- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: Asian Games

#GoingDeep: Asian Games

After being away for three months in with a team of big leaguers spreading the gospel of baseball in Asia, Herb Pennock arrived stateside via the SS Korea Maru to Pier No. 34 in San Francisco on Jan. 31, 1923, to career-altering news.

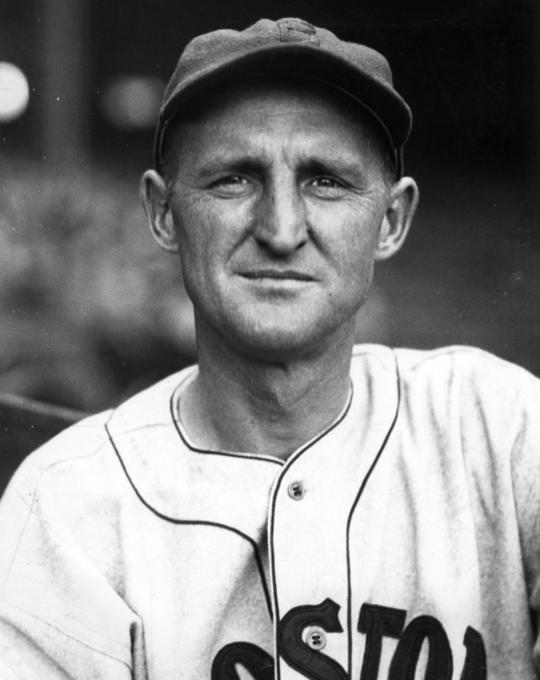

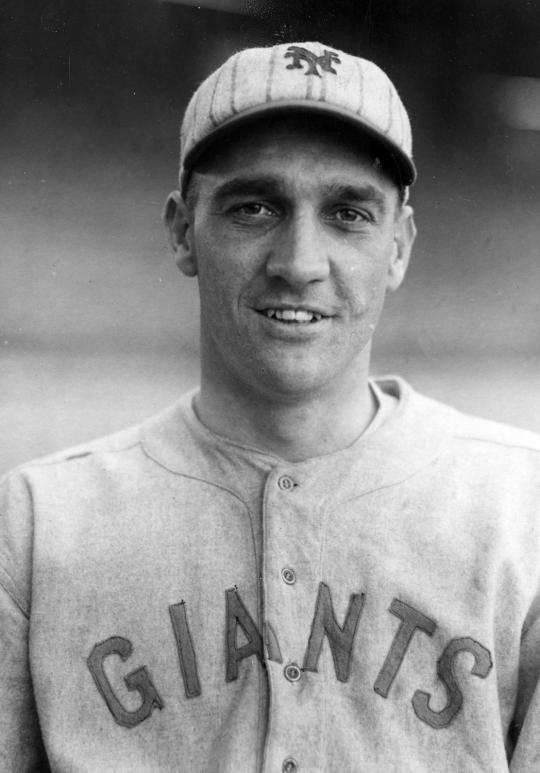

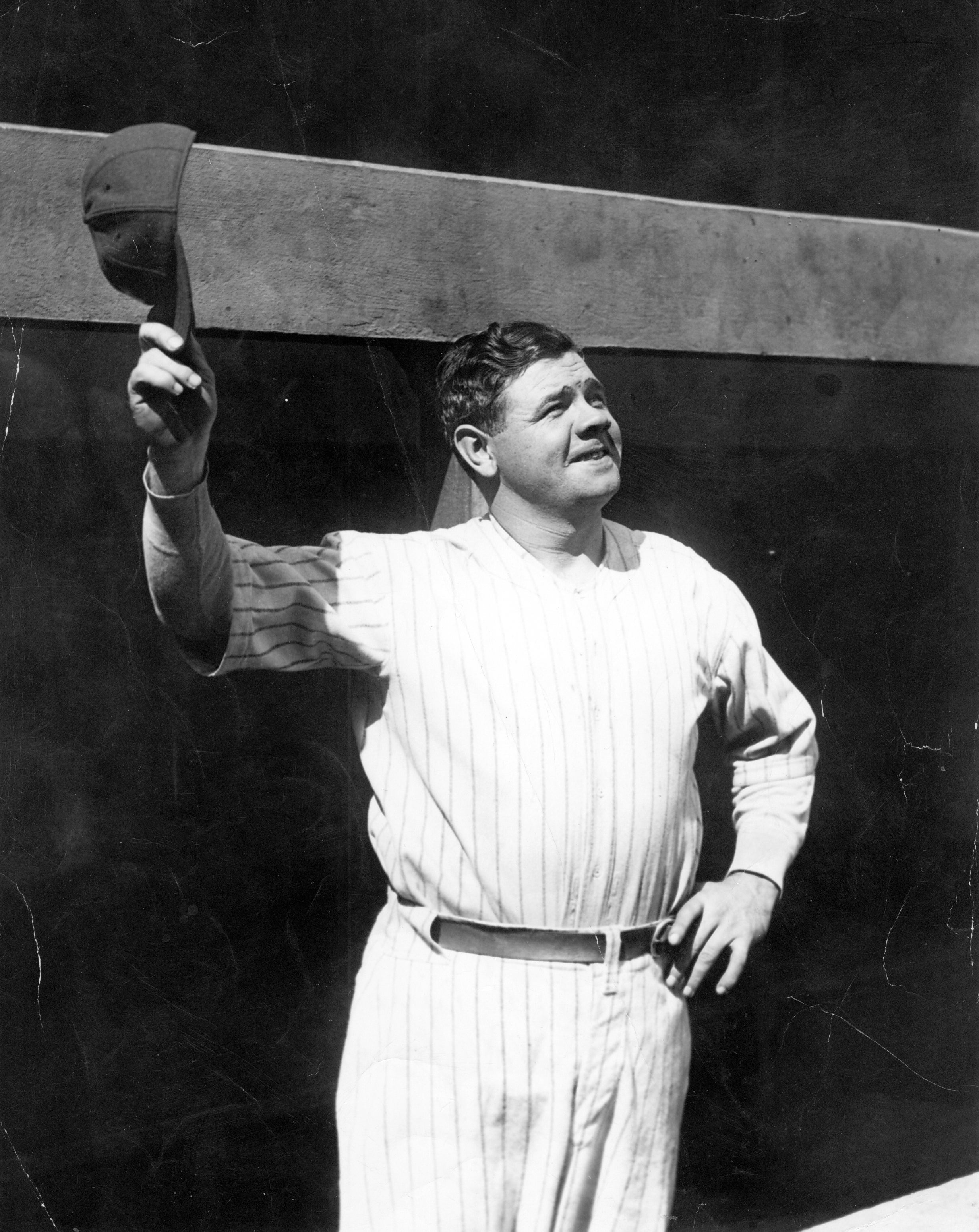

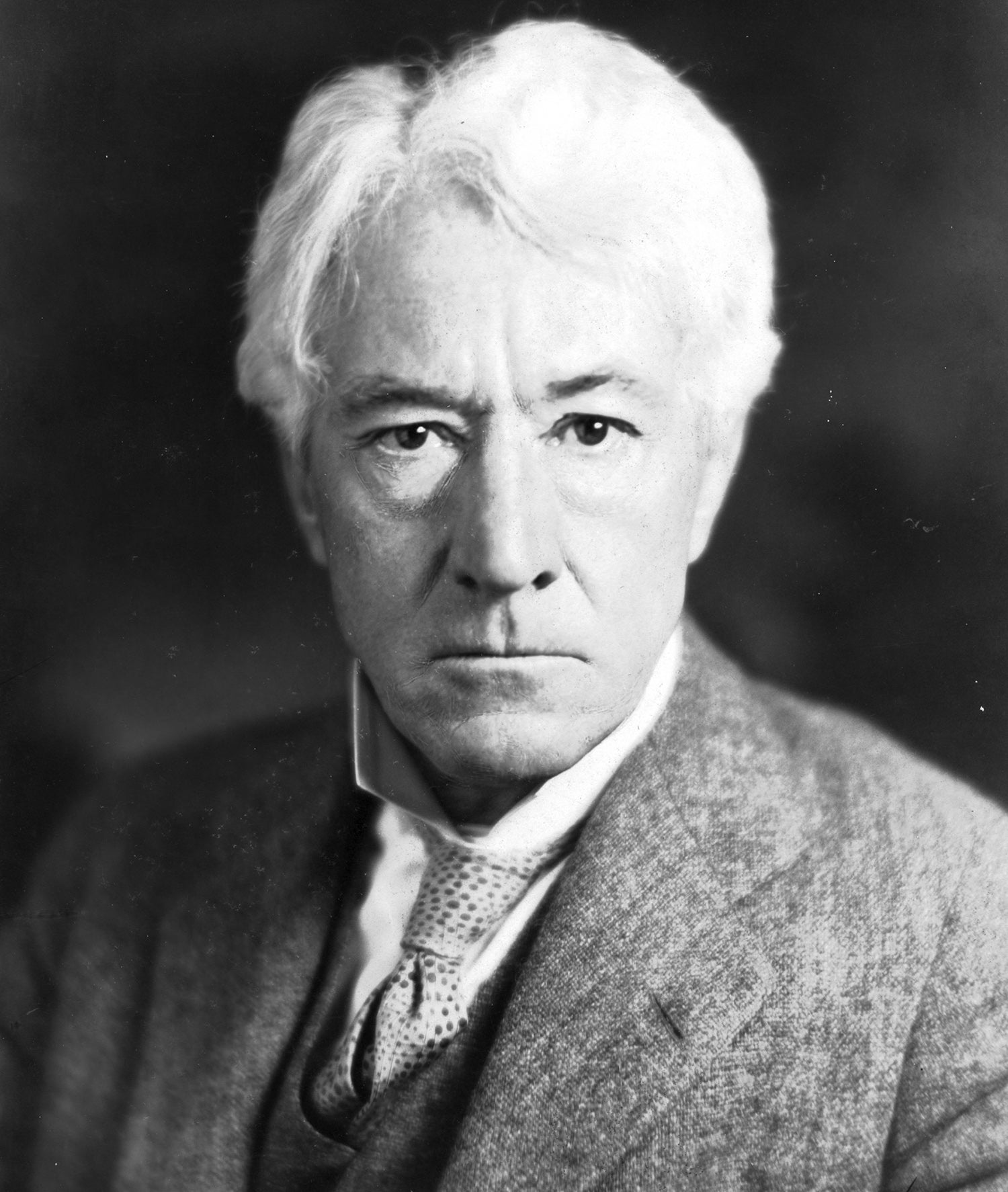

The southpaw hurler spent his first 10 big league seasons, from 1912 to 1922, toiling unremarkably with the Philadelphia Athletics and Boston Red Sox, compiling a 77-72 record and 3.72 ERA. But now he was presented with the surprising information he had been traded to the New York Yankees, the defending American League pennant winners. This transaction and its subsequent career trajectory would help the Squire of Kennett Square with a bronze plaque in Cooperstown.

“I did not know of my trade to the Yanks until our ship was about to pass through the Golden Gate. Bill Lange (a New York Giants scout based in San Francisco who was a big league star in the 1890s) gave the information to the pilot and when he came aboard he told me the good news,” Pennock told a reporter. “I hardly believed it at first, as some of the members of the party circulated all sorts of stories of fake deals. Irish Meusel had everybody on the team swapped somewhere else, saying that the Marconi operator received it by wireless. So I thought I was only being kidded, but soon there came the realization that it was the truth. Then my joy knew no bounds. My wife and I fairly danced around the deck in delight and all the players showered us with congratulations.”

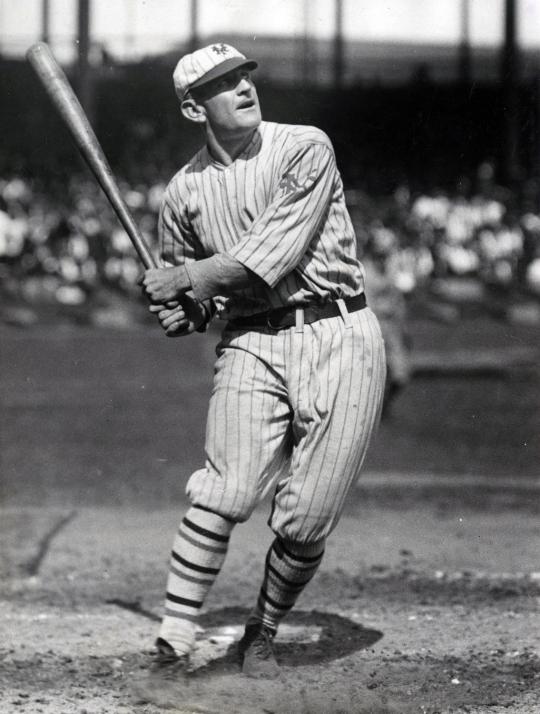

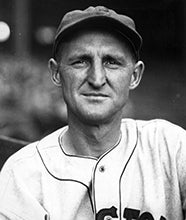

The 1922 Red Sox finished last in the eight-team Junior Circuit, their 61-93 record 33 games behind the first-place Yankees. Pennock, a reliable portsider, won 10 of 27 decisions, the 28-year-old starting 26 of 32 games while ending the season with a 4.32 ERA. He’d be joining a team with an abundance of former Red Sox players, including fellow hurlers Waite Hoyt, Joe Bush, Carl Mays, Sam Jones, Dutch Leonard and Ernie Shore, as well as Babe Ruth, Wally Schang, Joe Dugan and Everett Scott.

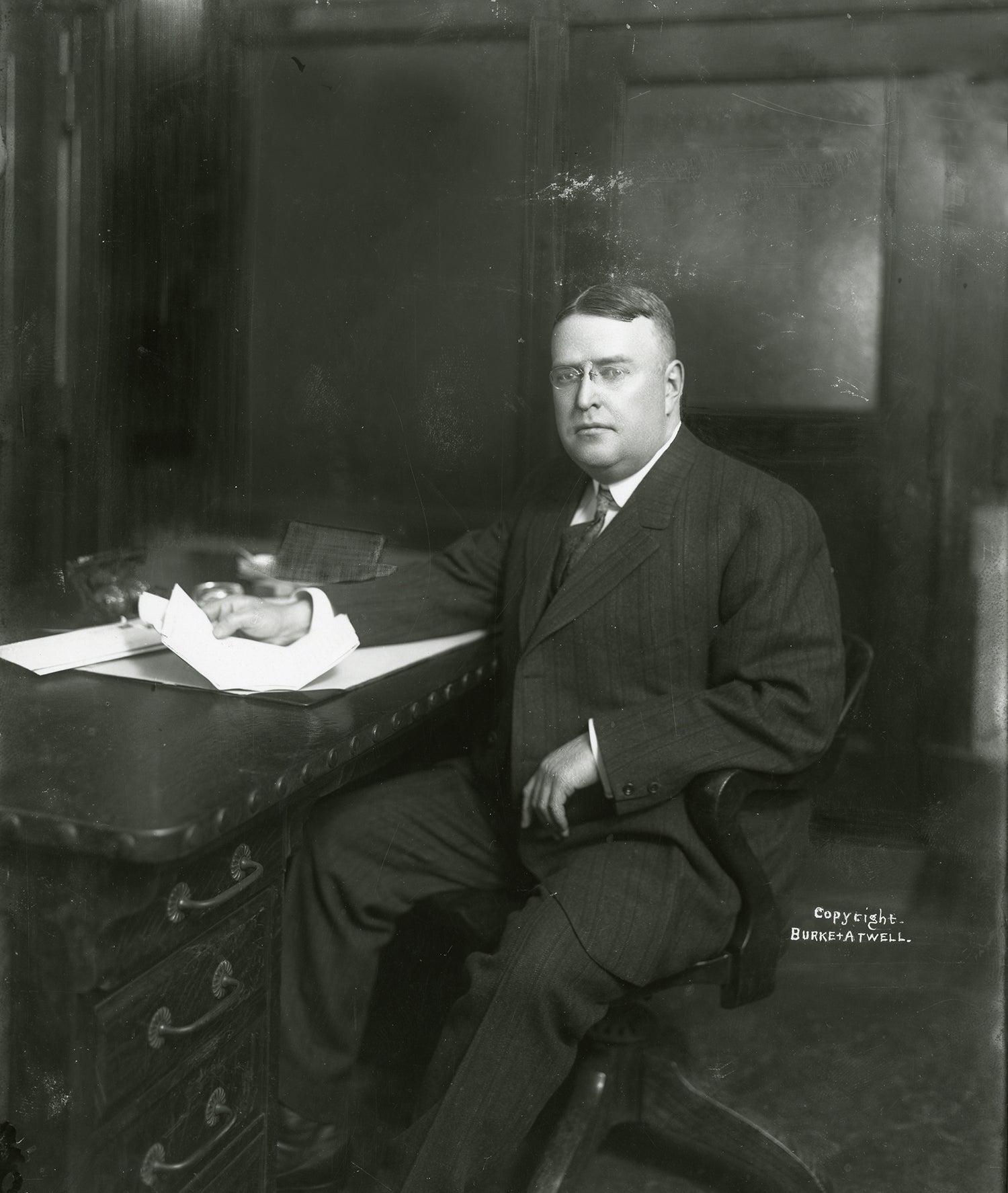

“It means something to go with a team that is a pennant contender. I was beginning to tire very much of the Red Sox, but I would like to say here that Harry Frazee, the Red Sox president, always treated me fairly. I think he is a much misunderstood man,” Pennock said. “Of course, I have a new incentive and will throw my arm off to win for the Yankees. I was very pleased to read Connie Mack’s flattering story that he expected me to be the leading southpaw in the American League next season. I certainly am going to try to get that rating.”

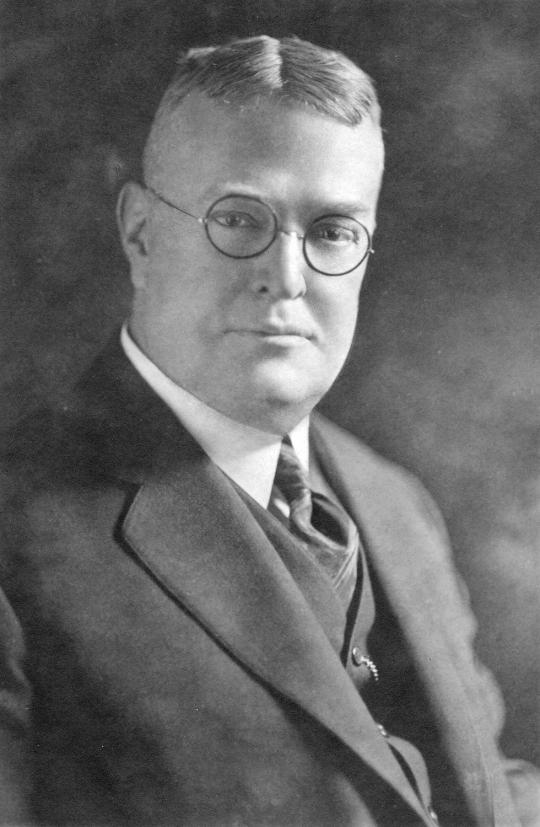

New York acquired Pennock in exchange for $50,000 and three young players – pitcher George Murray, infielder Norman McMillan and outfielder Camp Skinner – who ultimately didn’t prove successful in Boston. But when the trade was announced, Frazee was convinced his team came out on top.

“Personally, I think it’s the smartest trade that has been made since I have been associated with the American League,” said Frazee, the man who had sold Babe Ruth to the Yankees three years earlier. “I think that the future will bear out my prediction that in George Murray alone we got full value for Pennock.”

Murray, a right-handed pitcher, would go on to win nine games over two seasons with Boston, finishing with a career record of 19-26.

Almost a decade later, Pennock’s wife, Esther, who had accompanied her husband on the goodwill tour of Asia, recalled their reaction to the unexpected trade to the Yankees in the August 1933 issue of Good Housekeeping magazine.

“I believe the biggest thrill I ever had in my life was the time I learned Herb had been traded to the Yankees,” she said. “We had been through the Orient with a picked team, playing exhibition games in Japan and China. That was in 1922-23, when Herb was with the Boston Red Sox. There had been some talk about new men for the Yankees, but everyone said the one thing the Yankees did not need was pitchers. The day we landed in San Francisco a friend met us at the boat with a newspaper that told of Herb’s being traded, and we really danced a jig. New York was our goal, and we had finally made it.”

Pennock spent the next 11 seasons pitching for a Yankees team that would capture five AL pennants and four World Series crowns. His career record during this successful era in franchise history was 162-90, which included two 20-win seasons and eight campaigns with at least 11 wins. His 241 career triumphs during his 22 major league seasons led to election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1948.

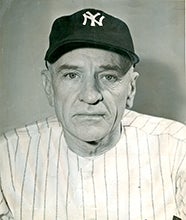

In 2022, a jersey Pennock wore during the 1922-23 Herb Hunter All-Americans tour that included stops in Japan, Korea, China, Manila and Hawaii was donated to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Other ballplayers on the trek included future Hall of Famers Casey Stengel, Waite Hoyt and George “High Pockets” Kelly, as well as Bullet Joe Bush, Bibb Falk, Riggs Stephenson and Luke Sewell.

“I donated the Herb Pennock jersey because I believe in everything that the Hall of Fame stands for in terms of protecting the game and educating people as to the past and making a bridge to the present and even the future. It's just important. The Hall of Fame is an important institution,” said donor Dr. William Sear, a Georgia resident whose collection specializes on overseas tours. He acquired the Pennock jersey via auction approximately 20 years ago.

Pennock’s cream-colored uniform shirt has seven white buttons down the front placket, with the left sleeve sporting a red, white and blue embroidered shield-shaped patch with a Japanese flag in the center.

“The Hall of Fame is fortunate to have quite a few artifacts from historic overseas baseball tours from as early as 1874 to the modern day, but our collection has very few objects from the 1922-1923 Herb Hunter All-Americans tour of the Far East,” said Hall of Fame senior curator Tom Shieber. “This Herb Pennock jersey is a remarkable addition to our collection that helps us tell the important story of this and many other tours that helped spread goodwill and the game of baseball around the world.”

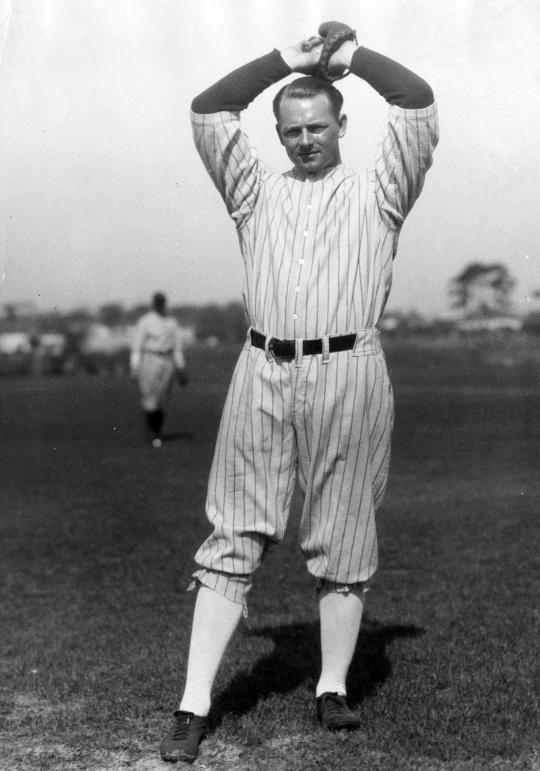

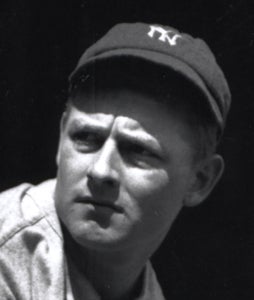

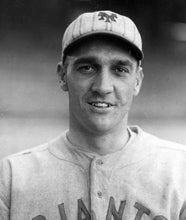

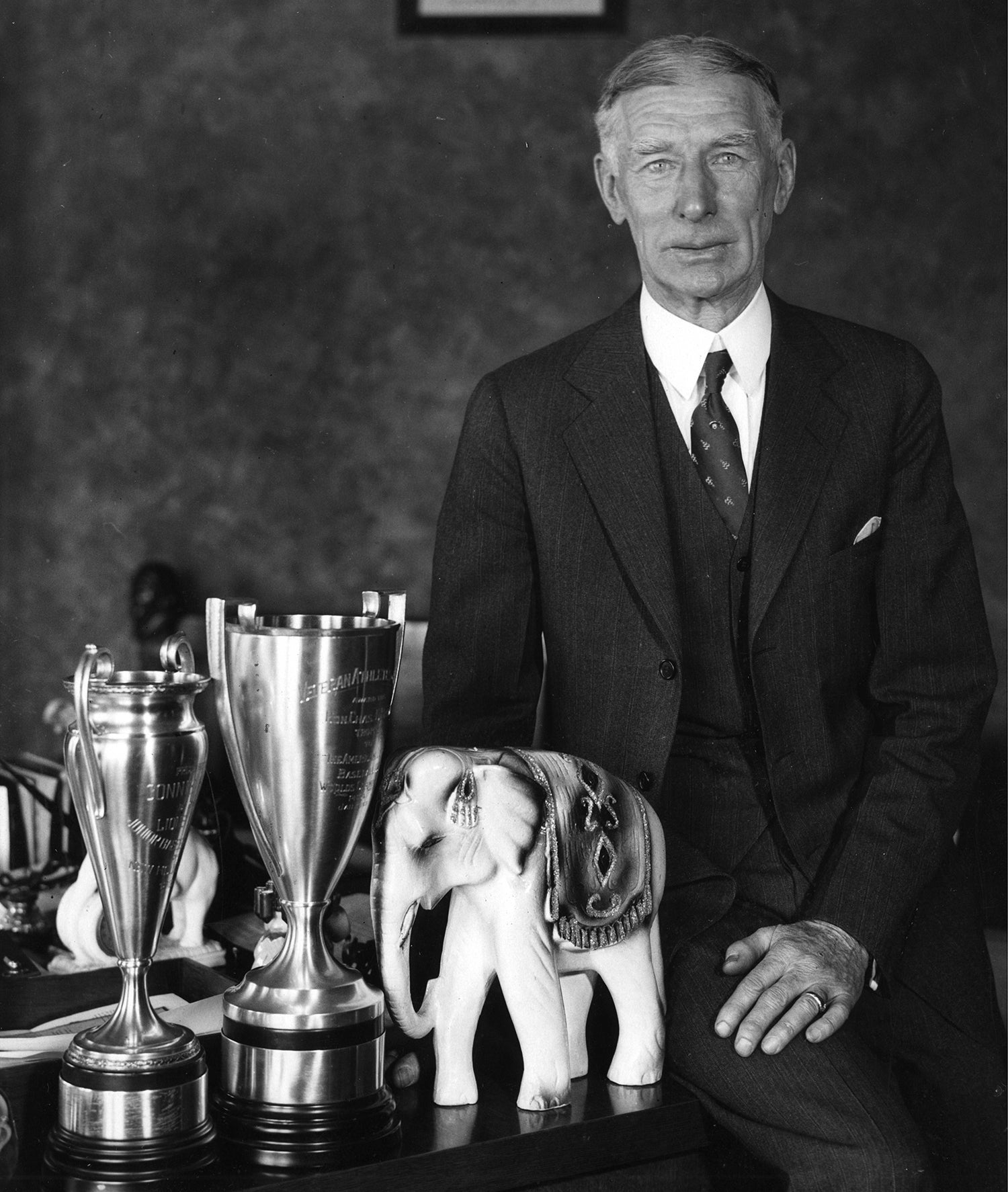

The 1922-23 offseason tour was the brainchild of the aforementioned Herb Hunter, a former big league utilityman with cups of coffee with the Giants, Cubs, Red Sox and Cardinals for four seasons between 1916 and 1921. Having been on a ballplaying tour of Japan in 1920, and coaching baseball at both Waseda and Keio Universities in Japan, the man later to known as “Baseball’s Ambassador to the Orient” took on the role of organizing the overseas excursion.

“If baseball continues to advance with its present stride in Japan, I believe that we will be playing an annual international series before long,” Hunter told a reporter in May 1922. “The Japanese boys do not equal our major league stars in ability, but several members of the Waseda team could make good in the minor leagues. Interest in baseball increases every year and I find that the higher class of people are taking to it. However, boys from all classes play their own little corner-lot games.”

Hunter’s plans for selection of players for this particular tour included general sportsmanship combined with athletic prowess. Ballplaying ability, it was made clear, would not be the sole determining factor.

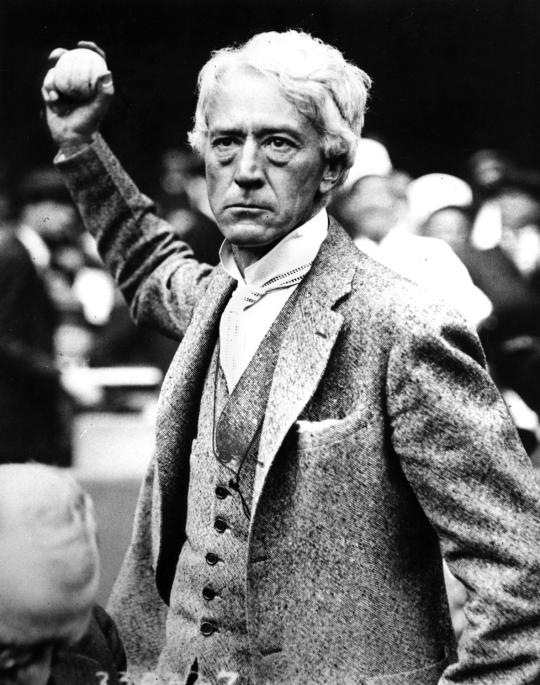

By June 1922, American League President Ban Johnson sanctioned Hunter’s tour.

“Herbert Hunter, as coach of Waseda and Keio universities, has performed a great work in arranging such a tour,” Johnson said. “These players will be missionaries and will preach the glories of the greatest game in the world. They will represent America in Japan and may be the means of promoting a lasting bond of goodwill and understanding between the nations.

“I view this trip as an educational tour; the men are not to receive any pay but will be the guests of the colleges. This, of course, removes the trip from the barnstorming category. Therefore, no rules will be violated, and there can be no objections, as I see it, from any of the club owners,” Johnson said. “Perhaps someday we will have the champions of America meeting the winners of the Japanese series in a real world’s series. This may be my dream, but it is a dream I shall cherish until it materializes.”

In October 1922, it was announced that the Advisory Council of Baseball, made up of Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis, National League President John Heydler and Johnson, had officially sanctioned the trip to be made by a team of big league ballplayers that fall.

The Hall of Fame Library has in its collection a folder of documents related to the 1922-23 tour of Asia, including a tentative itinerary, a brochure produced by the Spalding sporting goods company giving thumbnail bios of the participants, letters from Hunter and George Moriarty, and a blank player contract.

In a missive from Moriarty to Landis, dated Nov. 4, 1922, Moriarty – a longtime umpire – relayed news of Pennock’s first overseas action.

“The All Americas defeated the Keio University nine today in an interesting game, by a score of 6 to 0,” Moriarty wrote. “Pennock, for the All Americas, pitched an excellent game, and succeeded in holding the Keio batters practically helpless throughout the nine innings. The All Americas played a brand of baseball that was up to the major league standard in every respect. While the game was not a spectacular performance, it contained several fine fielding features, and Falk’s home run in the seventh inning provided the finishing touch for the occasion. Needless to say, the Japanese fans were highly pleased with the exhibition today. The attendance was approximately six thousand. You will please find enclosed herewith a review of the game, from the Japan Advertiser of November 5.”

As the Hunter team was travelling to Vancouver to board the steamer for Japan, a Landis letter made public explained his confidence in the outcome.

“While this trip,” the letter said, “is not in response to any official invitation from the government of Japan, the circumstances attending the invitation and its acceptance, to a considerable degree, distinguished it from a purely private enterprise and make it representative of American baseball. Consequently, the Advisory Council has authorized Mr. Moriarty to accompany the parts as its representative, as it is keenly interested in having the tour reflect credit upon our national game and its professional players. Of course, the players appreciate the necessity and importance of maintaining the high standards of play and sportsmanship and of personal conduct on and off the field, which they observe during the regular championship season. The personnel of the party is such that we have the utmost confidence that this will be done.”

The Sporting News, the self-described “Bible of Baseball,” editorialized its tacit approval of the tour in its Nov. 11, 1922 issue:

“There have been more ambitious tours undertaken by American baseballers to the Orient and even around the globe, but none that will be watched with greater interest than attaches to the trip now underway by a party recruited by Herb Hunter, because this jaunt has been given official sanction from the highest baseball authority and an official representative is sent along with it, in the person of George Moriarty, to see that it really is representative and so conducted that it will reflect credit on the national game and indeed be something like spreading the gospel of baseball.”

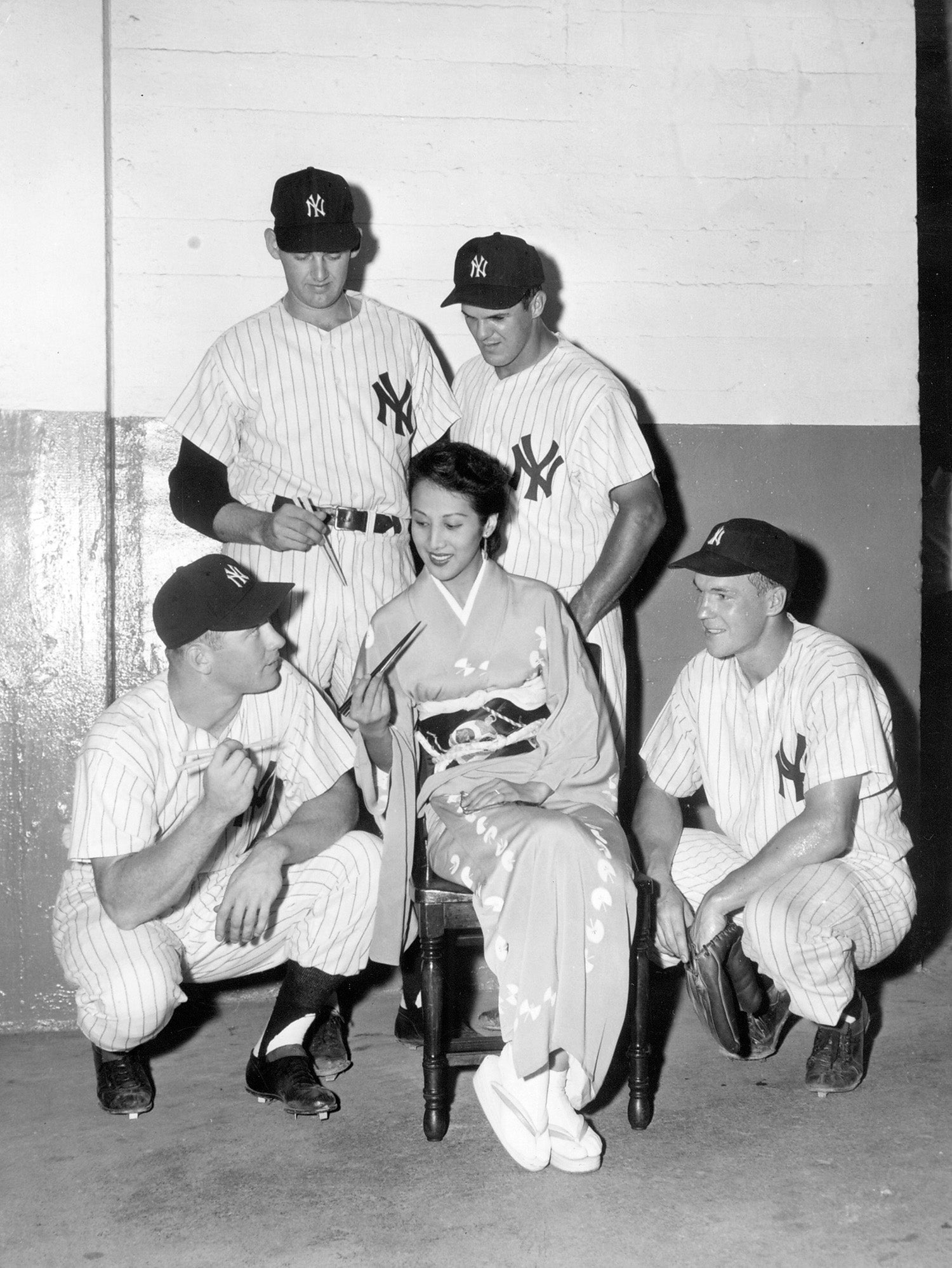

The “Baseball Mission to the Orient” left Vancouver on Oct. 19, 1922, on the Empress of Canada, a 22,000-ton steamer, bound for Japan. A number of the ballplayer’s wives made the trip, including Mrs. Pennock and their daughter Jane.

“First party agrees to pay all necessary travelling expenses, hotel bills, meals from the home of the second party, until the itinerary, including the return home of the second party, has been completed,” the player contract reads in part. “This agreement is intended to and does cover all legitimate travelling expenses that may be necessary and proper in order to carry into effect the terms of this contract. This shall include all sight-seeing or side trips taken under the direction and supervision of first party. It is further understood and agreed that all transportation, lodging and meals are to be first class in every respect and the best service available is to be obtained. It is also agreed that a liberal allowance will be made by first party for all reasonable tips necessary to procure first class service, it being the object of first party to travel and accommodate his players in what is known as style deluxe.”

With the American ballplayers set to arrive, Captain Koch of the Hong Kong baseball team told reporters: “We don’t intend to let any ball men, no matter how big they are, pass through Hong Kong without trying conclusions with us. Let them come and we will at least make them hustle.”

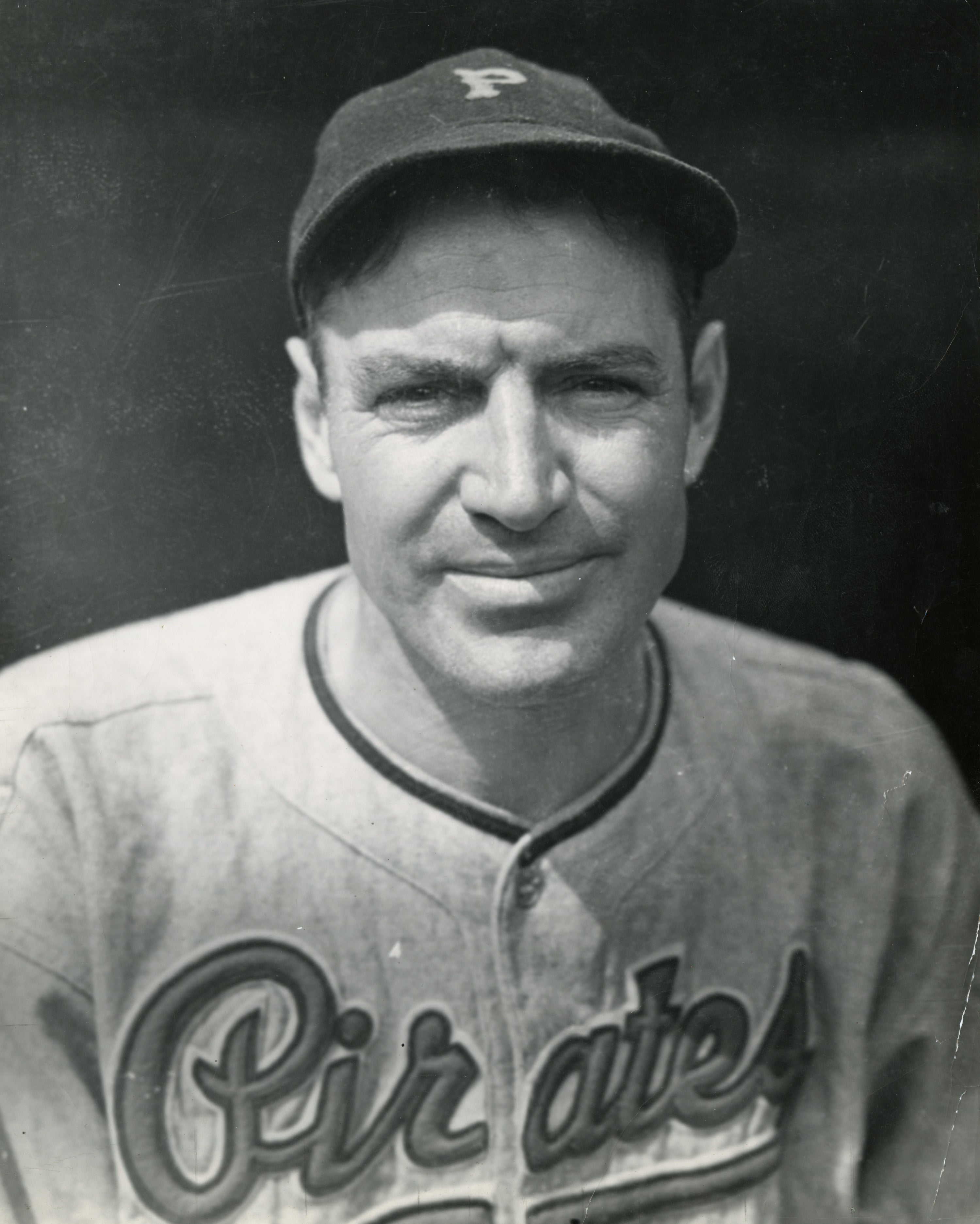

Ultimately, the tour proved successful except for one noteworthy event. On Nov. 19, 1922, an American team made up of big-league players lost to an Asian team, in this case a 9-3 defeat at the hands of the Mita Club made up of Keio University alumni, for the first time. Hoyt, the future Hall of Famer, gave up all nine runs.

In a letter from Moriarty to Landis, dated Nov. 19, 1922, the umpire wrote of the defeat at the hands of the Japanese squad.

“The Mita Club defeated the All-Americas by a score of 9 to 3 today,” Moriarty wrote. “Pitcher Hoyt suffering from a weak arm, which is the result of his work as pitching-coach to the university players during the past week, was batted freely. Errors by the All-Americas also aided the opposition in the scoring. Pitcher Ono of the Mita club pitched a surprisingly good game, and the hits he allowed were well scattered. The Mita club is composed of several Keio University players, and some of its graduates. The attendance numbered approximately 5,000.”

In January 1923, with the major league traveling party in Hawaii, Hunter received a complimentary message from Landis, according to the Honolulu Advertiser.

“Your performance has been a distinct contribution to baseball,” Landis wrote. “My congratulations and appreciation.”

Hunter’s response to Landis: “Thanks. We tried not to forget our purpose – that of playing America’s game like Americans.”

After traveling thousands of miles, the baseball touring group arrived back in the United States on Jan. 31, 1923. Hunter, in an interview with the San Francisco Chronicle, shared his thoughts on the experience.

“It’s grand to be back in good old U.S.A. I’m simply tickled to death to get back here in the States, though we have had the most wonderful time of all our lives in the Orient,” Hunter said. “The trip from the standpoint of international friendship we have done more than some of eminent diplomats or men of large affairs. I hope I may be able to take another team to Japan again in the near future. The boys over there played most wonderful baseball games, and it is only a question of time to show us that Japanese can hit and field just as well as our boys.”

As for his team’s only loss, Hunter explained, “Some people over there criticized us for letting the Japanese team win, as a compliment, but that is a gross accusation, because we did play with all our might, but we simply couldn’t solve the delivery of Ono, the Mita’s star pitcher, and we ultimately lost the game by a score of 9-3.

“Incidentally, that was the only game we lost in the entire trip. Our players were treated very generously and they were well pleased with the treatment. Aside from playing the game, our boys had a heap of good time.While Japanese players have acquired great skill and proficiency in pitching and fielding, batting has failed to meet other requirements. It would seem the pitchers have developed faster than the batters, but this apparent weakness, I believe, in time will be fully overcome.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum