- Home

- Our Stories

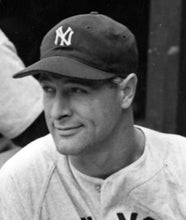

- Hall of Fame opened the day of Lou Gehrig’s final game

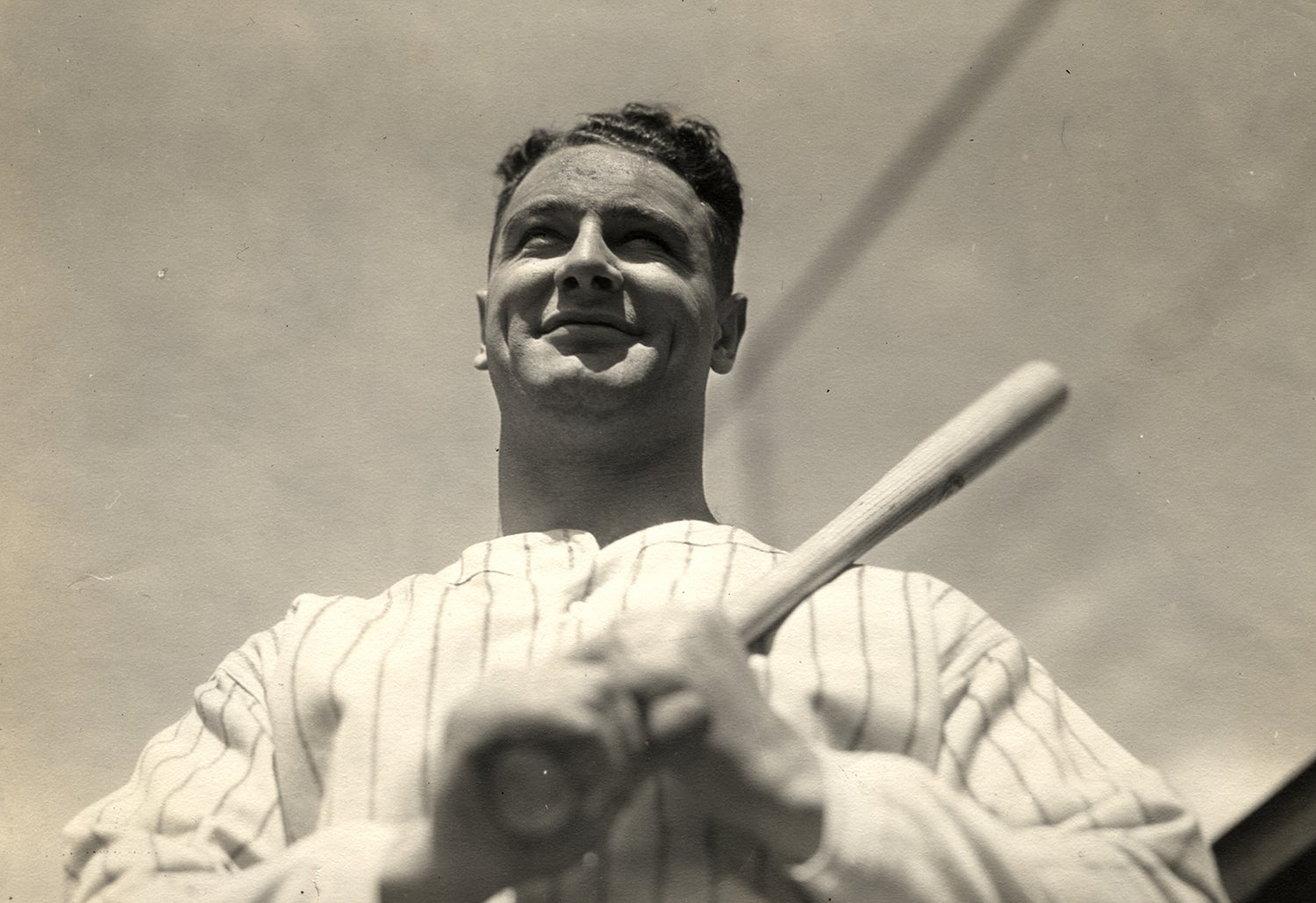

Hall of Fame opened the day of Lou Gehrig’s final game

The eyes of the baseball world gazed upon Cooperstown on June 12, 1939, as the quaint Upstate New York village hosted its first Induction Ceremony.

That same day, a thousand miles away, a future Hall of Famer would play in his final game.

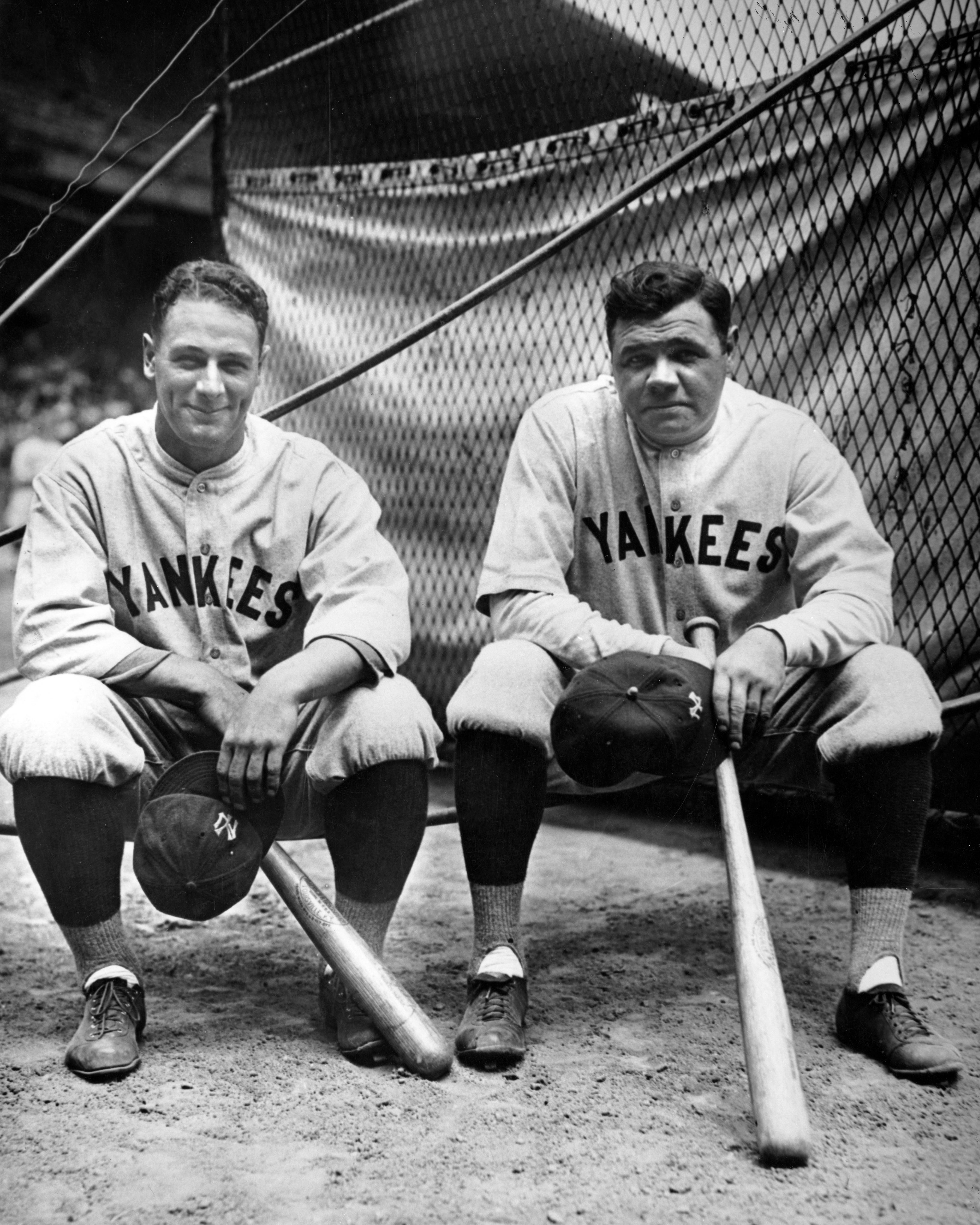

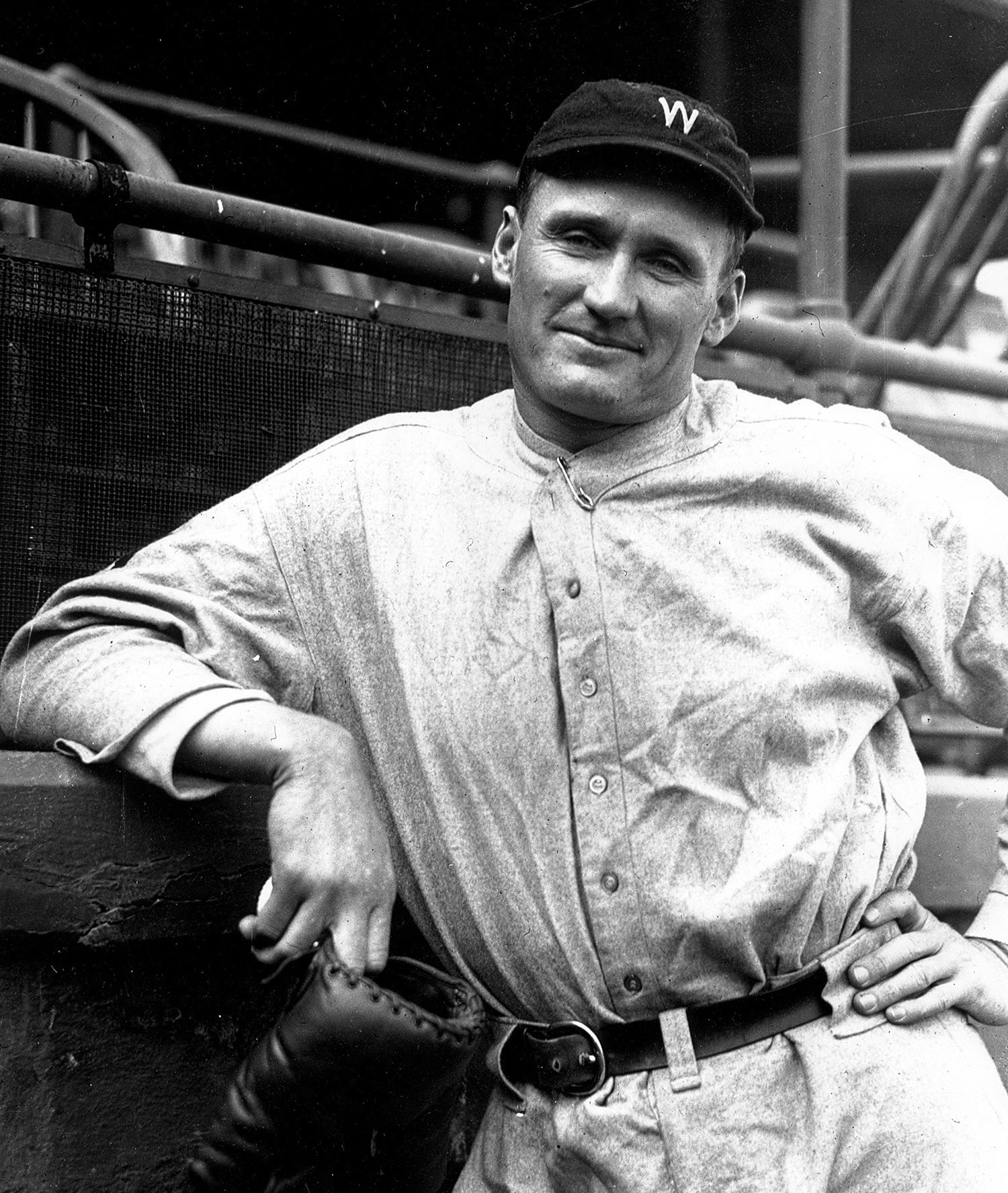

On June 12, 1939, Cooperstown was considered the baseball capital of the world. The National Baseball Hall of Fame would hold it’s first-ever Induction Ceremony that day, enshrining such living immortals as Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, Honus Wagner and Walter Johnson.

It was also on June 12, 1939, that longtime New York Yankees first baseman Lou Gehrig once again took the field.

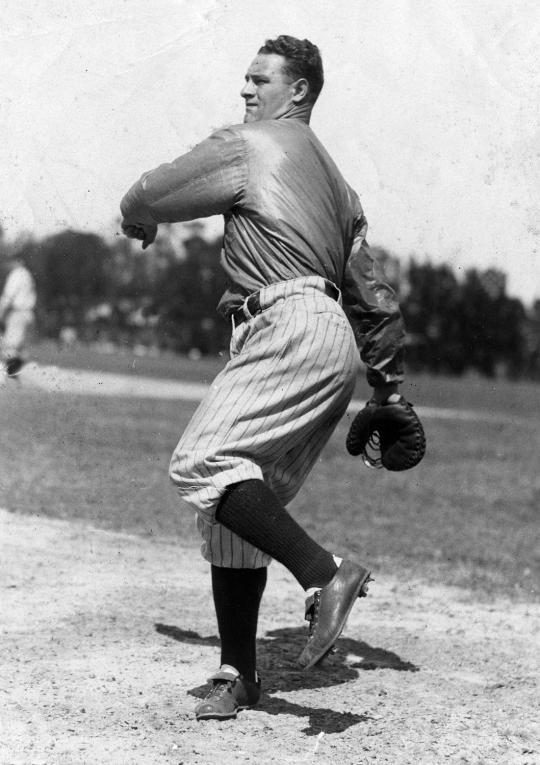

Coming off a respectable but disappointing for him 1938 campaign in which hit 29 home runs and drove in 114 but batted only .295, the first time he had hit under .300 since 1925, Gehrig was determined to return his game to its past glory. Unfortunately, when the spring of 1939 came it was plain his reflexes had slowed alarmingly.

On May 2 in Detroit, Gehrig took himself out of the lineup after a then-record 2,130 consecutive games played due to “sluggishness.” Then on June 12, 1939, was in an exhibition game at Kansas City only days before his fateful diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Gehrig appeared in an exhibition game with the Yankees in Kansas City.

“Lou never discussed his reasons for playing that day,” wrote Jonathan Eig, author of the 2005 bestseller "Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig," in an email. “When it came to expressing his feelings, he was not exactly a Hall of Famer. Or even an All-Star. But he was a ferocious competitor, and my hunch is that he missed the game, missed the action, and wanted to test himself.

“Remember, he had played a full season with symptoms of ALS in 1938. Holy cow! How did he do that? The disease was and is so difficult to understand. He didn’t feel sick. He kept thinking that he’d turn things around, that he’d bounce back, that maybe, just maybe, this thing would pass. Even for a sick man, imagine how good it must have felt to lace up the cleats, slip on the glove, and trot out onto the field one last time. Who wouldn’t do that if they could?”

The Monday contest, pitting New York against the American Association’s Kansas City Blues, a farm team of the Yankees, took place at the tail end of a western trip by the big league squad. After a series in St. Louis against the Browns, the Bronx Bombers made the short trek to Kansas City.

It was on June 10, while with the Yankees were in St. Louis, that Gehrig disclosed that he would be going to the Mayo Clinic for an examination, insisting to reporters that he expected to return as a player during the summer.

“I guess everybody wonders why I’m going,” Gehrig said to reporters. “But I can’t help believing there’s something wrong with me. It’s not conceivable that I could go to pieces so suddenly. I feel fine, feel strong and have the urge to play, but without warning this year I’ve apparently collapsed.

“I’d like to play some more and I want somebody to tell me what’s wrong. Usually a fellow slows up gradually.”

In-season exhibitions were common during this period, but having the 1939 Yankees – the defending world champions in the midst of winning four consecutive World Series titles – was a boon for baseball fans in Kansas City. The ballpark, Ruppert Stadium, had a seating capacity of approximately 17,500, but the paid attendance was announced as 23,864. Reports had fans on the roofs of the concession stands, atop telephone booths and fences in the outfield, crowded on a hill just beyond the right field fence and jammed into every aisle.

The Kansas City exhibition was won by the Yankees, 4-1, the nine-inning game taking only 1 hour and 28 minutes to play. But it was the news that Gehrig – only a week from his 36th birthday - appeared in the game that was trumpeted by newspapers across the country.

“His (Gehrig’s) appearance in the game was a surprise and done only because of the Yankees’ desire to show their appreciation of the tribute which this city paid them today,” read The New York Times the next day.

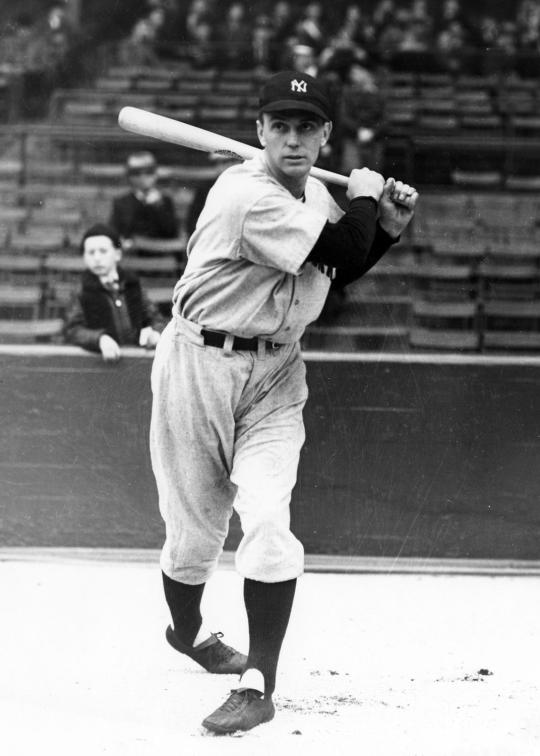

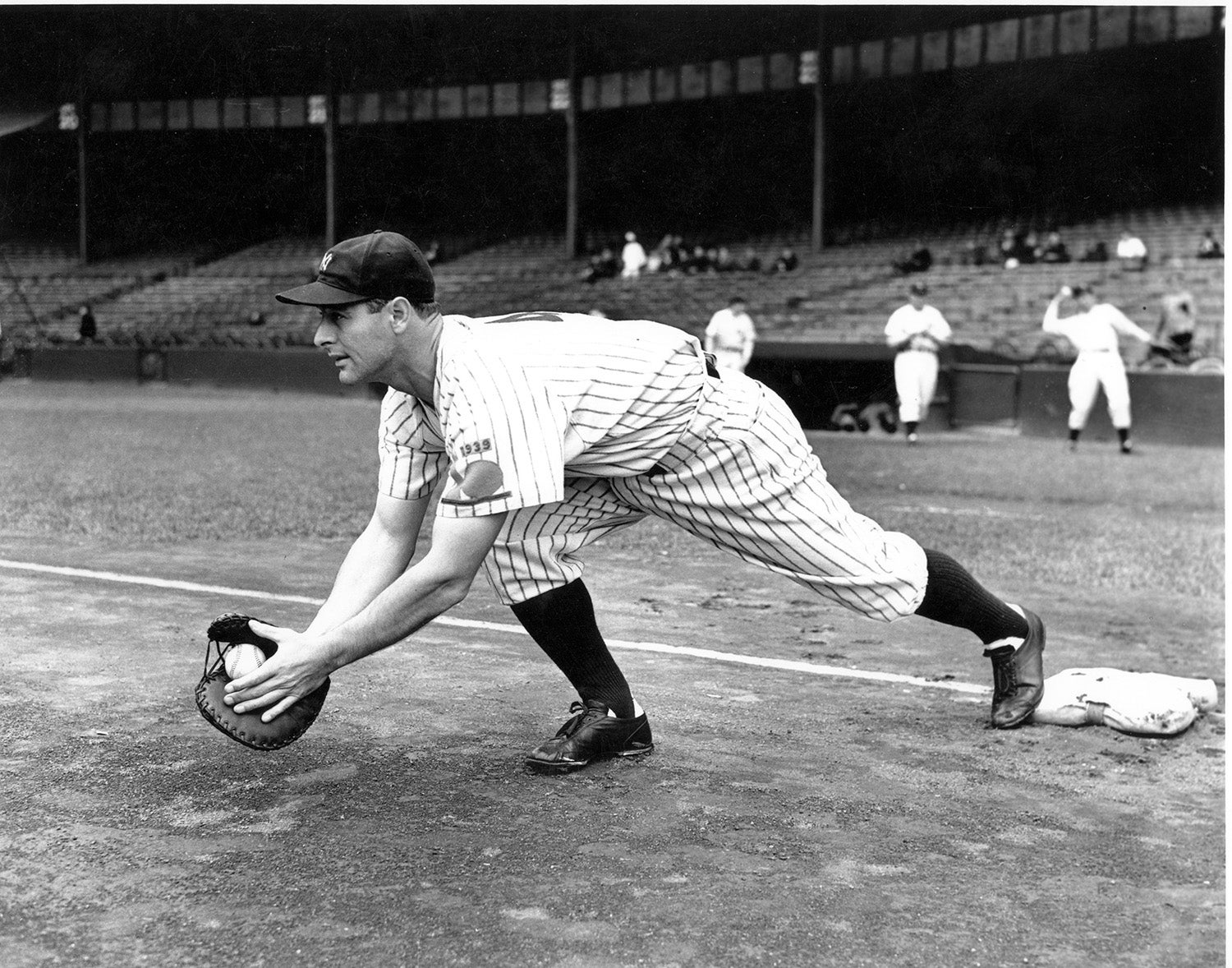

The Yankees – led by coach Art Fletcher because manager Joe McCarthy, along with players George Selkirk and Arndt Jorgens, were a part of the Cooperstown festivities –presented their regular lineup at the start of the game, names like Frank Crosetti, Tommy Henrich, Joe DiMaggio, Bill Dickey and Joe Gordon dotting field, with Gehrig manning first base and batting eighth in the lineup.

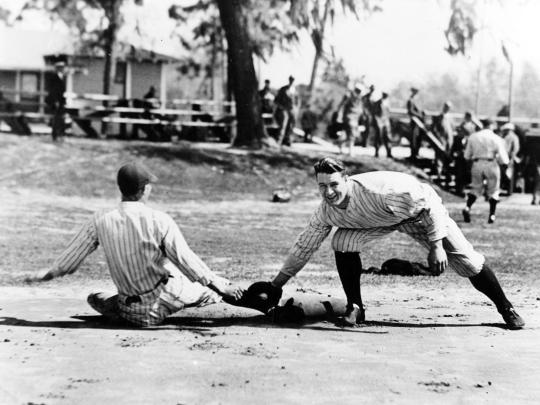

During his three innings of action, Gehrig cleanly fielded all four chances. In his only at bat, he hit the first ball pitched to him in the third inning and smacked a weak groundout to second baseman Gerald Priddy. Babe Dahlgren, who had replaced Gehrig as the first baseman the previous month when the consecutive game streak came to an end, got three hits after taking over for Gehrig against Kansas City.

While the rest of the Yankees left on a train for New York after the game, spending two nights aboard the Pullman before opening a home stand against the Indians, Gehrig was headed for the famed Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., for a complete physical examination.

Gehrig attempted to travel incognito from Kansas City to Rochester, Minn. – flying under the name of “Lorenz” – but was recognized during a stopover at the Minneapolis airport, including by a small group of camera-toting youngsters whom he later bought a round of hot dogs for.

During the two-hour layover in Minneapolis, Gehrig told reporters he felt all right, expected to return to the Yankees lineup and had been assured if there’s anything wrong “they will find out at Rochester. I need that old speed back and that’s why I’m going to have a checkup.

“I don’t know if I’ll ever get back in the harness or not. It all depends on what they find down there. I can only hope.”

After being examined by Mayo Clinic physicians from June 13-19, 1939, Gehrig returned to New York, where he presented the medical institution’s report to McCarthy and Yankees President Ed Barrow at Yankee Stadium on June 21. After a conference in McCarthy’s office, Barrow read the report from Dr. Harold Hobein to an anxious media throng.

“After a careful and complete examination it was found that he is suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,” the statement read in part. “This type of illness involves the motor pathways and cells of the central nervous system and in lay terms is known as a form of chronic poliomyelitis – infantile paralysis.

“The nature of this trouble makes it such that Mr. Gehrig will be unable to continue his active participation as a baseball player inasmuch as it is advisable that he conserve his muscular energy. He could, however, continue in some executive activity.”

For the once strapping physical specimen, the broken bones, concussions, lumbago, bumps and bruises he had to endure to continue his remarkable streak were minor inconveniences compared to the effects of ALS.

“What my physical examination revealed came as a distinct shock to Mrs. Gehrig and myself,” Gehrig said. “Before I went to the clinic I made a thousand guesses as to what might be the matter with me. What the tests showed was the one thing I never suspected. Mrs. Gehrig and I are fully resolved to face the situation calmly.

“It’s something to know what was wrong with me. I was sure that there must be some unrevealed reason why a man in such good general health as I enjoy should suddenly lose the coordination needed for playing baseball. Going to the Mayo Clinic was the best move I ever made.”

Gehrig even joked about the many physical examinations he underwent at the Mayo Clinic. “They even made an x-ray picture of my head,” he said, before adding with a grin, “but they didn’t find anything there.”

Despite his brave public face, Gehrig was also realistic about his future.

“My friends tell me not to worry,” he said. “They slap me on the back and say, ‘Don’t worry, Lou. Everything is going to be all right.’ But how can I help worrying?”

Later that summer, on July 4, 1939, Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day was held at Yankee Stadium, where Gehrig uttered the now famous and poignant words at a home plate ceremony: “Fans, for the past two weeks you have been reading about a bad break I got. Yet today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth.”

On Dec. 7, 1939, the BBWAA voted unanimously to suspend the waiting period and placed Gehrig in the Baseball Hall of Fame immediately “to commemorate the year in which he achieved his record.”

Less than two years later, Gehrig died at the age of 37 on June 2, 1941.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum