- Home

- Our Stories

- Long after his Hall of Fame induction, Jackie Robinson was making history

Long after his Hall of Fame induction, Jackie Robinson was making history

Five years after his Hall of Fame induction, Jackie Robinson returned to the Cooperstown area – this time addressing some of society’s challenges.

The year was 1967, a tumultuous time in America marked by social and political unrest, including the Civil Rights movement, protests against the Vietnam War, urban riots and the Summer of Love.

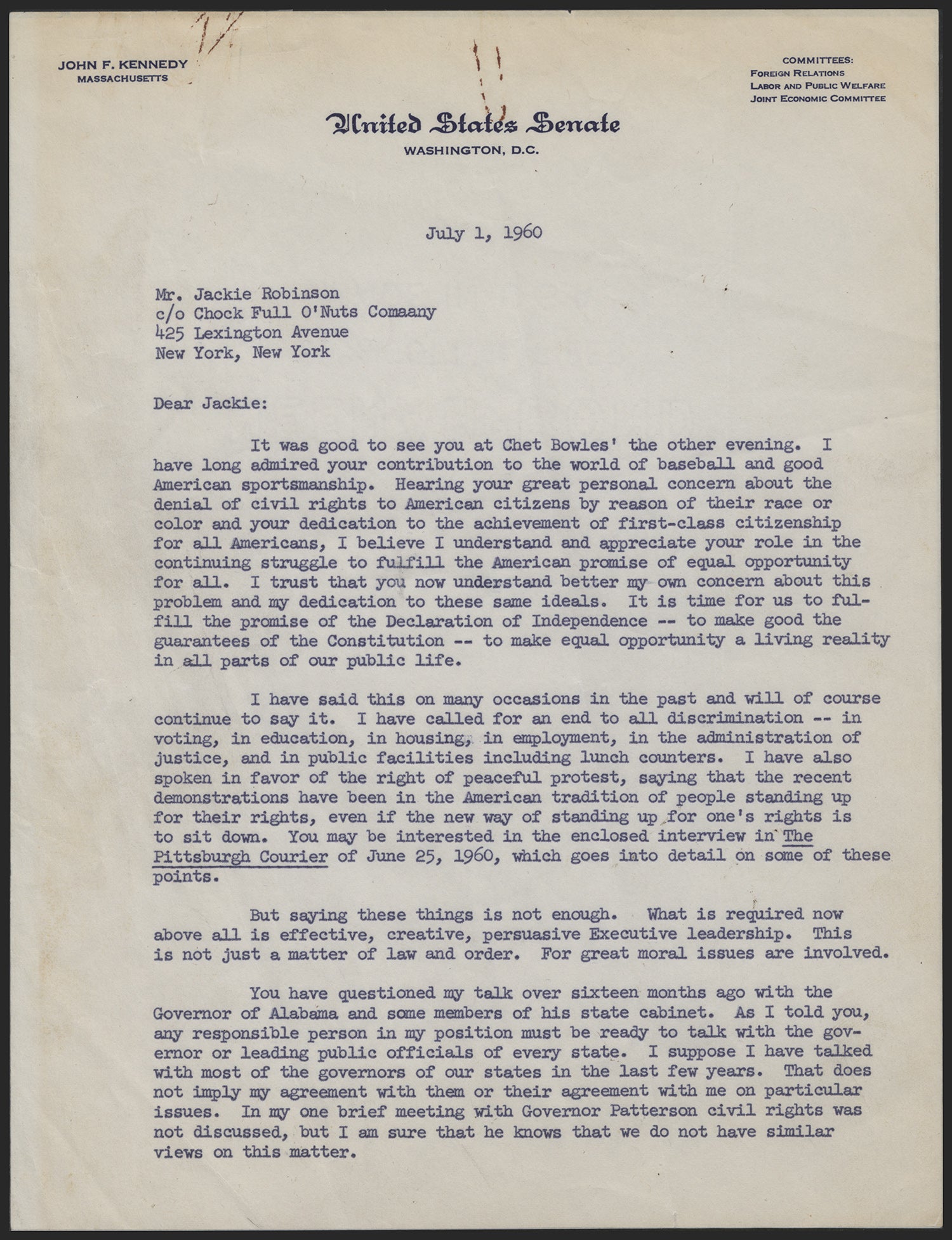

Robinson, a member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Class of 1962, famously broke baseball’s color line in 1947 with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

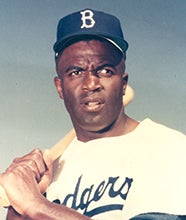

It was with this backdrop that Robinson arrived in Oneonta, N.Y., about a 30-minute drive south of Cooperstown, to speak at Hartwick College on May 9, 1967. But instead of spending time on the National Pastime, he viewed this as an opportunity to speak on the issues of the day.

Robinson, 48, had resigned as vice president in charge of personnel of Chock Full o’Nuts – a coffee and restaurant chain – in 1964 to work for New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller in his campaign for the Republican Presidential nomination. By 1967, he was Special Assistant to Governor Rockefeller for Community Affairs.

Referring to his job as an aide to the governor, Robinson said, “I wouldn't do it for anyone else.”

Robinson was invited to address a Hartwick convocation at the college fieldhouse before an audience of approximately 250, which included the student body, the general public and Hall of Fame Director Ken Smith as guests of the senior class. Prior to his address, he attended an Honors Day dinner and afterwards a public coffee hour and reception.

“Jackie Robinson’s visit to Hartwick College in 1967 was an extraordinary moment in our history,” said Hartwick College President James H. Mullen, Jr. in a recent statement. “It was an honor and privilege to welcome a man whose impact extended far beyond the baseball diamond.

“As a trailblazer who shattered barriers, he challenged us to think deeply about our role in society and our responsibility in meeting social needs. His message then remains relevant today, inspiring Hartwick students to lead with courage, integrity and purpose."

The Oneonta Star, after Robinson’s local appearance, referred to him as “an intelligent, articulate voice for the moderates in the Civil Rights movement. He is outspoken but dignified, concerned yet patriotic, polished yet capable of fighting hard if necessary.

“Robinson, unlike many contemporary headline-makers, does not duck tough questions. The tall, husky and very graceful ex-athlete looks his questioners in the eye and to the best of his ability (which is considerable) answers the question. He almost always prefaced his answers with, ‘well, in my opinion…’ not out of conceit, but to stress the thoughts were his and not that of any political or civil group.”

On the Civil Rights situation, Robinson told reporters the movement has encountered problems with “projections on the wrong people.”

“He has no following,” said Robinson, referring to Black activist Stokely Carmichael. “All he’s going to do is elect a Maddox (Georgia Governor Lester Maddox) or project a Wallace (former Alabama Governor George Wallace).”

Regarding Muhammad Ali – who less than two weeks before was stripped of his heavyweight title for refusing induction into the miliary – Robinson said the heavyweight boxer was receiving poor advice.

“The only people who will benefit from what he is doing are his lawyers,” Robinson declared, adding he admires Ali, “but I can’t go along with him on this issue because I feel strongly we can’t select what we want to do.

“(Ali) is going to jail, no ifs ands or buts about it. He has to be made an example of.”

Robinson also talked of his son Jack’s upcoming return from Vietnam, where he was an infantryman.

“My only problem is they have thousands of Negro troops in Vietnam and when they’re released, they’re subject to persecution and bigotry,” Mr. Robinson asserted. “The Southern traditions still exist.”

And while he added he has great respect and admiration for Dr. Martin Luther King, he cannot agree with him on his referring to the American government as “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.”

Stated Robinson: “Any cessation of the offensive we have mounted would only mean a respite during which the enemy could build its strength. We can win the (Vietnam) war, but it will be a long, hard struggle – one which we could not halt without cooperation and accord with the other side.”

Robinson also praised President Johnson, saying he is “the greatest ally we have – an ally who has exceeded my great expectation on what he would do for the Negro.”

Before Robinson left, he joked with those in attendance, “Have you ever tried to fly by commercial airliner from Oneonta to Regina, Saskatchewan, and then to New York?”

Wrote the Oneonta Star the next day: “He came to Oneonta and Hartwick College a great athlete of an era in which many of the Hartwick students had not yet been born.

“He left a great voice in a movement toward equality for his race and the effects of his visit will linger for many months.”

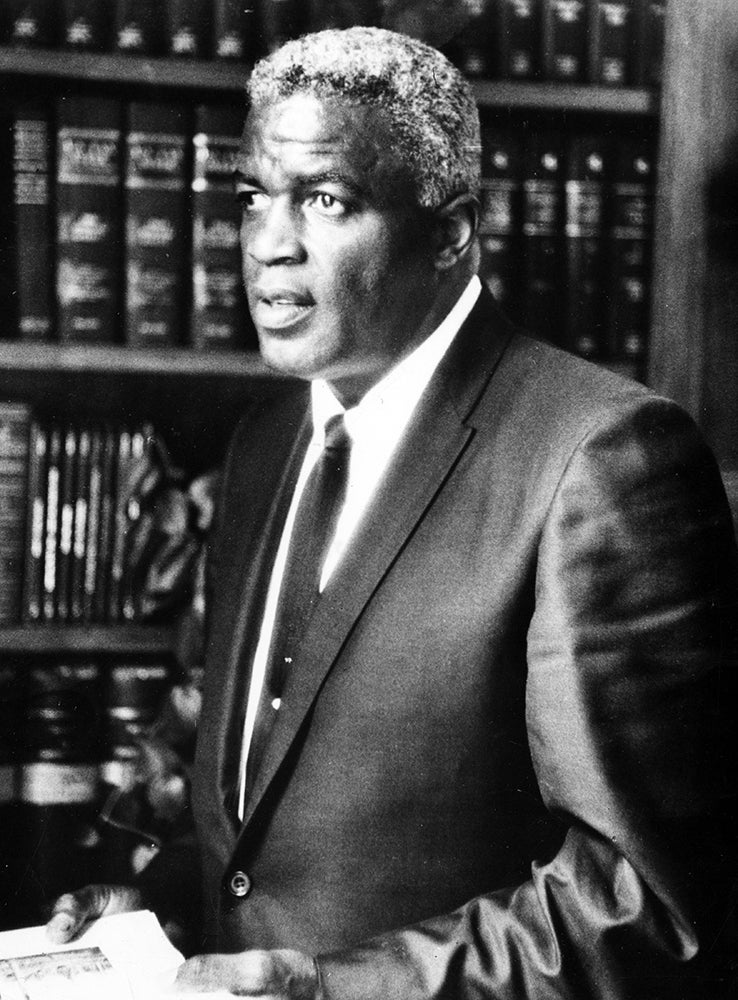

The Jackie Robinson of 1967 was active in civil rights work as well as serving as president of the Gibraltar Life Insurance Company. He also went to Buffalo attempting to stem days of racial violence, refuted rumors of running for a senate seat in Connecticut in 1968, lent his name to the new Jackie Robinson Brooklyn North Police Baseball League and backed an Olympic boycott by Black athletes.

He also penned a syndicated weekly newspaper column, “Jack Robinson Says,” where he shared his thoughts on a wide variety of issues, including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., big league baseball ignoring its former Black stars, opportunities to help young people, the war on poverty, and President Lyndon B. Johnson and Vietnam.

“But I do know that I shall continue to write and say what I believe,” is how Robinson ended one column. “I don’t seek to be anyone’s martyr or hero, but telling it like I think it is – that’s the only way I know how to be me.”

Robinson would pass away five years later, on Oct. 24, 1972, at the age of 53.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum