Collins revered as one of game's best second basemen

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

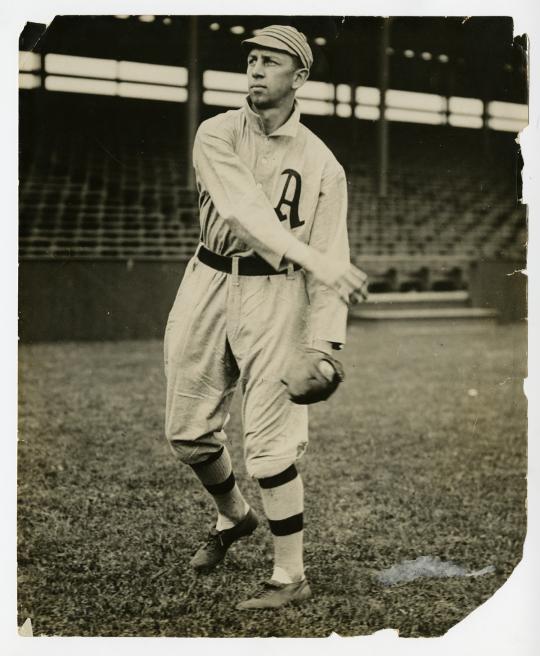

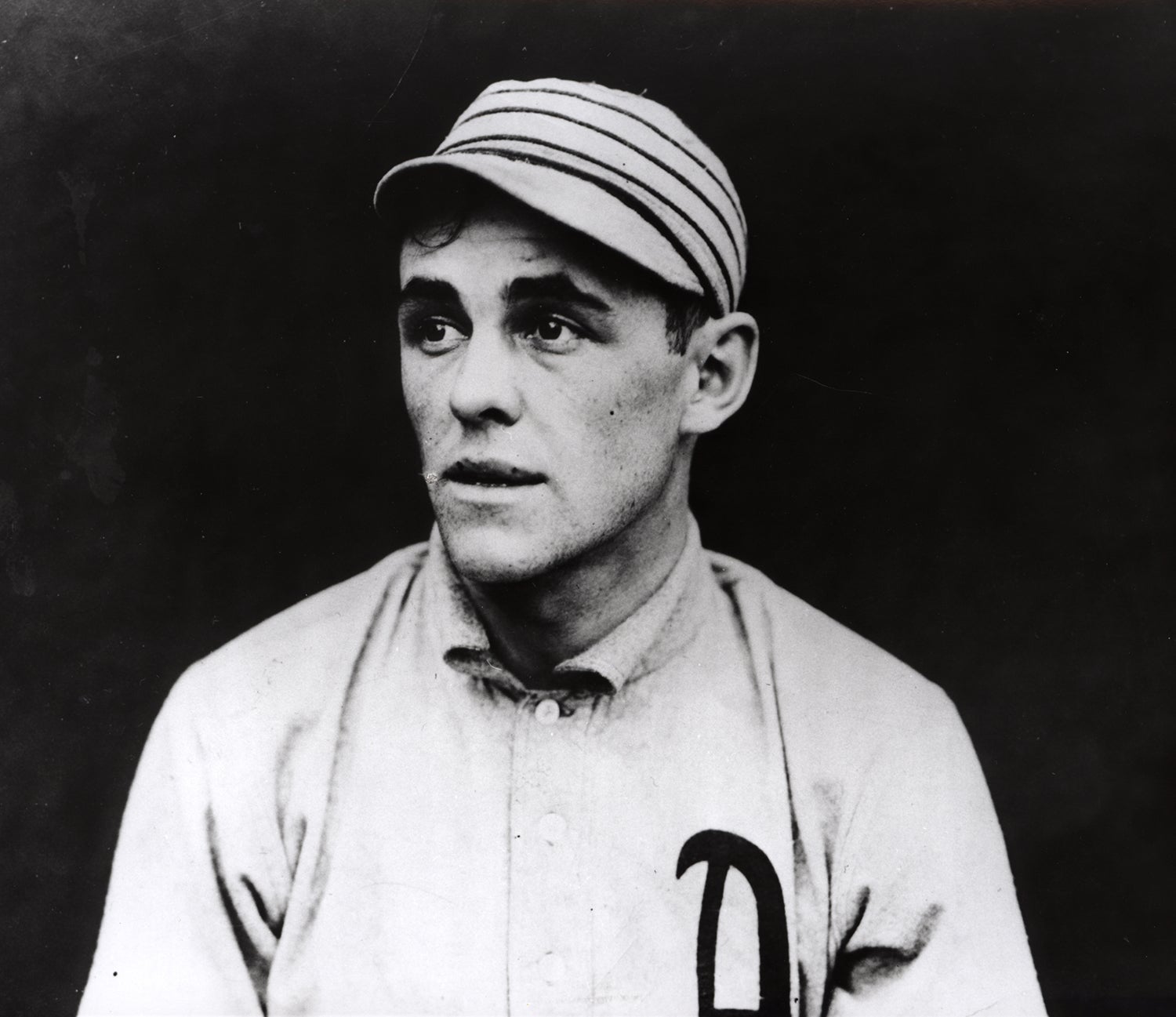

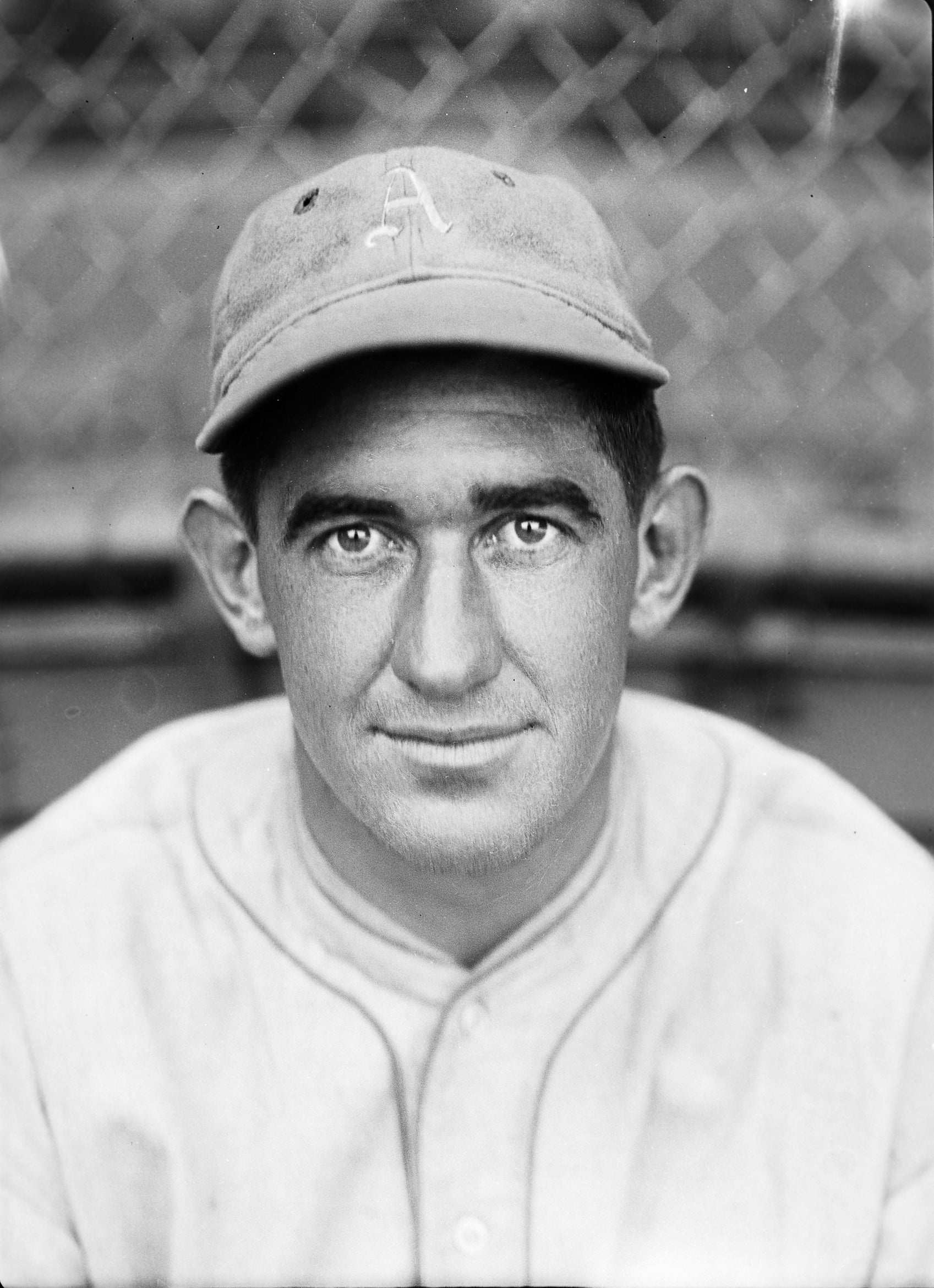

Collins split his big league career between the Chicago White Sox and Philadelphia Athletics. The Columbia University graduate finished with an impressive 3,315 hits, a .333 batting average and 741 stolen bases.

Even at an advanced age, as far as ballplayers go, Collins was still putting up pretty remarkable numbers. Between the 1923 and ’27, Collins’ age 36-40 seasons and the last years he was still seeing significant playing time, he compiled during this five-year stretch a .349 batting average and a .452 on-base percentage, striking out only 49 times in 2,087 at bats while collecting 378 walks. In fact, Collins was a keen-eyed batsman throughout his long and storied career, finishing with a .424 on-base percentage that currently ranks 13th on the all-time list.

“There is a great deal in knowing when to hit,” Columbia Eddie wrote in The Boston Globe in 1911. “By this I mean it is to the advantage of some batters to play a waiting game and make the pitcher go the limit. For instance, if the count is two balls and no strikes, certain batters never will offer at the next ball thrown. Likewise, if it stands ‘ball three and strike one,’ nine times out of 10 the next ball will go by unmolested.

“Men … whom are diminutive of stature and for this reason have the advantage over the pitcher and can afford to pursue such a course. But for the average individual under the above mentioned conditions I would say, hit.”

A few years later, Collins penned, “Personally, I am tickled to death when I get a free pass because it gives me and awful swell opinion of myself that somebody really would rather take a chance on Home Run Baker of Stuffy McInnis.”

Baker, the third baseman, first baseman McInnis, along with shortstop Jack Barry, joined Collins as part of the famed “$100,000 infield” of the Athletics back in the years before World War I. The quartet was broken up when the 27-year-old Collins was sold to the White Sox after the 1914 campaign for a then-unheard-of $50,000.

William A. Phelon, in a 1915 edition of Baseball Magazine, wrote, “The batting and base running power of Collins, added to his fielding skill, make him about the most valuable second sacker that has ever capered in the major leagues… Collins is not a large man, nor possessed of remarkable strength, but he has a batting eye, an accuracy of judgment when it comes to picking them out, like that of the tiny Keeler. Collins, like Keeler, hits left-handed, but Keeler is a left-hand thrower, while Collins, like Cobb, is what might be styled an artificial or educated left-hand hitter – throwing right-handed. I fail to recollect a single serious batting fault in the Collins style. Fact is, I don't just now remember any faults at all. He hits a fair share of long, extra base biffles, and inserts the short, emphatic singles at the time they are needed most. With men on bases, and when his team is tottering to defeat, darkness closing in, two down, a couple of runs imperative - that's when Collins has always risen supreme, superior to every handicap.”

Pitcher Jack Quinn, a longtime American League foe who later teamed with Collins on the A’s of the late 1920s, once said of the keystone star, “Eddie hasn’t merely been my jinx, he’s the hardest man to pitch to I’ve ever faced. Eddie has a keen eye and if the ball is an inch off the plate he takes it. He waits until the last minute before swinging and then comes into the ball snappily.”

EDDIE COLLINS

(appeared in Baseball Magazine, March 1915)By W.A. Carlson

He's a daisy, he's a dandy,

He's a wonder at the game,

He's a corking second-baseman;

Every rooter knows his name.He's a peach at stopping grounders

As they skim across the dirt;

He's chockful of pop and ginger,

And he plays for all he's worth.He is just as good as Evers

When it comes to brain and wits,

And he is just as fast as Milan

At beating infield hits.They may talk about Joe Jackson,

Tyrus Cobb and all the rest,

But when it comes to picking stars,

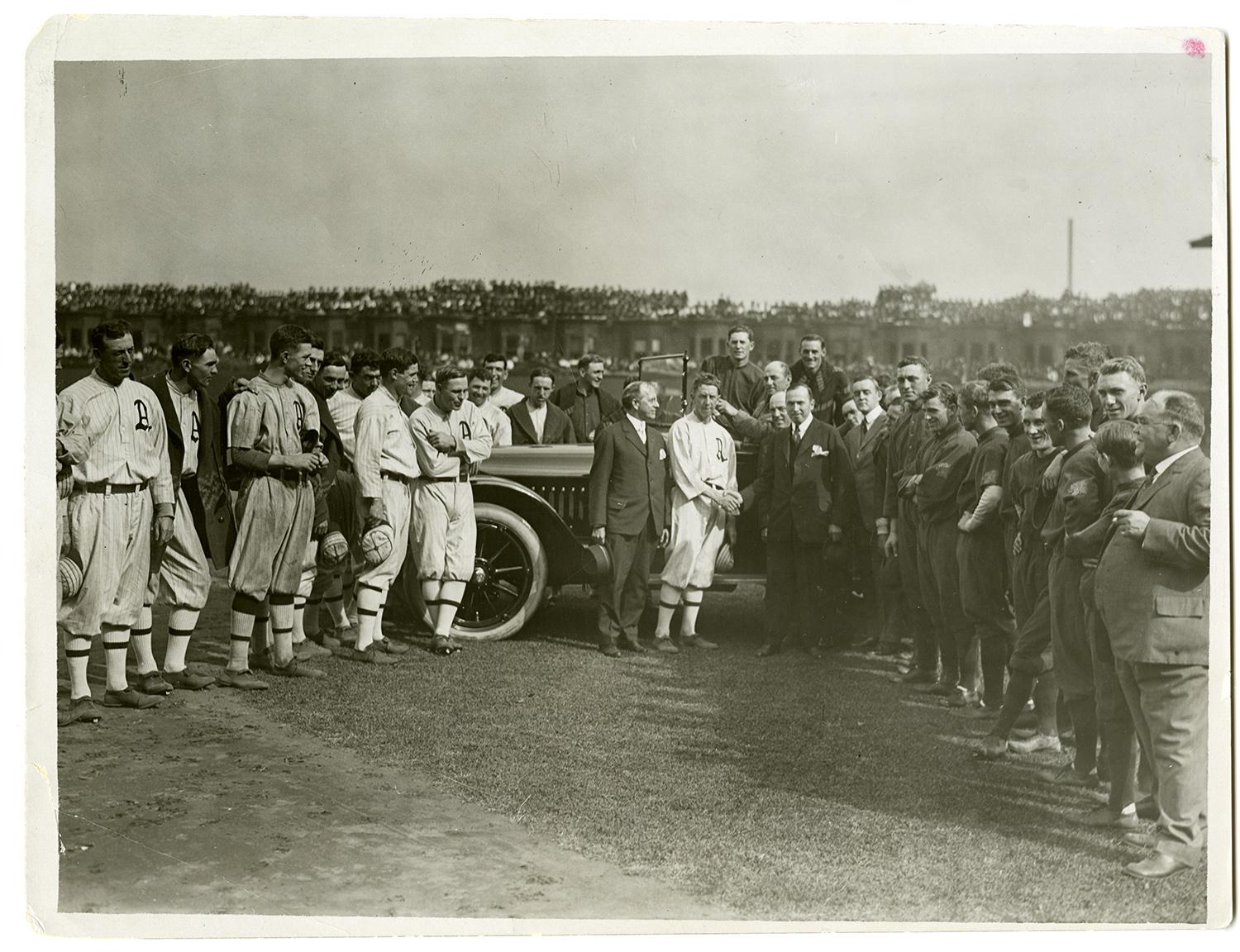

We'd pick Collins with the best.Last year he won the Chalmers car,

He well deserved the same,

So, here's hats off to Eddie Collins;

He's a credit to the game.

No less an authority on baseball than manager John McGraw, whose New York Giants lost twice times to Collins-led teams in the World Series, called the second baseman the world’s greatest player after leading the Athletics past his team, four games to one, in the 1913 Fall Classic. This despite McGraw having seen the likes of Ty Cobb, Honus Wagner, Nap Lajoie, Willie Keeler, Cap Anson and others grace the ballfield.

“I want to go on record as saying that Collins is the greatest ballplayer in the world. He showed it in this series,” said McGraw of Collins, who batted .421 in the 1913 World Series. “Ty Cobb may mean more in the box office because of his ability as a drawing card, but Collins win more ballgames for a club, which is what counts in my mind.

“He made a great many plays in this series that the spectators in the stands may have missed, but which were very apparent to me. Besides his individual work, he keeps the club on edge and thinks for many of the other players. He is a steady and brilliant fielder, getting balls that no other second baseman would try for. He also is one of the fastest thinkers I have ever watched, judging plays and executing them with great accuracy. Besides his fielding, he is easily the most dangerous hitter on the club, as is shown by his work in the series just closed. They may talk about Baker and the rest of them, but Collins is the most damaging in a pinch.

“Collins is not playing for individual glory, which is what I like about him. He is always ready to dump down the bunt when that looks like the play. He is also very aggressive, and has so much pepper that he keeps all the rest of the team in its toes. He is a finished ballplayer of the thinking type, and, to my mind, the greatest in the world. What makes me sore every time that I look at him is to think of him playing at Columbia and getting away from me because his family wanted him to study law, and not play baseball. It was Connie Mack who persuaded him otherwise, and he has a world’s series title as a result, for Collins was the principal factor in winning the first, third and fifth games of the series.”

According to McGraw, he went over and shook Collins’ hand after the final game of the 1913 World Series.

“’You are the greatest player in the world, to my mind,’” I told him. “’They may talk about Cobb, but I would rather have you,’” McGraw said. “He seemed embarrassed by my praise. He is a great young fellow.”

A participant in four World Series with the Athletics and two with the White Sox, Collins finished with a .328 batting average in the Fall Classic.

“Who is the greatest money player in the world? That is a soft one, Eddie Collins by a whole city block, and a couple of apartment houses thrown in,” said AL umpire Billy Evans in 1919. “There is no room for argument on that point. By money ballplayer it is meant the player best able to do big things at the most crucial moment.”

Kid Gleason, who managed the White Sox with Collins on the team from 1919 to 1924, added: “Eddie Collins is the greatest player I have ever seen in my long career, and I have seen a lot of them. Never saw him do a dumb thing in his life, and incidentally he is forever keeping some of his teammates from making a slip.”

“Collins is the greatest second baseman I ever saw,” said star second baseman Johnny Evers after his Cubs lost to the A’s in the 1910 World Series. “Darned if I can explain why he is, but he IS, just the same!"

Near the end of Collins’ career, the esteemed writer Grantland Rice attempted to put the second baseman’s career in historical perspective.

“There is still a strong argument as to whether Eddie Collins must be listed as the greatest of all-time second basemen,” Rice wrote. “He could not quite hit with Lajoie, but he could outhit Johnny Evers, another leading rival. Collins combined more stuff than either Lajoie or Evers. He was smart, shrewd, fast, a brilliant infielder, a fine baserunner and always a dangerous hitter. He was faster than either Lajoie or Evers and at his peak came as close to combining all the qualities as any rival star you can name.”

When longtime A’s manager Connie Mack picked his all-time team in 1930, the second baseman he chose was Eddie Collins. “In selecting Eddie Collins for second base, I want to point out that he was a great batsman, one of the best players defensively and a daring baserunner. Then he topped all these things by being the brainiest player that ever guarded the keystone, in my estimation.”

After his playing career, Collins, elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939, worked for the Red Sox as Red Sox as a general manager and vice president until his death in 1951 at the age of 63.

“Eddie Collins inscribed many outstanding performances on the game’s records,” read a Sporting News editorial soon after Collins’ death. “He also gained the enduring esteem and affection of all who knew him.

The game is all the better for his 45 years of participation as player, manager, coach and club executive.”

Bill Francis is a Library Associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum