- Home

- Our Stories

- Scientists explored secrets behind Ruth’s epic 1921 season

Scientists explored secrets behind Ruth’s epic 1921 season

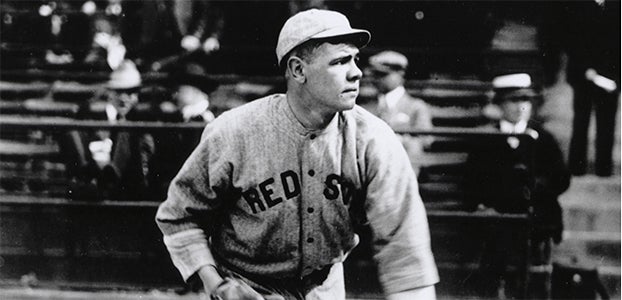

One-hundred years ago, Babe Ruth, in the midst of arguably the greatest offensive season any ballplayer has ever enjoyed, spent more than three hours being tested by a pair of psychology researchers to discover the source of his superiority.

Their conclusion? As most American League pitchers knew at the time, Ruth, compared to the average man, was both physically and mentally exceptional.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Yankees Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

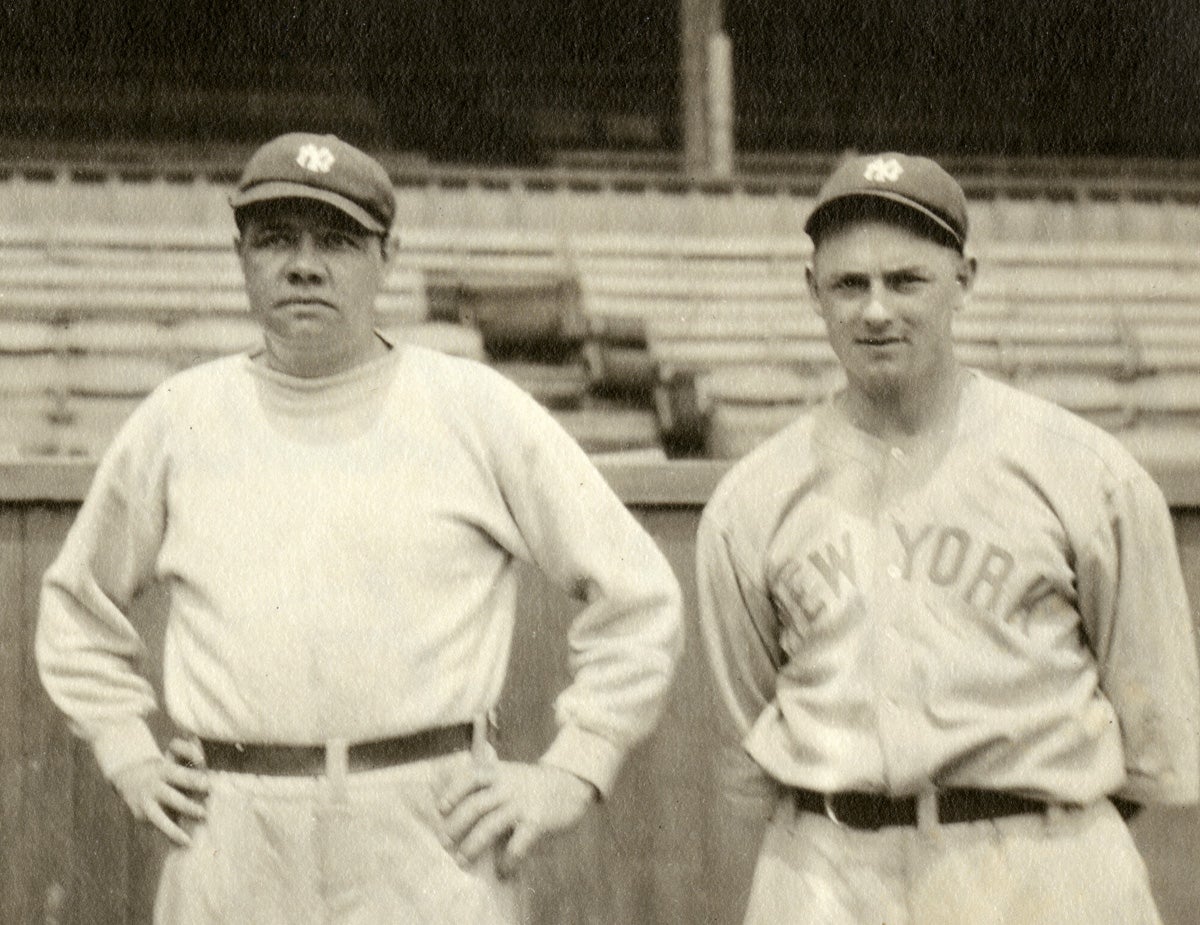

In 1921, the 26-year-old Ruth – the former southpaw hurler then a slugging outfielder with the New York Yankees – walloped 59 home runs, setting a new major league single-season record for the third consecutive year. He also led big league baseball with 168 RBI, 177 runs scored, 145 walks, a .512 OBP, and a .846 slugging percentage, and his 457 total bases and 119 extra base hits remain big league records. And the only reason he didn’t win the MVP Award was because the sport was in a period where they weren’t being presented.

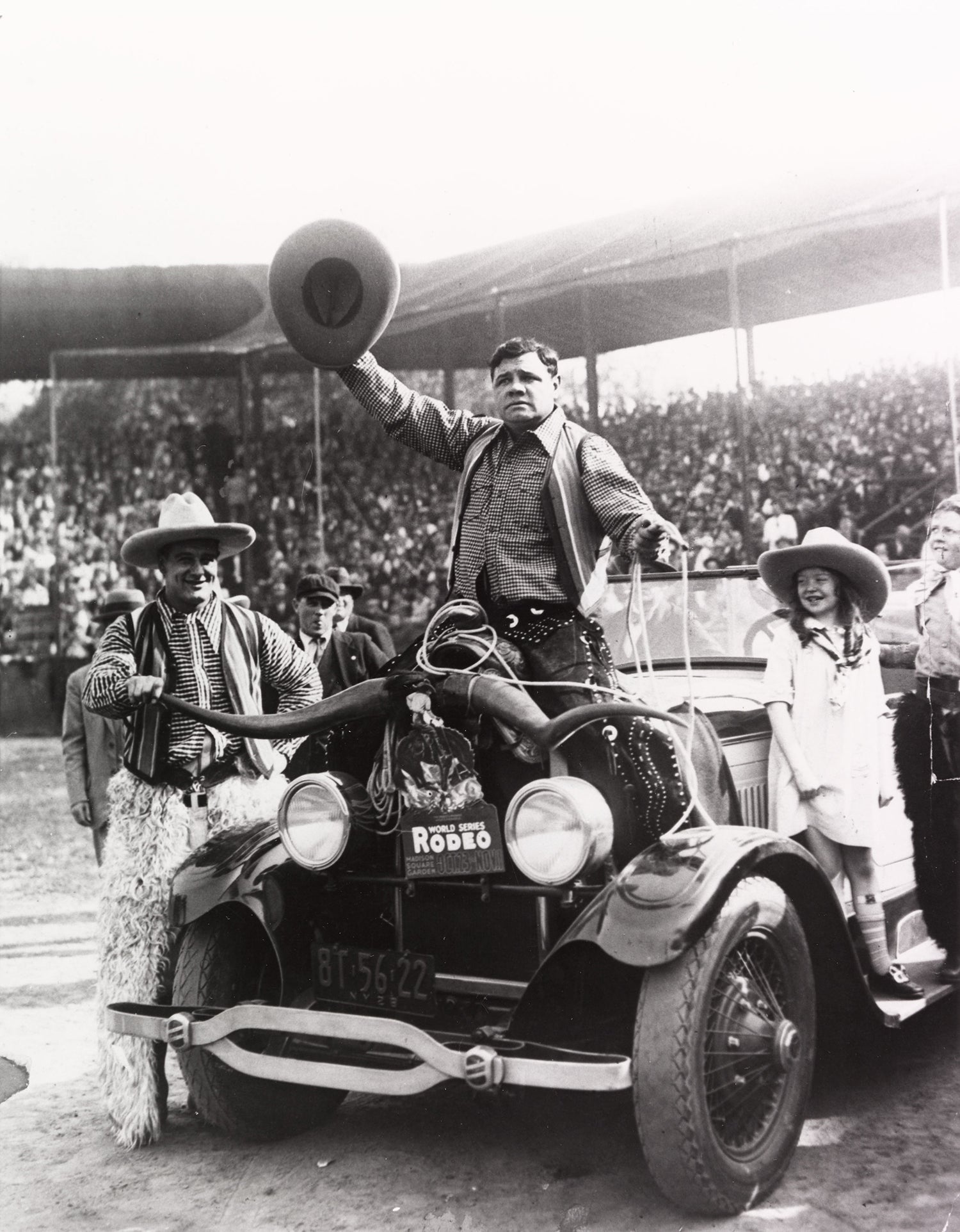

This was the “Roaring Twenties” as well as the “Golden Age of Sports” and Ruth, with his childlike enthusiasm and hard-to-resist charisma, was its human embodiment. Newspapers, of which there was more than a dozen in New York City, seemed to document his every move.

So when word spread in early September that this diamond hero had visited a college’s psychology department to ascertain the secret of his greatness, it not only made news in the Big Apple but around the country. It even ran on the front page – above the fold – of The New York Times.

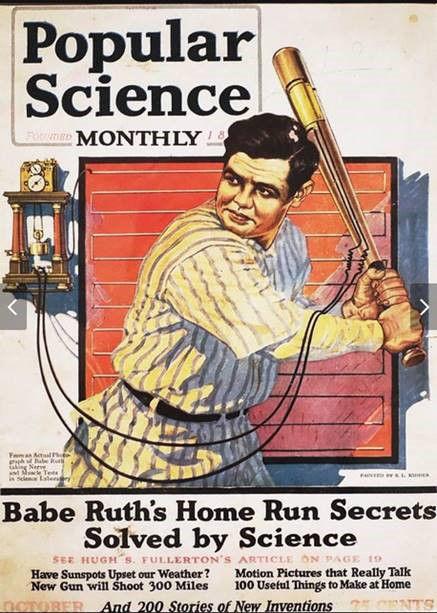

The source of the hoopla was the October 1921 edition of Popular Science Monthly. For 25 cents, a reader could check out the magazine’s cover story, “Babe Ruth’s Home Run Secrets Solved by Science,” as well “Have Sunspots Upset our Weather,” “New Gun will Shoot 300 Miles,” “Motion Pictures that Really Talk,” and “100 Useful Things to Make at Home.”

Authoring the Ruth exclusive was Hugh Fullerton, the sports editor of New York’s The Evening Mail and the 1964 recipient of the BBWAA’s prestigious Career Excellence Award for “meritorious contributions to baseball writing.”

The four-page, 2,500-word article, populated with five images of Ruth undergoing testing, was promoted by Popular Science Monthly with advertisements in newspapers across the country with the headline, “Babe Ruth astounds scientists.”

Prior to the start of the 1921 campaign, catcher Pinch Thomas, a former teammate of Ruth’s in Boston, aptly explained the phenomena.

“I told some of the fellows this spring that Babe Ruth would hit 40 home runs before the season ended,” he told Baseball Magazine. “They laughed at me and what is more offered to bet. I wish now I had taken them up, but I got to thinking it over and concluded that 40 home runs was quite a contract.

“Besides, Babe Ruth is only human and might slump. But I am not so certain now that Babe is human. At least, he does things which you couldn't expect a mere batter with two arms and legs to do. I can't explain him. Nobody can explain him. He just exists.”

According to Fullerton, after a game at the Polo Grounds – the home ballpark of the Yankees in 1921 – Ruth, still wearing his home uniform after homering that day, traveled to nearby Columbia University’s Psychological Research Laboratory.

“The game was over. Babe, who had made one of his famous drives that day, was tired and wanted to go home,” Fullerton’s story began. “’Not tonight, Babe,’ I said. ‘Tonight you go to college with me. You're going to take scientific tests which will reveal your secret.’

“’Who wants to know it?’ asked Babe.

“’I want to know it,’ I replied, ‘and so do several hundred thousand fans. We want to know why it is that one man has achieved a unique batting skill like yours – just why you can slam the ball as nobody else in the world can.’”

Ruth was in the hands of Columbia’s Albert Johanson and Joseph Holmes to undergo a series of tests. Holmes grew up in Oneonta, N.Y., only 20 miles from Cooperstown.

“They led Babe Ruth into the great laboratory of the university,” wrote Fullerton, “figuratively took him apart, watched the wheels go round; analyzed his brain, his eye, his ear, his muscles; studied how these worked together; reassembled him, and announced the exact reasons for his supremacy as a batter and a ballplayer.”

Machines, considered complex at the time but undoubtedly primitive by today's standards, were used to evaluate Ruth.

Ultimately, the tests proved that Ruth is 90 percent efficient as against the human average of 60; that his eyes are 12 percent faster than the ordinary man’s; that his ears function 10 percent faster than the average; that his nerves are steadier than 499 out of 500 persons; that he’s 1½ times the average in attention and quickness of perception.

“The tests used were ones that primarily test motor functions and give a measure of the integrity of the psychophysical organism. Babe Ruth was posed first in an apparatus created to determine the strength, quickness, and approximate power of the swing of his bat against his ball,” Fullerton wrote. “A plane covered with electrically charges wires, strung horizontally, was placed behind him and a ball was hung over the theoretical plate, so that it could be suspended at any desired height.

“I learned something then which, perhaps, will interest the American League pitchers more than it will the scientists. This was that the ball Ruth likes best to hit, and can hit hardest, is a low ball pitched just above his knees on the outside corner of the plate. The scientists did not consider this of extreme importance in their calculations, but the pitchers will probably find it of great scientific interest.”

The psychologists also discovered that Ruth did not breathe during his entire swing. They stated that if he kept breathing while swinging, he could generate even more power.

“The scientific ivory hunters of Columbia University discovered that the secret of Babe Ruth's batting, reduced to non-scientific terms, is that his eyes and ears function more rapidly than those of other players; that his brain records sensations more quickly and transmits its orders to the muscles much faster than does that of the average man,” Fullerton wrote.

“The tests proved that the coordination of eye, brain, nerve system, and muscle is practically perfect, and that the reason he did not acquire his great batting power before the sudden burst at the beginning of the baseball season of 1920, was because, prior to that time, pitching and studying batters disturbed his almost perfect coordination.”

After detailed explanation of the testing process, Fullerton ended his Popular Science Monthly piece trumpeting the discovered explanation of Ruth’s diamond superiority.

“The secret of Babe Ruth's ability to hit is clearly revealed in these tests,” Fullerton wrote. “His eye, his ear, his brain, his nerves all function more rapidly than do those of the average person. Further the coordination between eye, ear, brain, and muscle is much nearer perfection than that of the normal healthy man.

“The scientific ‘ivory hunters’ dissecting the ‘home-run king’ discovered brain instead of bone, and showed how little mere luck, or even mere hitting strength, has to do with Ruth's phenomenal record.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum