- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Rube Foster’s home team

#Shortstops: Rube Foster’s home team

Wrigley Field and the Cubs.

Fenway Park and the Red Sox.

Dodger Stadium and the Dodgers.

For many baseball fans, their connection to their team’s home ballpark is nearly as strong as their attachment to the team itself. The bond creates a sense of community, a space to gather together and build memories for new and old fans alike.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

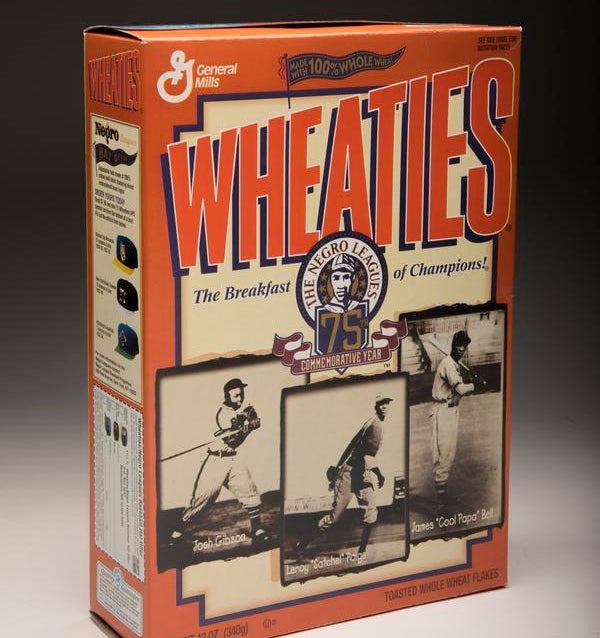

For Black baseball teams – both before and after the founding of the Negro Leagues - the absence of a home field did not simply keep them from building a stronger fan base. It was yet another barrier that potentially kept them from playing the game at all.

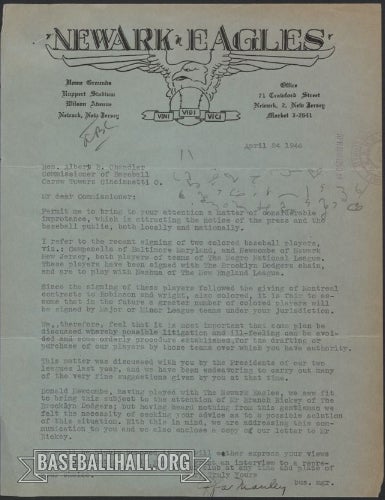

A series of correspondences between African-American team owners and the Cincinnati Reds organization are preserved in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s archives, and demonstrate the often-frustrating realities these teams faced before they could even take the field. Most notable are the letters exchanged between Karl Finke – son-in-law of Reds’ President August Herrmann and the team’s longtime auditor – and Rube Foster.

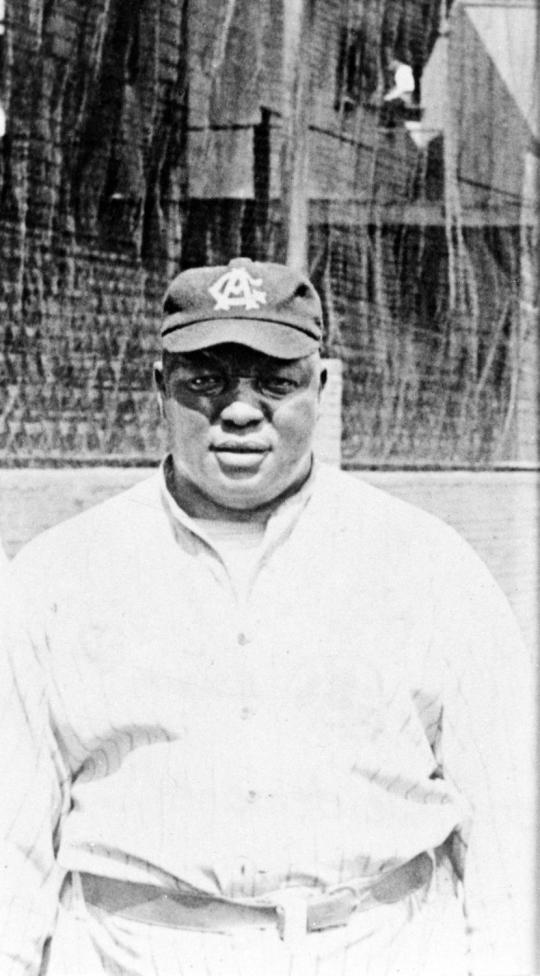

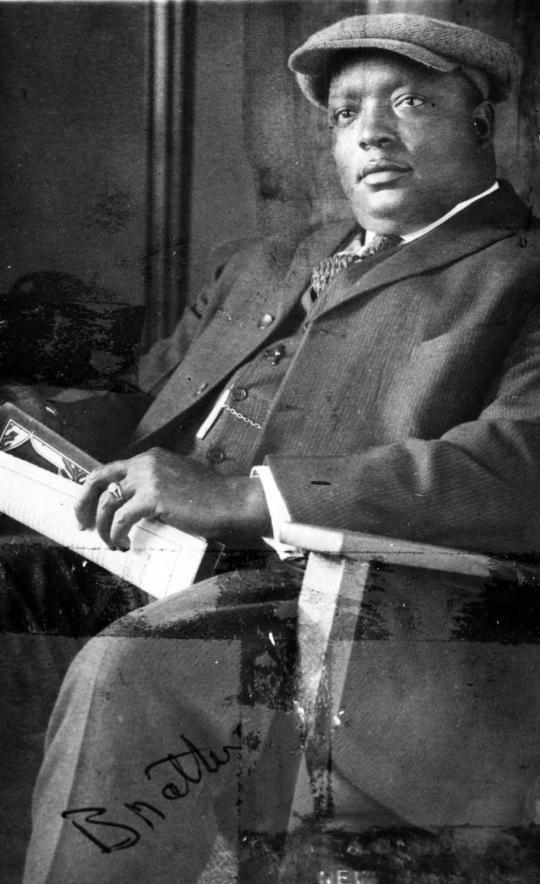

Foster, who was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1981, was regarded by many as the “father of Black baseball.” He began his baseball career as a player, pitching successfully for a number of seasons during the Deadball Era, but it was as a leader and executive that Foster truly left his mark.

In 1910 he formed the Chicago American Giants and, as pitcher-manager, led the young team to a staggering 128-6 record. Next season, he secured a partnership with John Schorling, the son-in-law of White Sox owner Charles Comiskey, wherein Schorling provided the field – the Sox’s old South Side Park – and Foster provided the players. The Giants became one of the most prominent Black teams in baseball.

This partnership did not limit Foster’s team to South Side Park, though, as evidenced by letters from Foster to Finke in 1917. His language in these letters is exacting; the writings of a shrewd businessman dedicated to his organization. On prominent American Giants letterhead, Foster proposes a series to take place at Redland Field, between his Giants and the Cuban Stars.

“Should [we] play,” he writes, “would be willing to play on the same proposition as last week - $150 for the four days and $50 for an additional day. I want to be placed in the position to play either Friday or Saturday, and for postponments [sic].”He concludes the letter with a note that “These games will draw, and will be well advertised.”

Another letter, just a week after the first, demonstrates how these teams – even ones as successful as the Giants – were still at the mercy of segregated baseball’s ownership.

“I am very sorry that the grounds are rented for all Saturdays and Sundays for the present seasons, as the date – Aug. 25-26 – had a real attraction that would have been glad to have played there.”

Later on, in “Negro Base Ball,” Foster opined how “The wild, reckless scramble under the guise of baseball is keeping us down, and we will always be the underdog until we can successfully employ the methods that have brought success to the great powers that be in baseball of the present era: organization.”

In 1920, years of frustration spurred Foster, and fellow African-American team owners, to establish the Negro National League. Foster, who had arrived at the initial meeting in February of 1920 with a charter for the league already in hand, was named president and treasurer. He continued to serve as manager and owner of the American Giants, but also ran the League with his trademark discipline and unwavering commitment to excellence.

In a letter dated Nov. 15, 1921, Foster once again communicates with Finke, but this time as a representative of the League in response to a financial dispute between the Reds and the Cuban Stars.

“Under the conditions that existed I don’t believe your company would seriously consider that the Cuban Stars owed them any deficit; when you cannot take sufficient money at the gate and have only a limited bank roll we baseball men who are strong always sympathize with the weak. Your company is too strong for such as this.”

Foster passed away just 10 years after founding the Negro Leagues, on Dec. 9, 1930.

“When Rube Foster died, Negro baseball died with him,” said fellow Negro Leagues manager and owner Joe Green.

Isabelle Minasian was the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum