- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: Christy Mathewson, Helene Britton and the theater

#GoingDeep: Christy Mathewson, Helene Britton and the theater

While performing quality control on records is not the most interesting task in the world, the stories that appear while doing so can be.

Take for instance, an image of Christy Mathewson and William Courtenay, a Broadway and film actor, that came across my desk recently. The sepia-toned photograph shows the two standing in the outfield of a baseball field shaking hands and smiling at each other. Though the picture is not extraordinary, a caption on the back reading “Christy Mathewson and William Courtenay in the Girl and the Pennant at the Lyric Theatre October 23rd” leads to the real story.

Christy Mathewson, actor? Nope. Christy Mathewson, playwright? Sort of.

In November 1912, after the baseball season ended, Mathewson began discussing the possibility of creating a play about baseball with playwright Rida Johnson Young. Young was well known for her work on Broadway and was the perfect fit for writing a sports-themed play. Her first Broadway play, Brown of Harvard, debuted in 1906 and revolved around a young man and the Harvard rowing team. The play was later adapted for the silver screen in 1911, 1918 and 1936.

In an interview conducted by Della Mac Leod of the New York Press on Oct. 19, 1913, Mathewson explained how the two became a writing duo. “Young, being a playwright [was] looking for material, as a matter of course, and [she] had the idea for a baseball play,” feeling that there “was a great deal of dramatic interest in the game.” From there a partnership was formed, and the two started discussing material for the play.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Mathewson went on to explain in the interview that around this time “a woman owner of a baseball team in the West was having her own troubles with her team, and I thought the idea of having a woman owner of a ball team was a good idea to start on.” A woman protagonist might also, as Mathewson said, “enlist the sympathetic interest of all the women who form so large a part of the theatergoing public.” The woman in the West that Mathewson drew inspiration from was none other than Helene Robison Britton, the owner of the St. Louis Cardinals.

In March 1911, Stanley Robison, the owner of the St. Louis Cardinals, passed away, causing quite the stir in both the worlds of sports and society. Robison’s will revealed that he left controlling interest of the team in the hands of his 32-year-old niece and married mother of two, Helene Robison Britton. The remaining shares in the team were bequeathed to Helene’s mother - Stanley’s sister-in-law - Sarah Carver Hathaway Robison. Many in the baseball world wrote this off as a fluke, believing there was no way the pair would maintain ownership of a team. Britton and her mother shocked them all by not only refusing to sell their shares in the team, but also by Britton moving to St. Louis and taking an active role in the management of the team for six years. Unfortunately, it is unclear what role Britton’s mother played during her six years as minority owner. The only times she is mentioned during that time period is when initially she received the shares and when she passed away in 1919. Even then, the papers don’t mention her status as the former minority owner of the team, electing instead to mention her husband and daughter as the owners instead.

Over her six years as team owner, Britton faced adversity and sexism from both in and outside of baseball. The media often joked about the baseball “magnette” and her influence on the game. One newspaper even joked that the Cardinals’ uniforms might include bloomers because of her.

While Britton initially supported and trusted the team’s popular manager (and future Hall of Famer) Roger Bresnahan, she quickly grew frustrated by him. Bresnahan frequently offered to buy the team from Britton. At the end of the 1912 season, Bresnahan was released from the team after various arguments with Britton, once angrily telling her that “no woman [could] tell him how to run a ball game!”

At a 1916 meeting, Britton’s fellow National League team owners tried to force her to sell the team as part of the peace treaty with the Federal League. They claimed that the sale would be “for the good of the game.” Britton calmly refused and walked away from the meeting. While she came away with her team and stadium intact, the Federal League folded (which is most likely what the National League wanted anyway). Later that year Helene assumed the role of team president, ousting her soon-to-be ex-husband.

Nevertheless, Britton persisted. She lured female fans to the park with Ladies Days, where all ladies with a male escort were admitted to the grandstand for free. She also hired entertainment to perform between innings to draw in families, paying crooners to sing to the crowds. Not only did she draw crowds, but under her ownership the Cardinals rose to third place in the standings twice, once in 1914 and once more in 1917. This was the highest the Cardinals had ranked since being purchased by the Robison brothers in 1899.

Unfortunately, due to financial strain, Britton was forced to sell the team in 1918 to a local group of St. Louis businessmen led by Sam Breadon for $350,000. Based on the Robison’s original investment of $40,000, Britton netted a healthy profit on the sale. The profit margin didn’t matter to Britton though. Later in life she would say that she loved baseball and regretted her decision to sell the team. When asked about her success in baseball, Britton said “All I ever needed was the opportunity. That’s all any woman needs.”

Inspiration in hand, the result of Mathewson and Young’s collaboration was The Girl and the Pennant. News of the collaboration broke as early as April 8, 1913 when The New York Times published an article that Mathewson was “about to enter the field as a playwright.” The paper added that Mathewson was helping Young with the baseball aspect of the play. It should be noted that it is unclear how much time Mathewson was able to devote to the play once baseball season was in full swing, though it was claimed he made multiple trips to Connecticut to work on the script. Nevertheless, the script was completed and the play was ready for its test run in the beginning of October.

After a two week delay – thanks to Mathewson’s participation in the World Series – the play debuted at the Lyric Theatre, a prominent Broadway outpost, on Oct. 23, 1913. The play centers around Mona Fitzgerald, new owner of the Eagles professional baseball club, whose deceased father bequeaths his team to his only child. While Fitzgerald wants nothing more than to make her father proud, she worries that she doesn’t have the ability to do what her father couldn’t: Help the Eagles win a pennant.

This is a taller order than Fitzgerald realizes, as the team’s manager, John Bohannan, will do anything it takes to rid the team of her ownership. Upon arriving in Texas to watch the Eagles practice during Spring Training, Bohannan tries to convince Fitzgerald that she should sell the team to Mike Freeland, an unseen financier who has promised half-ownership to Bohannan.

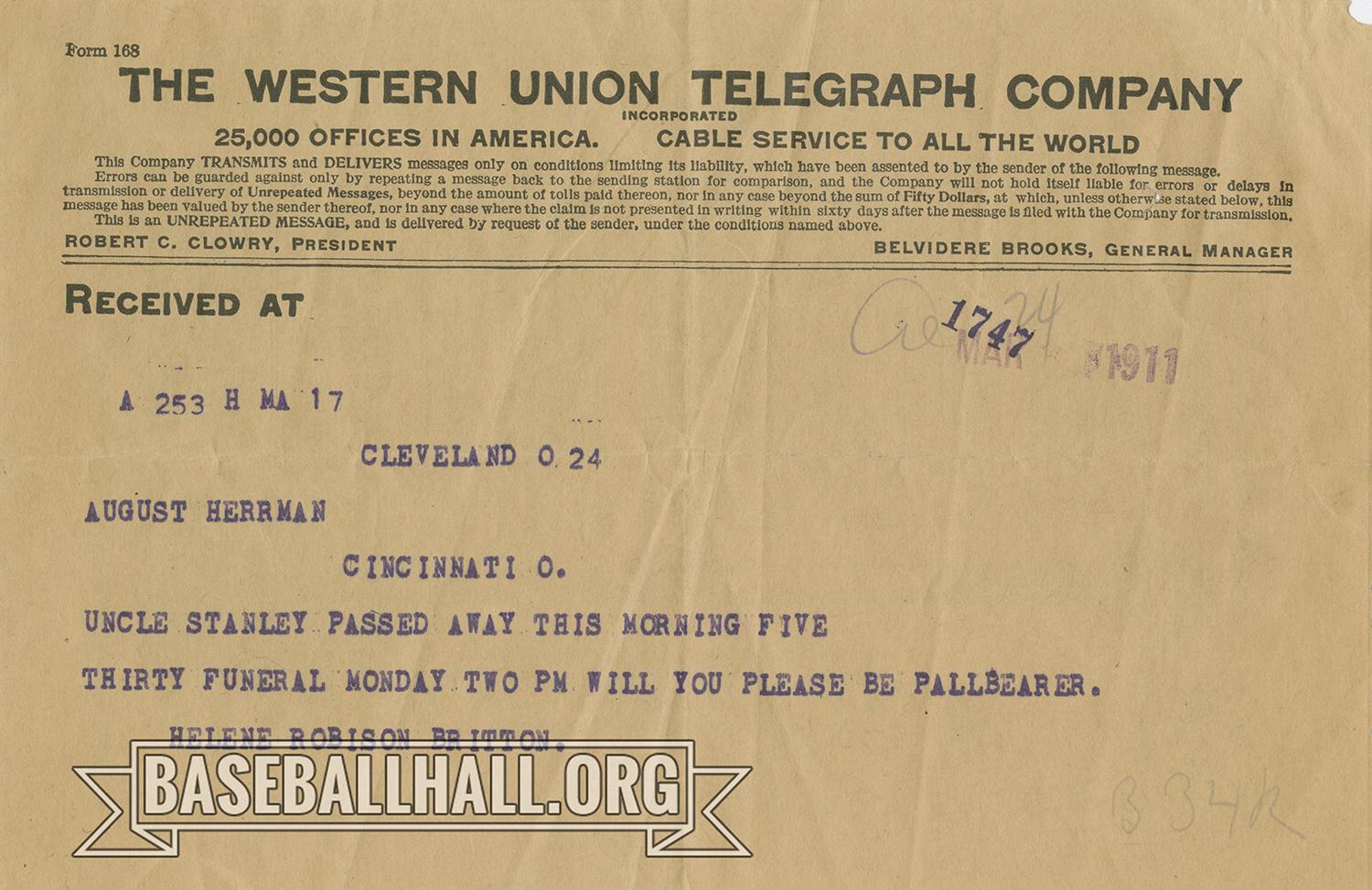

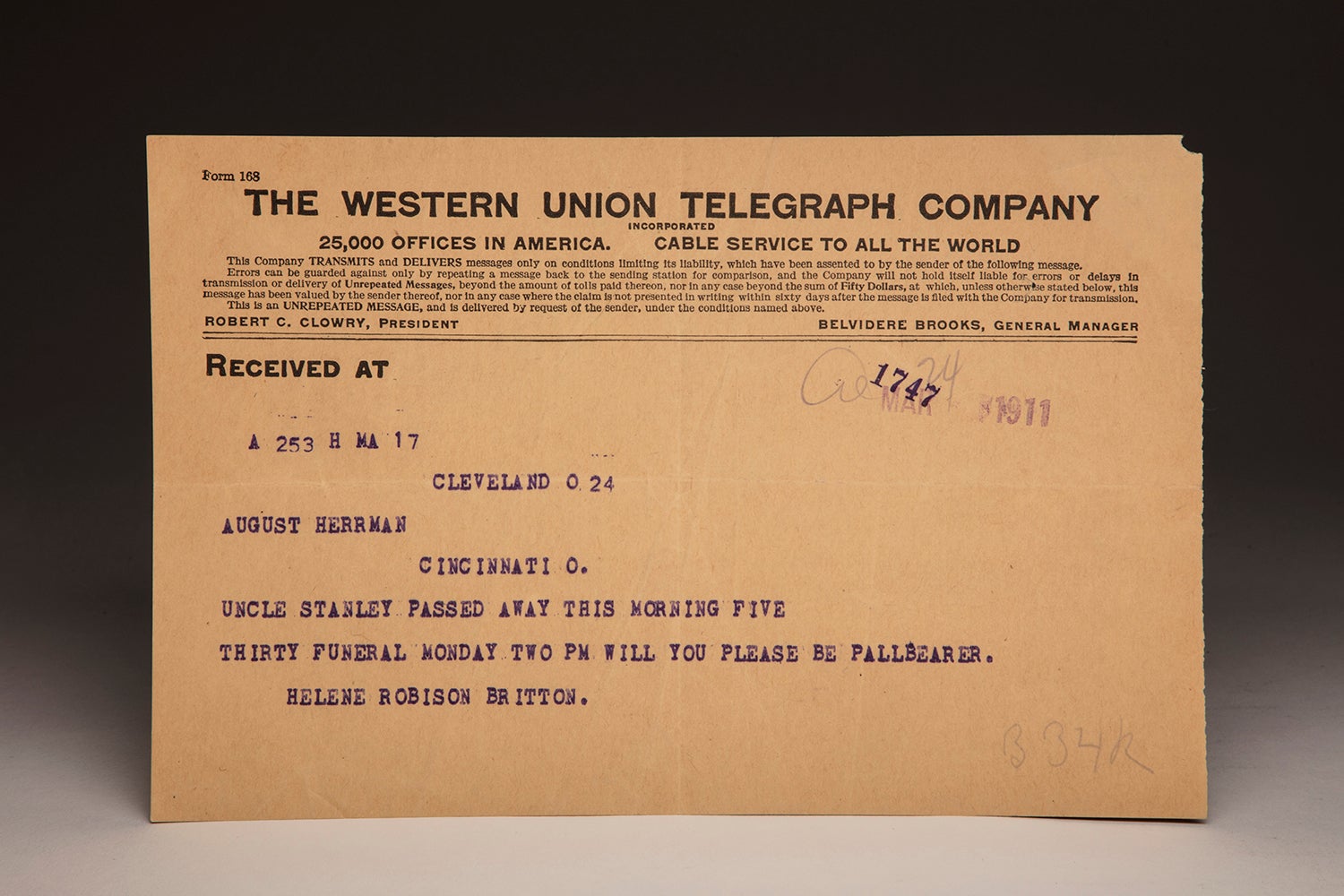

Pictured above, a Western Union telegram from Helene Britton to chairman of the National Commission August Herrmann dated March 1911 informing him that Britton’s uncle, Stanley Robison, had passed that morning. Britton would become the owner of the St. Louis Cardinals. PASTIME (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Fitzgerald almost goes through with it, but changes her mind when she receives an encouraging note from a mysterious man in a private car. She exclaims to the crowd of ballplayers and friends, including brothers Copley and Punch Reeves, that “it’s just what [she] needed to buck [her] up! Well, ‘Mr. Private Car-man! [She doesn’t] know who you are, but [she’ll] take your advice. [She’ll] stick and [she] won’t be bulldozed. [She] won’t be dictated to… [She’s] going to be [her] own man! [She’ll] stick!” With Fitzgerald’s refusal to sell the team, a deal was put forth by Henry Welland (the owner of the Eagles’ rival the Hornets) for Bohannan to throw the season. By throwing the season the pair hoped to discourage Fitzgerald enough that she would sell the team.

Between the first and second acts, unseen by the audience, the Eagles, under Fitzgerald’s ownership, climb the ladder until they reach first place, with the Hornets in a close second. With the league championship two games away, Fitzgerald invites her team, as well as rival owner Welland, to her estate for an afternoon party. It is there that Copley’s suspicions regarding Bohannan deepen. He converses with Welland, who claims not to have ever met Bohannan. Welland also denies being in Texas during the Eagles’ Spring Training and making a deal of sorts with Bohannan. This lie crumbles within minutes though, when Bohannan not only walks in and greets Welland, but tells Copley that he’s known Welland since before Copley was born.

Once Welland and Bohannan realize that Copley is on to them, Bohannan breaks down, begging Welland to let him out of the deal. People were already upset with managing decisions he had made recently. There was no way he could throw the remaining three games. And on top of that, he had had a change of heart about Fitzgerald, growing to like the female owner.

Unfortunately, Welland has an iron-grip on Bohannan because of his debt to him. So to keep their plan under wraps, Welland plans to purchase Copley from the Eagles. This plan is quickly foiled by Copley himself, who offers to pay Bohannan’s debt.

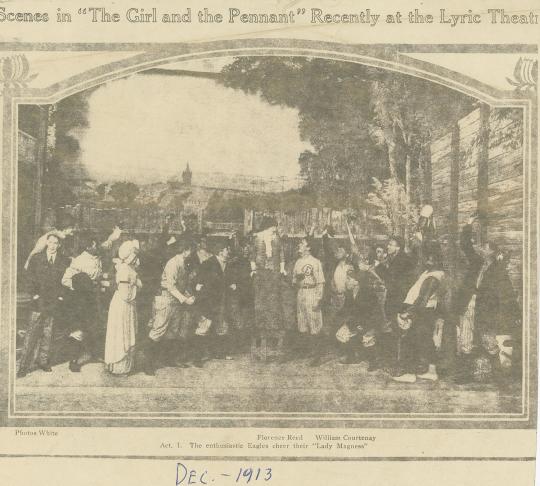

In November 1912, after the baseball season ended, future Hall of Famer Christy Mathewson began discussing the possibility of creating a play about baseball with playwright Rida Johnson Young. The play, pictured above, was titled "The Girl and the Pennant." (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Christy Mathewson (left) shakes the hand of actor William Courtenay, with whom he collaborated to create the play, "The Girl and the Pennant." PASTIME (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

His dastardly plan squashed, Welland pulls one last trick from his sleeve. Knowing that Copley’s brother, and the Eagles’ star pitcher Punch, is struggling to stay sober, Welland convinces Punch to join him and a few showgirls for dinner the night before the pennant game.

Welland’s plan is unfortunately successful, and Punch is brought home drunk by teammates the morning of the game. Copley and their teammates cover for Punch, and keep his secret from both Bohannan and Fitzgerald. With their star pitcher incapacitated, the Eagles head to the field to play for the pennant.

The height of the play comes in the third act when the Eagles and Hornets play the pennant game. The action takes place offstage, but the audience follows the game with narration from Sam, the team’s trainer. He gives a play-by-play to Fitzgerald, who is too nervous to watch. It’s the ninth inning, and the Hornets lead 2-1. The Eagles are able to hold them in the top of the 9th, and they reach their final chance to win the pennant in the bottom of the inning.

Punch, sober now, reaches the field with enough time to follow Sam’s play-by-play, as he is not allowed on the field. The Eagles get two runners on base, and at the last second, Bohannan puts Copley in to pinch hit. With a 1-and-1 count, Copley hits a triple that brings in the two runners and secures the pennant for the Eagles.

The play concludes at Fitzgerald’s estate. Characters meet there as an investigation begins regarding Bohannan and Copley’s deal. Like all good heroes, Copley saves the day and sends Welland packing, while also clearing his and Bohannan’s name. Fitzgerald is presented a facsimile of the pennant by members of the Eagles, but later confides in Copley that she plans on leaving for Europe, her reputation ruined by Bohannan. Copley claims that she can’t because he loves her and implies they can own the team together. Fitzgerald, overwhelmed with emotion, falls into Copley’s arms and the play ends.

Reading the script, Britton’s influence on Young and Mathewson’s play is apparent. Like Britton, the play’s protagonist also inherits her team from a deceased relative. Fitzgerald, like Britton, also turns down a large offer to sell the team before her first season as owner begins.

The team’s manager, John Bohannan, is a thinly veiled stage-version of the Cardinals former manager, Roger Bresnahan. The plotline revolving around Bohannan’s game-fixing is inspired by accusations against Bresnahan of the same nature in 1911, though these were unfounded. Young and Mathewson cheekily acknowledge this in the first act when a friend of Fitzgerald’s “accidentally” calls Bohannan “Mr. Bresnahan” (to which he simply replies “Bohannan!”).

Comparisons have even been made between Copley and Christy Mathewson. Mathewson, universally liked by both players and fans, was often seen as baseball’s “golden boy”. Copley, like his creator, is well-respected by his teammates and managers, as well as the fans. And like Mathewson, Copley gets to step in and save the day.

While it received mostly positive reviews, The Girl and the Pennant was a flop. After only 20 shows, the play ended its run in early November 1913. Looking back on her career during a 1920 interview, Johnson called it the only flop of her career – which is saying something, as she became a Hall of Famer in her own right when she was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1970. However, the play did live on as a weekly serial in The Evening World, running from Nov. 3-8, 1913.

It’s important to acknowledge that the play is by no means perfect and it’s easy to see why it failed. Many disliked that the pennant game, the climax of the play, took place offstage. Though staging action scenes offstage was fairly popular during that time period, the audience disliked that the play’s most pivotal scene was heard, not seen. The racist depictions of and remarks made regarding Sam, the African-American trainer, and Chief, a Native American baseball player on the Eagles, are also hard to ignore. Not to mention the over dramatic end with Fitzgerald fainting in Copley’s arms when she discovers that he saved the day and loves her back. Maybe this is why Mathewson was a no-show for opening night, instead opting to start his barnstorming tour with the Chicago White Sox and New York Giants.

Or it could be that he wasn’t very invested. As mentioned before, how much Mathewson actually wrote for this play remains a mystery. Some newspapers credited Mathewson with writing his fair share, while others stated that he simply helped with the baseball lingo. Others point out that Mathewson loved money to the point where he would lend his name to just about anything that wasn’t alcohol-related (his devoutness to religion and his mother prevented that). Most importantly, when the play was published as a book in 1917, Mathewson’s name was nowhere among its pages.

Hall of Famer Christy Mathewson swings a golf club as his teammates look on. PASTIME (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Regardless of how much (or how little) Mathewson contributed to The Girl and the Pennant, he had to know what he was implying by attaching his name to it. Christy Mathewson, one of the most-well liked and popular players in the big leagues, supported the idea of females in baseball. Sure, Mona Fitzgerald is saved by a man by the end of the play. But Young and Mathewson spend the first three acts showing how the Eagles became a better team under her tutelage. She did what the man before her couldn’t: Produce a pennant-winning team.

The most bizarre part of this story might be that there was no press coverage regarding the similarities, most electing to stick with reviewing the play. The only person to actually acknowledge it was Mathewson himself during the interview with the New York Press. By publishing stories about the clear parallels and the success of Mona Fitzgerald entering the world of baseball, would the newspapers, who spent their time gibing about her, be admitting that Helene Britton could be good for baseball too?

Unfortunately, this is something we may never have a complete answer to. However, it may not matter. While she did end up selling the team in the end, Britton helped to bring about success to the Cardinals while being one of the first women to play an active part in the day-to-day operations of a baseball team. The opinions of the press regarding Britton, or her onstage counterpart, never seemed to phase her. She did what her uncle couldn’t do: Bring some success to the Cardinals.

Jamie Brinkman was the Digital Asset Manager at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Source Material

Claunch, Amanda. “Play Ball!” Missouri Historical Society (http://mohistory.org/blog/play-ball/) (April 2, 2010).

Edelman, Rob. “An Early Baseball Play and an Early Baseball Novel: Who Wrote ‘em?” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game, Vol. 8 (January 9, 2015).

MacLeod, Della. “She Did It,’ Modest ‘Matty’ Says of New Play, Then Delegates Mrs. Young to Bow.” New York Press (October 19, 1913).

“Mathewson A Playwright.” New York Times (April 8, 1913).

Mathewson, Christy. “The Girl and the Pennant, A Romance of the National Game: Novelized From Christy Mathewson’s Play of the Same Title.” The Evening World [New York, New York] (November 3-8, 1913).

Roessner, Amber. Inventing Baseball Heroes: Ty Cobb, Christy Mathewson, and the Sporting Press in America. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press (2014).

Stern, Travis. From the Ball Fields to Broadway: Performative Identities of Professional Baseball Players on the Nineteenth and Twentieth Century American Stage. Doctoral Dissertation. Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois (2011).

Stern, Travis. “Staging a Feminist Movement in Baseball,” in Baseball/Literature/Culture: Essays, 2008-2009, edited by Ronald E. Kates and Warren Tormey. Jefferson, NC: McFarland (2010).

Thomas, Joan M. Helene Britton. Society for American Baseball Research Bio Project (http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/ecd910f9) (March, 2018).

Young, Rida Johnson. The Girl and the Pennant: A Base-Ball Comedy in Three Acts. New York: Samuel French (1917).