- Home

- Our Stories

- Ford breaks Ruth’s World Series scoreless innings streak

Ford breaks Ruth’s World Series scoreless innings streak

Babe Ruth built his legendary Hall of Fame career from the strength of his bat. One of his longest-standing records, however, was set on the pitcher’s mound.

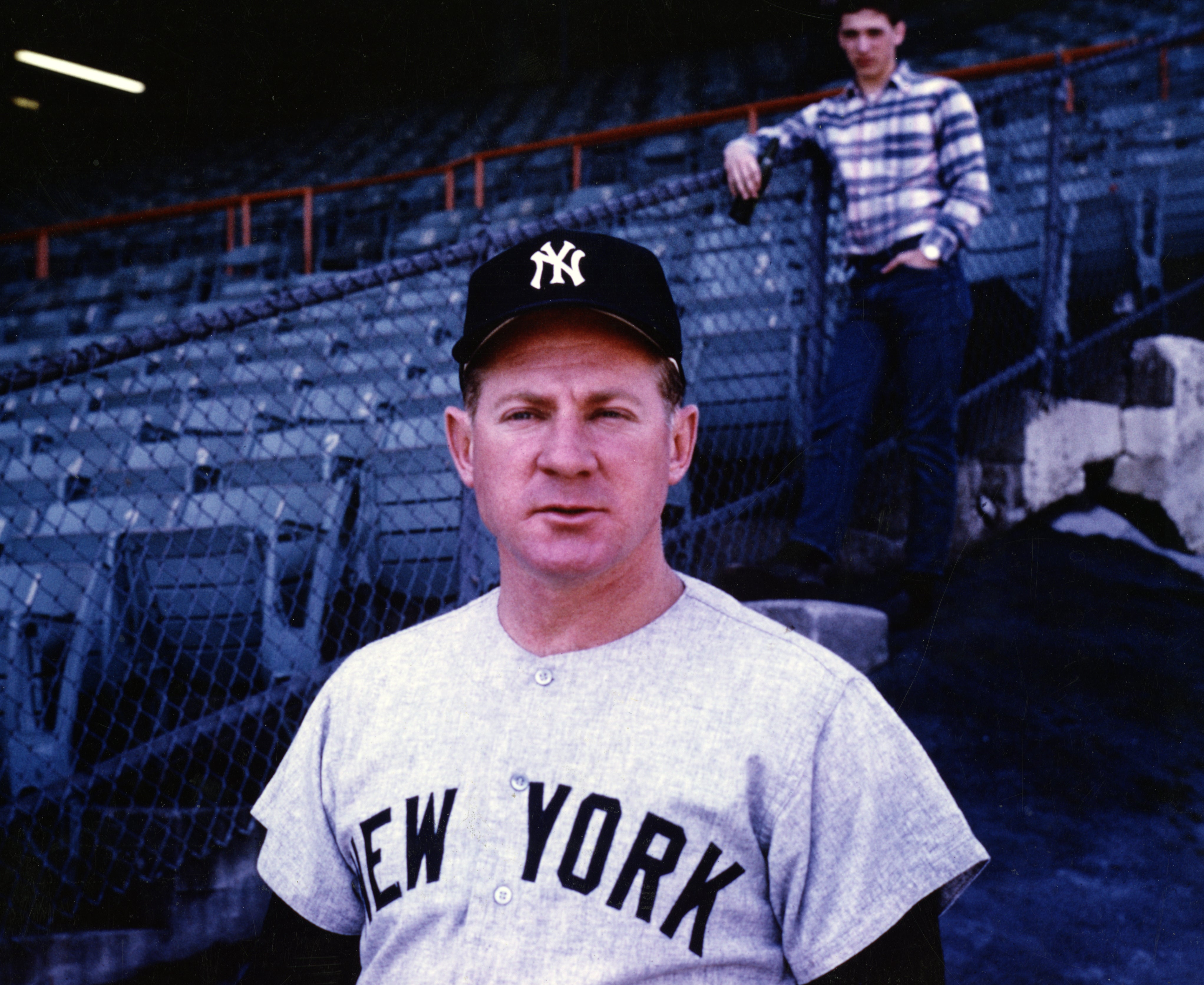

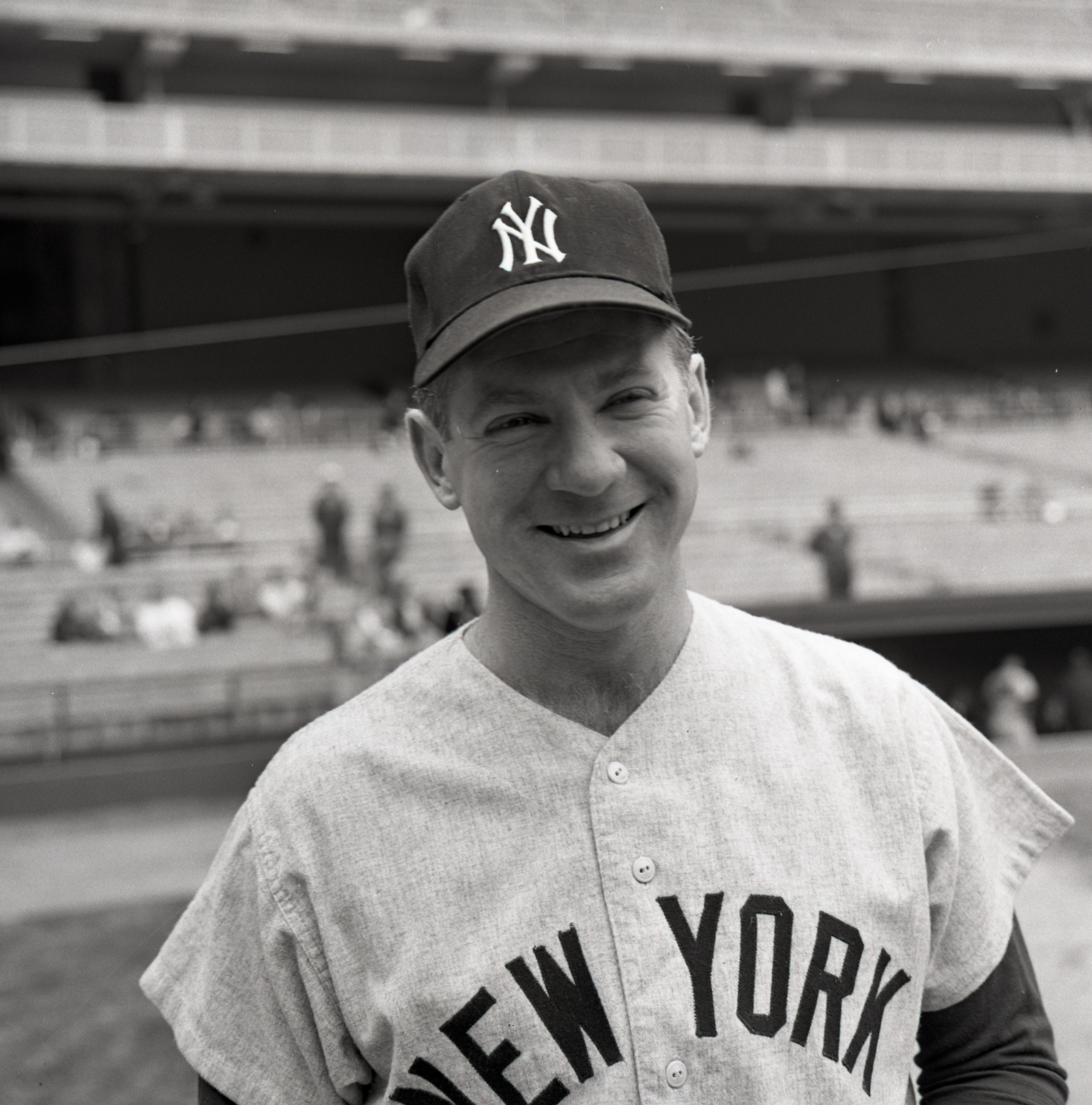

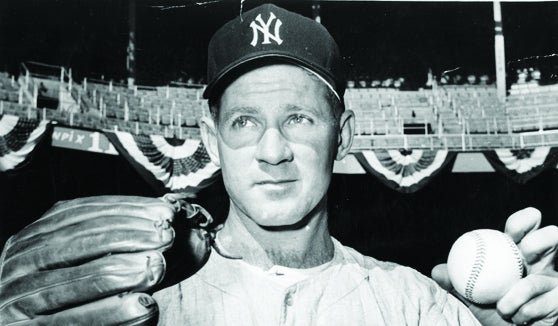

Before he became the Sultan of Swat, Ruth was considered one of baseball’s best left-handed pitchers. Ruth’s less-heralded prowess as a hurler was a surprise to another Yankees Hall of Famer, pitcher Whitey Ford.

“I had thought he was a lousy pitcher who they made into a hitter,” Ford told reporters in 1961. “I looked at the Baseball Encyclopedia one day and was stunned at what I found out.”

In the days leading up to Oct. 8, 1961, Whitey Ford was suddenly answering a lot of questions about Babe Ruth. That’s because Ford was on the doorstep of breaking Ruth’s record for pitching 29 2/3 consecutive scoreless innings in the World Series – a record the Babe had held for 43 years.

Just like the Bambino was synonymous with home runs, Ford was known for winning big games. Nicknamed “The Chairman of the Board” for the way he controlled the game, Ford won 236 games – the most wins in Yankees history.

When Ford retired from the game in 1967, he left as the standard-bearer in many World Series pitching categories. To this day, Ford still holds records for most wins (10), innings pitched (146), games started (22) and strikeouts (94) in the Fall Classic.

As a rookie in 1950, Whitey won nine games for the Yankees and lost just one. In Game 4 of the 1950 World Series, Ford showed his first flash of brilliance in high-pressure situations as he shut out the Philadelphia Phillies for the first eight innings. The Yankees won the game 5-2 to complete their Fall Classic sweep.

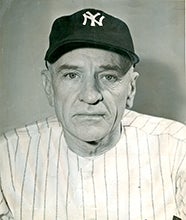

Yankees manager Casey Stengel was impressed with his rookie phenom after the 1950 season. “I never saw a kid with such good control for his age,” Stengel marveled. “You don’t find pitchers like him every day – and if you do please let me know where they are.”

As the ace of the great Yankees dynasties of the 1950s and 1960s, Ford was the hurler that the Bronx Bombers could always turn to. He was the team’s Game 1 starter in every World Series from 1955-1958, becoming the first pitcher in history to start four consecutive Game 1s. Ford repeated the feat again from 1961-1964.

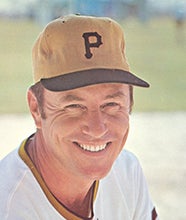

Ford’s scoreless streak in the World Series began in the 1960 Fall Classic against the Pittsburgh Pirates. Straying from his usual strategy, manager Casey Stengel started Ford in Games 3 and 6 of the series. Ford was dominant in his starts, throwing two shutouts, but he was unavailable to pitch in Game 7 – which ended with a 10-9 Pittsburgh win when Pirates second baseman Bill Mazeroski closed the series with a walk-off home run.

In 1961, Ford produced perhaps his best season in a major league uniform. The Yankees ace compiled a 25-4 record with a 3.21 ERA while leading the league with 283 innings pitched en route to his first and only Cy Young Award.

In a year when teammates Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle dominated the headlines while chasing Babe Ruth’s single-season home run record, Ford took his own run at the Babe. Back on the hill for Game 1 of the 1961 World Series, Ford baffled the Cincinnati Reds and allowed only two hits during his third consecutive Fall Classic shutout.

The stage was set in Game 4 on Oct. 8 at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field. The Reds looked to tie the series at two games apiece, but Ford had other plans. Needing to throw three innings of scoreless baseball to break Ruth’s record, Ford proceeded to throw five shutout innings and lead the Yankees to a 7-0 victory.

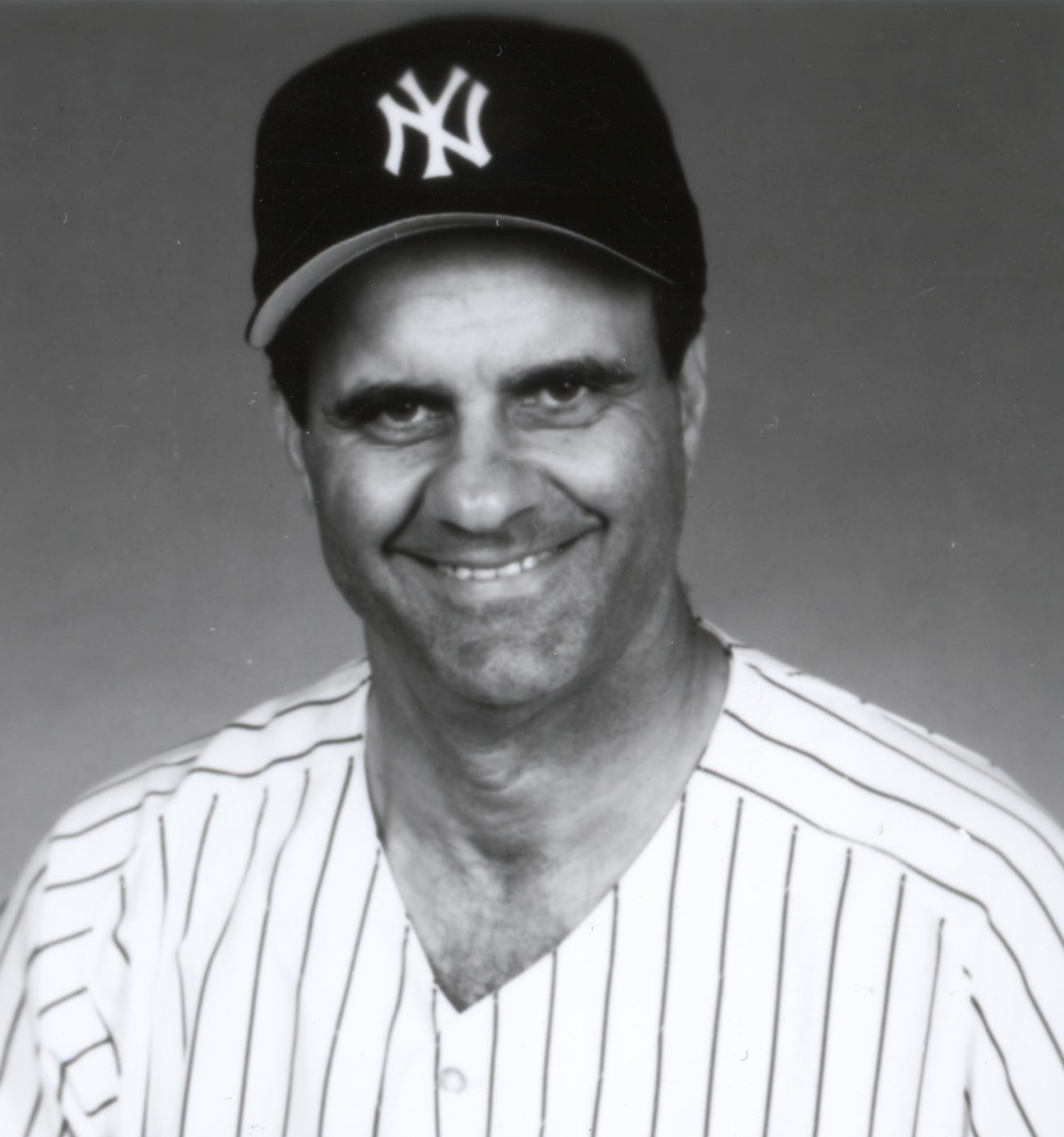

“He was the greatest pitcher I ever saw,” said manager Ralph Houk, who watched Ford from the Yankees bench from 1961-63. “He had a pitch for every situation and every hitter.”

Ford retired an additional five batters to begin Game 1 of the 1962 World Series to cap his scoreless streak at 33 2/3 innings. Ford’s overall winning percentage of .690 stands as the best in baseball’s Modern Era.

“He was an artist,” said Hall of Famer Joe Torre. “He wasn’t overpowering, but he was still intimidating.”

Matt Kelly was the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum