- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Shriners at baseball’s shrine

#Shortstops: Shriners at baseball’s shrine

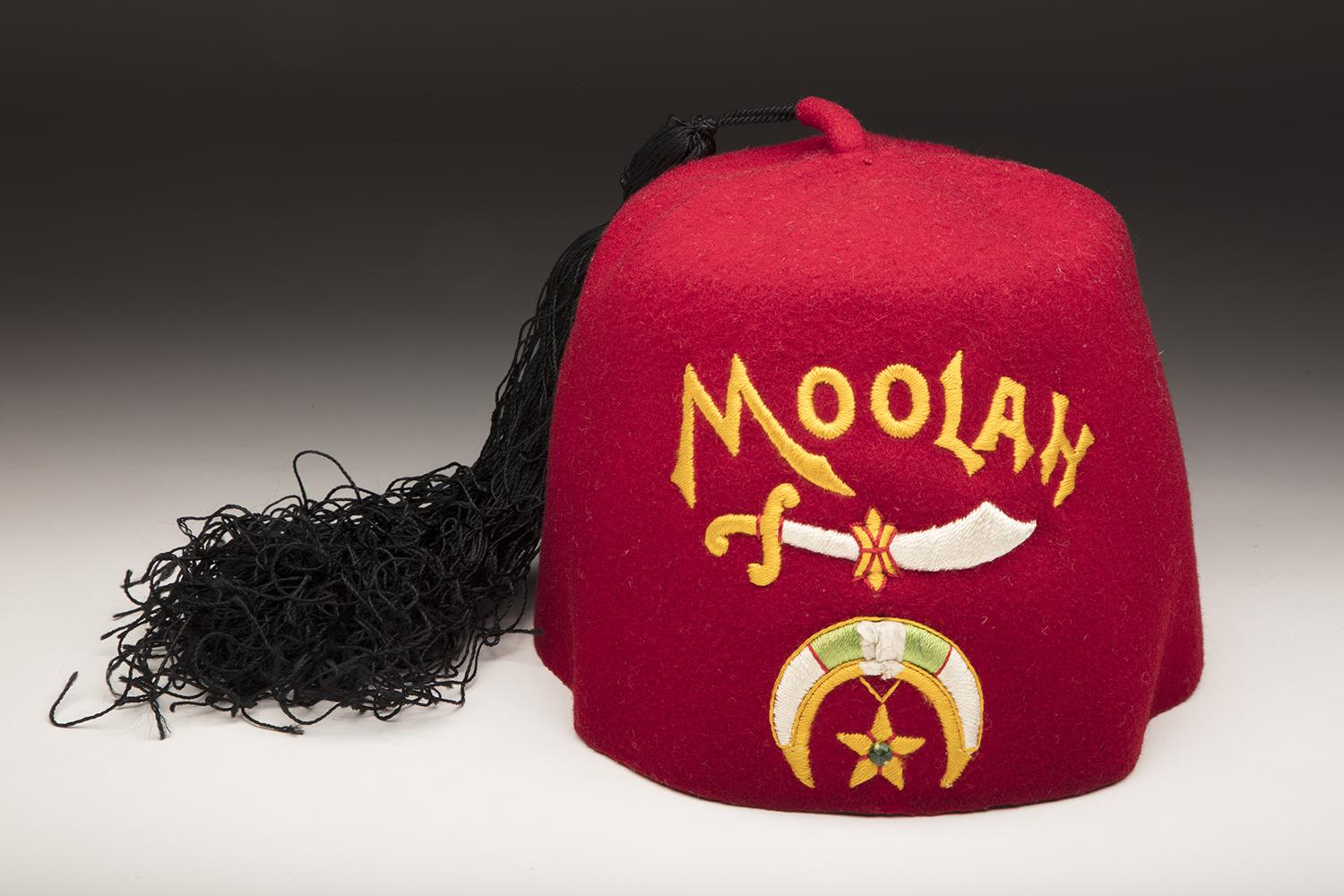

It is small, made of dark red felt, has a tassel, and the word Moolah is embroidered in yellow thread. This fez does not look like it belongs in the collection of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

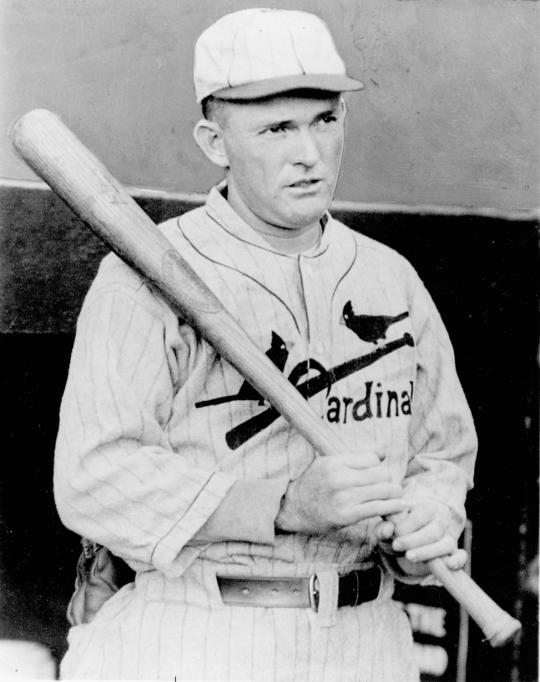

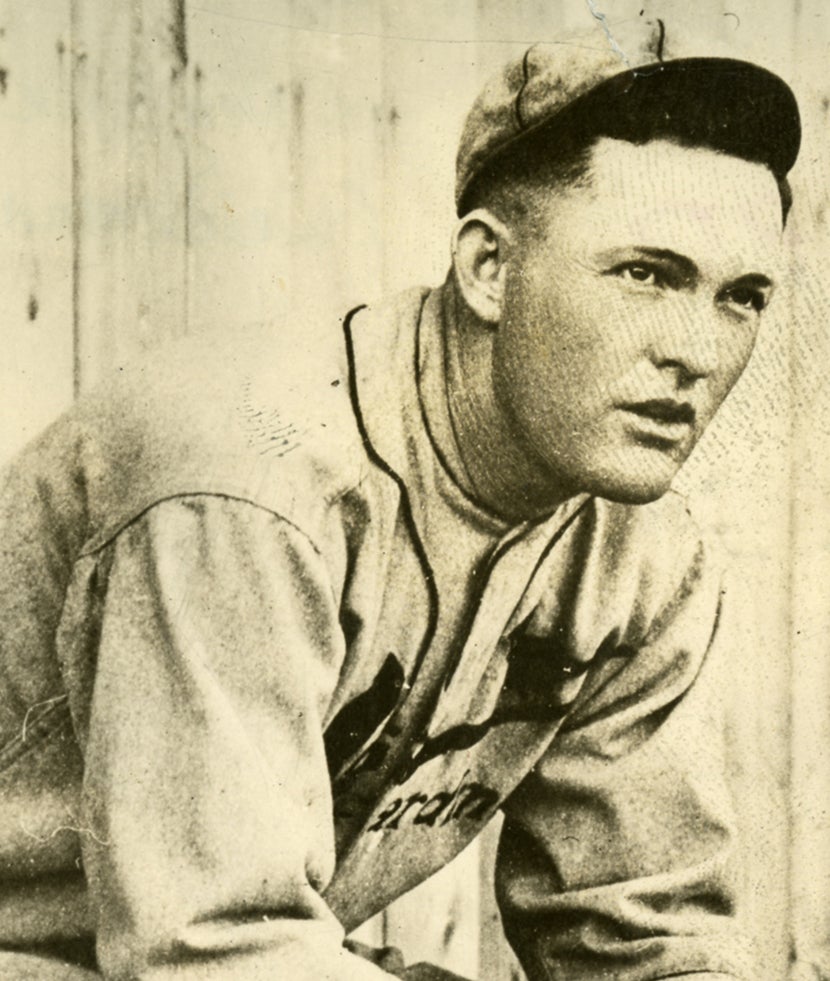

However, upon further inspection one would learn that the fez previously belonged to a Hall of Fame member appropriately nicknamed “The Rajah” – Rogers Hornsby.

Hornsby was famously quoted as saying, “People ask me what I do in winter when there's no baseball. I'll tell you what I do. I stare out the window and wait for spring.” However, Hornsby apparently also spent his winters in meetings of the fraternal organization the Freemasons.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

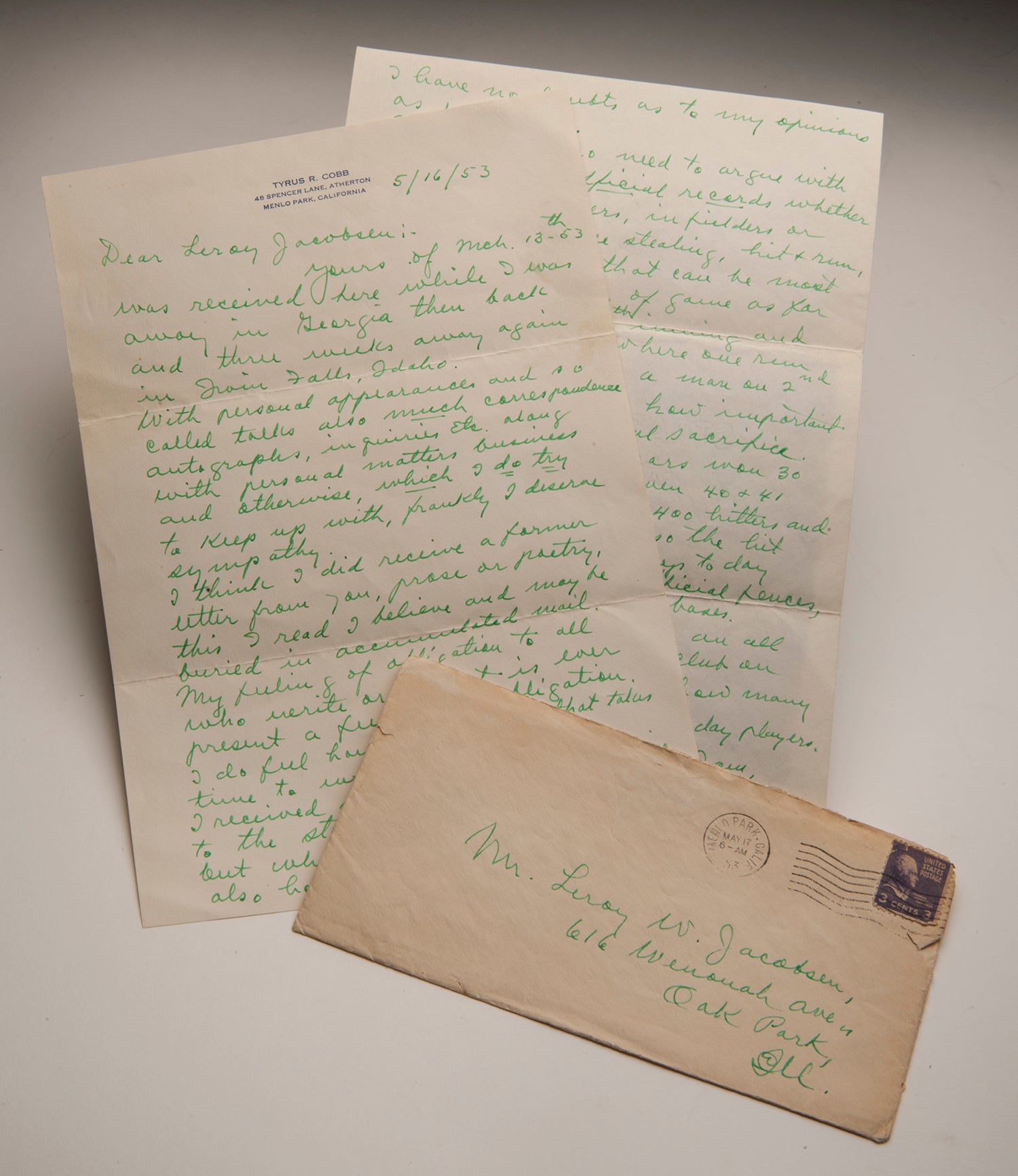

Hornsby joined the Freemasons during the spring and summer of 1918 and later joined the Masonic organization The Ancient Arabic Order of Noble Shrines (commonly known as Shriners) at an unknown date, but transferred membership to the Moolah Shrine in St. Louis on Nov. 7, 1952.

Most Americans may think of Shriners as being the men in fezzes driving funny little cars during parades, however there is much more to the organization. The Shriners had their first initiation on Aug. 13, 1870 at the Masonic Hall in New York City. The society was created to celebrate fun and fellowship, but in 1920 the Imperial Council voted to form a committee to find a location for a “Shriners Hospital for Crippled Children”. This group later decided it was better to establish a network of Shriners Hospitals for Children across North America. Today these 22 hospitals, which focus on children’s orthopedic care, burn treatment, cleft lip and palate, and spinal cord injury rehabilitation, do not charge patients for their care.

Hornsby joining the Freemasons should not come as a surprise, as at least 58 others enshrined in Cooperstown also joined the organization. There are many theories as to why so many of baseball’s greats have joined this particular institution. However, one particular quote from Hornsby may help shed light onto why the Freemasons were so important to him. In his autobiography My War with Baseball, Hornsby quotes his words in a disagreement with St. Louis Browns owner Donald Barnes. Barnes had refused to let Hornsby repay a debt with money won at the horse track as Barnes thought gambling to be immoral. Hornsby replied with, “That money is as good as the money you take from people in the loan-shark business. It’s better than taking interest from widows and orphans.”

Freemasons are a fraternal organization that look to help others, especially widows and orphans. While not an orphan himself, Hornsby did lose his father at the age of two. This caused him and his five older siblings and their widow mother to move and take jobs in the meat packing industry. Hornsby started working part-time at a meat packing plant at the age of 10.

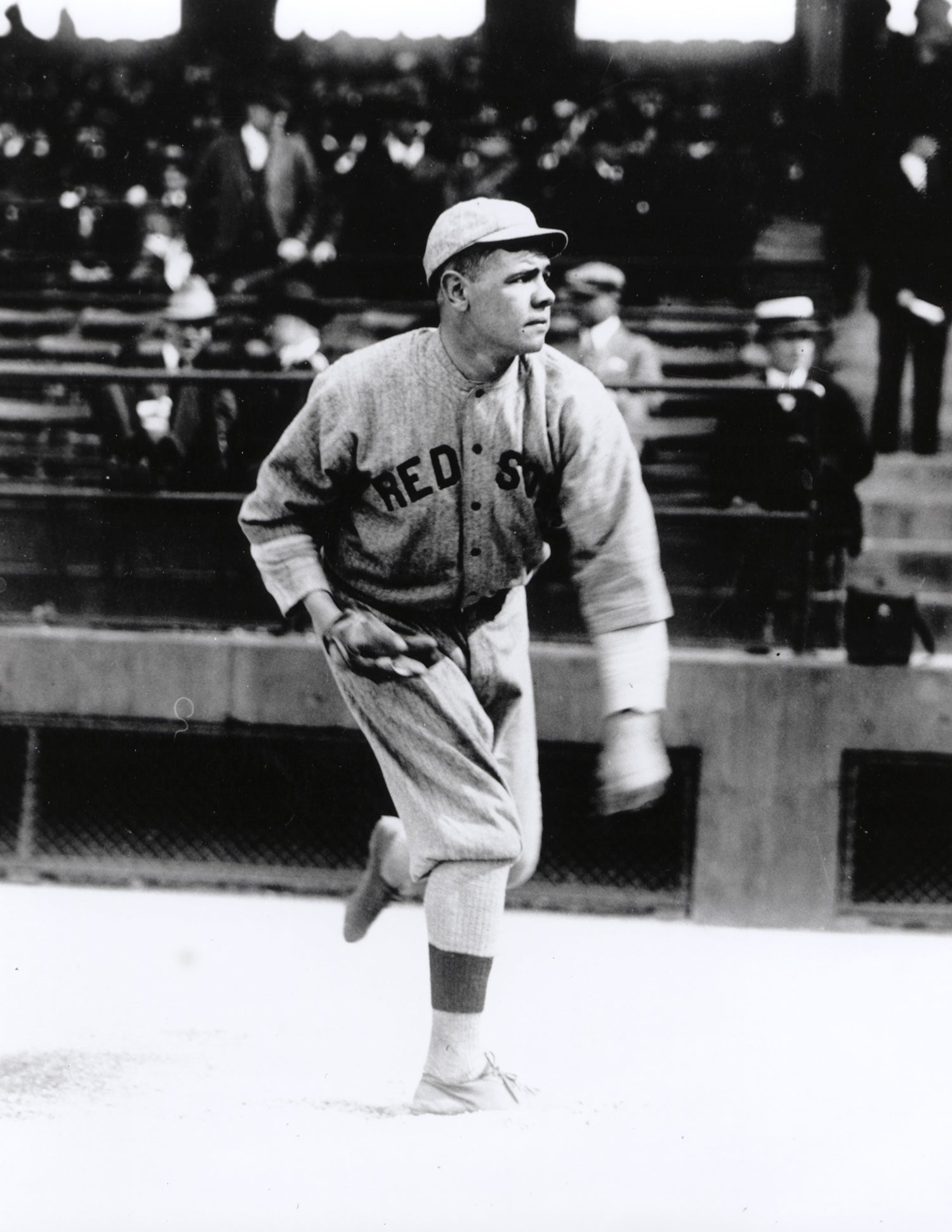

Interestingly, the Rajah – who has the highest career batting average for a right handed hitter (.358) – is not the only Hall of Fame member to have a Shrine fez in the Hall of Fame collection. Another fez is also in the collection, the one belonging to the man with the highest career batting average in major league history (.366), Ty Cobb. Cobb’s fez looks very similar to Hornsby’s with the exception that his has the work Moselm across it rather than Moolah – this slight difference shows that Cobb joined the Moslem Shrine in Detroit while Hornsby joined the Moolah Shrine in St. Louis.

Nathan Tweedie was the manager of on-site learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum