- Home

- Our Stories

- GI World Series of 1945 featured diverse heroes of the diamond

GI World Series of 1945 featured diverse heroes of the diamond

Sunday afternoon, Sept. 2, 1945, resembled any other at the ballpark: Sunshine splashed across green grass, fans drinking beer, live radio broadcast, the Stars and Stripes fluttering from the flagpole.

The ballpark, however, was anything but conventional.

This game was played at Stadion der Hitlerjugend, the Hitler Youth Stadium in Nuremberg. Here, Adolph Hitler had delivered his incendiary antisemitic speeches at the Nazi rallies.

Now, four months after Germany's surrender and Hitler's death, American troops had painted over the swastikas, laid out a baseball diamond and transformed the Fuhrer's platform for bigotry into a showcase of democratic ideals.

Baseball had swept through Europe that summer with the advance of American troops and the defeat of the Axis powers. Each military branch and its different divisions had their own teams. All told, more than 200,000 American servicemen played baseball across the continent, which culminated in the European Theater of Operations championship, better known as the GI World Series.

A month before the Detroit Tigers would play the Chicago Cubs in the Fall Classic back home, the Overseas Invasion Service Expedition (OISE) All-Stars based in France took on the heavily favored "Red Circlers" (so named for the patch on their uniform shoulders) representing the 71st Division of General George Patton’s Third Army occupying Germany.

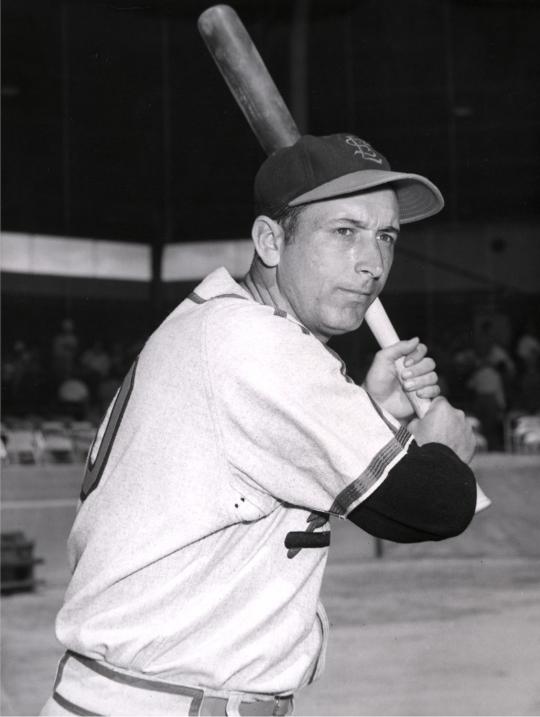

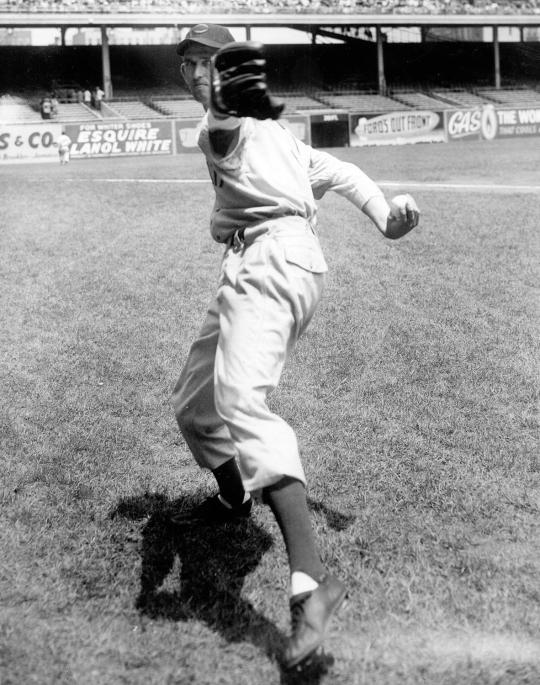

The St. Louis Cardinals' peacetime center fielder, Private First-Class "Harry the Hat" Walker (from his habit of adjusting his cap between pitches), had received a Bronze Star and Purple Heart for his wartime work as a reconnaissance scout. He also served as head of Germany's baseball operations. There, he had assembled a team for the playoffs from other units that included nine major leaguers on his 20-man roster. They included Cincinnati Reds' pitcher Ewell Blackwell, who had gone undefeated and thrown a no-hitter in the playoffs leading up to the GI Series, and big league outfielders Johnny Wyrostek and Maurice Van Robays.

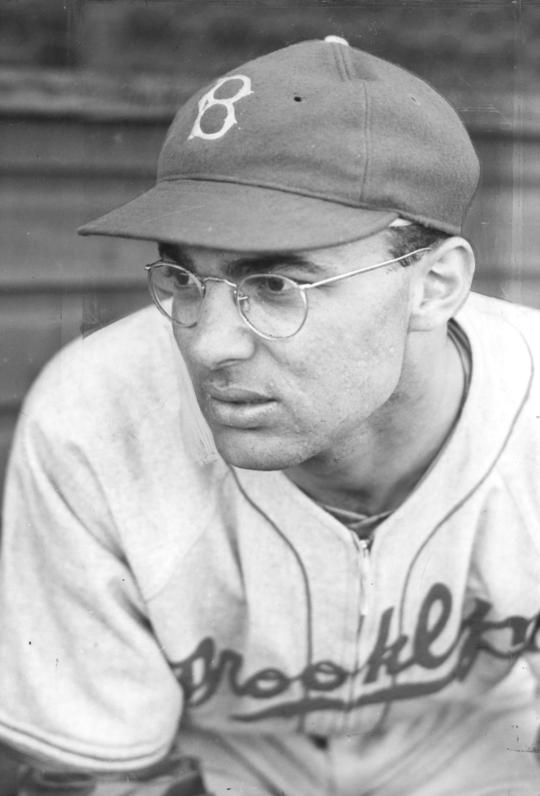

Walker's nemesis in the opposite dugout for the championship was player/manager Staff Sergeant Sam Nahem, who had pitched three seasons in the big leagues – one with the Cardinals, one with the Phillies – before enlisting in the fall of 1942. Nahem had spent two years stateside before being sent overseas in late 1944, serving with an anti-aircraft artillery unit. Born to Syrian immigrants in a Jewish enclave of Brooklyn, Nahem had quit college when Casey Stengel signed him to play in the Dodgers' organization, finishing his undergraduate studies and then law school during the off-seasons and passing the bar in New York. His eyeglasses bolstered his image as an intellectual, and so did quotes from Shakespeare and Maupassant he dropped in casual conversations.

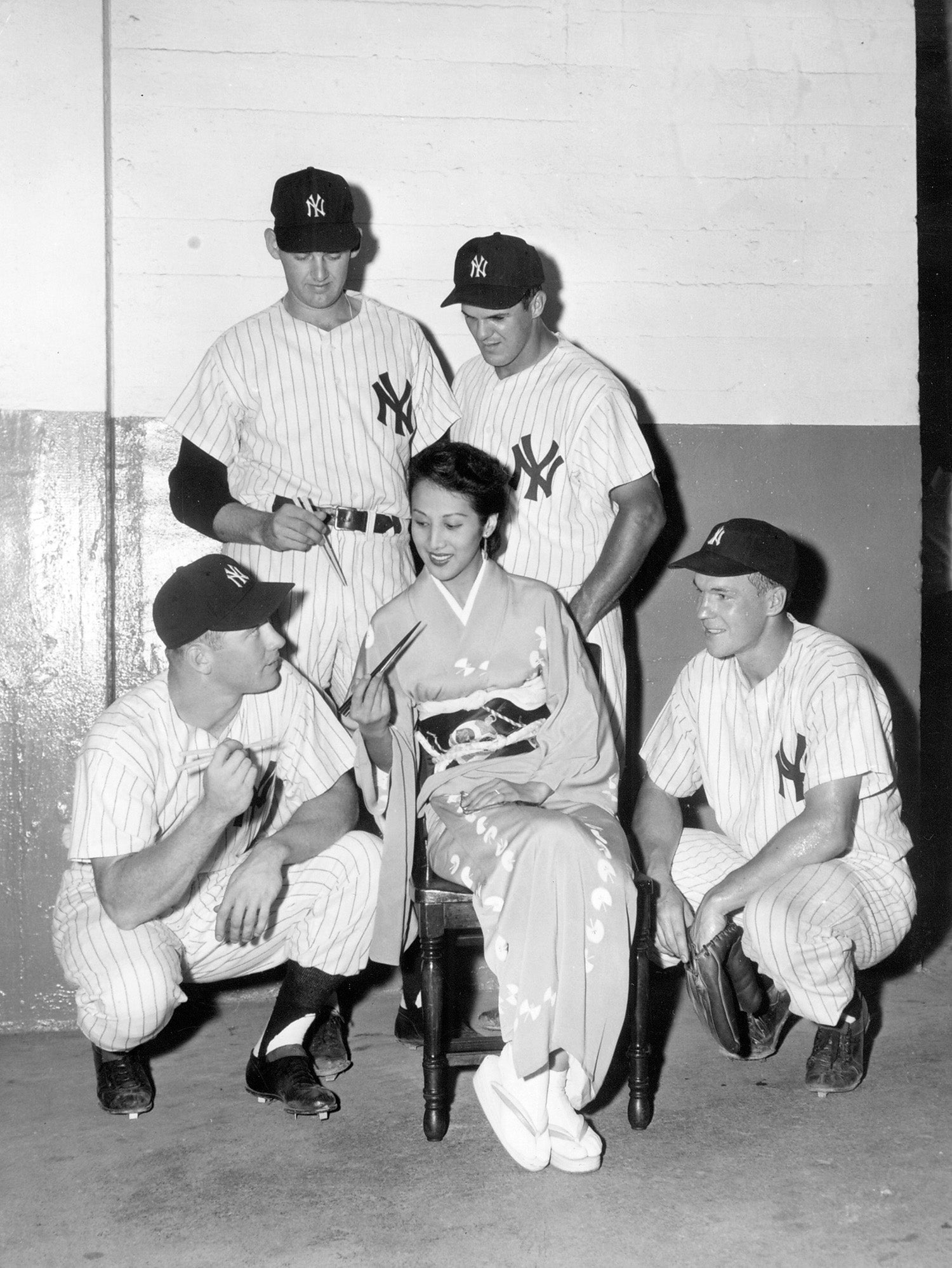

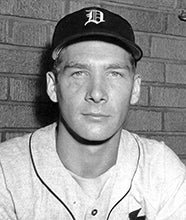

Harry Walker, who hit .294 in 1943 as the center fielder for the NL-champion St. Louis Cardinals, received a Bronze Star and Purple Heart while serving in World War II. During his time in the military, Walker assembled a team that would play in the 1945 GI World Series. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

At 6-foot-1 and 190 pounds, Nahem had physical size to match his intellect. But he had lacked the resources to assemble a team equal to Walker's, fielding a collection of semipro and minor league players, plus one other major leaguer, Russ Bauers, a right-handed pitcher with a 29-29 record for the Pirates from 1936-41. Nahem's best off-field move proved to be adding two Negro League stars at a time when the military's stark racial divisions prevented servicemen like Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby from playing baseball at their U.S. bases.

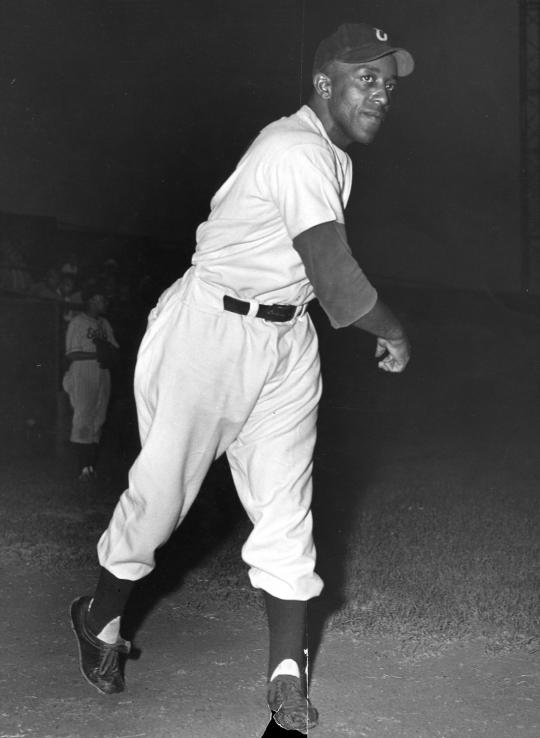

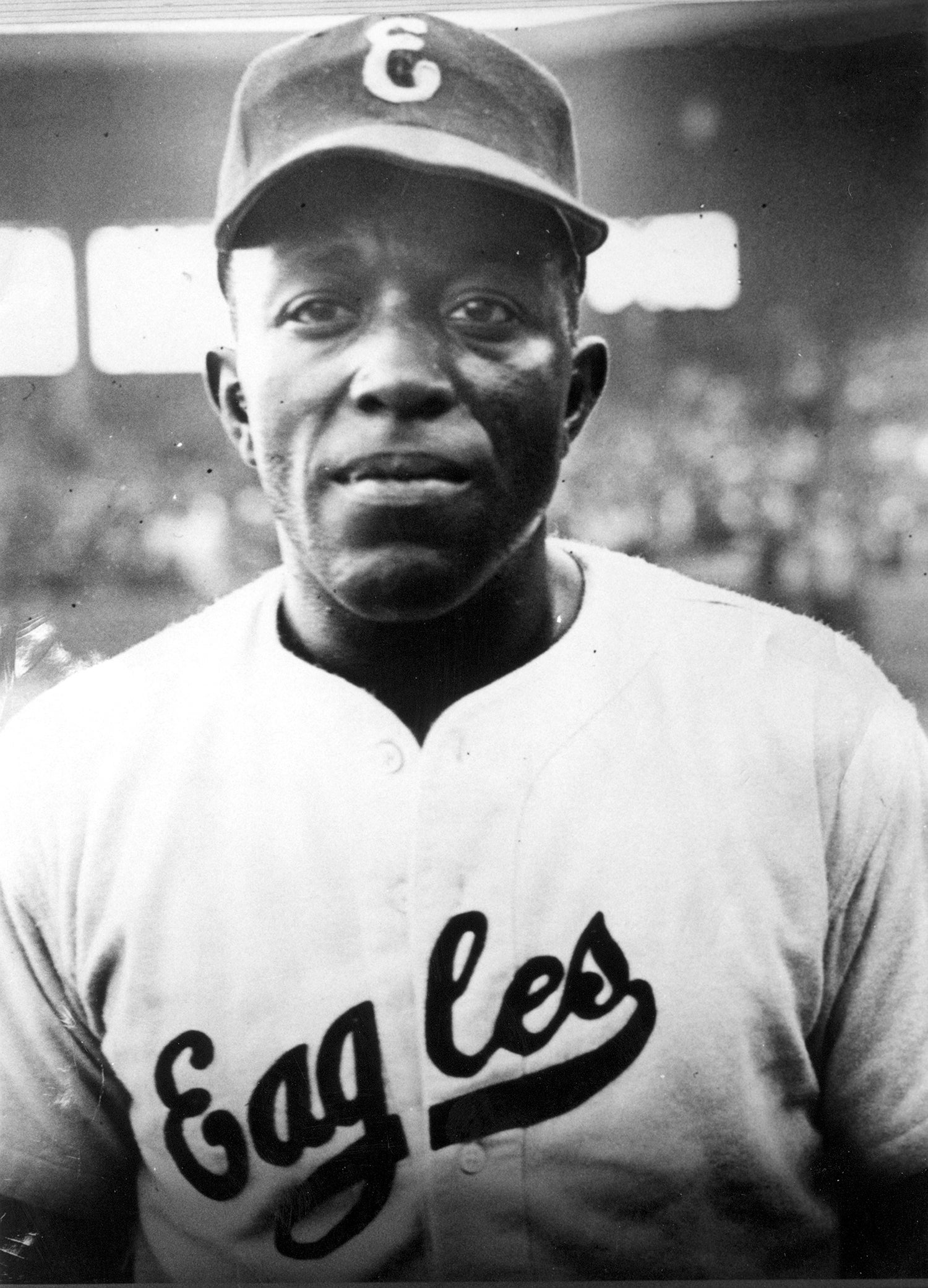

In the 1930s, Nahem had joined the communist party, which advocated for the abolition of Jim Crow and the integration of organized baseball. He integrated his OISE team with pitcher Leon Day of the Newark Eagles and the 818th Amphibian Battalion, a segregated unit. Day had driven a "duck," an amphibious vehicle, to deliver supplies on Utah Beach six days after D-Day, and outdueled Satchel Paige in the 1942 Negro League East-West All-Star Game.

Nahem’s other key addition was power-hitting outfielder Willard Brown of the Kansas City Monarchs, whom Josh Gibson had nicknamed "Home Run Brown." Brown had entered the U.S. Army in 1944 and done his part in the D-Day invasion by hauling ammunition and guarding prisoners.

Sam Nahem spent parts of four seasons in the big leagues. A stint in the U.S. Army during World War II interrupted his pitching career, but while serving in the military Nahem helped assemble a diverse team – featuring Negro League stars Willard Brown and Leon Day – that would win the 1945 GI World Series. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

The first game of the series, played that sunny Sunday afternoon in the Nuremberg stadium before 50,000 fans – easily the largest baseball crowd in Europe during the war – exposed the discrepancies between the two teams. Ewell "The Whip" Blackwell baffled the OISE batters with his sidearm, buggy whip delivery, striking out nine, while Nahem's fielders made seven errors behind him, and the Red Circlers waltzed to a 9-2 victory.

But the following afternoon, Leon Day – able to mix a biting curveball with 95 mph fastballs using his signature no windup, short-arm delivery – evened the series with an even more dominating performance than Blackwell's: Striking out one more than "The Whip" (10 total) and allowing one less hit (four). Nahem, playing first base, produced two hits and drove in the winning run in the 2-1 triumph.

With the Series tied at one apiece, the two teams traveled to Reims, France, to play the next two games at Headquarters Command Athletic Field. On Sept. 6, Nahem and Blackwell went at it again. Nahem had learned a slider from Burleigh Grimes, his manager in Montreal in 1939, which he used effectively. He also threw overhand to left-handed batters and sidearm to righties, which worked that day. Nahem allowed only four hits, one more than Blackwell, but his team prevailed in the runs column, winning 2-1 and giving the underdogs the Series lead.

In Game 4 the next afternoon, Day could not repeat his magic of his previous start and was beaten 5-0. Walker hit a two-run home run while Day's team managed only five singles.

The decisive Game 5 was back in Nuremberg on Sept. 8. Once again, Blackwell and Nahem took the mound for their respective teams. The Red Circlers took an early 1-0 lead. In the fourth inning with only one out, they loaded the bases. Nahem replaced himself on the mound with Bobby Keane and moved to first base. Keane retired the first two batters he faced to work out of the jam.

The Red Circlers tied the game in the sixth. In a dramatic bottom of the ninth inning, Nahem's team managed to push another run across the plate to seal a 2-1 win and the '45 GI World Series victory.

Brigadier General Charles Thrasher honored the team back in France with a parade and a steak and champagne banquet. Robert Weintraub, who describes the moment in his book "The Victory Season," notes: “Day and Brown, who would not be allowed to eat with their teammates in many major-league towns, celebrated alongside their fellow soldiers."

After the War, Nahem played on the weekends for a couple of years with the semipro Brooklyn Bushwicks and worked as a law clerk before the Phillies summoned him to pitch in 1948, mostly in relief. Nahem then played another season with the Bushwicks and briefly in Puerto Rico before retiring. He found work with a fertilizer plant in California. Disillusioned by Russia, he left the communist party in 1957 but remained a social activist and union member for 25 years in his second career.

Brown returned to the Monarchs in 1946 and had one of his best seasons.

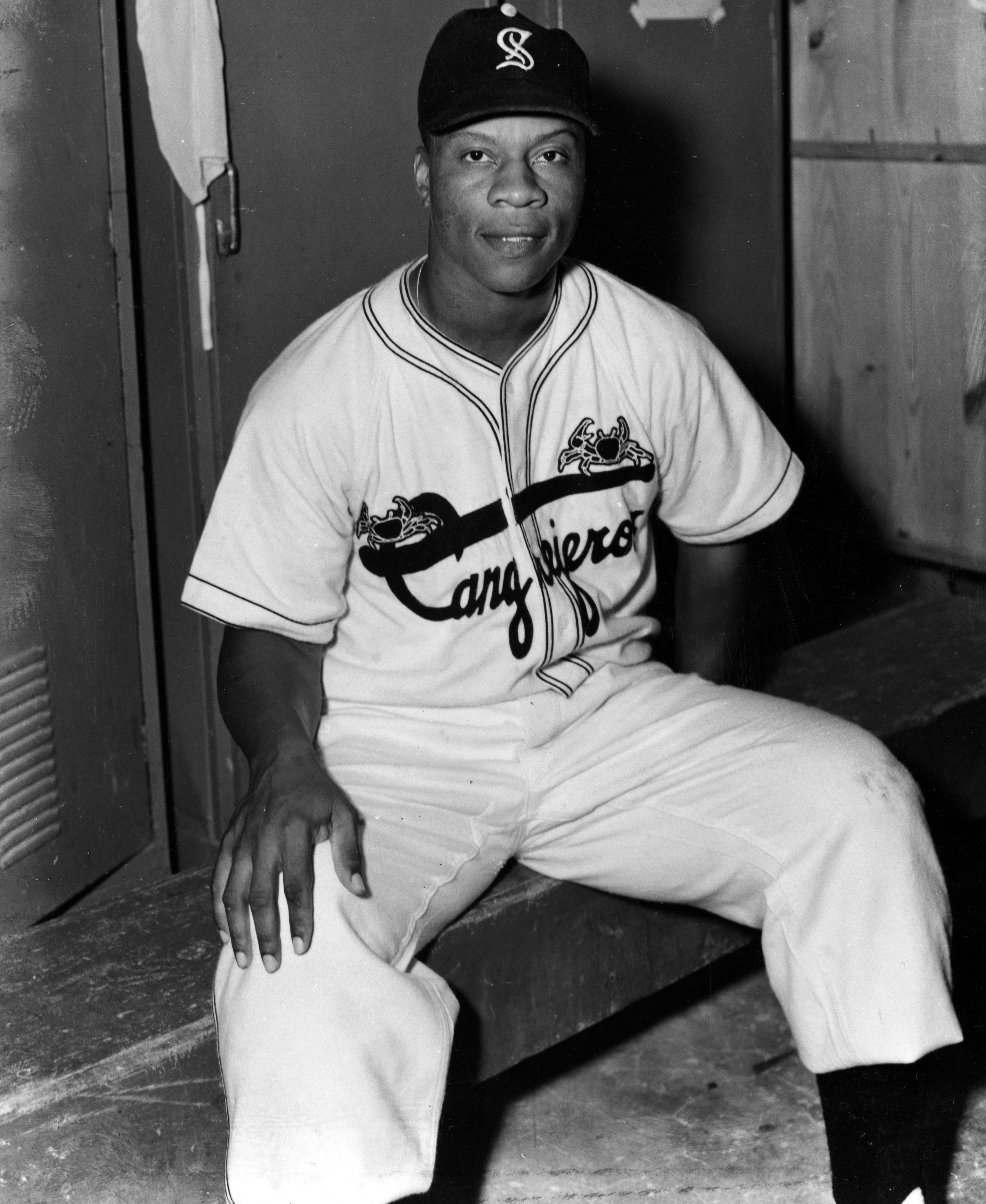

The St. Louis Browns signed him midway through the 1947 season. He became the first African American to hit a home run in the American League – a pinch-hit, inside-the-parker off Hal Newhouser – but the Browns released him after a month. He played two more seasons with the Monarchs and several for the Santurce Cangrejeros (Crabbers) in the Puerto Rican Winter League, winning its Triple Crown twice. He was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006.

There's a story – unconfirmed – that Jackie Robinson tried to convince Day to play with him in Montreal, where they would integrate organized baseball together in 1946, but Day opted instead to return to his old team in Newark. He pitched a no-hitter on Opening Day and helped his team win the Negro League World Series. Despite arm trouble, he pitched several more seasons in the Caribbean and the minor leagues before having to retire. On March 8, 1995 – six days before his death from complications of diabetes and heart trouble – Day took a call in his hospital bed informing him that he had been elected to the Hall of Fame.

"I'm so happy, I don't know what to do," he said. "I never thought it would come."

Each one of these men had their moments of glory elsewhere, but it was united as teammates during the '45 GI World Series – and in particular their combined heroics in Game 5 – that two African Americans and the Jewish manager/pitcher/first basemen staged an upset not only of their opponents on the field but of the Nuremberg stadium's legacy in an extraordinary exhibition of equality.

John Rosengren is a freelance writer from Minneapolis