Yankees clawed back from a 6-0 deficit to eventually win 8-6 – tying the series at two games. Then in Game 5, Fielder’s fourth-inning double off John Smoltz scored Charlie Hayes – who had reached on an error – with the game’s only run as New York took a 3-games-to-2 lead back to Yankee Stadium.

When New York won Game 6, Fielder had his long-coveted World Series ring. The New York chapter of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America voted him the winner of the Babe Ruth Award, given to the player with the best performance in the postseason. He hit .308 overall with 14 RBI, including a .391 batting average in the World Series.

But despite the World Series title, Fielder did not have a smooth offseason. He criticized Yankees manager Joe Torre for benching him in Game 1 of the ALDS vs. Texas and then asked the Yankees to trade him.

“I don’t understand Cecil,” Yankees teammate Darryl Strawberry told the New York Daily News. “Going from last to first, what’s not to like about that?”

Fielder held out of camp before finally reporting in mid-March and rescinding his trade demand. He had wanted a contract extension from the Yankees, but no offer was forthcoming.

“Basically, the reason I demanded a trade was to be traded,” Fielder told USA Today. “I was hoping something positive would come out of this whole ordeal, but it didn’t. Personally, I’ve got a job to do for the New York Yankees this year, and then I’ll take my chances.”

Fielder was the Yankees primary DH in 1997 but appeared in just 98 games due to a thumb injury, batting .260 with 13 homers and 61 RBI. He was booed by Yankee fans on Opening Day.

He went 1-for-8 in two games in the Yankees’ five-game loss to Cleveland in the ALDS, becoming a free agent when his contract expired at the end of the year.

On Dec. 19, 1997, Fielder returned to his Southern California roots by signing a one-year deal with the Angels worth $2.8 million. But before signing, he had contemplated retirement.

“Everyone comes to a point in their career where they wonder if this is what they really want to do,” Fielder told the Los Angeles Times. “But you don’t realize how much you miss the game until the first time you’re home watching it. I made up my mind I wanted to play.”

But the good vibes did not last. Despite recording 29 RBI in June alone and sharing the club lead (with Darin Erstad) in the category with 68, Fielder was released on Aug. 10.

“Anytime you make a decision to move one of the great players in the game, it’s not easy,” Angels manager Terry Collins told the AP. “We just decided to move in another direction. I really believe he’s going to be signed soon.”

Collins proved correct when Cleveland – who was without first baseman Jim Thome due to a broken hand – signed Fielder on Aug. 13. Fielder had long been Cleveland’s nemesis, having hit 30 career home runs in 109 games vs. the Indians. But after going 5-for-35 (.143) with no homers or RBI in 14 games, Fielder was released by Cleveland on Sept. 18.

It would mark the final pro games of Fielder’s career.

Fielder went to Spring Training in 1999 on a minor league deal with the Blue Jays – he led Toronto with three home runs in exhibition play – but was released on March 31 after the team traded for Dave Hollins. He soon announced his retirement.

Financial problems quickly caught up with Fielder, who reportedly lost hundreds of thousands of dollars gambling. He lost his 50-room mansion in Melbourne, Fla., and became alienated from family.

“I never saw any of this coming,” his longtime wife, Stacey Fielder, told the Detroit Free Press in 2004. “I never even knew he gambled.”

By then, Fielder’s son – Prince – was well on his way to becoming a big leaguer. He had been drafted by the Brewers with the seventh overall pick in the 2002 MLB Draft and hit minor league pitching just like his father did before debuting with Milwaukee in 2005.

“This is awesome. As a father, I couldn’t ask for anything better,” Fielder told the AP when Prince was selected by the Brewers. “Any parent wants to see their child do better than they did, and I’m convinced he’s going to be a better ballplayer than I ever was.”

By 2007, Prince was an All-Star with a NL-leading 50 home runs. Cecil and Prince Fielder remain the only father-son combination in MLB history with 50-home run seasons. And the family had a third generation in pro ball when Prince’s son, Jadyn Fielder, signed with the Brewers organization in 2024.

Cecil Fielder and his son eventually reconciled, and Prince retired from baseball due to a neck injury after 12 seasons. Both Cecil and Prince finished their big league careers with exactly 319 home runs.

For Cecil, his final MLB stat line included a .255 batting average, 1,313 hits, 200 doubles and 1,008 RBI. It was a remarkable resume for a player whose career path to stardom was anything but typical – but whose star burned brighter than almost any other MLB player in the 1990s.

“I always felt I could play, and my ex-team, the Blue Jays, always felt I could play,” Fielder told the AP during the 1990 season. “They just said there wasn’t room for me there, and I was happy when they let me go to Japan.

“When I was in Toronto, I didn’t face right-handed pitching, and I played only a couple times a week. That’s the toughest thing for any young player to do. I got an opportunity to play in Japan. I gained some confidence.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum