- Home

- Our Stories

- Hall of Famers served in World War I Gas & Flame Division

Hall of Famers served in World War I Gas & Flame Division

The Great War initiated chemical warfare on a grand scale.

It began with tear gas in the summer of 1914, and by 1917, the German, French and British were assailing one another with deadly chlorine, phosgene and mustard gas.

The United States responded by creating the Chemical Warfare Service in the summer of 1918 to combat the gas attacks. The elite corps, commonly called “The Gas & Flame Division,” recruited top athletes to fill its ranks.

“We do not just want good young athletes,” Major General William L. Sibert said. “We are searching for good strong men, endowed with extraordinary capabilities to lead others during gas attacks.”

During the course of the war, 227 major leaguers served the United States through various branches of the Armed Forces. Several Hall of Famers, including Christy Mathewson, Branch Rickey, George Sisler and Ty Cobb, answered the specific call issued by the Chemical Warfare Service.

At least one may have paid the ultimate price as a result.

As the war instensified overseas, Major League Baseball owners, complying with the wishes of the federal government, reduced the 1918 season from 154 games to 128. But they resisted the draft, arguing that baseball should be considered an “essential industry,” one that buoyed the spirit of democracy, so their players would be exempt from conscription.

Secretary of War Newton D. Baker did not agree. On July 20, he decreed that “players in the draft age must obtain employment calculated to aid in the successful prosecution of the war or shoulder guns and fight.”

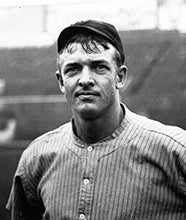

As a result, many players sought employment in defense industries stateside, where they were able to continue playing ball safely on company teams. The 38-year-old Mathewson, whose 373 career pitching victories and 2.13 ERA over 17 seasons would make him a member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s inaugural Class of 1936, was too old to be drafted but still felt compelled to join the cause on the front lines.

In late August 1918, the skipper of the Cincinnati Reds resigned his post and became Captain Mathewson, shipping to France for training with the new Gas & Flame Division.

Percy Haughton, perhaps best known as Harvard’s football coach, resigned as president of the Boston Braves in July to join the division as well, and convinced St. Louis Cardinals president Branch Rickey, 36, to enlist. Rickey was commissioned as a major and put in charge of the division.

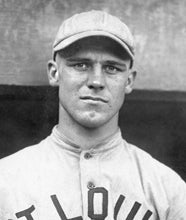

Rickey in turn recruited St. Louis Browns standout first baseman George Sisler, whom he had managed at the University of Michigan and with the Browns. Sisler, 25, looked up to Rickey as a mentor and was quickly persuaded to join the elite corps. After finishing the season, Sisler was commissioned as a second lieutenant and assigned to Camp Humphries in Virginia.

Ty Cobb, the Detroit Tigers’ 31-year-old star, had been granted a deferment since he had a wife and three children dependent upon him, but he refused to remain on the sidelines.

“I feel mean every time I look at a casualty list,” Cobb said. “I feel I must give up baseball at the close of the season and do my duty by my country in the best way possible.”

The following month, he signed up for the Gas & Flame Division, explaining that, “Christy Mathewson and Branch Rickey are in Chemical – they are guys I like and are friends.”

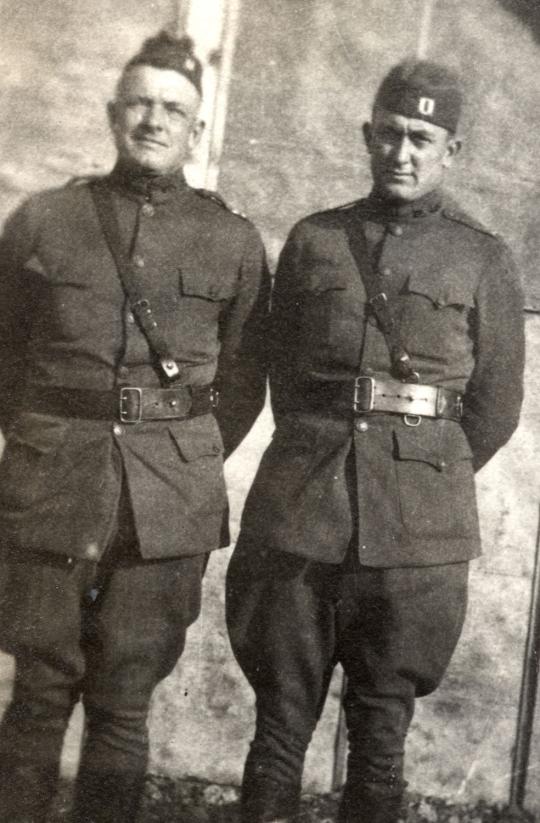

Commissioned a captain, Cobb finished the season with the Tigers, collected his 11th American League batting title with a .382 average, and joined Mathewson, Rickey and Haughton with the 28th Division at the Allied Expeditionary Forces Headquarters in Chaumont, France, 120 miles south of Paris, on Nov. 2, 1918.

The men of the Gas & Flame Division were charged with advancing across no-man’s land under cover of an artillery barrage, spraying liquid flames from tanks strapped to their backs and tossing gas-filled bombs like grenades into enemy trenches. They were still undergoing training when Cobb arrived. He and his baseball mates served as instructors, conducting realistic readiness drills, one of which sent soldiers into airtight chambers where actual poisonous gas was released. One day the drill erupted into chaos. Several men – including Cobb and Mathewson – missed the signal to snap on their masks. Cobb finally managed to get his mask on and groped his way to the door past a tangle of screaming men and thrashing bodies. “Trying to lead the men out was hopeless,” he said. “It was each one for himself.” Eight of his comrades died that day, their lungs ravaged by the gas. Eight more were crippled for several days. Cobb felt “Divine Providence” had spared his life, but Mathewson was not as fortunate.

“Ty, I got a good dose of the stuff,” he told Cobb. “I feel terrible.”

Armistice was declared on Nov. 11, 1918, before the division engaged in actual combat with the enemy. Rickey returned to the States in time to spend Christmas with his family. Since the fighting was over, the War Department gave Major League Baseball permission to return to its normal operations in 1919. Rickey resumed his role as president of the Cardinals, managed the team for seven seasons and built it into a champion with his famed farm system. He was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1967.

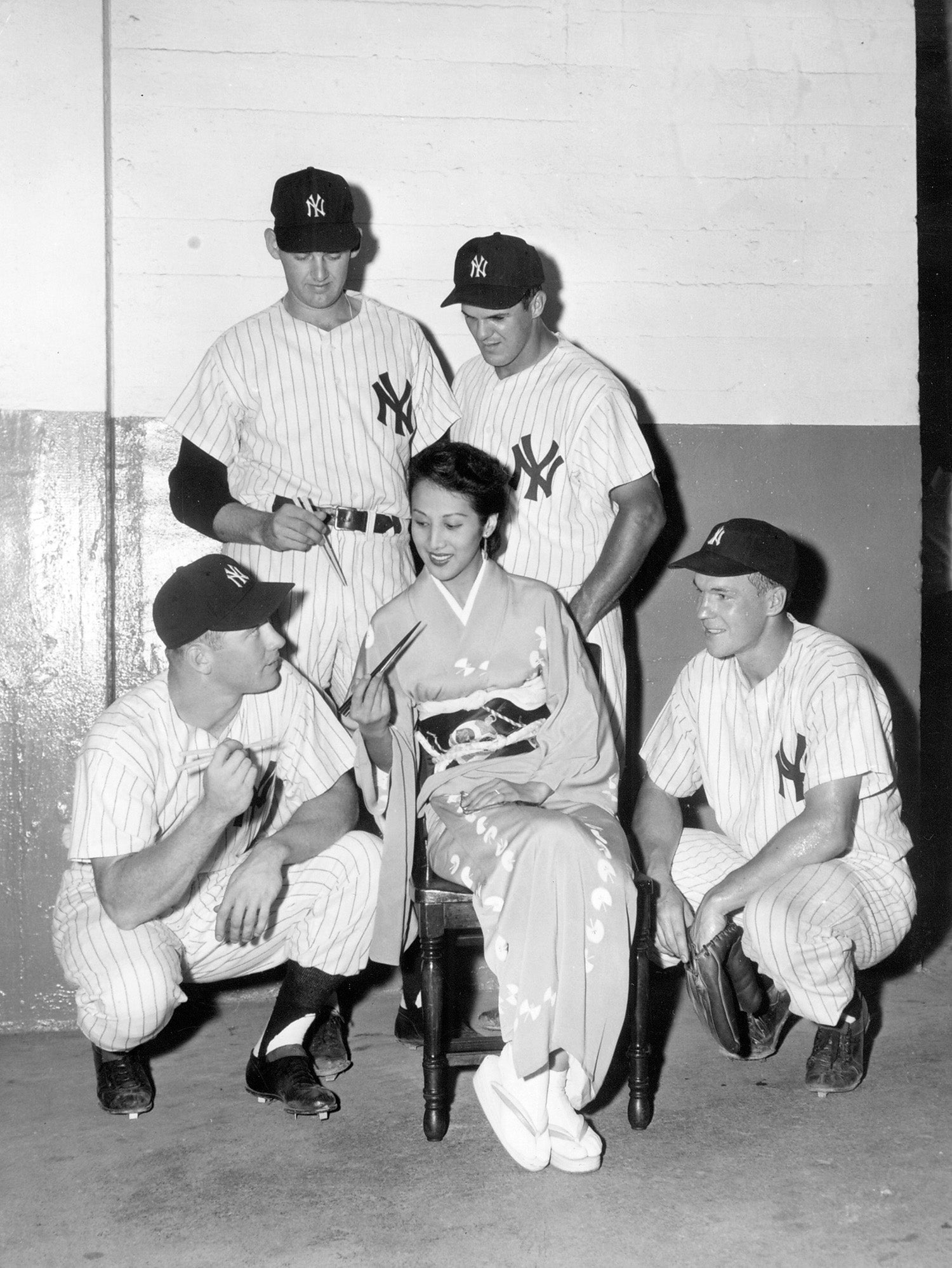

Sisler, who had been preparing to deploy when the Armistice was signed, was honorably discharged from the Gas & Flame Division and returned to the Browns, where he established himself as one of the game’s greatest hitters. His 257 hits in 1920 stood as the most in a single season for 84 years. In 1922, he set a record for a consecutive-game hitting streak, reaching safely in 41 games, and finished the season with a .420 average. A lifetime .340 hitter, Sisler was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939.

Cobb came back to the United States on the first ship out of France, arriving in Hoboken, N.J., on Dec. 17. Still coughing up fluid from the drill gone bad and feeling lousy, he announced his retirement from baseball.

He changed his mind once he started to feel better and the 1919 season approached. The 32-year-old Cobb returned to the Tigers, won his 12th and final batting title with a .384 average and played another 10 seasons before retiring for real in 1928 at age 41 with a .366 lifetime average, which remains the highest of all-time. He joined Mathewson in the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s first class.

Mathewson had written Reds owner Garry Herrmann that he would be returning in time for the 1919 campaign, but Hermann had not received his letter and hired a replacement. So Mathewson accepted a position as assistant manager under John McGraw with the team he had starred for as a pitcher, the New York Giants. But a cough that had stricken him after the botched gas-mask drill continued to dog him. His fading health forced him to retire from baseball after the 1920 season.

Doctors examined him in 1921 and diagnosed him with tuberculosis. The disease had killed his brother in 1917, and it is possible that Mathewson had been exposed to it through him. It is also possible that the mustard gas he had inhaled had weakened his respiratory system, making him more vulnerable to contracting the disease.

He was sent to the tuberculosis sanitarium in the Adirondacks mountain village of Saranac Lake, N.Y., where he was not expected to live more than six weeks.

Mathewson spent two years convalescing and felt strong enough to return to baseball in February 1923 when Emil Fuchs, the new owner of the Boston Braves, named him president of the team. His physicians cautioned Matthewson not to work himself too hard. But he did not know any other way. In the spring of 1925, he caught a cold he couldn’t shake, and his cough returned. He went back to Saranac Lake to recuperate.

In September, it looked like Mathewson might be improving, but then he took a turn for the worse and on Oct. 7, the first day of the 1925 World Series played between the Pittsburgh Pirates and Washington Senators, Mathewson died at the age of 45. The official cause of death was tuberculosis penumonia.

The following day, before the second game of the World Series, players from the Pirates and Senators wore black armbands to honor Mathewson. The 44,000 fans at Forbes Field stood while the flag was lowered to half-mast and all sang “Nearer My God to Thee.”

Cobb attended Mathewson’s funeral two days later in Lewiston, Pa. The Pennsyvlvania native was laid to rest in a cemetery next to his alma mater, Bucknell University, where Mathewson had starred for both the football and baseball teams.

“(He) looked peaceful in that coffin,” Cobb said. “That damned gas got him and nearly got me.”

John Rosengren is a freelance writer from Minneapolis