- Home

- Our Stories

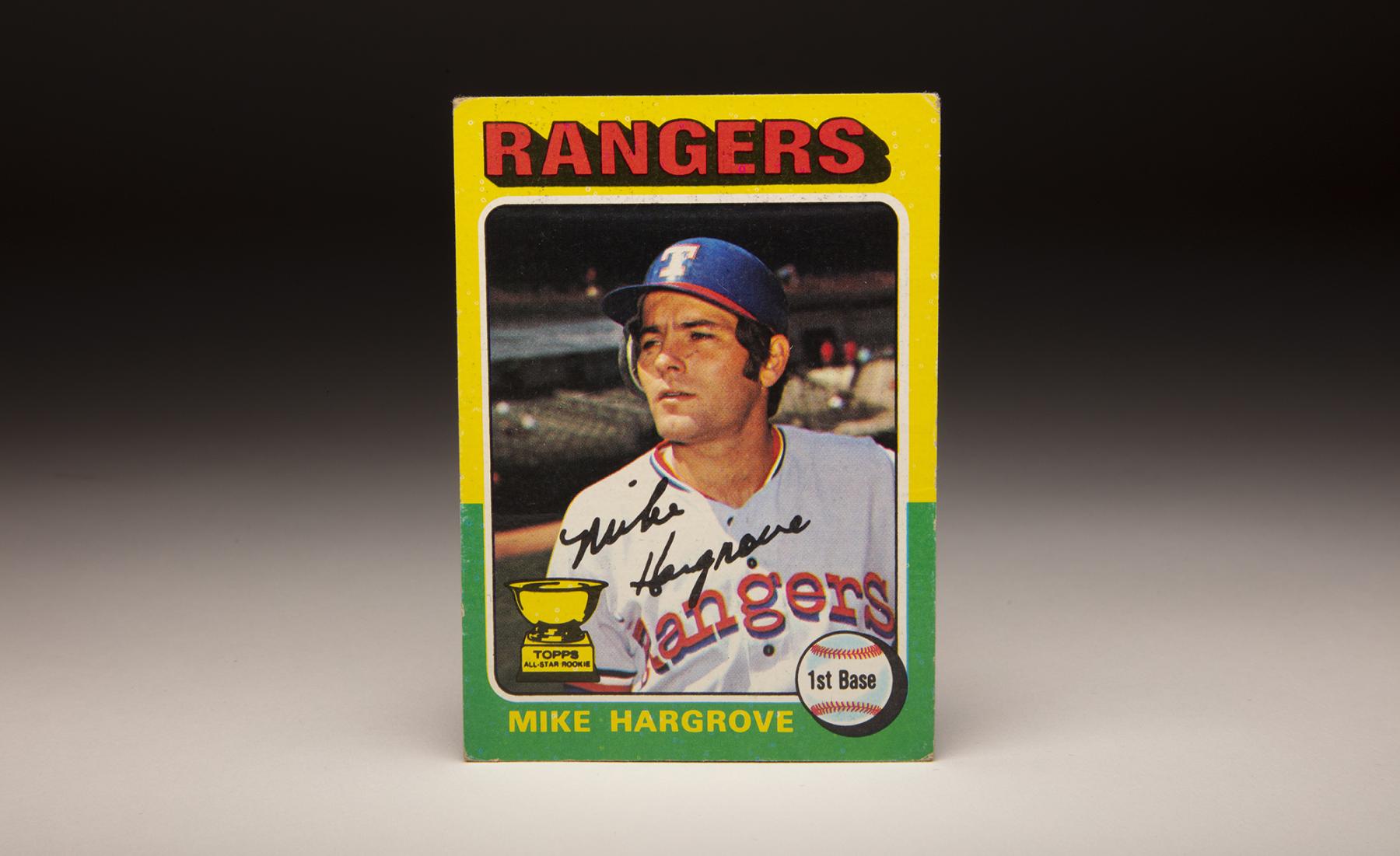

- #CardCorner: 1975 Topps Mike Hargrove

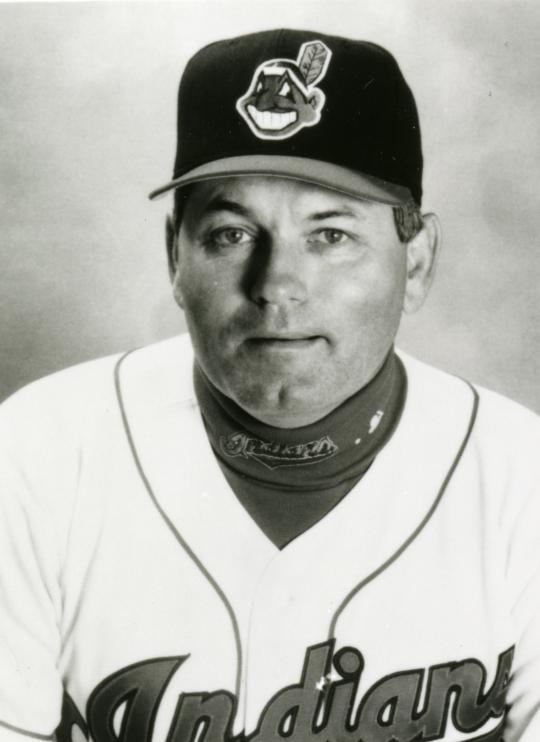

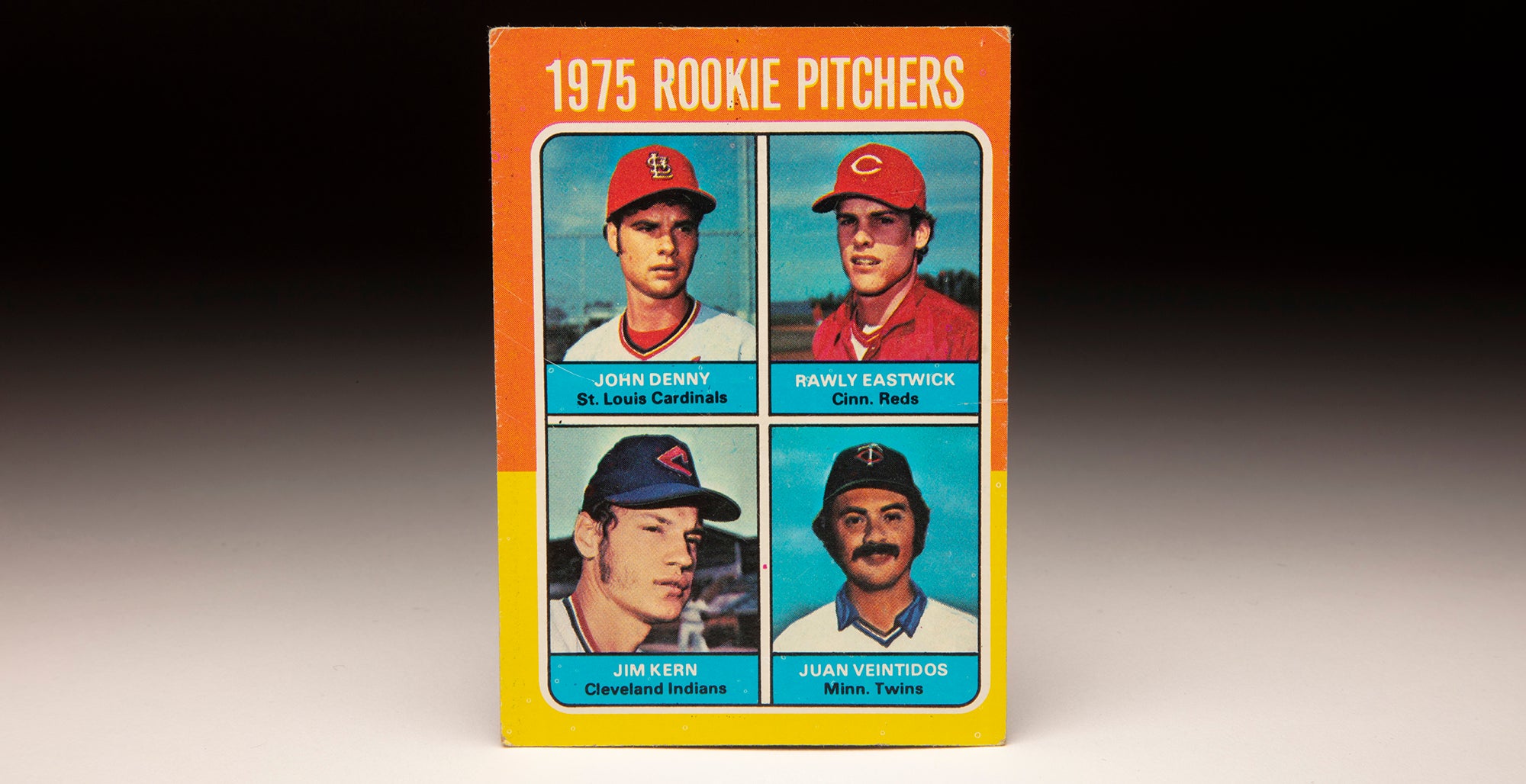

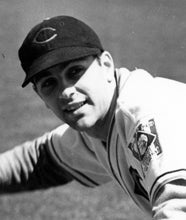

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Mike Hargrove

He would have been a statistical darling of today’s on-base percentage set, but played in an era where walks were undervalued.

He managed one of the most dominant teams of the 1990s, but a few bad bounces denied him the chance to skipper a World Series winner.

And he had the best nickname – The Human Rain Delay – of his time.

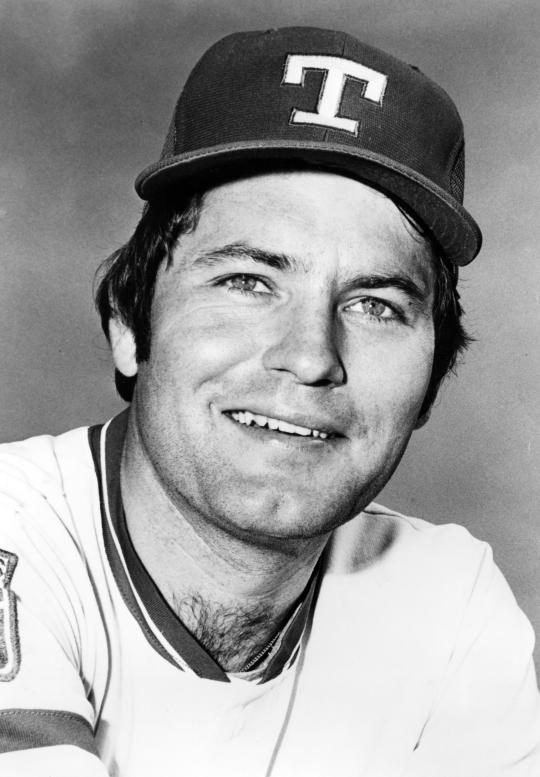

Mike Hargrove left his fingerprints all over baseball history. And few had more passion for the game.

Born Dudley Michael Hargrove in Perryton, Texas, on Oct. 26, 1949, the man who would become a baseball lifer could not play high school baseball because his school did not field a team. But Hargrove was an exceptional all-around athlete and earned a basketball scholarship to Northwestern Oklahoma State University.

“I asked my coach why we didn’t play baseball at school and he said it was too cold,” Hargrove told the Associated Press in 1974. “I considered going to (Texas Christian University) on a football scholarship after high school. If I had done that, I would probably be out coaching somewhere now.”

Hargrove played Little League and American Legion ball before college – and his father convinced him to give baseball a try at Northwestern Oklahoma State. He played one year of football and two seasons of basketball for the Alva, Okla., based school, but his four-year baseball career earned him a look from the Rangers, who selected him in the 25th round of the 1972 MLB Draft.

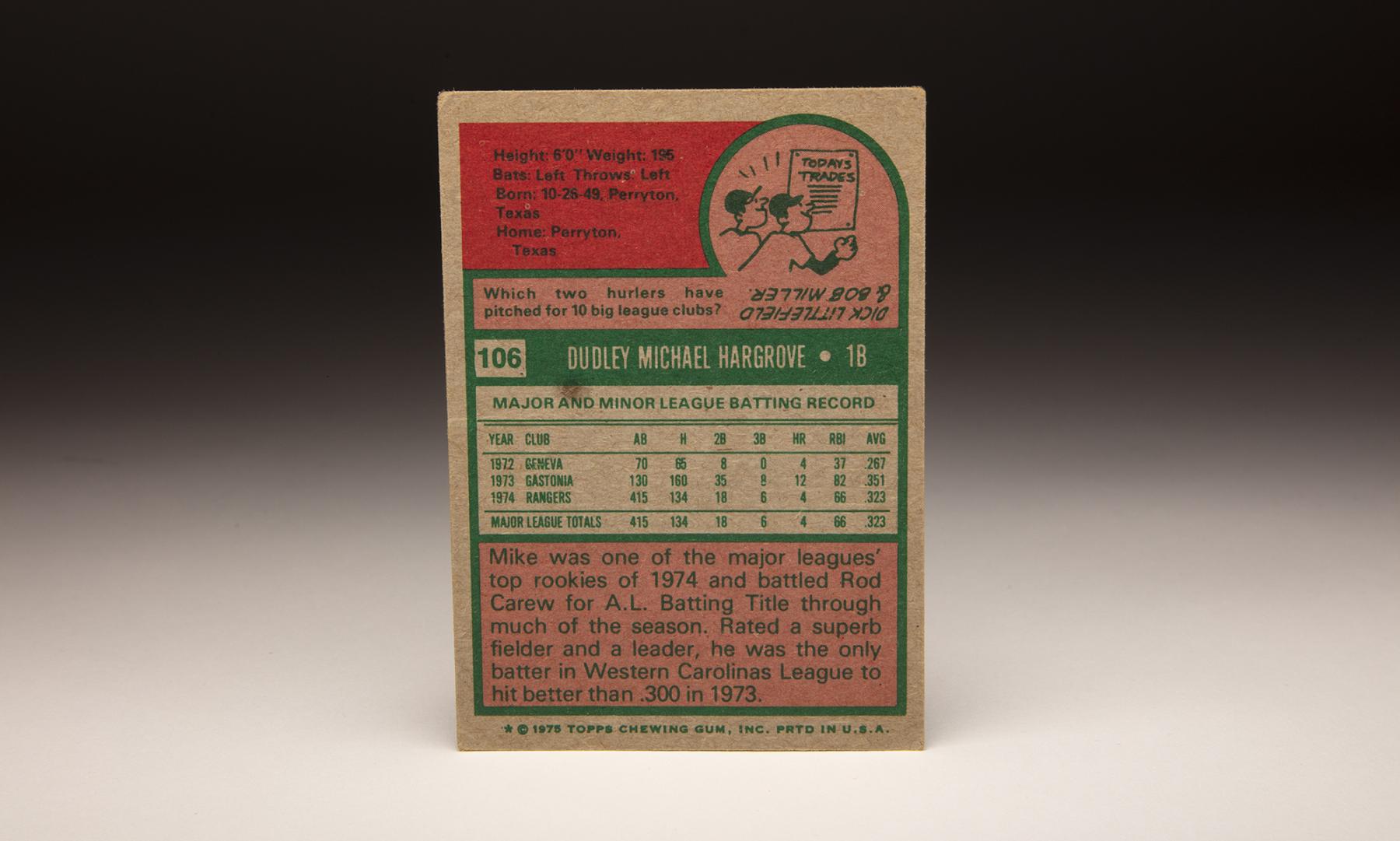

The lefty-swinging Hargrove was sent to Geneva of the New York-Penn League, where he hit .267 with a .396 on-base percentage in 70 games. The next season at Gastonia of the Western Carolinas League, Hargrove hit .351 with a .437 on-base percentage but was seen by many as too old (at 23) for that league.

“I am never going to make it,” Hargrove recalled telling his wife Sharon after a day of work in the Texas panhandle oil fields following his 1973 season. “I am already 23 years old, which is too old. I am coming off a good season in the Western Carolinas League, but my first season in the New York-Penn League was not very good at all.”

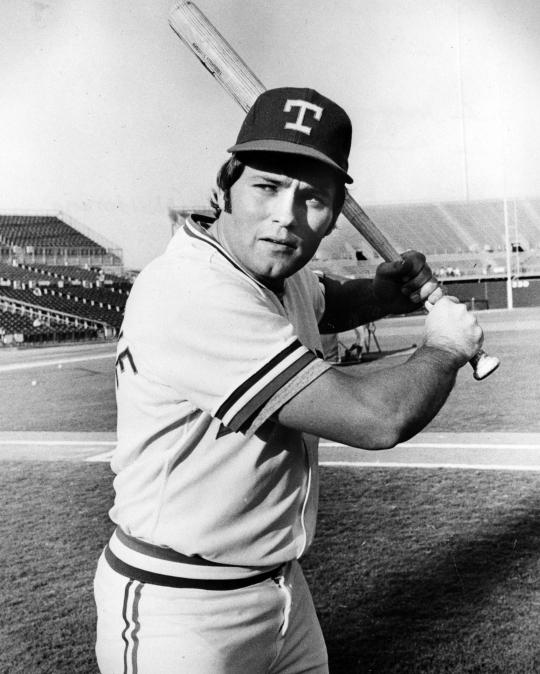

But the Rangers invited Hargrove to Spring Training in Pompano Beach, Fla., in 1974. He kept his average near the .500 mark the entire spring, impressing manager Billy Martin with his plate discipline and line drives.

Martin, who took over a Rangers team in late 1973 that would go 57-105 that season, was looking for players to provide a spark. Hargrove fit that mold.

“It’s an old phrase, but you could have knocked me over with a feather,” Hargrove told the Boston Globe, referring to when he learned that he had made the Rangers’ Opening Day roster. “I like died. I was just kind of floating. I called my wife (and) I don’t even know what I said.”

Hargrove let his bat do the talking for him in 1974 and moved into the regular lineup after starting first baseman Jim Spencer was injured. Often platooned by Martin so he would not have to face left-handers, Hargrove was hitting .344 as late as Sept. 1 before finishing at .323, which would have been good for second place in the AL behind Rod Carew had Hargrove amassed the 25 extra plate appearances he needed to qualify for the batting title.

He walked 49 times, drove in 66 runs and compiled a .395 on-base percentage – and was the runaway winner of the American League Rookie of the Year Award.

Hargrove also demonstrated his remarkable routine at the plate, which featured him stepping out of the batter’s box between every pitch to adjust his cap and gloves, hitch up his pants and tighten a thumb donut he used to protect the digit.

At the time, Hargrove was virtually the only player in baseball to take such a deliberate approach.

“He thrived on agitating pitchers,” former South Atlantic League president John Henry Moss told the Charlotte Observer in 1992 while reminiscing about former Gastonia Rangers stars like Hargrove. “Sometimes he took so long, I had to talk to my umpires about speeding him up.”

But Hargrove’s teammates and coaches loved him.

“Well, put it this way,” Texas coach Frank Lucchesi – who would go on to manage the Rangers from 1975-77 – told the Boston Globe in July of 1974. “The kid is the greatest find since the nickel beer.”

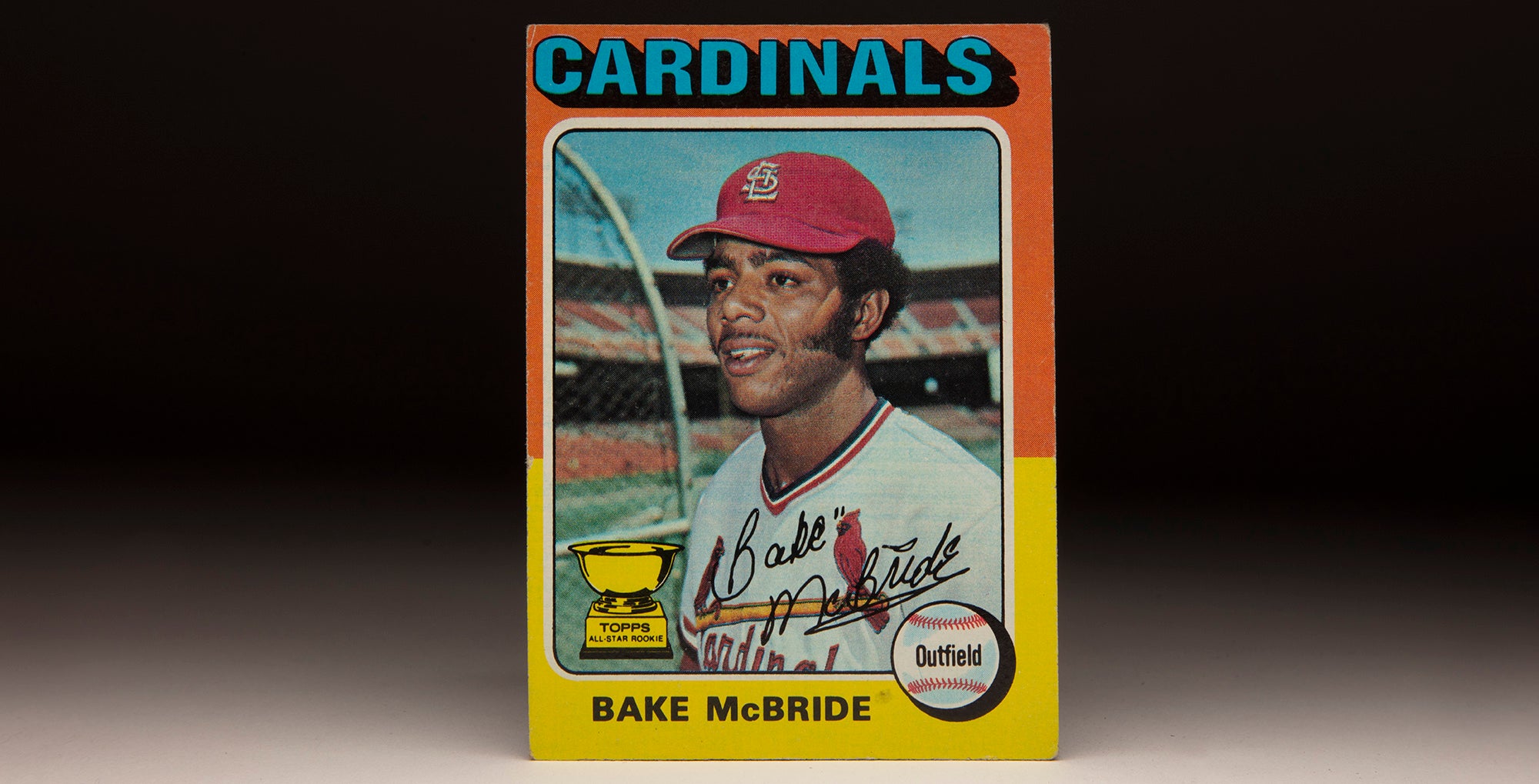

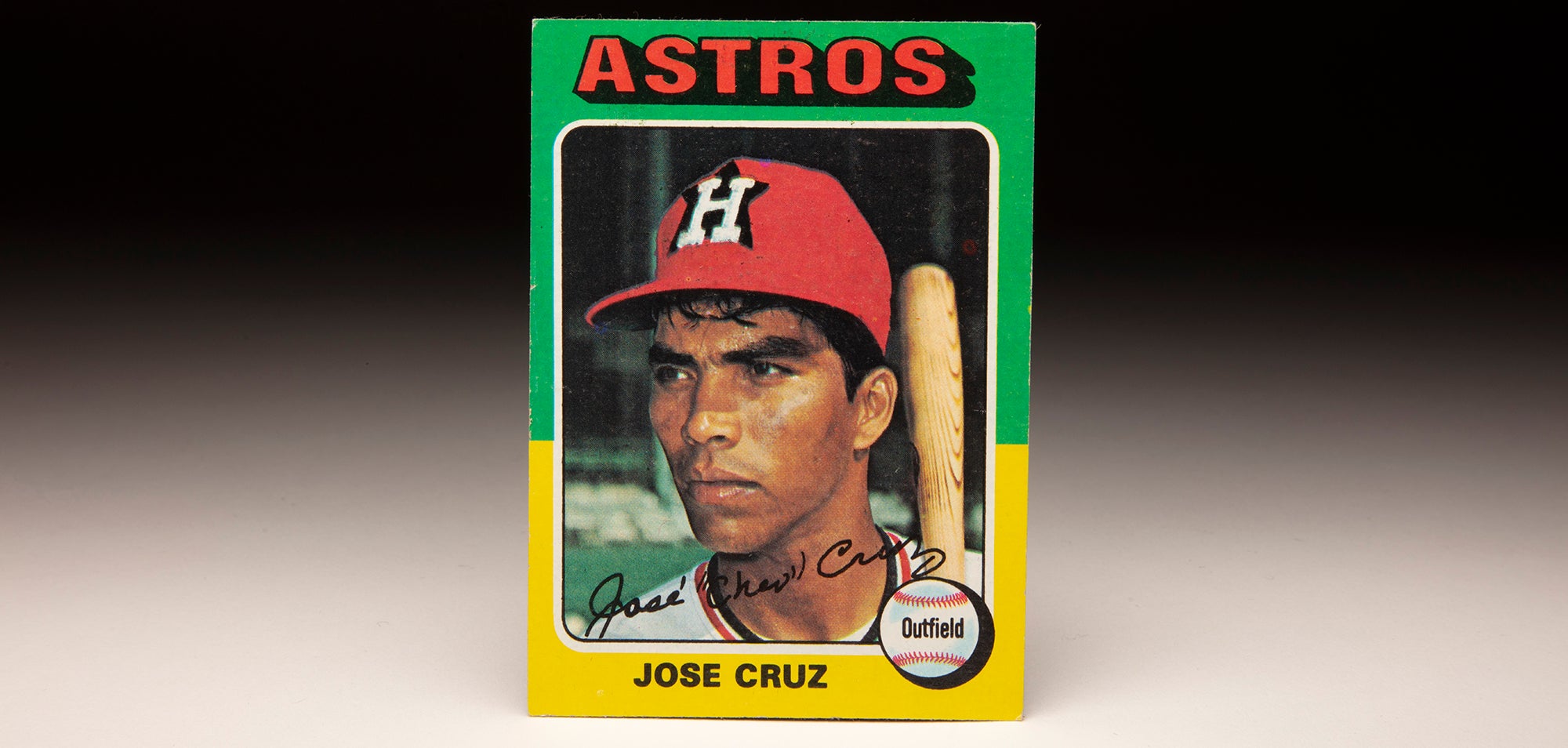

The Rangers moved Hargrove to left field early in the 1975 season to make room for Spencer, and Hargrove was rewarded with his first All-Star Game selection. He hit .305 with 11 homers, 82 runs scored, 66 RBI and a .395 on-base percentage. He was hitting .365 as late as mid-June and led the AL for several weeks before finishing 10th in the batting race as Carew won his fourth straight title with a .359 mark.

In 1976, Hargrove returned to first base and led the AL with 97 walks while hitting .287 with 80 runs scored, seven homers and 58 RBI. Then in 1977, the Rangers employed four different managers during a tumultuous season that saw them win 94 games. The fourth manager, Billy Hunter, made the unorthodox decision to move Hargrove to the top of the Rangers’ batting order – ignoring the conventional wisdom of the day that said that leadoff hitters must possess above-average footspeed.

In his first three seasons in the big leagues, Hargrove stole a total of six bases en route to 24 over his entire 12-year big league career.

In the season’s final 74 games, Hargrove batted .308 with a .440 on-base percentage to go with 16 homers, 40 RBI and 61 runs scored. He finished the season with a .305 batting average, 98 runs scored, 18 homers, 69 RBI and 103 walks.

“I had over 200 walks in the last two years and that’s the idea for a leadoff man: To get on base,” Hargrove told the Associated Press in Spring Training of 1978. “A walk isn’t what you’re looking for from the 3-4-5 guy.”

Hargrove hit out of the leadoff spot for most of the 1978 season and wound up leading the AL in walks with 107 while posting a .388 on-base percentage. But his batting average dropped to .251 to go with seven home runs and 40 RBI – hiding his value in an era where players were judged by batting average and counting statistics. Hargrove also led all AL first baseman in assists that season with 116, improving his defense vastly from the 1976 campaign where he led the league with 21 errors.

The Rangers finished a disappointing 87-75, a mark that was inflated by a 15-2 stretch to end the season when Texas was out of contention. On Oct. 25, 1978, the Rangers packaged Hargrove with Kurt Bevacqua and Bill Fahey in a deal that brought Oscar Gamble, Dave Roberts and $300,000 from San Diego.

Hargrove was not shy in denouncing his former team.

“They probably did a good thing to trade me to the other league,” Hargrove told the Associated Press. “If they hadn’t, I’d…have eaten first base if I had to (to) help beat Texas. I knew (the trade) would come someday, but I’m surprised and hurt it happened this soon.”

But in an era where hitters rarely faced pitchers from the rival league, Hargrove struggled in the NL. The Padres chose not to use Hargrove in the leadoff spot and he hit just .200 in the season’s first two months before being relegated to a pinch-hitting role.

On June 14, 1979, the Padres sent Hargrove to the Indians in a one-for-one deal for utility man Paul Dade. It was a trade that brought Cleveland a man who would one day lead the Indians to the top of the American League.

“In early June, I was talking with (Indians president) Gabe Paul about how we needed a left-handed hitter,” Jeff Torborg – who managed the Indians in 1979 – told the Akron Beacon-Journal 16 years later as Hargrove led the Indians into the 1995 World Series. “They wanted Paul Dade for Mike, but (Paul) said Dade was our catalyst.

“Paul said: ‘OK, we’ll do it. But if it doesn’t work out, it’s your butt.’”

Hargrove hit .325 with a .433 on-base percentage in 100 games for Cleveland, finishing the season with a combined total of 10 homers, 75 runs scored and 64 RBI to go with a .289 batting average and .404 on-base percentage.

Dade’s final big league season was 1980. That same year, Hargrove put together what was probably his best year in the big leagues, hitting .304 with 86 runs scored, 11 homers, 85 RBI, 111 walks and a .415 on-base percentage in 160 games.

He was on target for a similar season in 1981 when the strike wiped out nearly two months of play, but finished with a .317 batting average, 60 walks, 43 runs, 49 RBI and an AL-best .424 on-base percentage in 94 games.

Neither campaign earned Hargrove a berth in the All-Star Game due to the presence of heavy-hitting first basemen in the AL like Eddie Murray and Cecil Cooper. But Hargrove’s Offensive Wins Above Replacement of 7.2 for 1980-81 was better than every big league first baseman except for Murray, Cooper and Keith Hernandez.

Hargrove hit .271 with 101 walks and a .377 on-base percentage in 1982, then began slowing down as the Indians phased in younger players. He hit .286 with a .388 on-base mark in 134 games in 1983, then transitioned into more of a part-time role over the next two seasons while playing mostly against right-handed starters.

Becoming a free agent following the 1985 season, the soon-to-be 36-year-old Hargrove found few offers and accepted a non-roster invite to Spring Training with the Athletics in 1986.

“One of the things I’ve learned over the years is that everything comes down to one thing: Baseball is a business,” Hargrove told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram after he failed to catch on with Oakland. “You can’t take it as an affront every time a team doesn’t offer you a contract.”

Hargrove announced his retirement and quickly joined the Indians as a minor league instructor before being named manager of Cleveland’s Kinston outpost in the Class A Carolina League in 1987.

Hargrove led the team to a 75-65 record while earning manager of the year honors, then skippered Double-A Williamsport in 1988 and Triple-A Colorado Springs in 1989. After winning manager of the year honors again in 1989, Hargrove joined the Indians as a big league coach in 1990.

When Indians manager John McNamara was dismissed on July 6, 1991, Hargrove – then the Indians’ first base coach – was named the club’s new manager.

“It’s been a goal of mine since before I stopped playing,” Hargrove told the Associated Press. “I’m very excited.”

The Indians finished the season with a 32-53 under Hargrove but were on the cusp of a new era. With young stars like Kenny Lofton, Albert Belle and Carlos Baerga, the Indians improved by 19 games to 76-86 in Hargrove’s first full season in 1992, then endured a difficult 1993 campaign (that finished with the same 76-86 record) following the Spring Training deaths of Steve Olin and Tim Crews in a boating accident.

Then in 1994, Hargrove and the Indians showed their potential by going 66-47. They were one game out of first place in the AL Central and had a hold on the Wild Card spot when the strike ended the season in August. Hargrove finished second in the AL Manager of the Year voting.

“As a player, I felt bad when we lost,” Hargrove told the Akron Beacon Journal in 1994. “But if I had a couple hits or made a good play, then I could say I did what I could to help.

“But when you’re a manager and your team loses, there is nothing you can feel good about.”

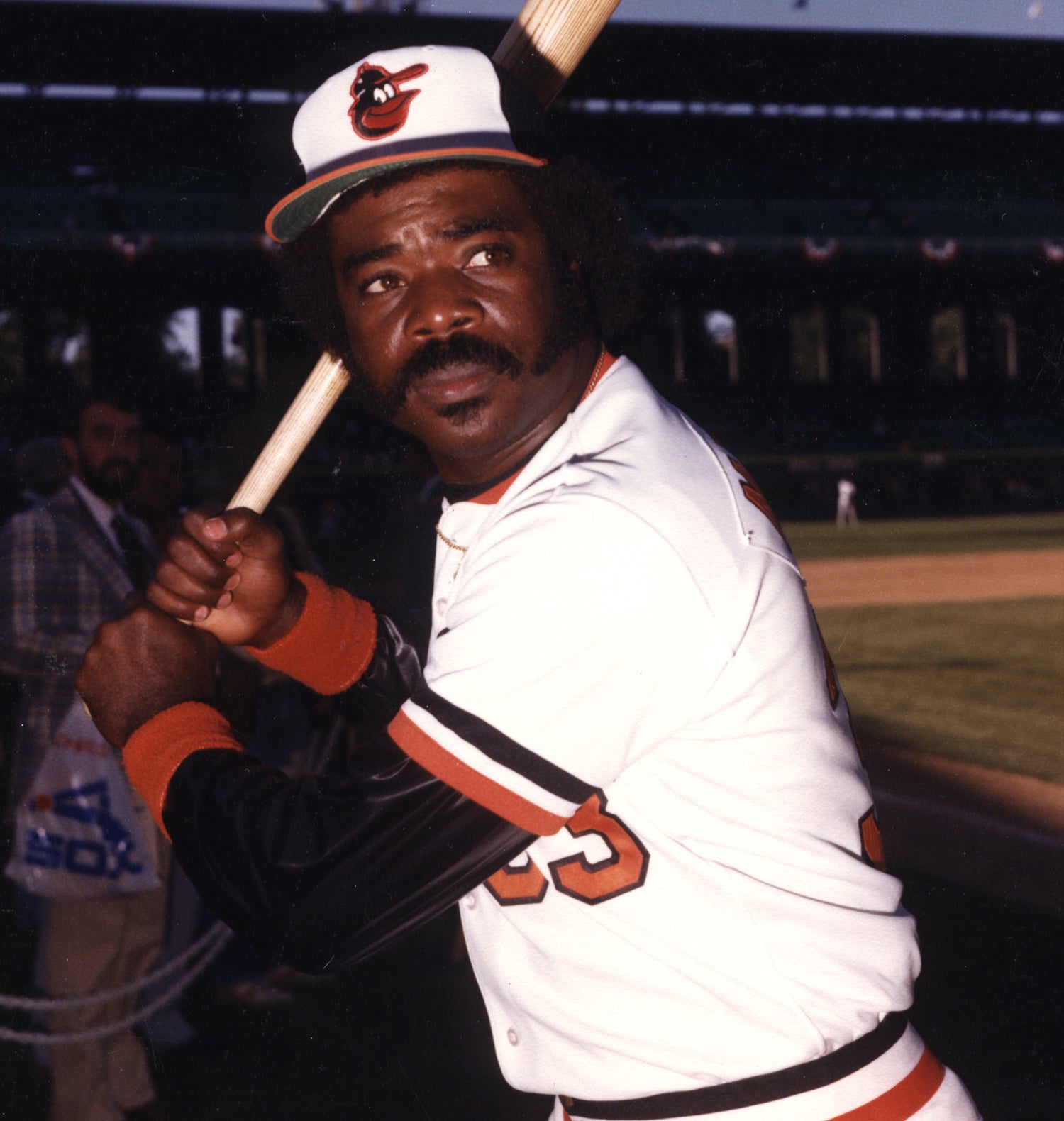

But Hargrove’s team did very little losing over the next few seasons. In 1995, the Indians electrified Cleveland by going 100-44 over the shortened season. Cleveland clinched the division title in early September and rolled into the Postseason, defeating Boston in the ALDS and Seattle in the ALCS before losing the World Series in six games to the Braves.

With an everyday lineup that often featured Manny Ramírez in the No. 7 spot of the batting order, Cleveland outscored its opponents by 233 runs.

“Obviously, he has a lot of talent to work with,” Torborg told the Akron Beacon Journal in 1995. “But he has a lot of – well – I guess you’d call them ‘diverse personalities’ on that team. There are a lot of strong-willed people in the dressing room, and he has done a great job of dealing with them.

“The thing about Mike Hargrove is that if you are around him for a while, you realize that he won’t back down from anyone.”

The Indians won 99 games in 1996 but lost to Baltimore in the ALDS. Then in 1997, a reshaped Cleveland team – which had lost Belle to free agency following the 1996 season and traded Lofton in Spring Training of ’97 – won 86 games to claim its third straight AL Central title.

Cleveland upset the defending champion Yankees in the ALDS and beat Baltimore in the ALCS, but fell to the Marlins in seven games in the World Series.

Hargrove led the Indians to another division title in 1998, and Cleveland then defeated Boston in the ALDS before losing to the Yankees in the ALCS. In 1999, Cleveland went 97-65 to claim its fifth straight Postseason berth – but lost to Boston in the first round.

Soon after, the Indians parted ways with the most successful manager in franchise history – despite the fact Hargrove had one year remaining on his contract. Only Lou Boudreau had more victories in a Cleveland uniform (728 to 721 for Hargrove) and no manager had ever skippered the Indians to more than one Postseason appearance before Hargrove.

“I don’t know of any manager ever getting fired after winning 97 games,” Hargrove told the Washington Post. “But then again, I don’t know of any manager who was rumored to be fired as often as I was over the course of eight-and-a-half years.”

On Nov. 3, 1999, Hargrove signed a three-year deal to manage the Orioles.

“As I told (Orioles owner Peter) Angelos in our interview: ‘I don’t need this job,’” Hargrove told the Baltimore Sun. “But I want this job.”

Hargrove, however, inherited an aging team in Baltimore. The Orioles won 74 games in 2000 and failed to reach that total in each of the next three seasons, costing Hargrove his job.

He was hired to manage the Mariners on Oct. 20, 2004, and improved the club’s record by six wins his first year and nine wins the season after that. In 2007, with the team at 45-33 on July 1, Hargrove abruptly resigned.

“Over the past several weeks, I have come to the realization that to be fair to myself and the team, I cannot continue to do this job if my passion has begun to fade,” the 57-year-old Hargrove said in a statement.

He would not manage in the big leagues again.

Hargrove received votes in the AL Manager of the Year voting each year from 1992-99 but never won the award, finishing as high as second in 1994 and as close as 15 points away from first in 1995. He finished his 16-year managerial career with a record of 1,188-1,173 (.503), which included five first-place finishes and two AL pennants.

Over 12 big league seasons as a player, Hargrove compiled a .290 batting average, 1,614 hits and 965 walks – good for a .396 on-base percentage.

But it was as a manager that Hargrove will be best remembered in Cleveland.

“I think about how the last Indians team I played on (in 1985) lost 102 games,” Hargrove told the Akron Beacon Journal after he was fired as Indians manager. “And the first team I managed (in 1991) lost 105 games. That’s why I feel good about what I accomplished here.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum