- Home

- Our Stories

- In 1916, the Babe began a historic streak on the mound

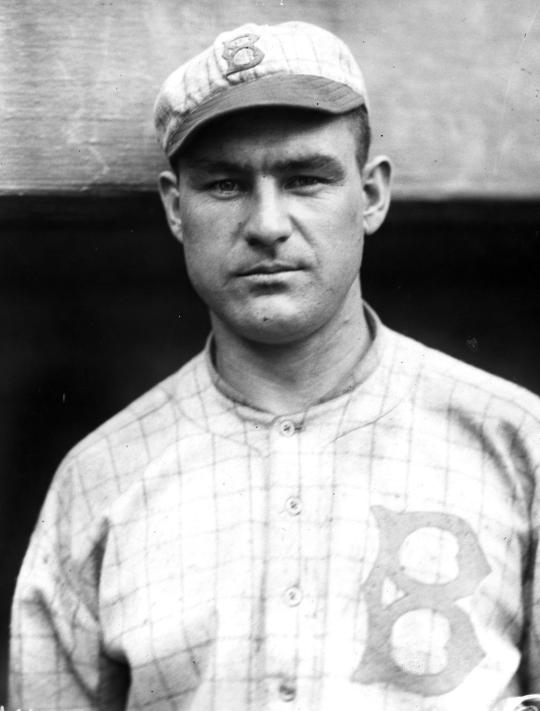

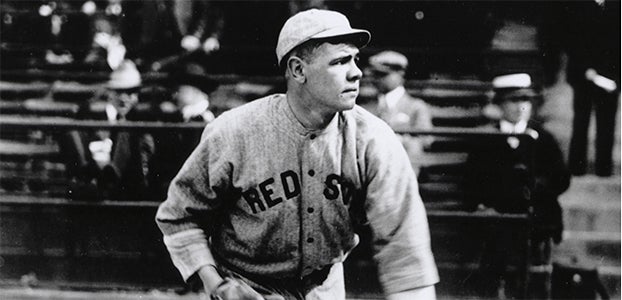

In 1916, the Babe began a historic streak on the mound

With two down in the top of the first inning on Oct. 9, 1916, Brooklyn’s Hi Myers blasted the ball deep into Braves Field’s cavernous right-center field, reaching the fence about 400 feet away.

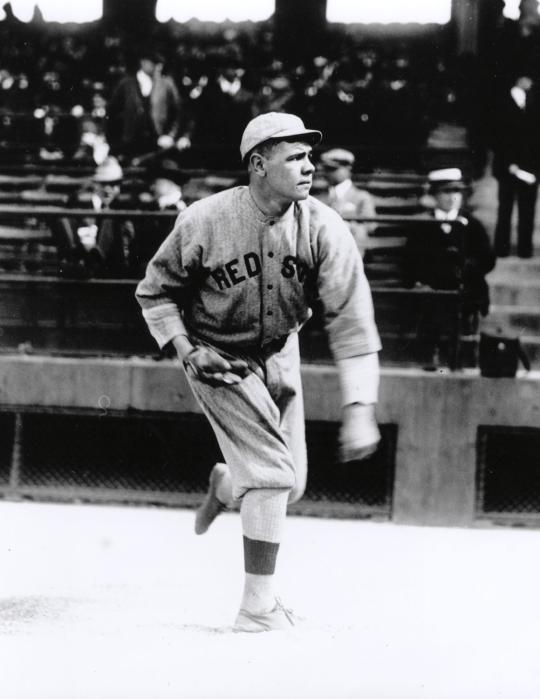

After watching Myers slide head-first into home plate with an inside-the-park home run, Red Sox hurler Babe Ruth dusted himself off and settled in for the next 13.1 innings. It would be the last run he would allow that day.

And – in the World Series – it would be the last he’d allow for the next 23 months.

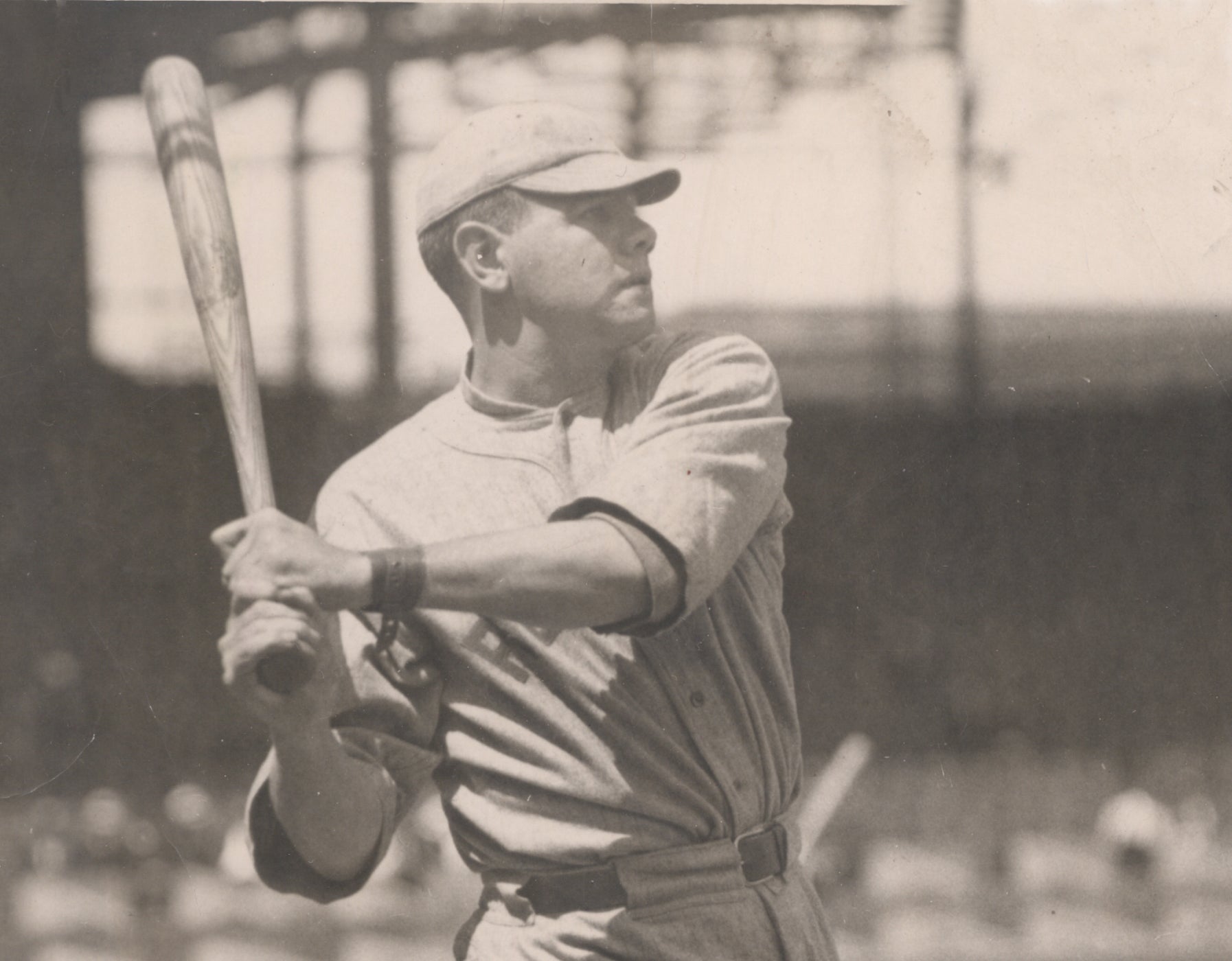

It all started a century ago, as the man who would become one of the game’s greatest hitters was authoring one of the game’s great pitching performances.

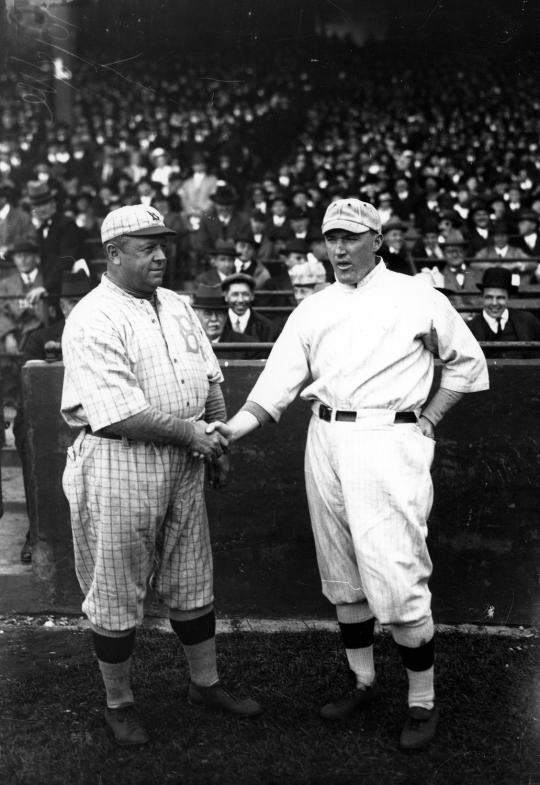

Boston took the second game of the 1916 World Series 2 to 1 in a tightly contested 14-inning duel between Ruth and Brooklyn’s Sherry Smith. The victory gave the Sox a two-games-to-none lead over Wilbert Robinson’s squad.

Normally the home field of Boston’s National Leaguers, Braves Field belonged to the Red Sox in the 1915 and 1916 Fall Classics. The larger seating capacity, compared to Fenway Park, enticed Sox ownership into renting the jewel box of a ballpark for baseball’s crown jewel event. Yet it still felt like home for Boston’s junior circuit entry, as the Red Sox won all five postseason games played there those years.

Limited to a single pinch-hitting appearance in the 1915 World Series after a solid regular season – it has been said Boston wanted to use right-handed pitchers against the Phillies – Ruth used the following year’s campaign as a coming out party of sorts.

Dominant over American League hitting during the 1916 regular season, Ruth stifled Brooklyn in his only postseason appearance that year. He scattered six hits while striking out four and walking three. Robinson’s team nearly broke through with another run in the eighth inning, but that was prevented when Ruth tagged Mike Mowrey in a run down between third and home.

Defense and pitching were the names of this game, and Boston’s were just too much for the Dodgers to handle, according to the Boston Globe’s Grantland Rice.

“[F]or 14 innings this Boston defense formed a long, wide wall of steel and stone back of Babe Ruth,” he described. “And against this wall Brooklyn rebounded to her second defeat.”

Rice, however, was more inclined to deem Smith the more dominant pitcher in the match. He wrote:

Ruth got the decision, but for all that Smith pitched the better game. For 13 innings he had the Red Sox lashed to the Phantom Swing, as helpless as the bewildered old dame who attempted to sweep back the ocean with a porous mop. They couldn’t hit him with a machine gun loaded with buckshot. It was not until Wily William Carrigan rushed a total stranger into the quarrel that Smith toppled over into the gorge with his crown still on, but his kingdom conquered.

The “total stranger” Rice referred to was Del Gainer, whom Red Sox manager Bill Carrigan sent up to pinch hit for third baseman Larry Gardner. Gainer’s single to left field drove in pinch runner Mike McNally for the winning run in the 14th inning.

In the next day’s Boston Globe, a column by “Sportsman” listed notes and reactions to Game 2. Ruth, who finished the game with six no-hit innings, received plaudits, but Gainer was feted even more for his actions.

“‘Del’ Gainor (sic) is a real World’s Series HERO,” the column exclaimed. “You can’t keep a pinch hitter, who wins a game in the 14th inning, out of the baseball hall of fame.”

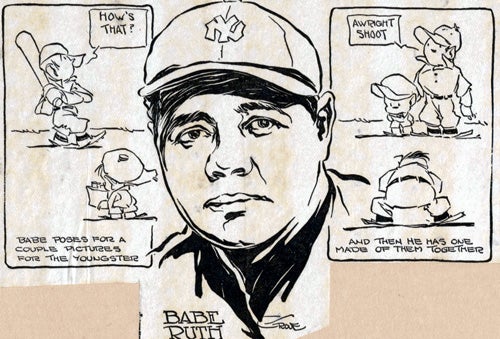

Gainor would never take a spot in the actual Baseball Hall of Fame, still nearly 20 years from fruition, and he would never so much as receive a single vote in the balloting. On the other hand, Ruth would become one of the first five elected to the baseball shrine.

Boston defeated Brooklyn in five games to win the 1916 World Series.

The Red Sox returned to the postseason two seasons later, the World Series being played in September, as the regular season was shortened due to World War I.

Ruth drew the mound assignment for the opener on Sept. 5 and defeated the Cubs 1-0 at Comiskey Park. With another nine frames under his belt, his scoreless streak grew to 22.1 innings.

Four days later, on Sept. 9, exactly 23 months after the streak began, Ruth took the hill again at Fenway Park and lasted 7.1 innings before Chicago came through with a pair of runs. The streak totaled 29.2 innings over three games.

Red Sox Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Ruth pitched generally well in Game 4 of the 1918 World Series despite nursing bruised a finger on his throwing hand acquired “during some sugarhouse fun with (Red Sox batting practice pitcher) W.W. Kinney,” the Boston Globe’s Edward F. Martin wrote, on the team’s train ride to Boston from Chicago.

Martin also noted that “[a]ll the world should know, Babe said, that it was not the finger that was troubling him, but the stuff that was on it, and the stuff that was on it was putting too much stuff on the ball.” The iodine may not have helped Ruth that afternoon, but it enhanced his entry in the record books.

The World Series scoreless innings pitched record held by Ruth would finally be broken in 1961 by Whitey Ford, who would then extend the mark in 1962 to 33.2 innings.

Whether anyone else will come close to or surpass Ruth or Ford remains to be seen. San Francisco’s Madison Bumgarner holds the highest streak among active pitchers. He went 21.2 consecutive scoreless innings through the 2010, 2012, and the first game of the 2014 World Series. After giving up a run in that game, Bumgarner then went on to pitch 14.1 scoreless innings – still an active streak – through the remainder of the 2014 Fall Classic.

Matt Rothenberg is the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum