- Home

- Our Stories

- The Taylors, including Hall of Famer Ben Taylor, helped define a generation of baseball in the Negro Leagues

The Taylors, including Hall of Famer Ben Taylor, helped define a generation of baseball in the Negro Leagues

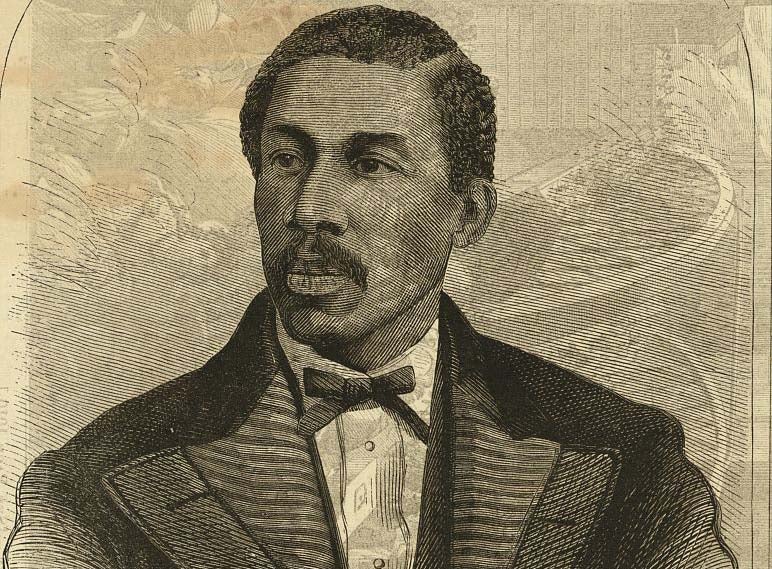

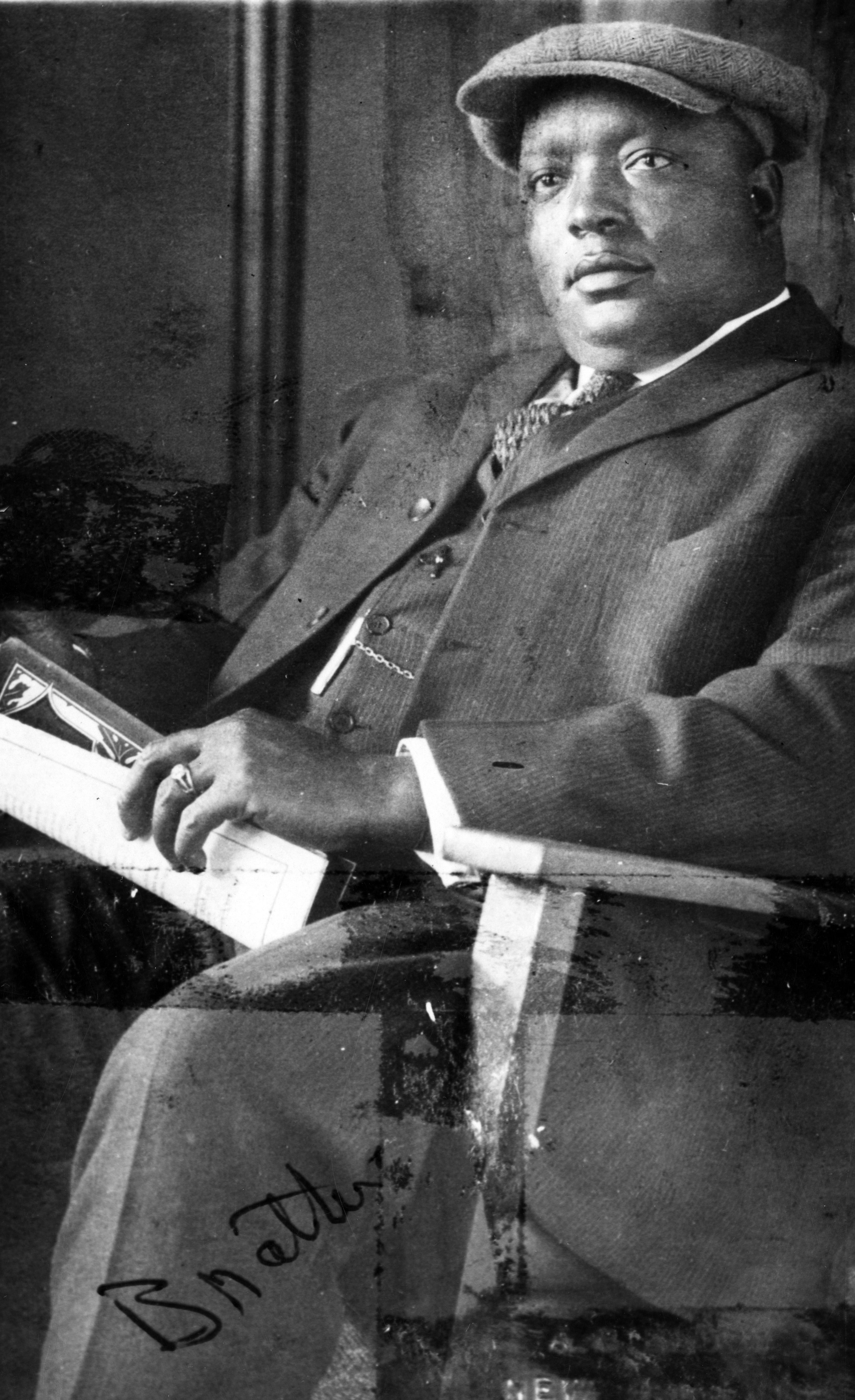

First came Charles Isham Taylor, born to Isham Taylor and Adeline Hayne in Anderson, S.C., on Jan. 20, 1875.

Then there was John Boyce Taylor, born in Anderson on Aug. 12, 1879.

James Allen Taylor arrived four and a half years later, on Feb. 1, 1884.

And Benjamin Harrison Taylor was born on July 1, 1888.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

All told, the Taylors had nine children – three daughters and two other sons. It was enough to field their own baseball team, but it was these four men who made a name for themselves on the diamond.

Known now as the “first family” of Negro Leagues baseball, the Taylor name is scattered throughout decades of box scores and news clippings.

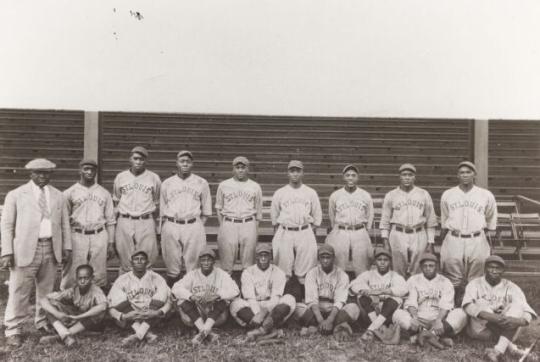

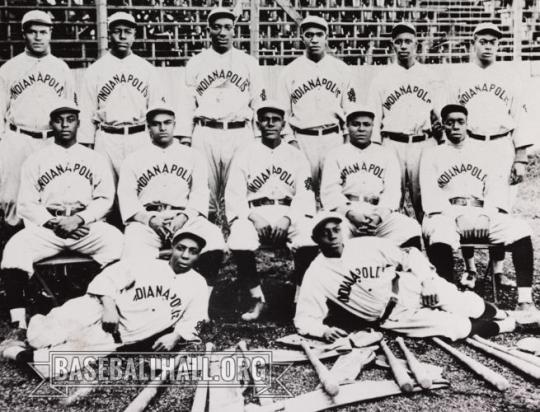

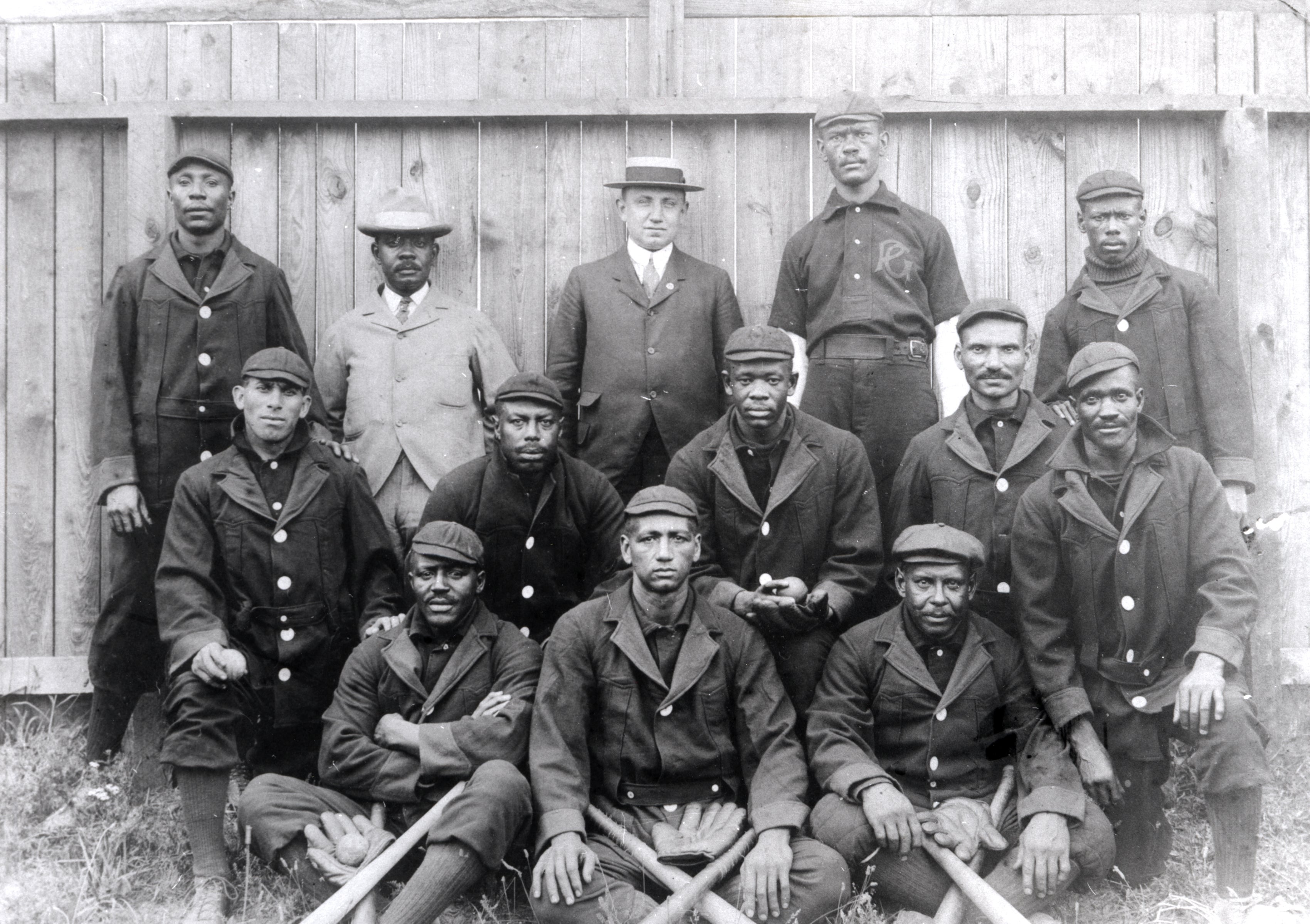

Charles Isham, who went by C.I., led the way for the brothers. He played second base for Clark College and served as a member of the Tenth U.S. Cavalry Regiment in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War. Upon returning to the United States, C.I. began his baseball career in earnest. He was a major proponent of organized baseball, and in 1904 founded the first all-Black professional team in Birmingham, Ala.: The Birmingham Giants. “[He] wanted organized baseball and he went to his death trying to get it,” wrote the Pittsburgh Courier decades later in 1931. “C.I. Taylor can rightfully be called the father of the ideas of organized baseball among colored players.” After six seasons in Birmingham, C.I. moved the Giants to West Baden, Ind., and renamed them the Sprudels, and in 1914 moved them once more to Indianapolis. It was there, upon sponsorship by the local American Brewing Company, that they were called the ABCs and went on to become a perennial powerhouse. The eldest Taylor’s managerial career spanned 19 seasons and he was widely regarded as one of the greatest managers of his era, with a knack for teaching his players excellence on the field and exemplary character off it.

John Boyce got his start at Biddle University in Charlotte, N.C., where he pitched and earned the nickname “Steel Arm Johnny.” He joined C.I. in Birmingham, demonstrating his talent and durability by maintaining a six-season streak wherein he started upwards of 30 games a year but never lost more than seven outings in a season. He pitched for 17 seasons, including stints with C.I.’s ABCs, as well as the St. Paul Gophers, Chicago Giants, St. Louis Giants, New York Lincoln Giants and Chicago American Giants. Johnny also joined his younger brother, Ben, in 1924 as the pitching coach for the Washington Potomacs.

James Allen, like his brothers, earned a distinctive nickname – Candy Jim – during his decades in the game. Jim began playing baseball while attending the Greeley Institute, then joined his brothers in Birmingham in 1904 and later in West Baden, before teaming up with Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants. His younger brother, Ben, joined him in Chicago – and with their help the American Giants remained atop the standings.

The 1914 season saw a Taylor Brothers reunion in Indianapolis, with Ben and Jim joining C.I. and Johnny on the ABCs. They were a dynamic quartet: Jim and Ben hit third and fourth in the lineup, Johnny was an ace and C.I. managed and pinch-hit. Jim left the ABCs after the season but returned two years later and helped them defeat his former American Giants for the western championship title.

Injuries hampered Jim's playing career, but the infielder played well into his 40s as a player-manager, most notably for the St. Louis Stars, Chicago American Giants and the Negro World Series-winning Homestead Grays. Reports differ about whether he managed the inaugural East-West Game in 1933, but we do know he managed the West team twice and the East team once in later years.

Unlike his brothers more colorful nicknames, Benjamin, the youngest of the quartet, went simply by Ben. He too got his start with C.I. and the Birmingham Giants, debuting as a pitcher in 1908 – but it was his play at first base where he gained notoriety as one of the finest in the game. He was meticulous in his approach to hitting, known for his ability to hit the ball to all fields and for his execution of the hit-and-run. These offensive talents earned him the nickname, “Old Reliable,” in recognition of his steady excellence at the plate and at first.

Ben followed C.I. up north when the eldest brother relocated the Giants and had a two-season stint with the St. Louis Giants before joining Jim and Johnny in Chicago, where the three played on Foster’s 1913 Chicago American Giants. He signed on with C.I. again in 1914 and played for the ABCs until 1922, during which time the lowest his batting average ever dipped for a season was .294. Ben took over managerial duties for Indianapolis in the season after C.I. died, and later served as player-manager for the Washington Potomacs, Baltimore Black Sox, Harrisburg Giants and Bacharach Giants. Fellow Hall of Famer Buck Leonard credited Ben with teaching him the game, noting “I got most of my learning from Ben Taylor. He helped me when I first broke in with his team. He had been the best first baseman in Negro baseball up until that time, and he was the one who really taught me to play first base.” Similarly, after Ben passed away in 1953, the Chicago Defender described him as “One of the great first basemen in Negro baseball. His name is bracketed with that of other top first sackers of that period. He was an excellent fielder and a cracking good hitter from the left side.” The Taylors were a familial baseball dynasty for the ages.

Isabelle Minasian was the digital content specialist for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum