- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: Bracelets have long given fans a chance to express their diamond passion

#GoingDeep: Bracelets have long given fans a chance to express their diamond passion

Baseball team merchandise was not always jerseys and caps sported by fans. In an era before a billion-dollar industry created these uniform replicas, men wore suits and fedoras while women wore dresses and hats to the ballpark.

Team merchandise was available in the form of pennants, buttons and other small collectibles. Fans also had the opportunity to demonstrate support for their teams with ornamental accessories – especially jewelry.

Within the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s collection there is a small subset of artifacts comprised of baseball bracelets. The Museum’s collection chronicles all of baseball history, including the important role played by the fans who bring the spark and joy to the game. These pieces of jewelry provide a snapshot into the lives of many female baseball fans who wore them and proudly supported their teams in a time before donning a jersey of their favorite player became societal norm.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

As early as the 1860s, ball clubs instituted Ladies Days to attract female fans. These ballpark events helped women foster a connection and interest in the game, while also encouraging the men in the stands to behave in a more civilized fashion (meaning less cursing, booing, drinking, and gambling). These days devoted to attracting women to the game were fairly frequent occurrences up until the 1980s.

At the turn of the 20th century, women began coming to the ballpark on their own terms, not just when the club enticed them with free admission. Donning dresses (which, up through the 1950s, included undergarments of corsets and girdles), these fans sat in the stands to root for their team because they loved the game. But even outside the ballpark, women could show team allegiances with jewelry such as charm bracelets.

A wrist accessory primarily worn by women, charm bracelets traditionally are made using a chain as a base with a variety of attached ornaments each relating to a common theme determined by the wearer. There is no exact date as to when a bracelet with attached charms or trinkets was first created, but the idea of carrying talismans as good-luck charms dates back to ancient times.

Charm bracelets grew in popularity through the early 20th century and hit their heyday in the 1950s. The accessory successfully came into vogue because it was a refined and eye-catching means for women to express their style and personality. Some charm bracelets were sold with baubles already attached, while others provided a blank slate for the wearer to add their own individual charms. These personally chosen charms could express an important event or memory for the wearer, creating, in a sense, a memoir that was worn on the wrist.

Bracelets With Charms Included

Three of the bracelets in the Museum’s collection were created and sold as a completed piece of jewelry with the charms already attached. These artifacts each revolve around a singular theme: a team. Research hasn’t revealed when team bracelets first debuted on women’s wrists, but the three in the collection provide an idea regarding when teams were producing this type of merchandise.

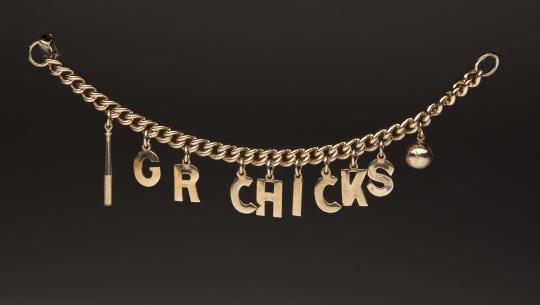

Perhaps surprisingly, the oldest team bracelet in the collection was not related to a major league franchise – it commemorates a team in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL). The Grand Rapids Chicks bracelet was produced in the latter half of the team’s existence. Part of the AAGPBL, the Chicks formed in 1945, two years after the league’s inception, and only disbanded once the league shut down in 1954. This gold-colored bracelet features the letters “GR CHICKS” bookended by bat and baseball charms and was purchased in the Chicks’ gift store in the early 1950s.

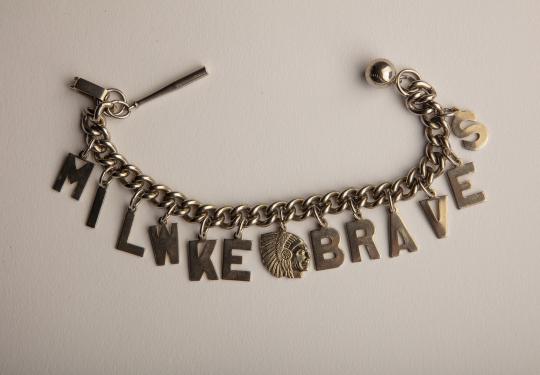

Close in age to the Chicks bracelet, the Museum’s next team bracelet hails from Wisconsin. From 1953 to 1965, the Braves called Milwaukee home. In those thirteen years, the team won the National League pennant twice and won the franchise’s second World Championship in 1957. Offering a variety of team merchandise, such as buttons, hand-held fans, and drinking glasses, the Braves marketed Milwaukee charm bracelets to their female fans. The silver plated version in the collection spells out the team name (shortening Milwaukee to “MILWKE”), has bat and baseball charms at each end and a charm with the team’s logo in between “MILWKE” and “BRAVES”. This type of charm bracelet, available in the mid- to late-1950s, regularly sold for 75 cents to a dollar.

The last team bracelet in the collection was created in 1969, the only season that the Seattle Pilots existed. In that year, the franchise went all out on producing themed souvenirs. Beyond standard tchotchkes of key chains, pennants, and ash trays, the passionate Pilots fan could also purchase replica warm up jackets (in boys sizes), infant bibs, beverage coasters, and three different styles of bracelets, available in both regular and pre-teen sizes. The Seattle Pilots bracelet in the Museum’s collection advertised for $2.50 and featured four charms: a glove, bat, a player mid-swing and Pilots logo.

Not all commercially-sold charm bracelets were team-specific. Several were advertised with generic baseball charms such as a bat, glove, and ball. By mailing a coupon and box tops from Quaker puffed rice or wheat to “Babe Ruth’s Baseball Gifts,” boys and girls could get a variety of baseball swag including a Babe Ruth signed photo, watch fob and bracelet. A popular 1935 newspaper advertisement claimed that “every girl will want this stunning bracelet … to complete her sports costume.”

Marketing to women, the March 12, 1950, edition of The Cedar Rapids (Iowa) Gazette ran an advertisement for a baseball bracelet manufactured by Coro, one of the largest costume jewelry manufacturers in the U.S. in the mid-20th century. Selling for $1 plus tax (about $10.89 in today’s money), the “smart, heavy silver-finish new-styled bracelet with a miniature baseball and bat attached to the heavy silver chain ... [is a] perfect touch for your new casual spring clothes, for yourself, or for a gift.”

By the 1950s, the heyday of charm bracelet manufacturing, baseball infiltrated everyday life by capitalizing on the production of team merchandise, including products like the charm bracelets mentioned above. With these accessories, women had the ability to illustrate their love of the game outside of the ballpark.

Adding Charms to Bracelets

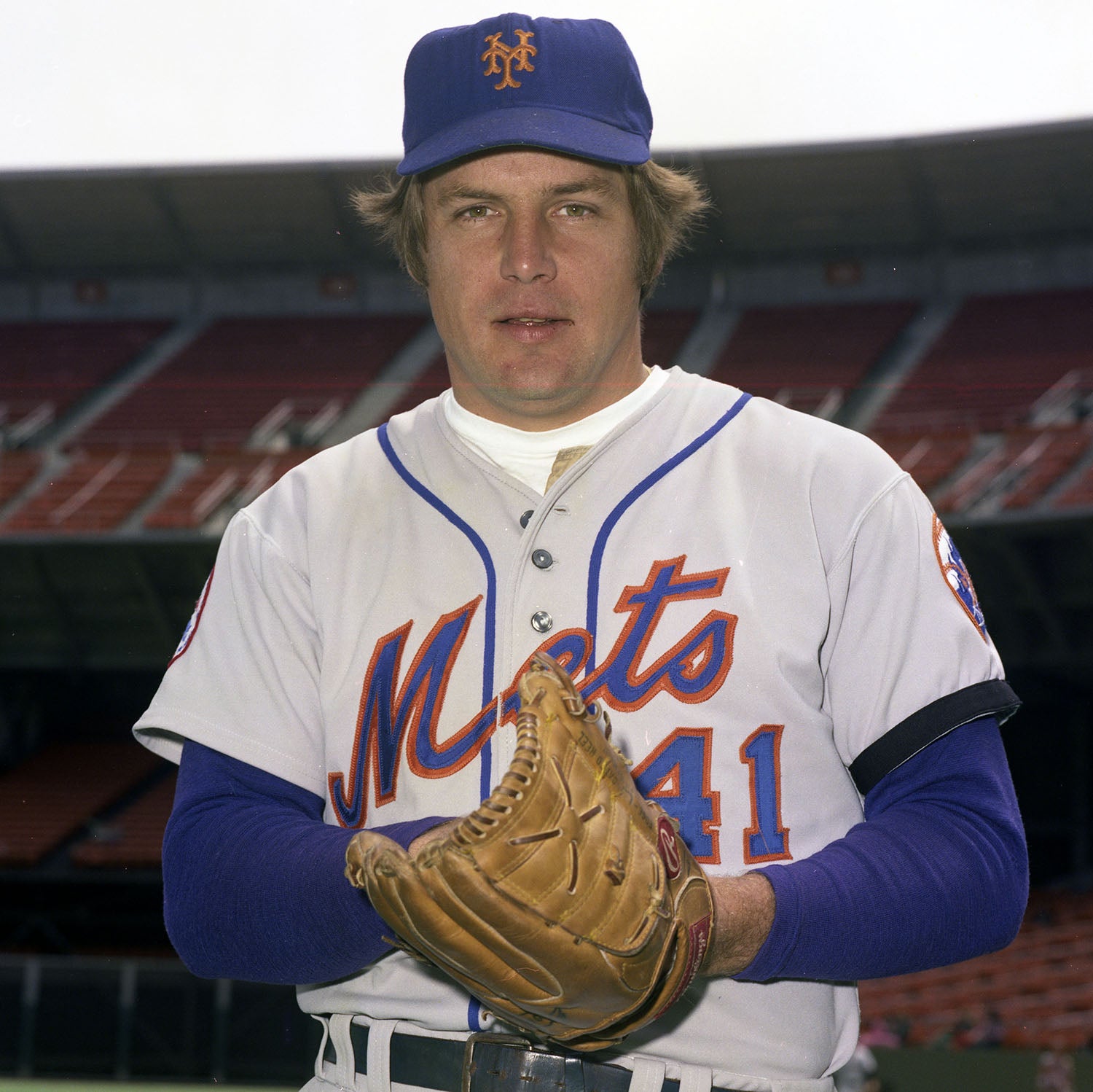

The Oct. 10, 1969 edition of The Baltimore Evening Sun quoted an article written by Nancy Seaver, wife of future Hall of Famer Tom Seaver, for a New York newspaper in which she talks about her “lucky baseball charm bracelet.” She notes that she already has a charm for her and Tom’s poodle and several related to his then-three-year big league career, including one for his uniform number (41), one representing his 1967 Rookie of the Year Award, and a pair representing his appearances in the ’67 and ’68 All-Star Games. She goes on to say that “pretty soon I’ll be adding a gold pennant. And after that a 1969 World Series charm.”

The article had been published just days after the Mets had clinched the NL pennant and shortly before the beginning of the World Series. Nancy accurately predicted the outcome of the Series with the ’69 Miracle Mets clinching the franchise’s first Championship in five games over Baltimore.

The Museum’s collection includes several artifacts in which the bracelets’ owners collected charms. Hazel Weiss, the wife of baseball executive and Hall of Famer George Weiss, owned at least two baseball charm bracelets. Like Nancy, Hazel appeared to have added charms during significant moments during her husband’s nearly two decade-long career as a general manager for the New York Yankees and New York Mets.

Both of Hazel’s bracelets are decorated with press pins that had been converted to charms by removing the pin back and soldering a metal loop to the top of the pin. One bracelet features 18 charms while the other has six. Upon closer inspection, charms representing the Yankees World Series wins are present. Though Weiss’s last year as General Manager of the Mets was 1966, one of the bracelets includes a charm for the 1969 Mets World Championship, a team that he had helped assemble. There are also charms related to the Orioles, Dodgers, and Angels, representing various World Series and All-Star Games, contests that the Weiss’ most likely attended and wished to remember.

Emilie Mulholland, who worked in the Pirates front office from 1955 to 1964, had not one but three bracelets to which she added charms. In a similar vein to Hazel, Emilie’s bracelets were filled with press pins that had been converted to charms, documenting significant games that she likely attended as part of the club’s Public Relations team. One of her bracelets features 21 charms, including a Pirates 1960 World Series charm, several nonspecific baseball charms such as a catcher’s mask, and other personal, non-baseball related charms that likely documented other facets of her life, such as a “Love Letters” mailbox, an Olympic Games crest and a spinning horseshoe.

A baseball devotee, Emilie stated in an interview with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette published April 16, 1957, that she grew up playing on a team that had both boys and girls. Her father was such a devoted Philadelphia Athletics fan that she didn’t know the Phillies existed in the same city until she was a teenager. She first joined the Athletics as a PR department volunteer and then was hired as an usher in 1950, working there until the franchise moved to Kansas City four years later. Still desiring to continue her work in baseball, Emilie sent letters to dozens of baseball clubs and was ultimately hired by the Pirates in 1955. She worked in Pittsburgh for almost a decade until she returned to Philadelphia to work for her alma mater, Temple University, with her bracelets documenting her time and memories with the Pirates.

Love in Baseball Bracelets

The final group of baseball bracelets in the Museum’s collection are perhaps the most unusual and heart-warming. While not charm bracelets in the traditional sense, these pieces of jewelry, like the artifacts previously mentioned, demonstrate the wearer’s love of the game. These accessories were not purchased from an ad in a newspaper or collected one charm at a time. The facets that make up these bracelets were won – not by the women who wore them, but by their baseball husbands, and thus they represent both a love for the game and for a spouse.

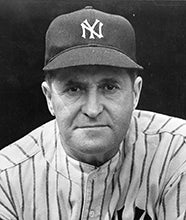

Joe McCarthy never made it to the majors as a player, but for almost a quarter of a century, he successfully led three franchises as a manager. Spending most of his career in New York, Joe skippered the Yankees from 1931 to 1946. In those 16 years, he piloted greats such as Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and Joe DiMaggio as the club captured eight American League pennants and seven World Championships. McCarthy had his World Series rings refashioned as charms and placed them on a bracelet created especially for his wife, Elizabeth “Babe” McCarthy.

The bracelet, connected with fine chain links, has seven medallions with diamonds, each representing a New York World Championship. Four semi-triangular pieces, two on each side of the center five medals, are the sides of his 1937, 1938, 1939, and 1941 rings. Over the years, additions were made to the bracelet which bears the inscription “To My / Loving Wife / Babe McCarthy.” Through this bracelet, Babe was forever linked to her husband’s managerial success, and by donating this bracelet to the Museum following her death in 1971, Joe ensured it would last for generations to come.

Five years before Babe received her gift from Joe, Lou Gehrig presented his wife, Eleanor, with a bracelet made up of not only his World Series diamonds, but also medallions commemorating his other accomplishments on (and off) the field. Featured in The Pride of the Yankees, the 1942 biographical film about Lou’s life and career, the original bracelet, not a movie prop replica, was used on set.

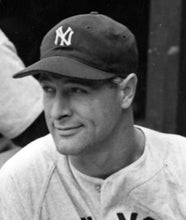

A four-year wedding anniversary gift, the bracelet was created in 1937 from the many pieces of jewelry that Lou had already accrued during his then 15 years in the big leagues. At the center is a medallion comprised of his 1935 and 1937 All-Star Game awards, with “To Eleanor / with all / my love forever / Lou / Sept. 29, 1937” engraved on the reverse. Spanning from the center are two rows of medals that commemorate Lou’s other All-Star Game appearances, Most Valuable Player awards, and diamonds from his World Series rings. After he gave Eleanor the bracelet, a new medal documenting New York’s 1938 Series win was added close to the right clasp. Most likely, Lou had a jeweler melt and then recast his Championship rings in order to create the charms for the bracelet.

When Eleanor wore this piece in the years following Lou’s death, this collection of his awards no doubt provided her with more memories than a “traditional” charm bracelet ever could.

The bracelets in the Museum’s collection tell the story of women who were a part of baseball – some as fans, some as employees, and some as wives - from a time when it wasn’t conventional to broadcast one’s favorite teams or players by donning jerseys and caps in public. Instead, in the form of jewelry, women found more delicate, and often more personal ways to express their special connection to baseball.

From team-specific bracelets to more personalized charm choices, these accessories in the Museum’s collection shed light on the female fans of our National Pastime. In more ways than one, the old adage is true: Diamonds are a girl’s best friend.

Gabrielle Augustine is a curator at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum