- Home

- Our Stories

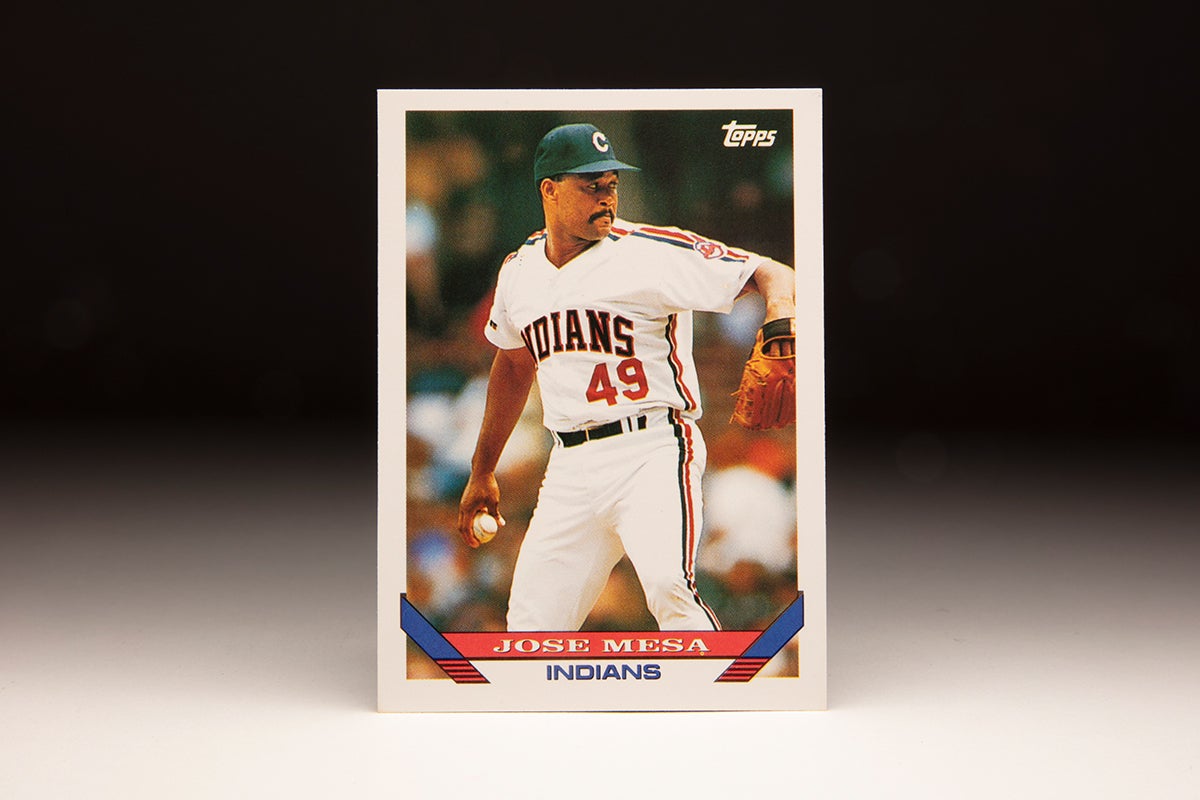

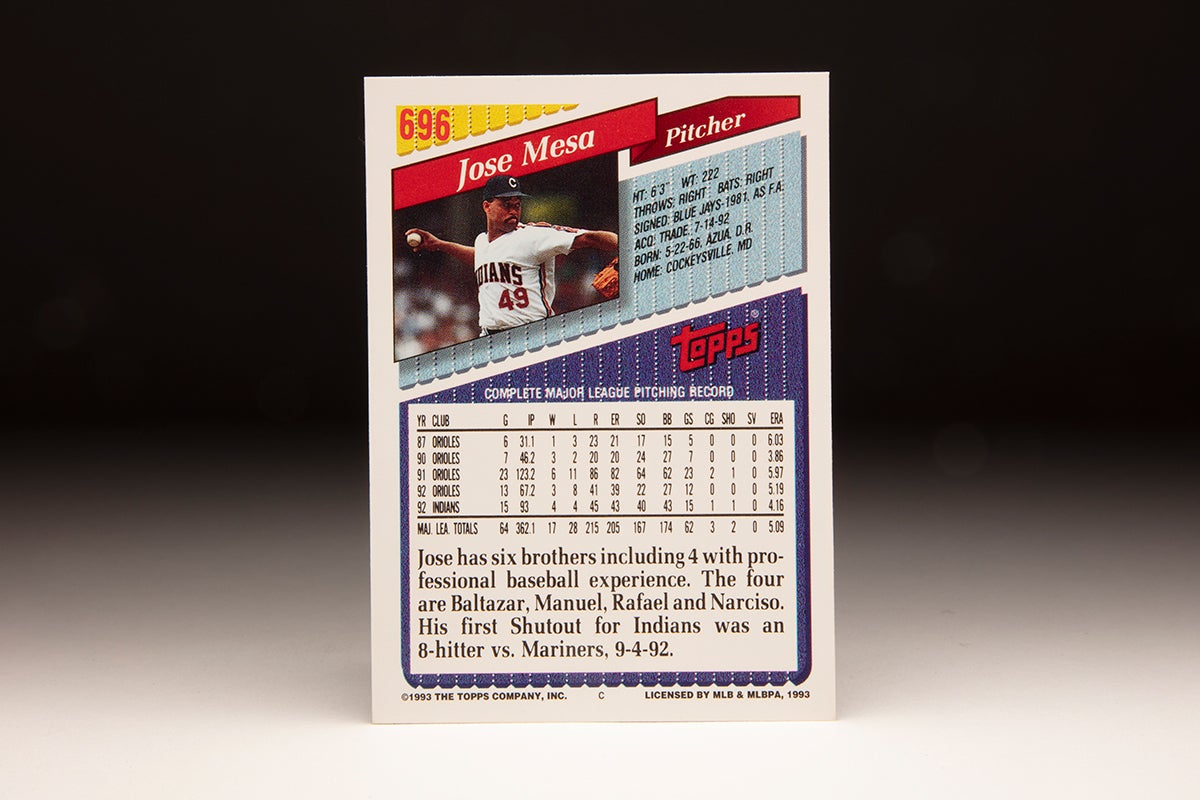

- #CardCorner: 1993 Topps José Mesa

#CardCorner: 1993 Topps José Mesa

It would be inaccurate – unfair, really – to call any pitcher with at least 300 career saves a “one-season wonder.”

And yet, José Mesa qualifies. For though he was an excellent reliever for much of his 19-year big league career, Mesa would never come close to repeating the otherworldly numbers he posted in 1995. Nor would almost any other reliever in baseball history.

Born May 22, 1966, in Pueblo Viejo, Dominican Republic, Mesa was the 12th of 15 children in a family headed by his father, Narciso, and mother, Maria. Narciso was a farmer, and José began working on the farm at an early age.

His father did not want him to play baseball, fearing that an injury would prevent him from working.

“Anytime he found me playing baseball, I’ve got to run or he’ll grab whatever he can grab and whip me with it,” Mesa told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 1999. “I was scared.”

But when Mesa was nine years old, his father suffered a stroke and died. This forced Mesa to work to support his three younger brothers – but also opened the door to a baseball career.

“It was a hard thing that he died,” Mesa told the Post-Intelligencer. “But I guess God wanted him to die, because he wanted me to play baseball.”

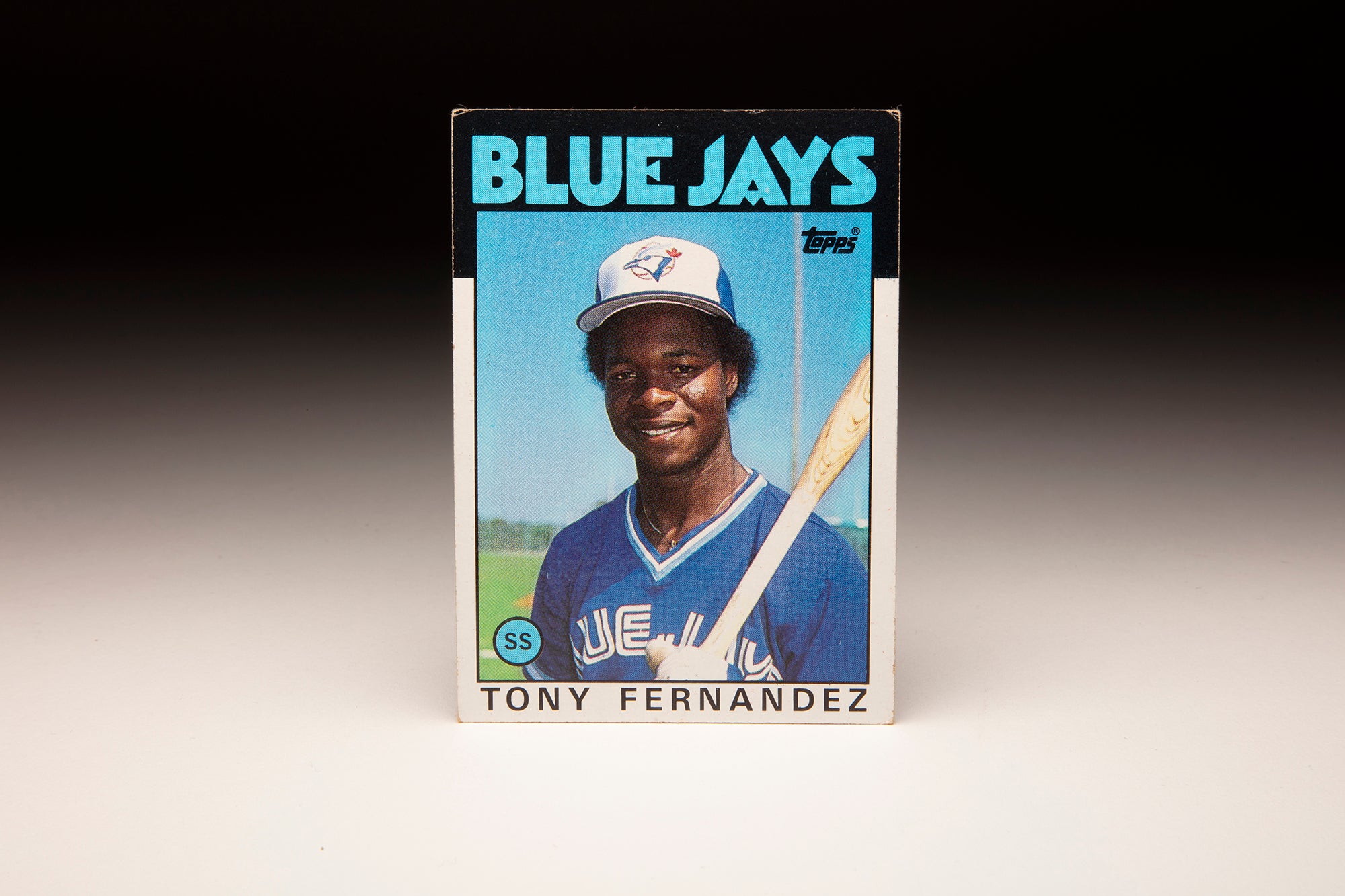

When Mesa was 15, he was summoned to a tryout with legendary scout Epy Guerrero, who was working for the Blue Jays. Impressed by Mesa’s arm, Guerrero signed him to a contract with a reported bonus of $3,000 on Oct. 31, 1981.

The Blue Jays assigned the 16-year-old Mesa to their Gulf Coast League team in 1982, and Mesa went 6-4 with a 2.70 ERA over 83.1 innings. He moved steadily up the organizational chain over the next few seasons, displaying a crackling fastball but also annually walking nearly as many batters as he struck out.

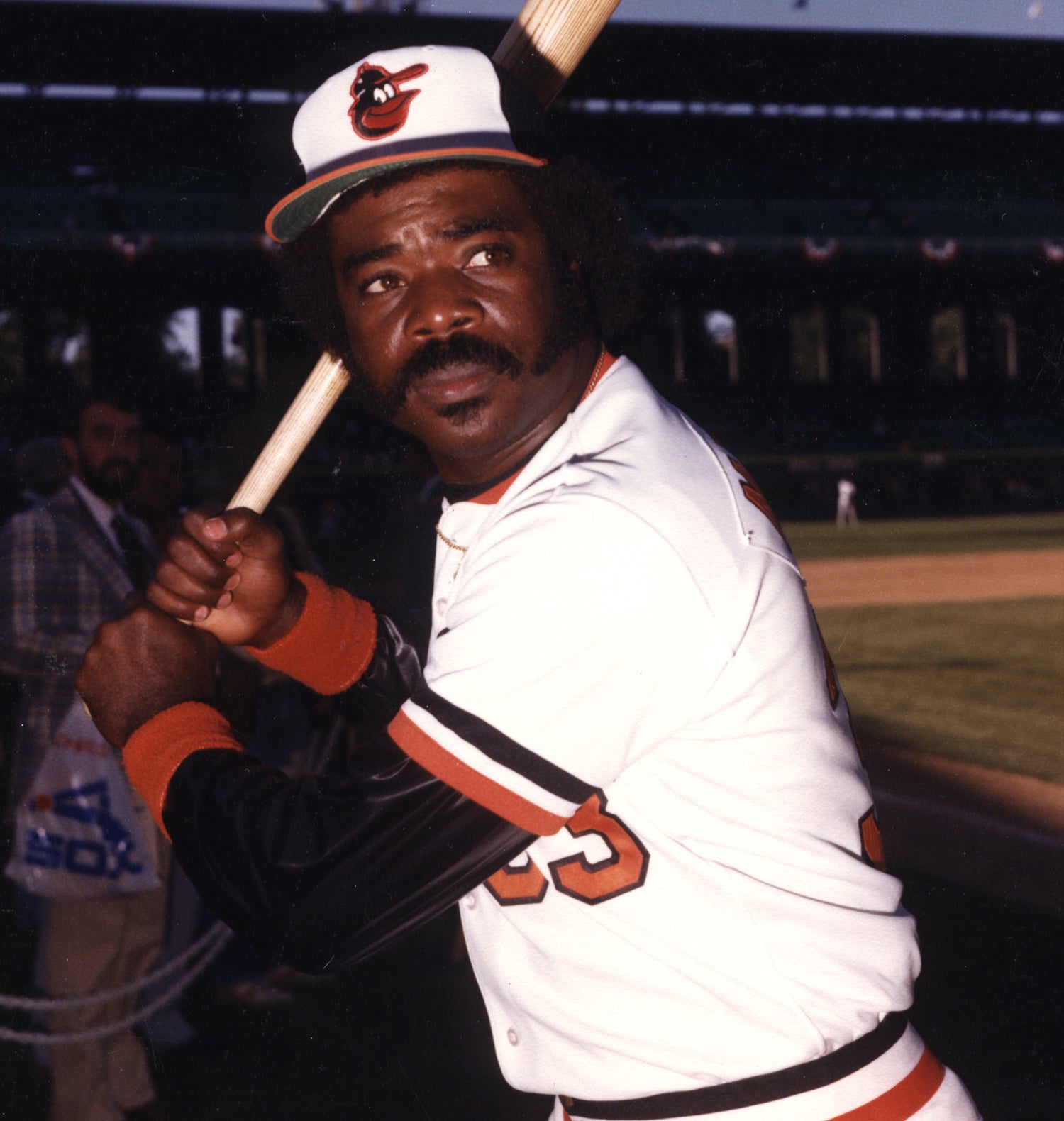

Reaching Double-A Knoxville at the end of the 1986 season, Mesa fanned 143 batters in 183.2 innings between Class A and Double-A that year. He pitched most of the 1987 season with Knoxville, going 10-13 with a 5.21 ERA over 35 starts. Then on Sept. 4, the Blue Jays sent Mesa to the Orioles as a player-to-be-named later in a deal that brought Mike Flanagan to Toronto.

The Orioles, at the tail end of a season that saw them lose 95 games, were anxious to see what Mesa had and immediately brought him to the big leagues. He debuted on Sept. 10, allowing three runs over six innings in a no-decision against the Red Sox. Mesa then lost three straight before picking up his first win on Sept. 30 against the Tigers, working 8.2 innings in a 7-3 win that left Detroit 1.5 games behind the first-place Blue Jays in the AL East.

“I want Toronto to win the pennant,” Mesa told the Associated Press after the win. “All my friends are still there.”

It would be the last regular season loss for Detroit that season as the Tigers would sweep a weekend series from Toronto to capture the division title.

Mesa, meanwhile, pitched in relief in Baltimore’s final game of the season on Oct. 4, working three scoreless innings in a win over the Yankees. He finished his six-game stint with Baltimore with a 1-3 record and 6.03 ERA.

It would be three years before Mesa would return to the major leagues.

In 1988, the Orioles made Mesa a reliever and sent him to Triple-A. But he soon needed Tommy John surgery to rebuild his right elbow and pitched in only 11 games that year followed by 10 more in 1989. In 1990, Mesa started the year at Double-A Hagerstown and was again a starter before heading back to Triple-A Rochester, going a combined 6-7 with a 3.17 ERA. The Orioles then brought him back to Baltimore late in the season, where he was 3-2 in seven starts.

“I think (the surgery) gave me two or three extra miles per hour,” Mesa told the Baltimore Sun. “Why not? I have a new ligament in there. It’s stronger.”

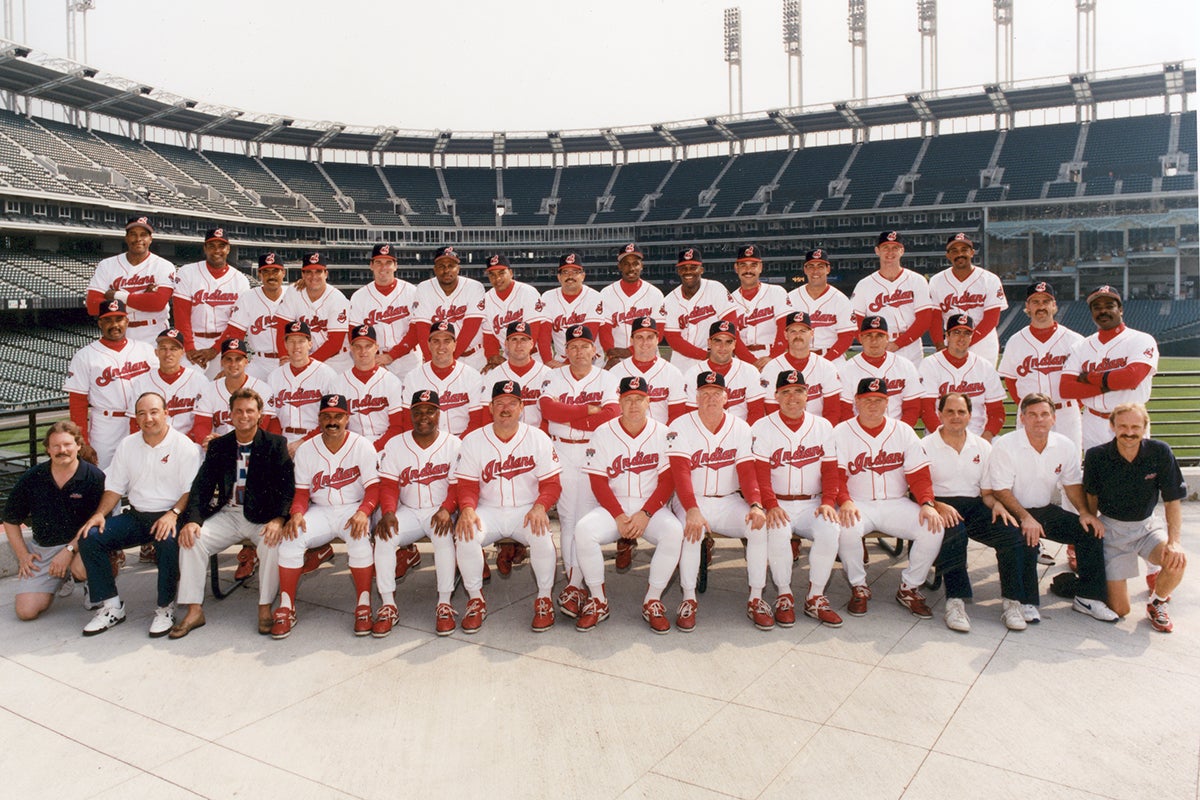

In 1991, Mesa made 23 starts for the Orioles, going 6-11 with a 5.97 ERA. He was 3-8 with a 5.19 ERA in 13 appearances in 1992 before his career path changed for good when the Indians acquired him from the Orioles on July 14 in exchange for minor leaguer Kyle Washington. Cleveland kept Mesa as a starter for the rest of the season, and he finished with a 7-12 record and 4.59 ERA in 160.2 innings.

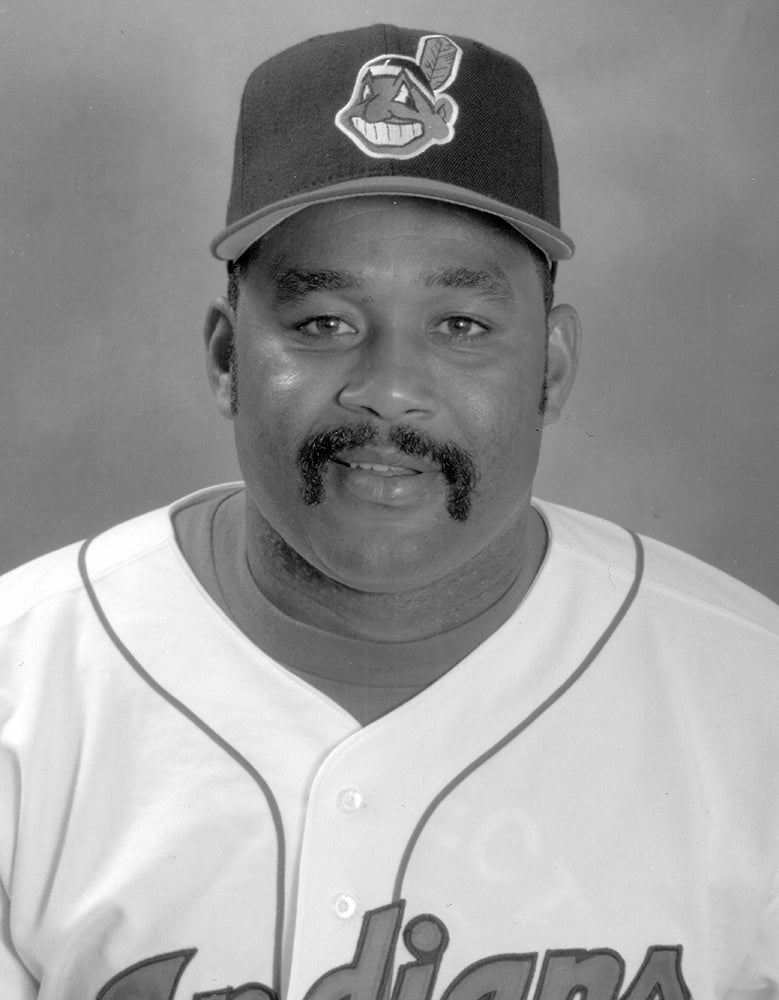

In 1993, Mesa was still a starter and posted a 10-12 record with a 4.92 ERA in 208.2 innings. He was the only Cleveland pitcher to reach double-digits in wins. But heading into the 1994 season, the Indians moved Mesa to the bullpen – a decision Mesa did not appreciate.

“We made him a set-up man with the idea in mind that he might become a closer,” Cleveland general manager John Hart told the Sun. “He’s a two-pitch guy. A power guy. We weren’t writing him off, but we felt that he might be limited as a starter.”

Mesa adapted quickly to his new role as the Indians’ young roster jelled. Mesa went 7-5 with two saves and a 3.82 ERA in the strike-shortened 1994 season, appearing in 51 games as Cleveland went 66-47. But no Indians pitcher had more than five saves that year, and rumors abounded that the team would be looking for a veteran closer as soon as the labor stoppage ended.

“When we did his (new) contract, he asked me ‘Am I going to get that shot?’” Hart told the Sun during the 1995 season. “We said ‘We’re not going to get anybody else.’”

Hart’s decision turned out to be one that would help bring Cleveland its first AL pennant since 1954. Mesa picked up a win in the team’s fourth game of the year on April 30, got a save five nights later and notched saves in 14 straight appearances from May 20-June 17. He had 21 saves at the All-Star break, 29 at the end of July and did not blow his first save opportunity until Aug. 25.

He would finish the season 3-0 with a 1.13 ERA in 62 games, with 46 saves in 48 opportunities. Cleveland won 60 of the 62 games in which Mesa pitched.

“I never thought,” Mesa told the Sun, “I’d be leading the league in saves and in the same company with guys like Dennis Eckersley and Lee Smith.”

Cleveland went 100-44 in 1995 and won the AL Central by 30 games over the runner-up Kansas City Royals. Mesa pitched two scoreless innings in the Indians’ sweep of the Red Sox in the ALDS and picked up a save in the ALCS vs. Seattle as Cleveland advanced to the World Series for the first time in 41 years. Mesa got the win in Game 3 of the World Series vs. the Braves, working three scoreless innings before Eddie Murray won the game with a walk-off single in the bottom of the 11th inning. But the Braves still led the series 2-games-to-1 at that point and won Game 4 to take a commanding lead. Mesa saved Cleveland’s 5-4 win in Game 5 but the Indians were shut out by Tom Glavine and Mark Wohlers in Game 6, ending their magical season.

Mesa finished second in the AL Cy Young Award voting behind Randy Johnson and fourth in the AL MVP voting – and was now firmly entrenched as one of the game’s top closers.

With virtually the whole roster returning in 1996 and the addition of Jack McDowell to the rotation, the Indians were heavy favorites to return to the World Series. Mesa recorded 39 saves but was not as untouchable as he was in 1995, going 2-7 with a 3.73 ERA in 69 games. But Cleveland repeated as AL Central champions and seemed poised for a deep postseason run after finishing second in the league in runs scored (952) and first in ERA (4.34).

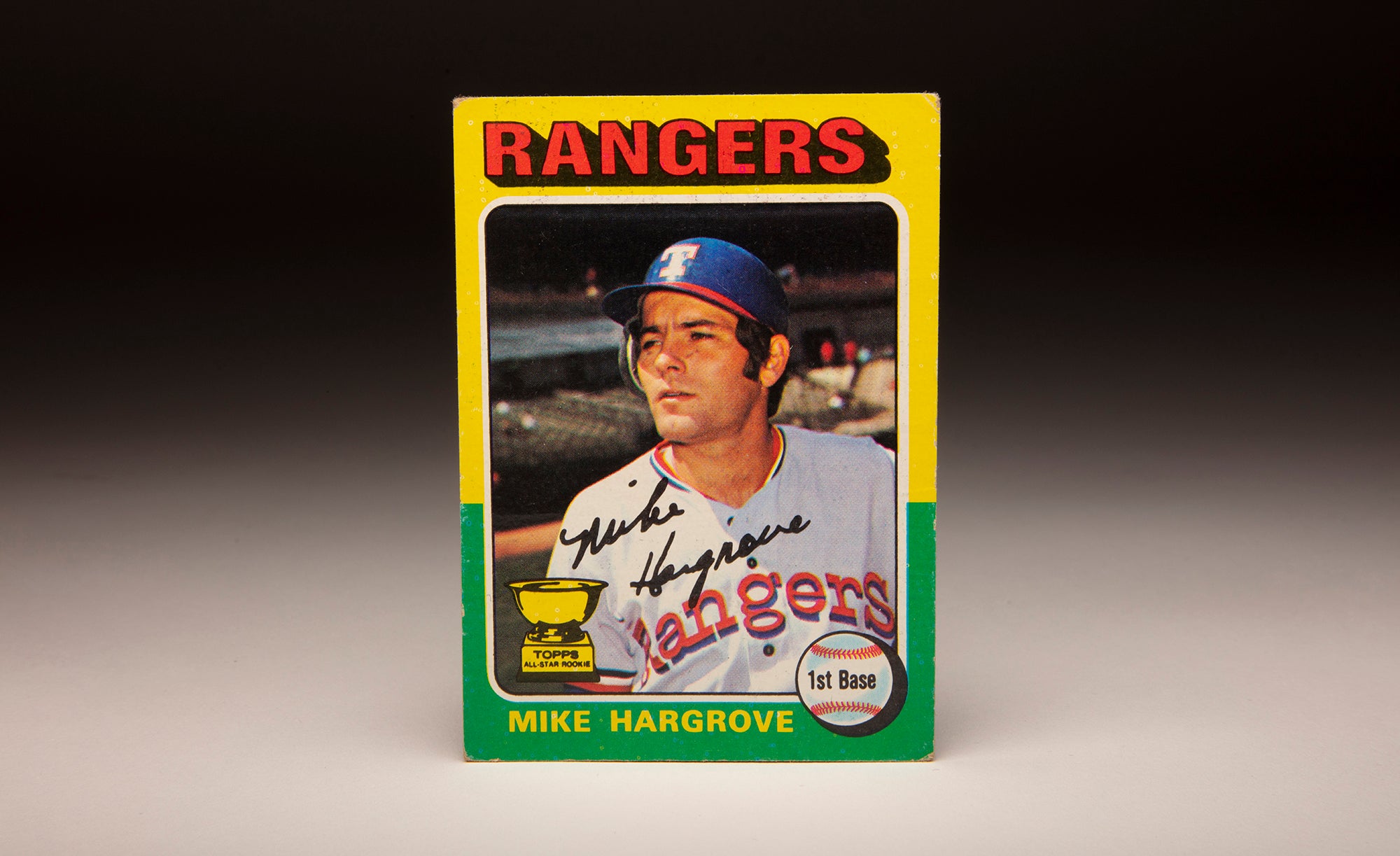

But in the ALDS vs. the Orioles, Cleveland lost the first two games to put its season on the brink. The Indians won Game 3 by a 9-4 score – and manager Mike Hargrove used Mesa in the ninth inning to get him some work. But the next day, Game 4 proved to be much closer as Cleveland led 3-2 heading into the top of the ninth. Hargrove again called on Mesa, but this time Baltimore rallied to tie the game on Roberto Alomar’s two-out single that scored Manny Alexander.

Having used all his high-leverage relievers to get to the ninth, Hargrove kept Mesa on the mound in the 10th and 11th as neither team scored. But in the 12th, Alomar led off with a home run – and Baltimore closer Randy Myers shut the door in the bottom of the inning to knock Cleveland out of the postseason.

It was Mesa’s longest outing since Aug. 7, 1994, when he was Cleveland’s set-up man.

“Jose Mesa has been good for us all year,” Hargrove told Thomson News Service after Game 4. “The inning before he went back out for that last time, he was outstanding. Overpowering.”

But the toughest times for Mesa in 1996 were yet to come. On Dec. 22, he was arrested and charged with gross sexual imposition and possessing a concealed weapon. Facing decades in prison, Mesa went to trial just before the 1997 season opened. A jury acquitted him of all charges.

“I’ve changed a lot of things, off the field and everywhere,” Mesa told the Post-Intelligencer in 1999. “You’ve got to change from that situation…You’ve got to think about it and think about your family.”

Mesa’s numbers in 1997 looked fine – a 4-4 record with 16 saves and a 2.40 ERA in 66 games – but Hargrove often turned to Michael Jackson in save situations. But in the postseason – Cleveland won the AL Central crown with a record of 86-75 – Hargrove used Mesa as his closer, and Mesa saved Game 5 of the ALDS vs. the Yankees to send Cleveland to another matchup with the Orioles in the ALCS.

Mesa pitched in Games 2, 3 and 4 – all Cleveland wins – picking up a victory and a save. Then in Game 6, Charles Nagy and Mike Mussina matched zeroes before the bullpens took over. Cleveland broke the ice in the top of the 11th on a home run by Tony Fernández, and Mesa entered the game in the bottom of the inning to close the door. He allowed a two-out single to Brady Anderson but struck out Alomar – who had beaten him in the postseason the year before – to end the game and send Cleveland to the World Series.

In the Fall Classic against the Marlins, Mesa pitched in five games – earning a save in Game 6 as Cleveland pushed the series to the limit. Then in Game 7, Cleveland led 2-1 going into the bottom of the eighth, and Hargrove used Jackson to get the first two outs before turning to left-hander Brian Anderson for a matchup with lefty batter Darren Daulton. Marlins manager Jim Leyland countered with pinch-hitter Jeff Conine, who flew out to left field to end the inning. But the moves left Hargrove with only one trusted reliever – Mesa – entering the ninth.

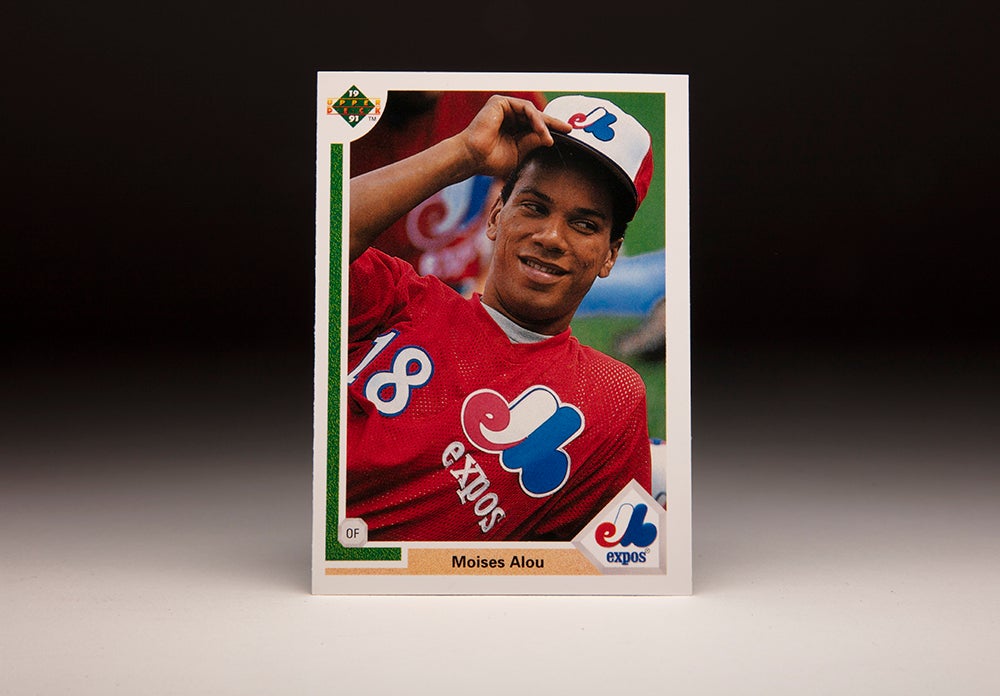

With the World Series on the line, Mesa allowed a leadoff single to Moisés Alou before striking out Bobby Bonilla. But Charles Johnson singled Alou to third, and Alou scored to tie the game on Craig Counsell’s sacrifice fly.

The game advanced to extra innings, and Mesa was lifted in favor of Nagy with two on and two out in the 10th and Alou at the plate. Nagy got Alou to fly out to push the game to the 11th inning, but after Cleveland failed to score the Marlins won the title on Édgar Rentería’s walk-off single.

It was Mesa, however, who bore the brunt of much of the postgame criticism.

“Unless you’re down on the field with a uniform on, you can’t understand how it feels,” Cleveland shortstop Omar Vizquel told the Denver Post. “Those were the longest minutes of my life.”

Five years later, Vizquel would tell the world just how he felt that day – and how he felt about Mesa’s performance.

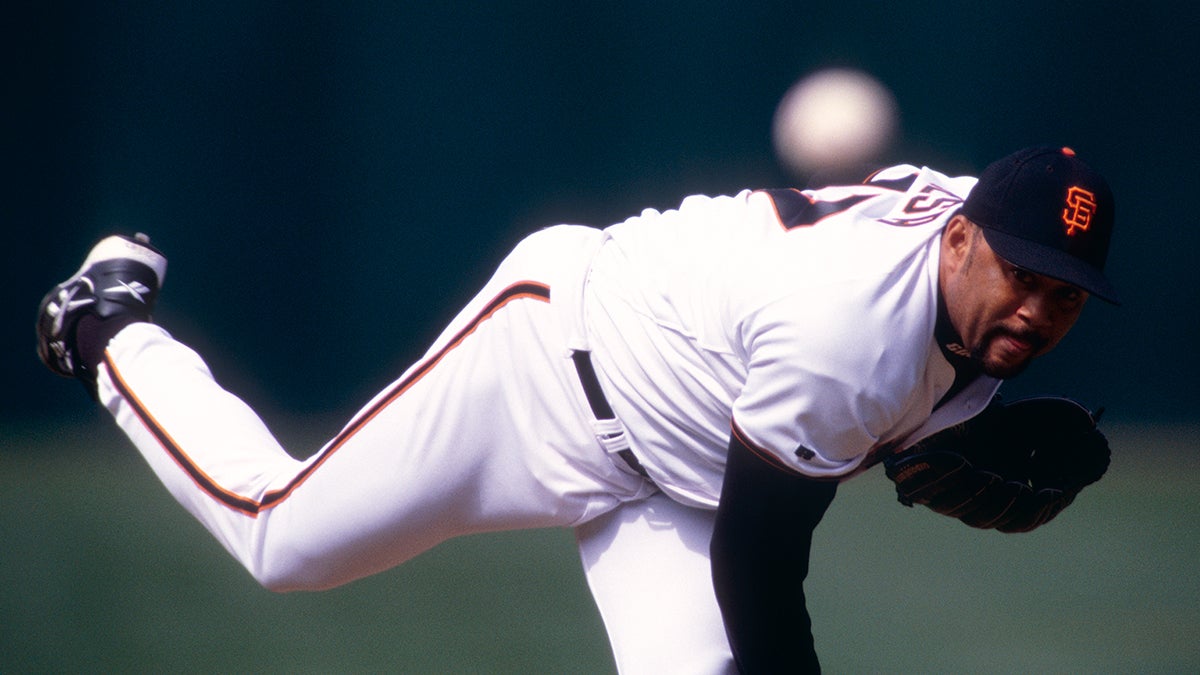

Mesa struggled in 1998 and was moved out of the closer’s role in favor of Jackson. Mesa was 3-4 with a 5.17 ERA in 44 games when Cleveland traded him with Shawon Dunston and Alvin Morman to the Giants on July 23 in exchange for Jacob Cruz and Steve Reed. Mesa pitched much better in San Francisco, going 5-3 with a 3.52 ERA in 32 games.

With his contract expiring, Mesa became a free agent and signed a two-year deal with the Mariners – worth a reported $6.8 million.

“Mesa will be our closer next season,” Mariners manager Lou Piniella told the Associated Press when the deal was announced. “He has a proven record of success.”

Mesa saved 33 games for Seattle in 1999 but had a 4.98 ERA. The next season, the Mariners signed Kazuhiro Sasaki to be their closer – and Mesa was 4-6 with a 5.36 ERA in 66 games in a set-up role. He posted a win in Game 1 of the Mariners’ sweep of the White Sox in the ALDS but allowed six earned runs over 4.1 innings in Seattle’s loss to the Yankees in the ALCS.

Entering his age-35 season, Mesa signed with the Phillies and had a career rebirth, going 3-3 with 42 saves and a 2.34 ERA in 71 games. He saved 45 more games in 2002 – the same season Mesa found himself the target of criticism by former Cleveland teammate Omar Vizquel, who wrote in a book that Mesa’s eyes were “vacant” when he went to the mound in Game 7 of the 1997 World Series.

“If I face him, I’ll hit him,” Mesa told the Bucks County (Pa.) Courier Times in the spring of 2003 when the Phillies were preparing to face Cleveland in an exhibition game. “I won’t try to hit him in the head, but I’ll hit him. If I face him 10 more times, I’ll hit him 10 times. Every time.”

Mesa would hit Vizquel with pitches multiple times over the next few seasons.

Mesa posted a 6.52 ERA with 24 saves in 2003 before his contract expired and he signed with Pittsburgh. Once again, Mesa proved he was not finished – going 5-2 with a 3.25 ERA and 43 saves in 70 games. He saved 27 more games for the Pirates in 2005, including the 300th of his career on April 27 in a 2-0 Pittsburgh win over the Astros. He became the 19th pitcher in history to record 300 saves.

“When you think about the history of the game and how many people have achieved what he just did, it’s amazing,” Pirates bullpen coach Bruce Tanner told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “His name should be talked about with all the great relievers.”

Mesa hooked on with Colorado in 2006, where he made a career single-season high 79 appearances while going 1-5 with a 3.86 ERA in a set-up role. He split his last big league season with the Tigers and the Phillies, helping Philadelphia win the NL East and pitching one game in the NLDS vs. the Rockies, who swept Philly out of the postseason. When Mesa found no suitable offers for the 2008 season, he retired.

He finished his 19-year big league career with an 80-109 record and 4.36 ERA while totaling 321 saves and made 1,022 appearances, a games pitched total that ranks 12th on the all-time list.

His peak may have been a short one, but few relievers ever dominated like José Mesa did in 1995 – just one year after he saw his move to the bullpen as a demotion.

“I was really upset,” Mesa told the Baltimore Sun. “I was coming off my best year (in 1993). The next thing you know, you’re a reliever. I was mad.

“Now I just say: ‘Thank God’ the Orioles traded me.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum