“I don’t think it would have mattered who we played. That might have been the best team ever assembled.”

- Home

- Our Stories

- Mays-Newcombe barnstorming tour of 1955 set records, broke barriers

Mays-Newcombe barnstorming tour of 1955 set records, broke barriers

On Oct. 16, 1955, Asheville Citizen Times reporter Mal Mallette arrived at McCormick Field for what should’ve been a relatively routine assignment. Mallette was tasked with a story on an upcoming exhibition game between Sherm Lollar’s barnstorming All-Stars and a local team based in Buncombe County.

What he found instead was a stadium filled to one-fifth of its capacity, and a very unamused Gene Woodling. “I’m sure glad we’re working mostly on guarantees, or else we wouldn’t make enough to buy peanuts,” quipped the Cleveland Indians’ left fielder. “We haven’t had but a couple of good crowds. In the two places where we were working on a percentage basis, I think our takes were eight and 40 dollars.”

Hoping for higher attendance in Greensboro, the All-Stars took their chances against the Carolina League All-Stars. They lost, in front of a crowd of 221. In response, sportswriter Earle Hellen of the Greensboro Record proclaimed that “barnstorming’s dead around here.”

Hellen’s statement might’ve held true, if the “Say Hey” Kid hadn’t come to town. A mere two days after Lollar’s All-Stars played in McCormick, the Mays-Newcombe All-Stars took the field, nearly packing the ballpark.

“Here we have evidence that there is still gold in the hinterlands if you have the right troupe,” wrote Mallette. “Mays and Newcombe, naturally, have been drawing a large number of Negro fans as could be expected. But that is only part of the magic. Mainly they’re drawing because Mays and Newcombe have just finished good season and the fans want to take a look. The lesson to be learned from the current tours is: If you don’t have a big star for top billing, get a guarantee.”

With all due respect to Mallette, classifying 1955 as a “good season” for the All-Stars was a bit of an understatement – on multiple fronts. Don Newcombe finished the year with a record of 20-5 for the Dodgers and the Giants’ Willie Mays had led the National League in homers with 51. The Cubs’ Ernie Banks was coming off a season in which he hit five grand slams (an MLB record) and Banks’ teammate Sam Jones had tossed a no-hitter. And of course, we can’t forget 21-year old Hank Aaron, who had hit 37 doubles, posting a slash line of .314/.366/.540 with a .906 OPS in his second full season with the Braves.

Seems like a pretty incredible group, right? Well, believe it or not, those numbers and names only scratched the surface. The Mays-Newcombe All-Stars had four Hall of Famers just among its outfielders. Roy Campanella was behind the plate, Jones, Newcombe, Brooks Lawrence and Joe Black were on the mound, while Junior Gilliam and George Crowe manned the infield. It was basically the best team in baseball – with most of its players at the prime of their careers.

“I don’t think it would have mattered who we played,” Mays said in his biography. “That might have been the best team ever assembled.”

Traveling by car across the South and to the West Coast, the All-Stars went 28-0 that winter, facing Negro League teams in a 25-city tour. Organized by Curtis A. Leake, a traveling secretary, and Mays himself, the team drew 20,000 fans in their first five games, and more than 100,000 overall.

But barnstorming was nothing new to baseball, and was certainly nothing new to Willie Mays.

“What’s barnstorming?!” Mays said to the New York Times, in disbelief. “Barnstorming was when you put together a team after the season and went around the country playing wherever you could get paid. Jackie Robinson had a team with Larry Doby and Pee Wee Reese and Gil Hodges that we played in Birmingham back when I was 15 years old. I made $500 a month playing in the Black leagues before the Giants signed me. I had to take a cut when I went to play (Class) B ball in the minors. My first few years, I made more money barnstorming than I did with the Giants.”

Willie had been touring since he was a teenager, but 1955 marked the first year that he would co-pilot a team bearing his name. He didn’t disappoint.

On Oct. 27 in Longview, Texas, so many fans entered the ballpark that the game was delayed 25 minutes. He rewarded their patience by hitting a single, a triple and a homer. In Atlanta, he hit one of the longest homers in the history of Ponce de Leon Park – 460 feet, right over the center field wall.

“Willie was playing his usual reckless game, and Monte reminded him to take it easy, that his career with the Giants was more important,” Ernie Banks said in Willie Mays: The Life, the Legend. “Willie said, ‘This is the only way I can play.’” Mays wasn’t the only one who shined. In Little Rock, Ark., Aaron went 4-for-5 – with all of his hits home runs. In El Dorado, Ark., Black and Lawrence combined for a near-perfect game, Black recording eight whiffs, and Lawrence six. They allowed only one hit. And on Nov. 12, the team beat the Negro American League All-Stars 20-1, as Newcombe played six innings in right field to rest his arm.

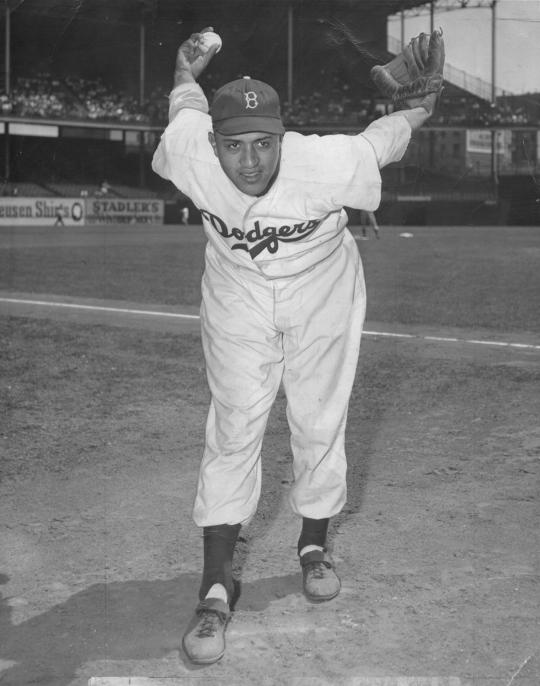

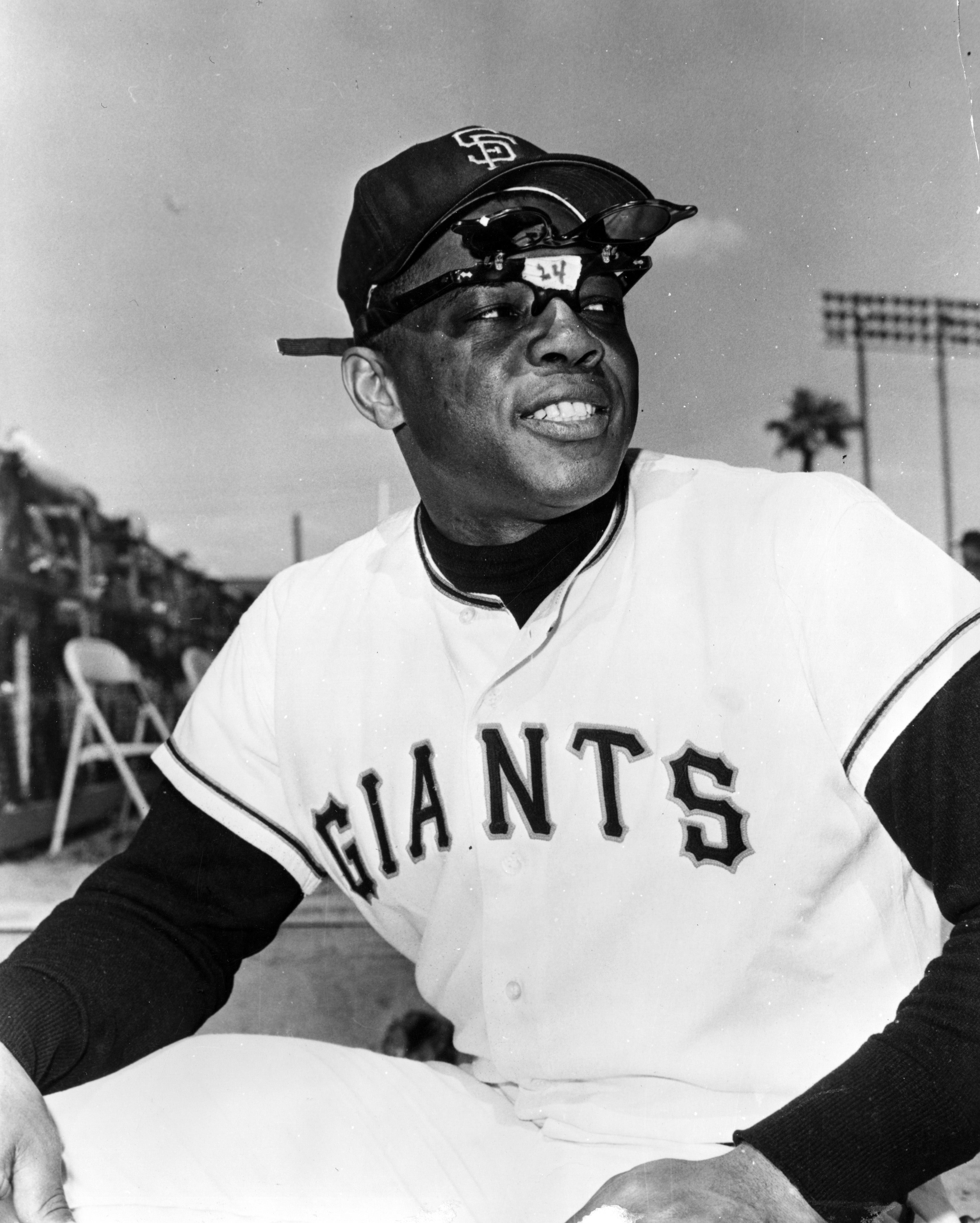

In 1955, the Dodgers' Don Newcombe (pictured above) posted a record of 20-5. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

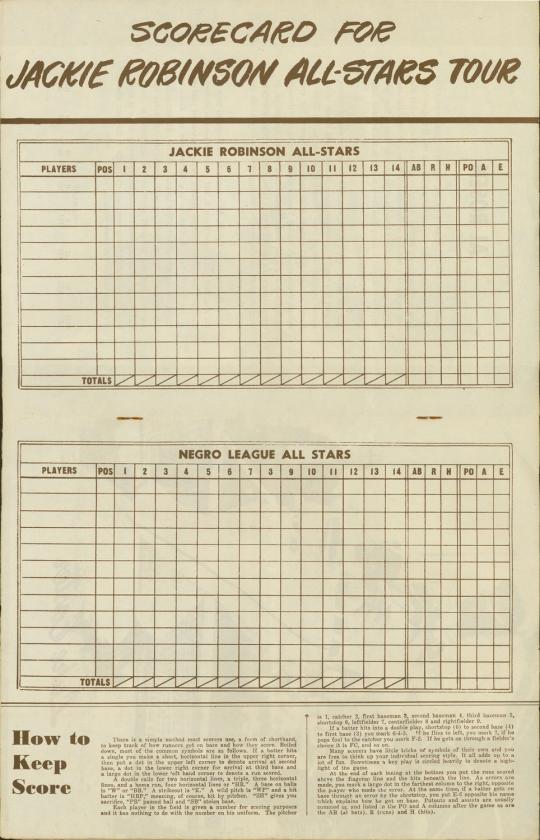

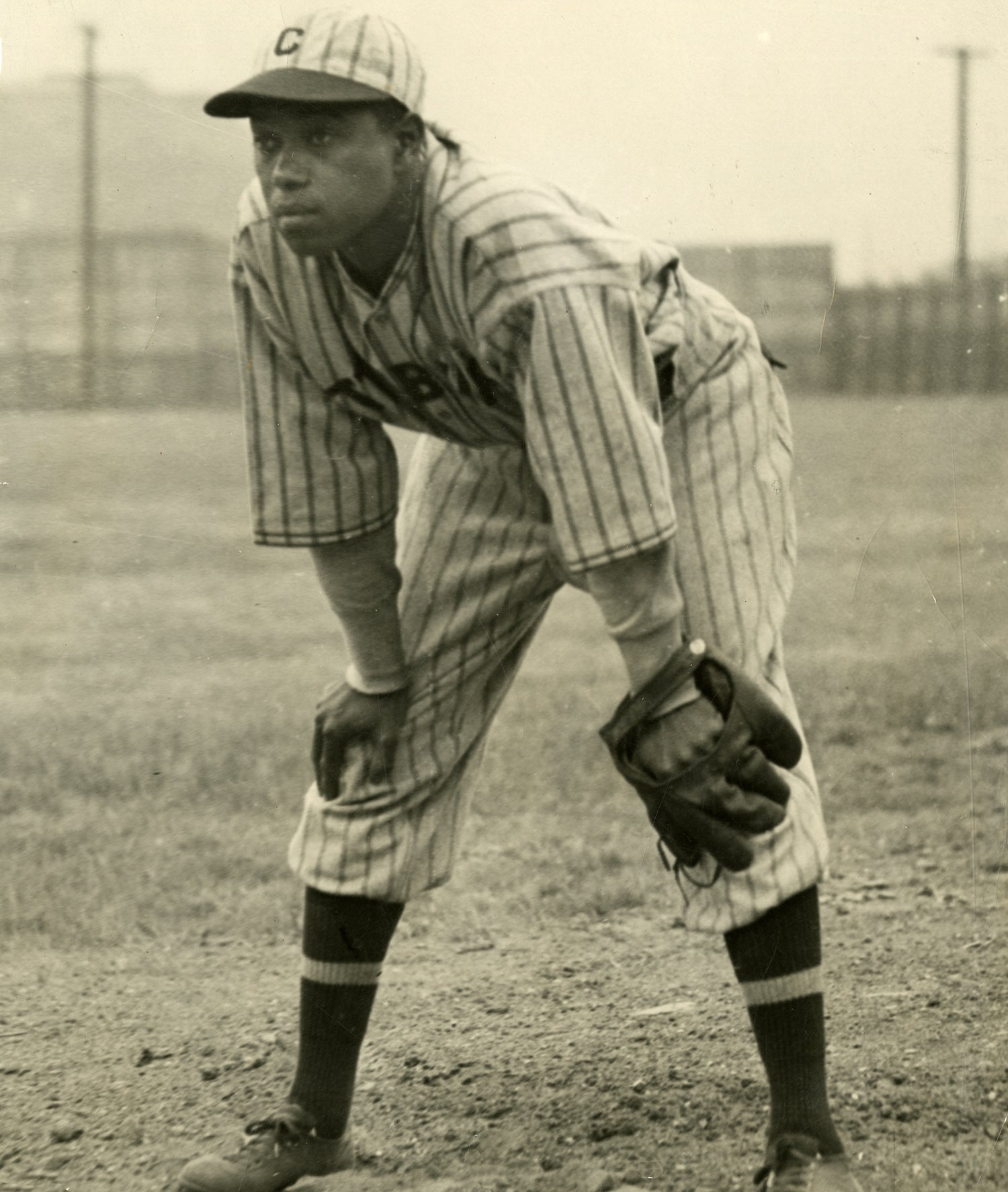

This scorecard was printed ahead of a 1953 exhibition game in which the Jackie Robinson All-Stars faced off against the Negro League All-Stars. Postseason barnstorming tours were common from baseball’s earliest days through the 1950s. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

But for all the success that the Mays-Newcombe All-Stars had, the historical context in which they had it renders their feats even more impressive. They were in Little Rock only two years before nine Black students integrated the city's local high school. They played in Montgomery 10 years before Bloody Sunday took place on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. And they visited Birmingham eight years before the 16th street Baptist church bombing.

Seventeen adult Black men were touring the country at a time when racial tension was reaching unprecedented heights. Despite the ease with which they reached 28-0, their experiences off the field were anything but easy. Yet as so many had before - and would continue to after - they pushed forward with their heads held high, giving fans a glimpse of greatness, every stop along the way.

Negro League third baseman Judy Johnson may have said it best, when in an interview he recalled a season in which he hit .392.

“The owner gave me a ten dollar raise, but we played for something greater that couldn't be measured in dollars and cents. The secret of our game was to enjoy and endure."

Alex Coffey was the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum