- Home

- Our Stories

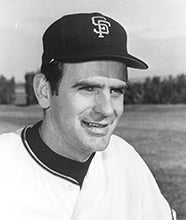

- #CardCorner: 1975 Topps Jim Kern

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Jim Kern

In 1979, Jim Kern compiled a stat line that was the envy of nearly every pitcher in the game.

In a season dominated by relief pitchers like Bruce Sutter, Kent Tekulve and Don Stanhouse, Kern carved out his own place in history with a 13-5 record and 29 saves.

No pitcher since has compiled a season with as many wins and as many saves.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

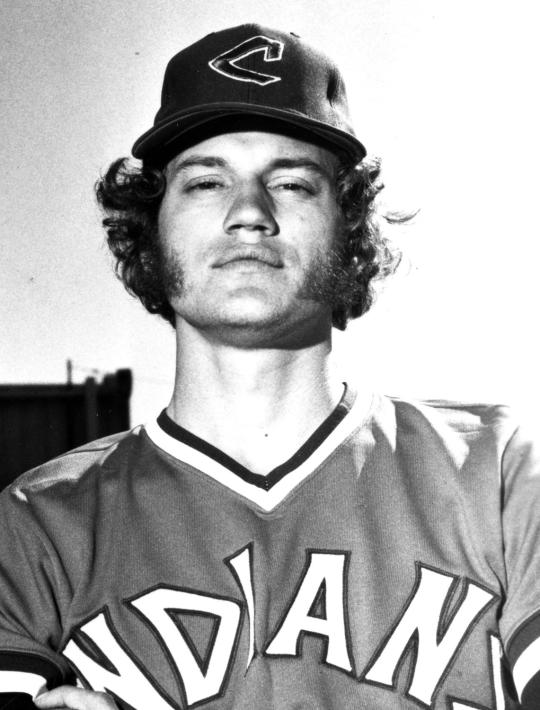

Born March 15, 1949, in Gladwin, Mich., and raised in nearby Midland, Kern took an unusual path to the big leagues. He went undrafted out of high school in 1967, gradually growing into his 6-foot-5 frame. A hard throwing pitcher with little control, Kern impressed Indians scouts when he struck out 43 batters in two games in an American Legion tournament and eventually signed a free agent deal with Cleveland on Sept. 4, 1967 – collecting a $1,000 bonus.

Kern went 4-7 with a 4.93 ERA in 24 games in the Gulf Coast League and the Western Carolinas League in 1968, then joined the Marines in 1969 and did not play that season. But after moving from active duty to the reserves in 1970, Kern decided to give baseball his full attention.

The Indians sent him back to the Western Carolinas League with Class A Sumter in 1970, where he was 5-6 with a 4.88 ERA and a league-leading 25 wild pitches.

“For me,” Kern told the Los Angeles Times, “a no-hitter was when I didn’t hit anybody.”

Kern spent the 1971 season with Class A Reno and was just as wild, striking out 109 batters in 100 innings but also issuing 100 free passes and 27 wild pitches. Promoted to Double-A Elmira in 1972, Kern was 3-11 with a 4.33 ERA with 90 strikeouts in 104 innings.

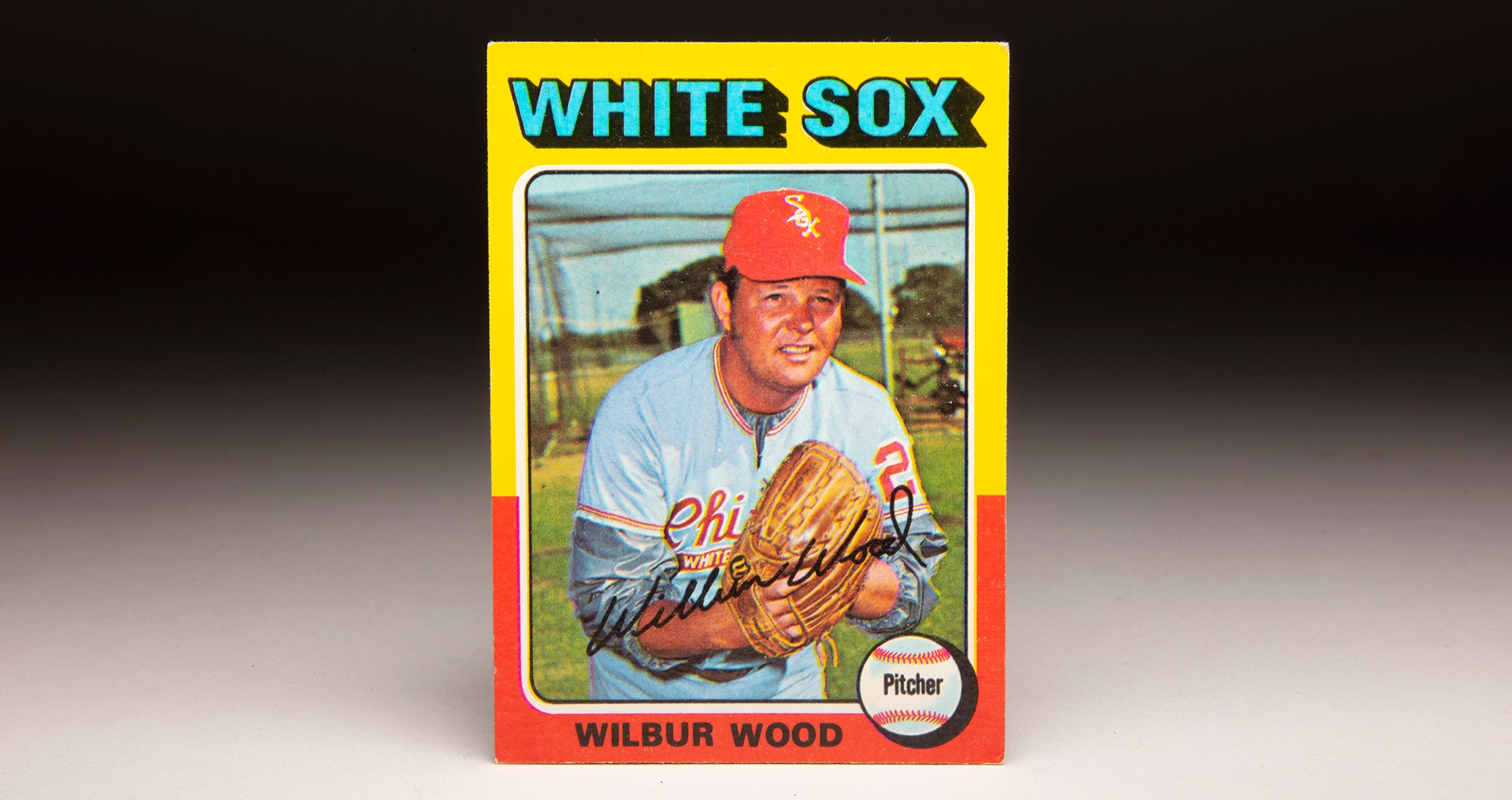

But in 1973, Kern got the break he needed at Double-A San Antonio. Joe Horlen, who had wrapped up his 12-year big league career the year before, was a San Antonio native who made nine appearances that year for his hometown team – mostly as a gate attraction. Horlen, who led the AL in ERA in 1967 with the White Sox, helped Kern harness his fastball and learn to exploit hitters’ weaknesses.

Kern responded with an 11-7 record, a 2.98 ERA and 182 strikeouts in 166 innings.

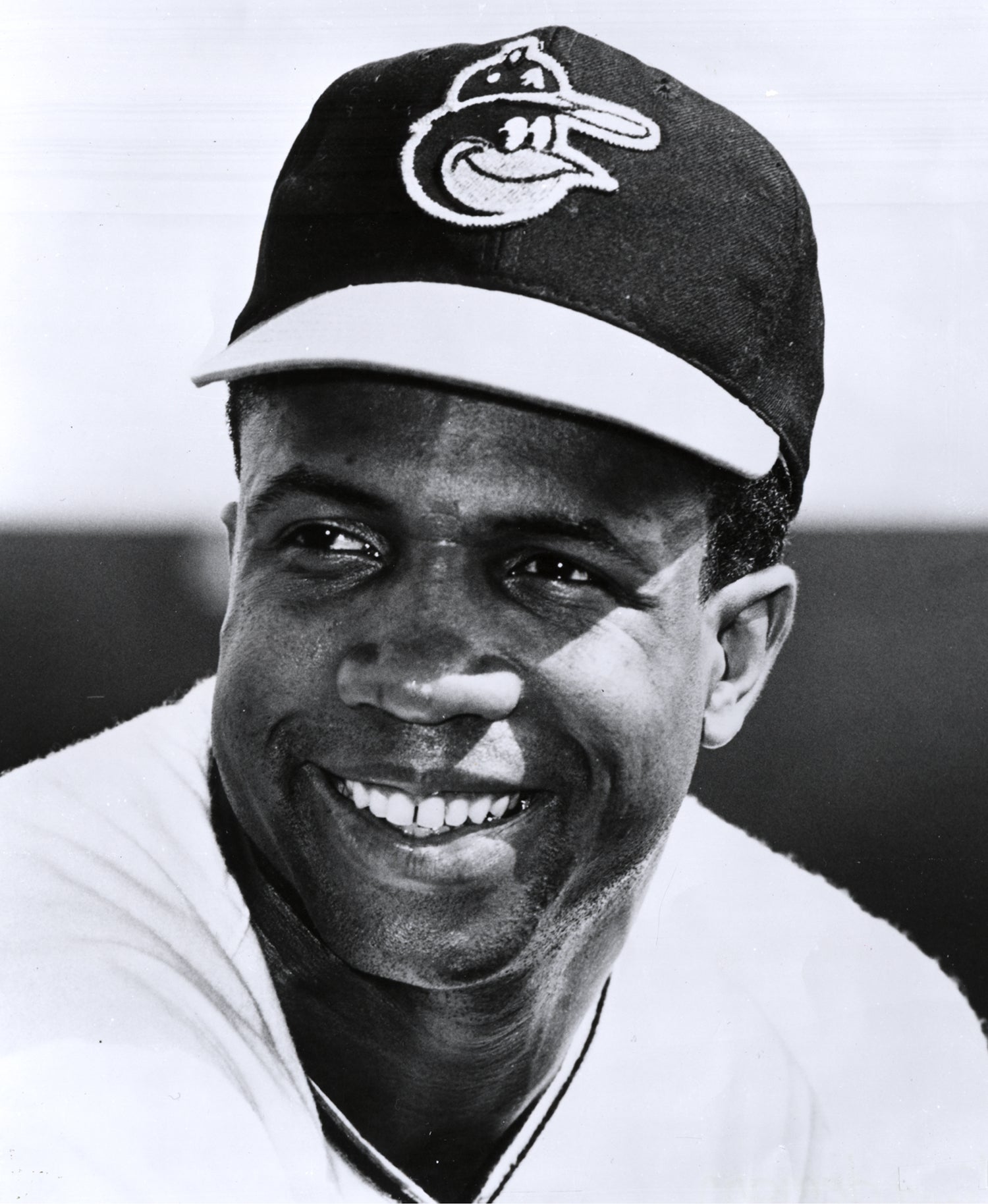

Promoted to Triple-A Oklahoma City in 1974, Kern went 17-7 with a 2.52 ERA and 220 strikeouts. On Aug. 30, Kern struck out 17 batters for the 89ers, three short of the American Association record, in a 9-7 win over Denver. Seven days later, Kern debuted for the Indians – allowing five hits, five walks and one earned run over nine innings in a 1-0 loss to Mike Cuellar and the Orioles.

“The way things are working out, I have to go with the best talent I have,” Indians manager Ken Aspromonte told the Associated Press on the day prior to Kern’s debut. “Kern had an excellent year in Triple-A and throws hard.”

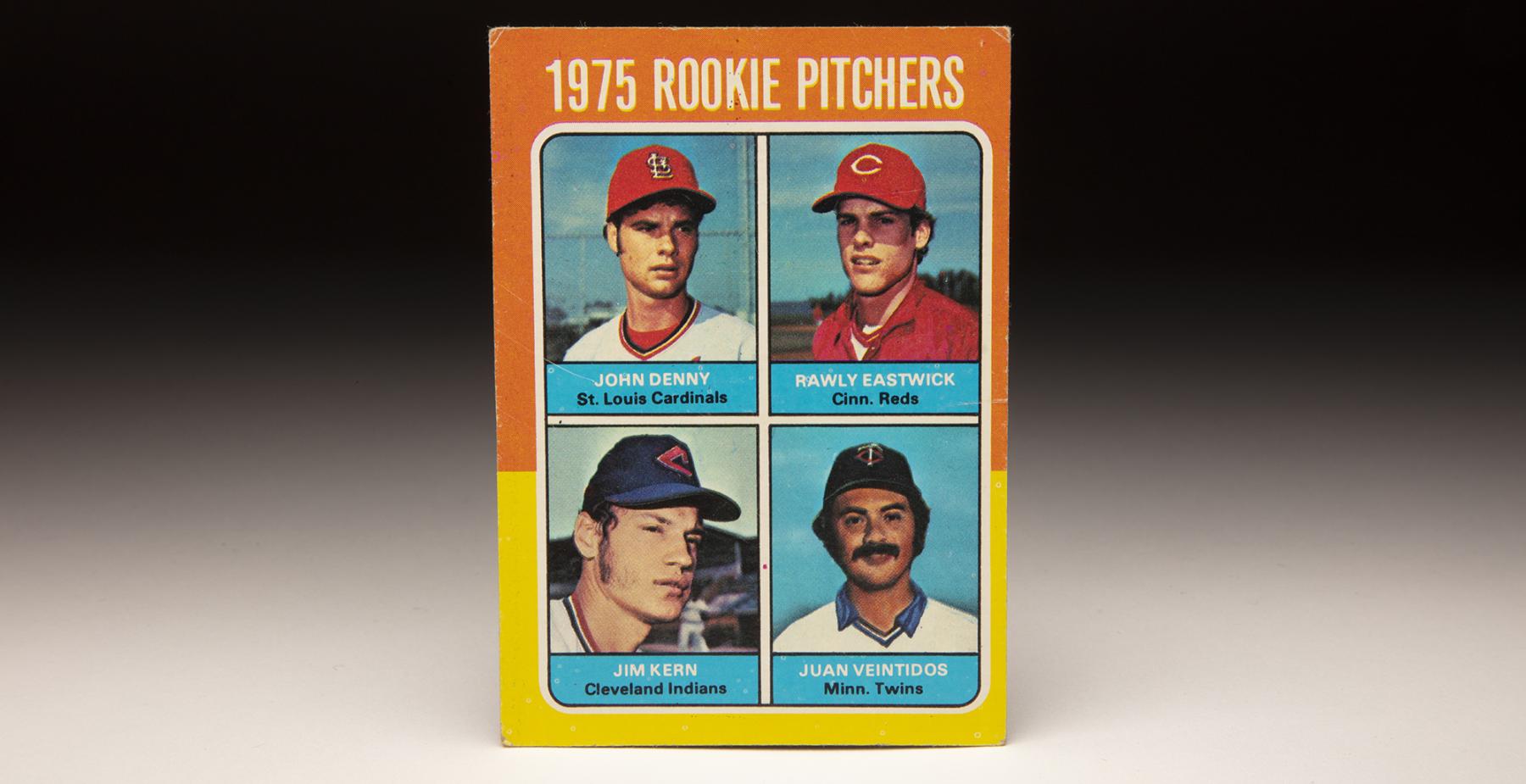

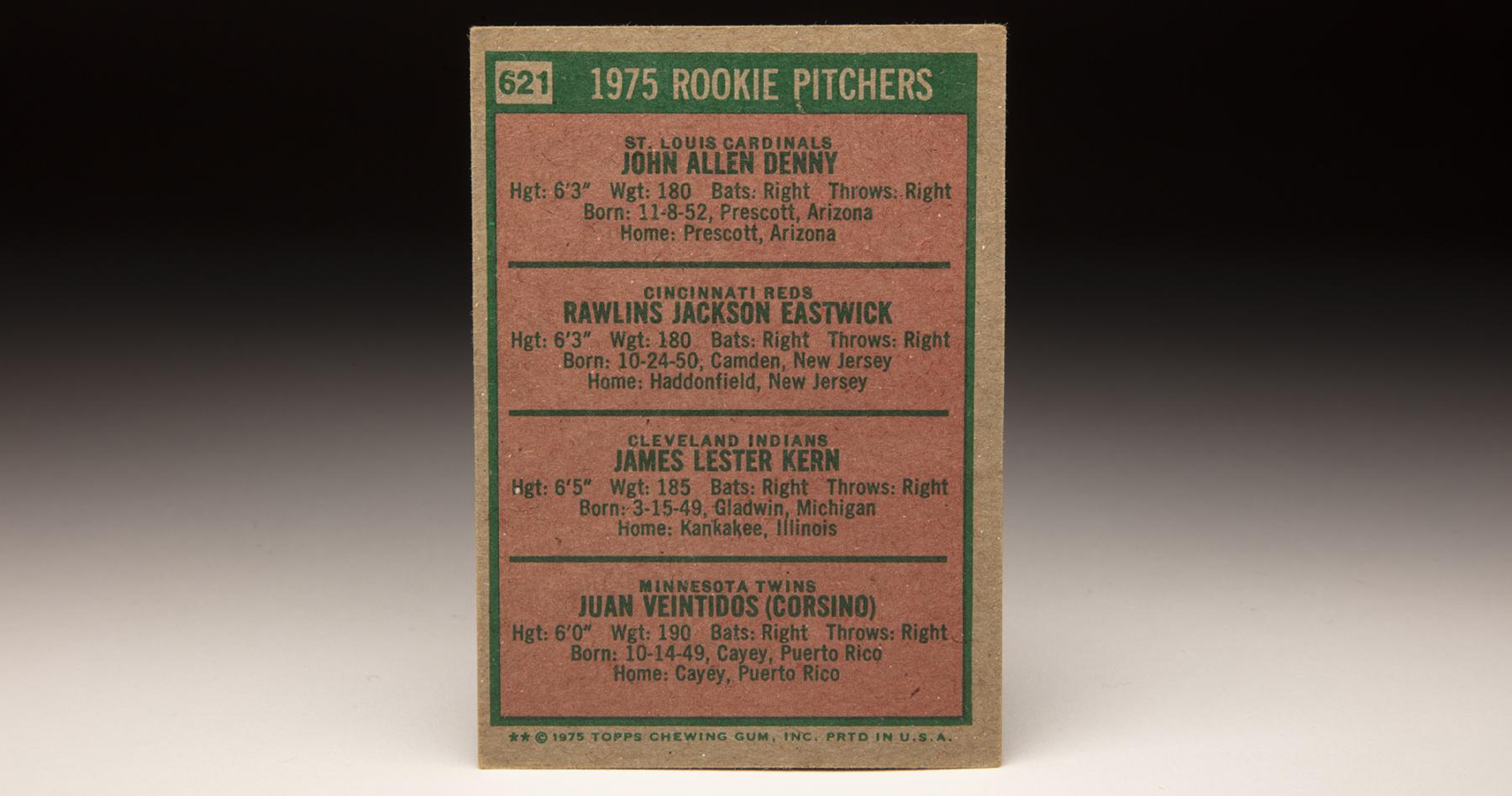

Kern made the Indians’ Opening Day roster in 1975, starting off in the bullpen before moving into the rotation in May. Topps placed him on a Rookie Pitchers card that spring along with future Cy Young Award winner John Denny and Rawly Eastwick, the closer for the Reds’ 1975-76 championship teams.

“If he can get the ball over the plate consistently,” Indians manager Frank Robinson told the Akron Beacon Journal, “there’s no reason he can’t win in the big leagues.”

But after allowing a combined five earned runs over 24.1 innings in his first three starts, Kern began to falter. When the Indians traded Gaylord Perry to the Rangers on June 13 in exchange for pitchers Jim Bibby, Jackie Brown and Rick Waits, Kern was sent back to Triple-A to make room on the roster.

He pitched one more game for Cleveland that year on June 24, then was sidelined for the season with a shoulder injury. But Kern bounced back in 1976, going 10-7 with 15 saves and a 2.37 ERA in 50 appearances, striking out 111 while walking just 50.

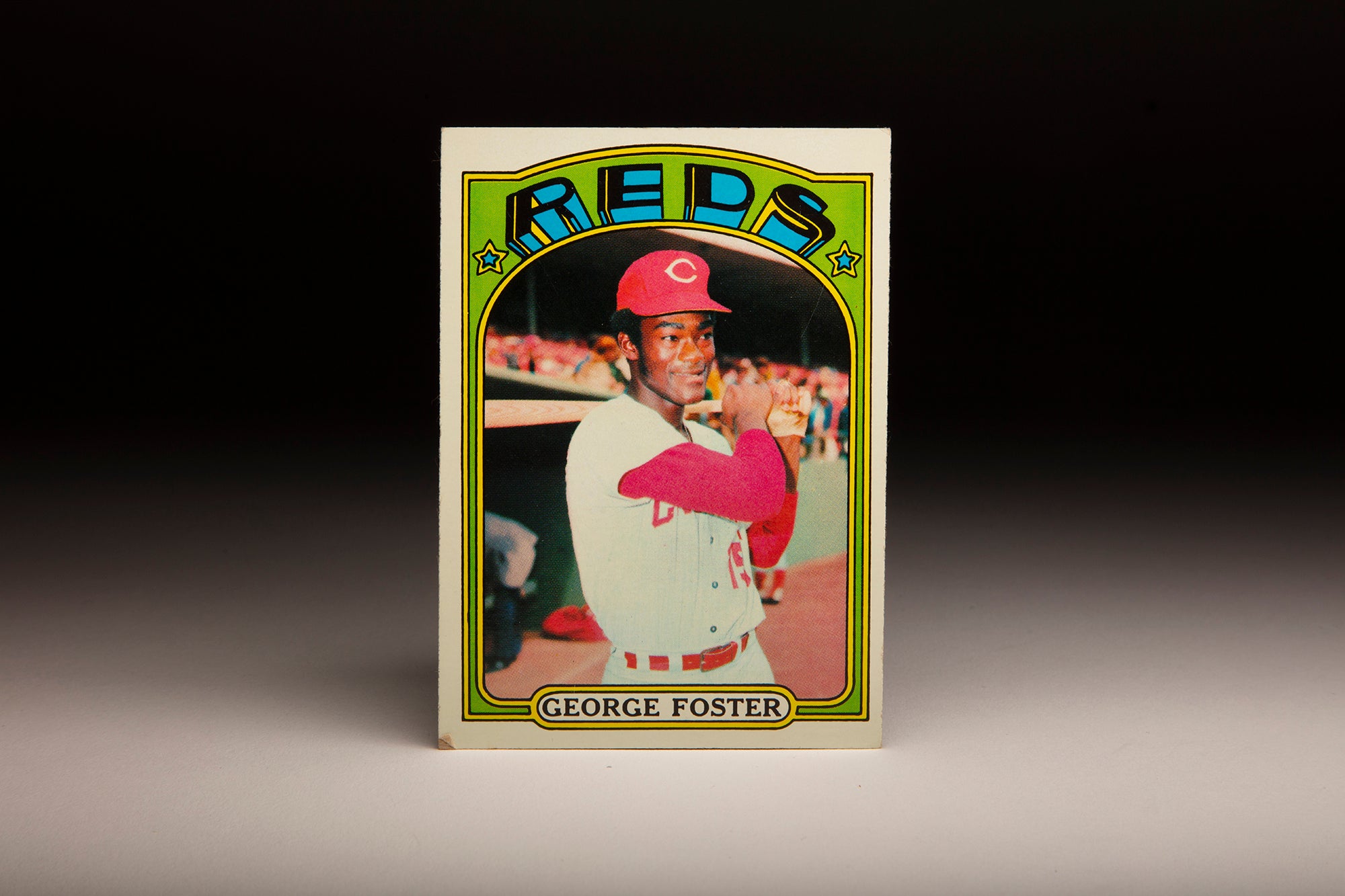

He was named to the first of three straight All-Star Games in 1977, pitching a scoreless inning while striking out 1977 NL MVP George Foster and 1978 NL MVP Dave Parker. He finished the ’77 season with eight wins, 18 saves and a 3.42 ERA, then followed that with 10 wins, 13 saves and a 3.08 ERA in 1978.

By this time, Kern had established himself as one of baseball’s best pranksters, often setting teammates’ feet aflame and waking them up on the road by discharging fire extinguishers. But following the 1978 season, Kern was feeling less than happy about being in Cleveland.

“I always felt like I was excess baggage,” Kern said. “I felt like my talents were never appreciated.”

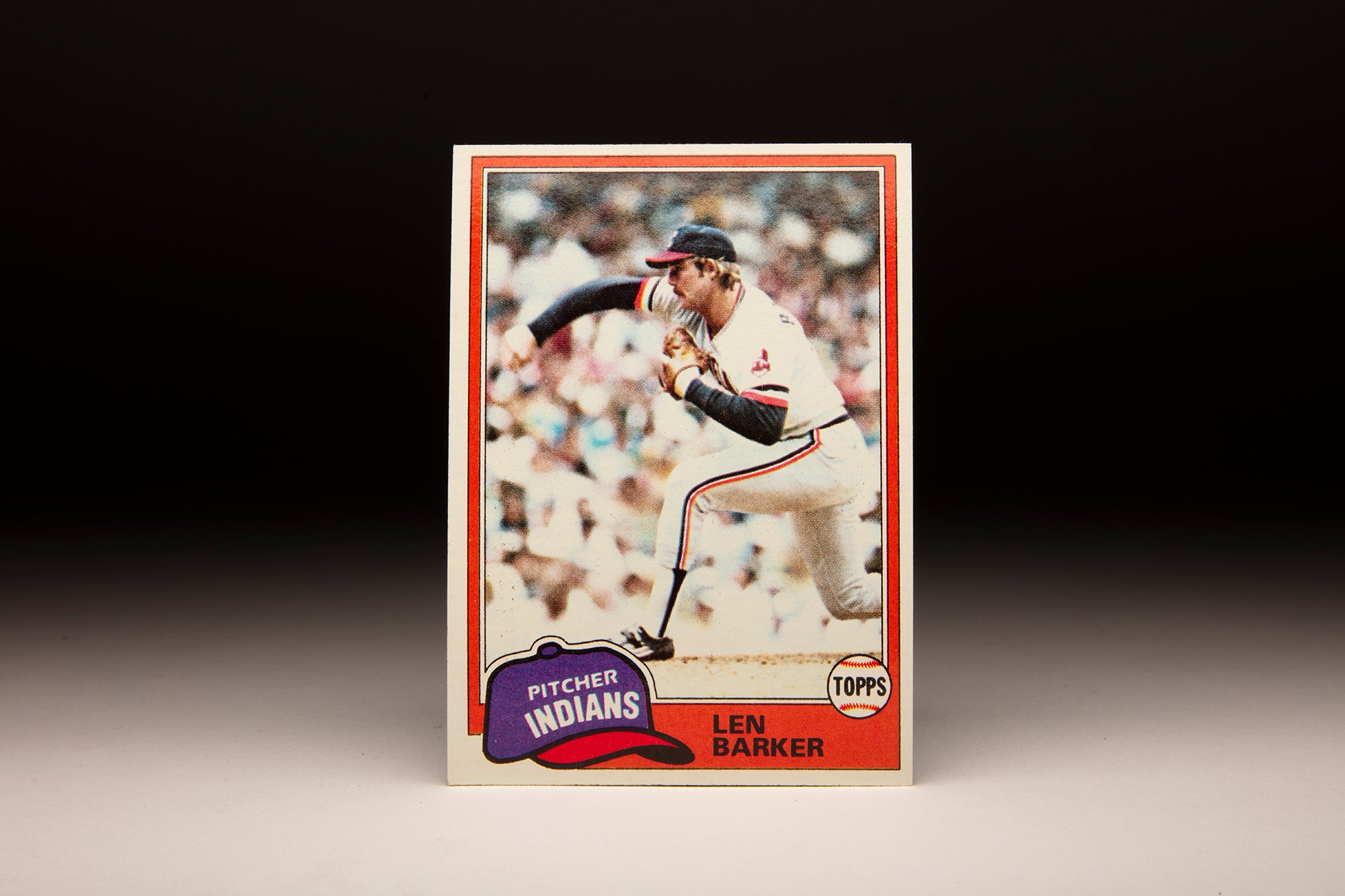

The Indians decided a trade was in order, shipping Kern and infielder Larvell Blanks to the Rangers on Oct. 3, 1978 – two days after the end of the regular season – in exchange for Len Barker and Bobby Bonds.

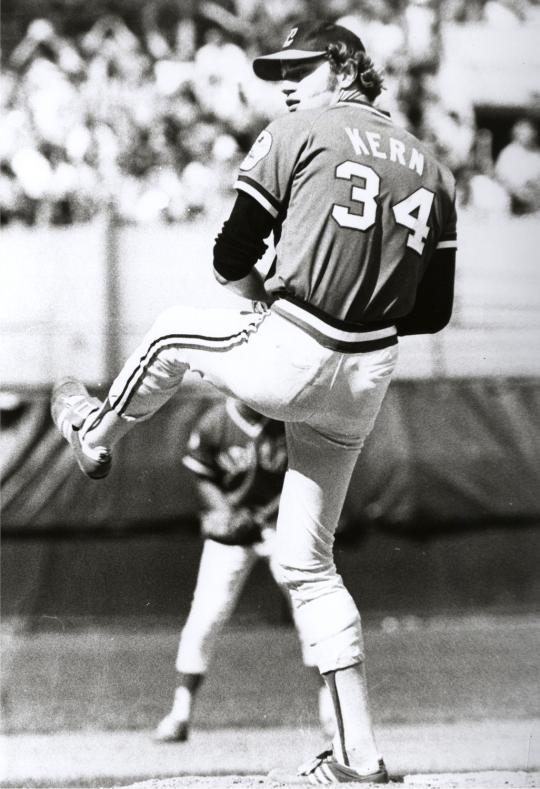

Thus began Kern’s historic 1979 journey when his ERA got as high as 2.57 only one time and he was 10-1 with 13 saves by June 30. Over 71 games, Kern struck out 136 batters and allowed just 99 hits in 143 innings. He finished fourth in the AL Cy Young Award voting, 11th in the AL MVP race and was named the AL Relief Man of the Year.

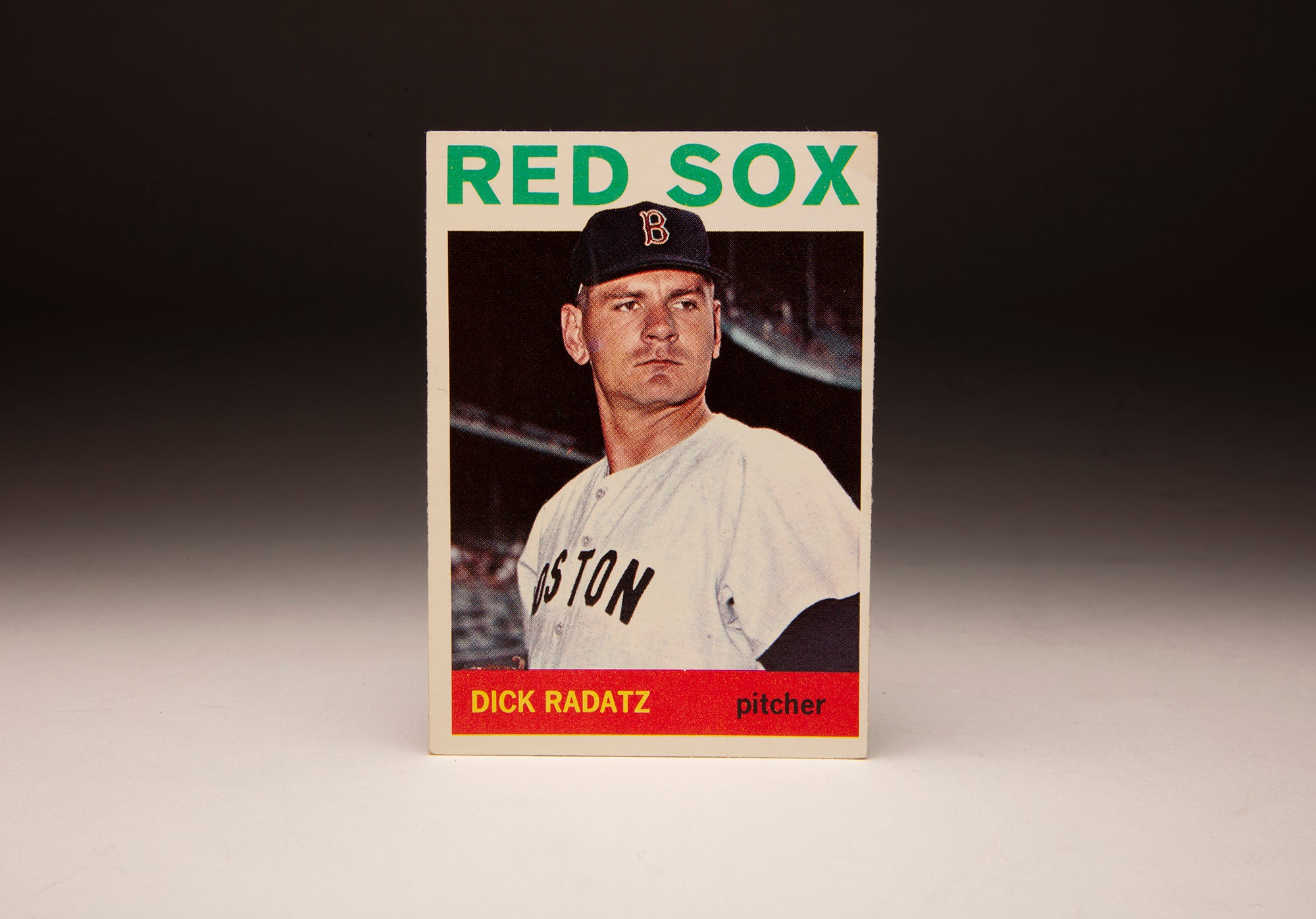

Prior to Kern, only Luis Arroyo (1961), Dick Radatz (1964), Mike Marshall (1973) and Bill Campbell (1977) had posted seasons with at least 13 wins and 29 saves. None had a lower mark than Kern’s 1.57 ERA.

“This is a make-believe world,” the always articulate Kern told the Los Angeles Times in 1979. “In four or five years, my career’s going to come to a screeching halt. You sit back and space out (on success) for a while, but you’re still Jim Kern.”

Indeed, the tide began to turn for Kern in 1980 when he was 3-11 with two saves and a 4.83 ERA in 38 games as he battled elbow and shoulder injuries. Back and neck ailments limited him to 23 games in 1981, though he post six saves and a 2.70 ERA in that strike-shortened season.

But following the season, the Rangers sent Kern to the Mets on Dec. 11 in exchange for Dan Boitano and Doug Flynn. Two months later, the Mets packaged Kern along with Greg Harris and Álex Treviño to acquire Foster, one of the game’s most feared sluggers, from the Reds.

“I’m champing at the bit to throw again,” Kern told the Palladium-Item of Richmond, Ind., following the trade. “I’ve always wondered if I could overpower people over here in the National League. I don’t really care where I’m used – short relief, spot relief or even starting. I just want plenty of work.

“I won’t change my style – it’s pure unadulterated gas.”

Kern pitched well for a Reds team that finished the season with 101 losses, going 3-5 with a 2.84 ERA in 50 games before being traded to the White Sox on Aug. 23 for two players to be named later. Kern was 2-1 with three saves in 13 games for Chicago, then entered the 1983 season with high expectations on a young and talented White Sox squad.

But in his first appearance of the 1983 season on April 5, Kern was pulled after facing just four batters against the Rangers.

“The elbow is a little inflamed,” Kern told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram on April 4. “I’m only throwing 91 to 92 (mph).”

Kern tore a muscle in his right arm during the game, necessitating surgery and ending his season. Released by the defending AL West champion White Sox on March 1, 1984, Kern joined the Phillies in June but was let go a month later before hooking on with the Brewers toward the end of the year.

He appeared in just 14 games in 1984, five (with the Brewers) in 1985 and 16 (with the Indians) in 1986 before his career ended.

He was given his release by the Indians on June 17, 1986.

“I had my opportunities,” Kern told the Akron Beacon Journal after posting a 1-1 record and 7.90 ERA. “I was only going be here until the (young Indians players) matured. My problem was that they matured too fast.”

Kern finished his career with a record of 53-57 to go with 88 saves and a 3.32 ERA over 416 big league appearances. But for one year in Texas, Jim Kern was among the best relievers of his era.

“If you think being a ballplayer makes you a better person than anybody else,” Kern said, “you’re in a lot of trouble.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum