- Home

- Our Stories

- The Talent and the Temper of Oliver Marcelle

The Talent and the Temper of Oliver Marcelle

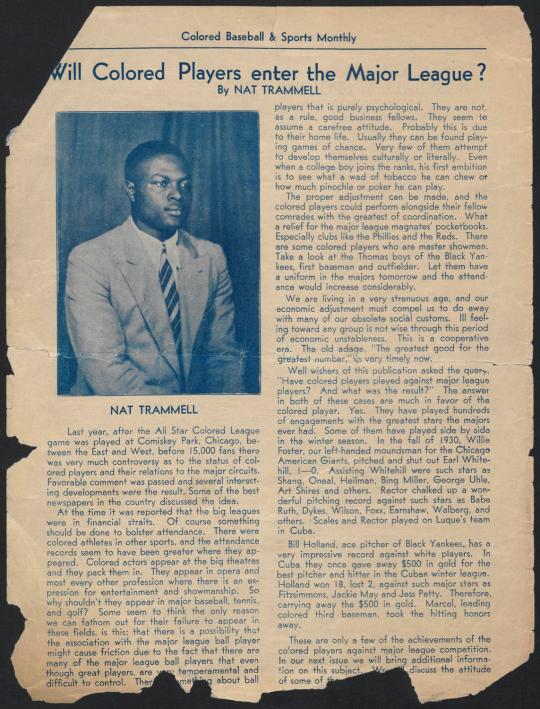

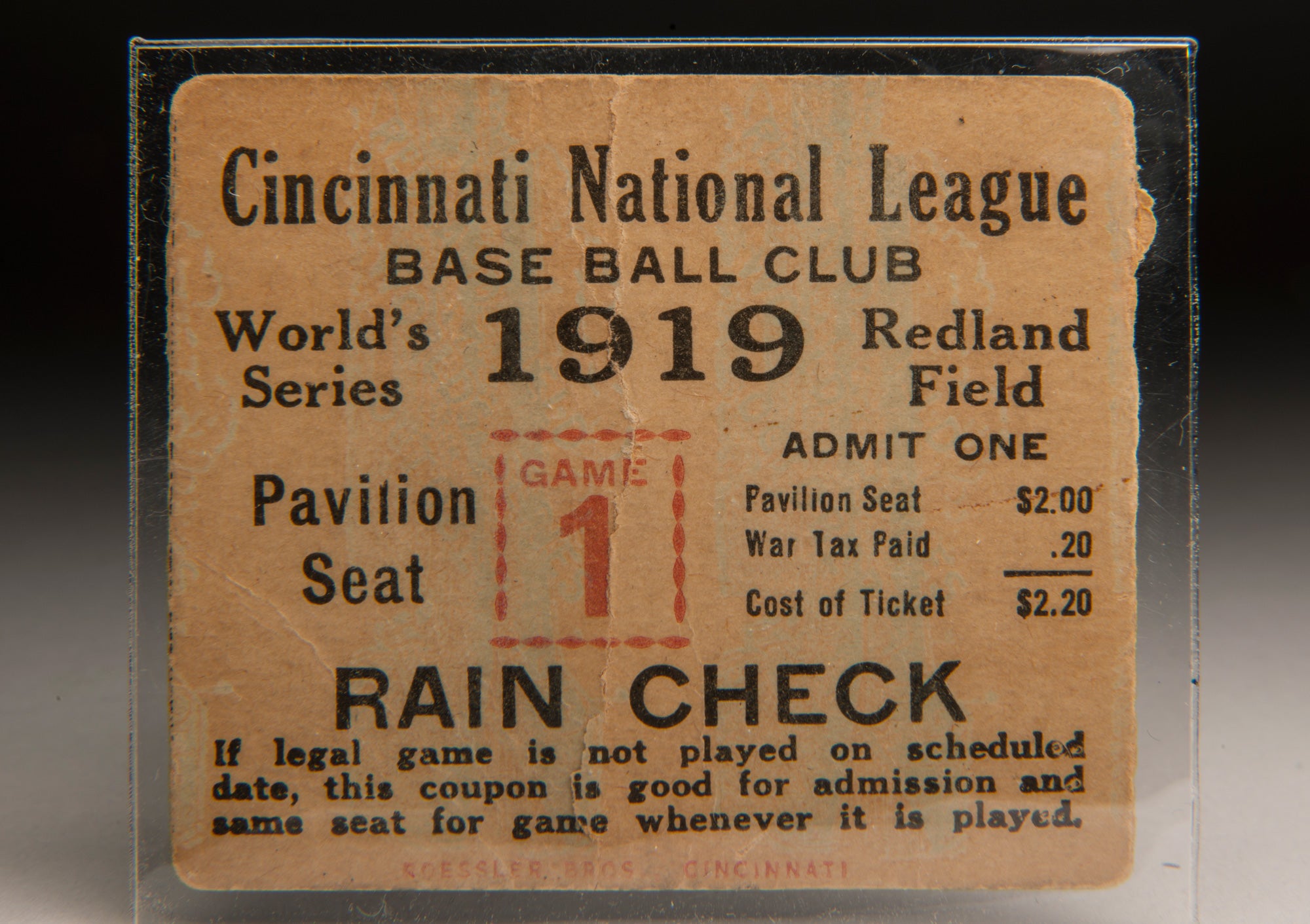

Long before Jackie Robinson integrated the Major Leagues in 1947, sportswriters in African-American newspapers had been advocating for the big leagues to allow Black athletes onto the field. One example appears in the Sept. 1, 1934 Colored Baseball & Sports Monthly, written by editor Nat Trammell, a document recently digitized by the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum and now available in the Museum's online collection, PASTIME.

In “Will Colored Players enter the Major Leagues?”, Trammell points out that Black players and white players have already played with and against each other, and he references a number of exhibition games, specific players, and the Cuban winter leagues. It was in Cuba, he recounts, where Bill Holland, an ace pitcher for the Black Yankees, facing Black, white, and Latino players, won $500 in gold for being the best pitcher in the league (over $6,800 in 2016 dollars). Then, almost as an afterthought, Trammell adds, “Marcel, leading colored third baseman, took the hitting honors away.”

Trammell may have given brief notice to Oliver Marcelle (sometimes spelled “Marcell,” “Marcel” or “Marsel”) because he was probably not who Trammell wanted to see integrate the Major Leagues; he was known as a terrific player, but equally for having a terrific temper.

Nat Trammell's "Will Colored Players enter the Major League?" appeared in the Sept. 1, 1934 "Colored Baseball & Sports Monthly." In it, he mentions, almost in passing, that Marcelle had won $500 in gold in the winter Cuban League. BA-EPH-Negro-Leagues-7-002. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Explore PASTIME

But Marcelle, a Creole from Louisiana, is no footnote in Negro League history. And that season in Cuba, when Holland and Marcelle each carried home $500 worth of gold, they were teammates on a historic team. Even today, Cubans speak of the 1924 Leopardos de Santa Clara like many baseball fans speak of the 1927 Yankees. It was simply the greatest team the country had ever known.

Besides Marcelle and Holland, Santa Clara had Oscar Charleston and Cuban pitcher José Méndez, both later elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. And while the other three teams in the league were comprised of big league players and future Hall of Famers like Martín Dihigo and John Henry “Pop” Lloyd, they offered little competition to the Leopardos.

So dominant were the Leopardos – frequently scoring in the double-digits – that they took an insurmountable lead in the standings. With the championship a foregone conclusion, attendance dropped. The league responded by simply cutting the season short and declaring Santa Clara the champions. They finished with a 36-11 record (.766 winning percentage), 11.5 games in front of the next best team. The league then broke up the last-place team and reassigned its best players to the other two teams competing against Santa Clara, for a shortened second season, which Santa Clara won as well (though only by half a game). Santa Clara led the league in virtually every offensive category, including runs, doubles, home runs, hits, and stolen bases. The team hit a collective .331, a Cuban League record, with Marcelle leading the way at .393.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

In addition winter ball, Marcelle played stateside, beginning in 1918. He played for a number of teams, winning pennants twice with the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants and once with the Baltimore Black Sox.

Marcelle regularly hit above .300 and played stellar defense. Baseball Hall of Famer Judy Johnson, normally a third baseman, said that when he played with Marcelle in Cuba, Johnson was moved to second base so Marcelle could stay at third. According to another Negro League third baseman, Bobby Robinson, Marcelle played 10 feet closer to the plate than any other third baseman dared. He was quick enough to knock down line drives to either side, and he essentially eliminated the possibility of opponents bunting to the left side of the infield.

Pop Lloyd called him the greatest third baseman in the Negro Leagues, and a 1952 poll in the Pittsburgh Courier came to the same conclusion. But in spite his enormous talent, Marcelle was a difficult teammate.

Buck O’Neil said people called him “The Ghost” because he would disappear after the game, not to be seen in his hotel room, and then reappear the next day at the ballpark. His nights were spent on the town. At a bar in 1925, he was involved in an altercation that ended with a man being shot and killed. Marcelle was arrested, but not charged after it was determined Marcelle hadn’t fired the gun.

He lost his temper on the field, too, arguing with umpires, fighting with opponents, and clashing with teammates. Once in a game, in a rage, he hit teammate Oscar Charleston over the head with a baseball bat.

His temper was well-known by fans, who would taunt and heckle until it affected his play. Wrote one columnist in a 1924 article in the New York Age, “He was a victim of almost uncontrollable temper, as he let fans and umpires get his goat.”

In 1930, a game of cards with teammate Frank Warfield dissolved into a brawl. Warfield ended up in jail, and Marcelle ended up in the hospital, with a large chunk of his nose bitten off. Marcelle would play future games with a patch on his nose. Some said his vanity and the ridicule from opposing players and fans led him to retire, but the fact is that that Marcelle, then 33, was in decline. He continued to play, but for independent and second tier teams, and he barnstormed as late as 1934. That year, he retired, moved to Denver, and took odd jobs to support himself, mostly painting houses.

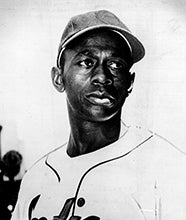

Denver at the time held the Denver Post Tournament, biggest semi-pro and independent team tournament in the United States, dubbed “The Little World Series.” According to Chet Brewer, a star pitcher for the Kansas City Monarchs, Marcelle urged the organizers at the Post to include independent Negro League teams. Two teams broke the color line at the 1934 tournament: the Monarchs (then independent) and the integrated House of David barnstorming team, which at the time was borrowing Satchel Paige from the Monarchs (the two clubs often cooperated on tours). The Monarchs proved no match for the white teams assembled, and Paige almost single-handedly powered his club to the championship. More significantly, the tournament introduced Paige to a nation-wide, white audience, an important step in the road to integration.

This was the same year that Marcelle was mentioned as an afterthought in the editorial by Nat Trammell. Both Trammell and Marcelle, it turns out, were fighting equally for the same cause.

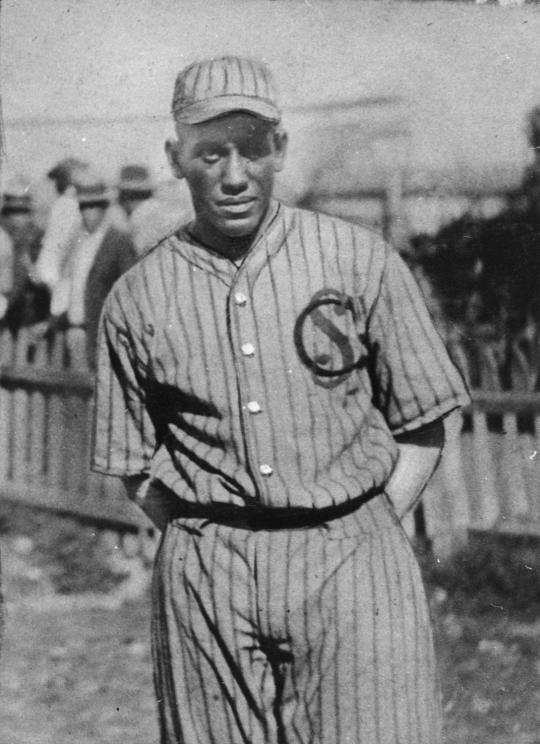

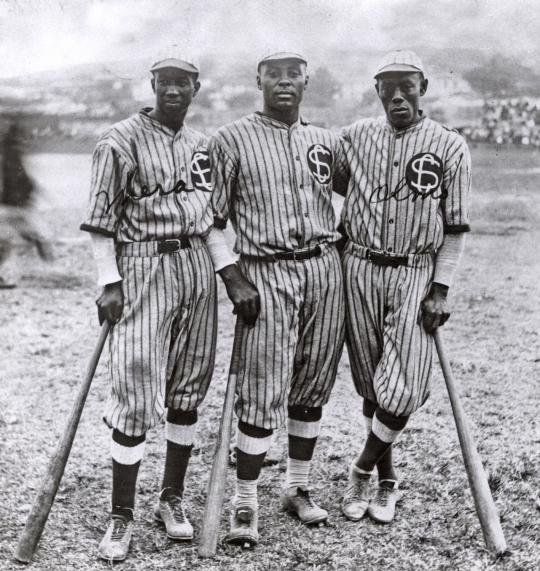

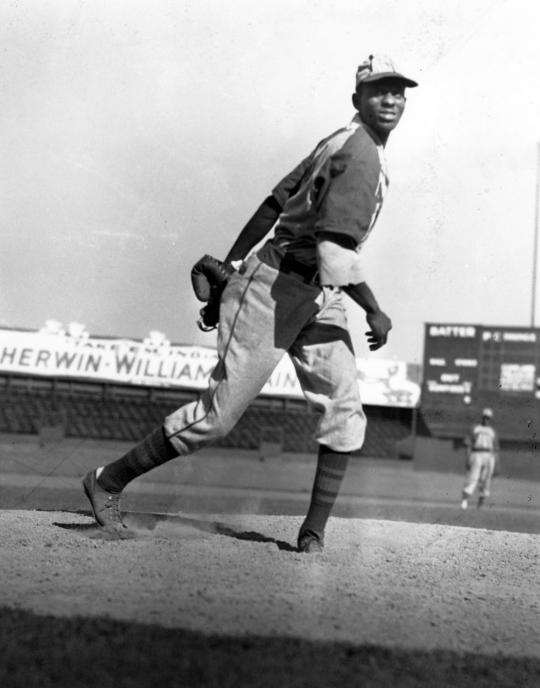

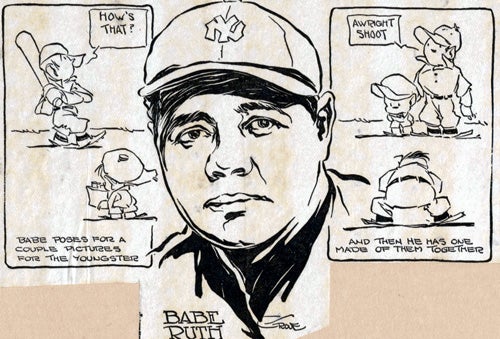

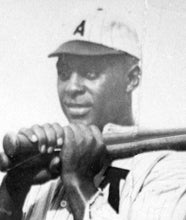

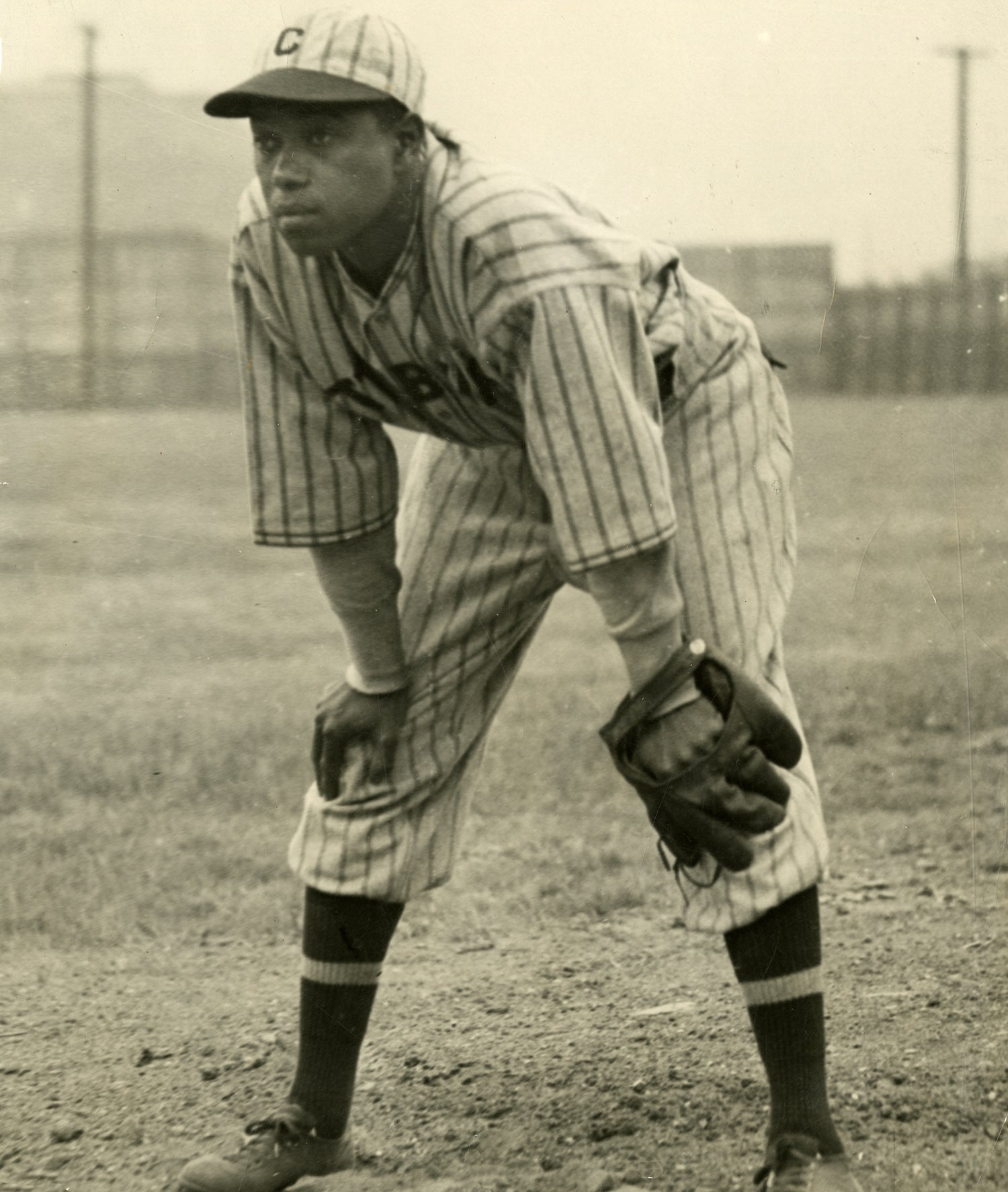

Hall of Fame Outfielder Oscar Charleston, center, was a frequent teammate of Marcelle's. Here he stands with fellow outfielders Pablo Mesa, left, and Alejandro Oms, right, who comprised the outfield for the legendary 1923-24 Leopardos de Santa Clara. Charleston-Oscar-6550.76_Grp_PD (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

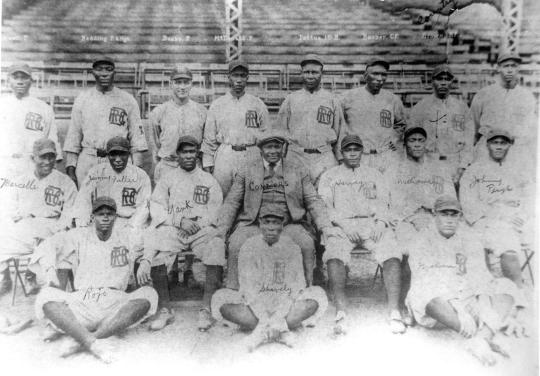

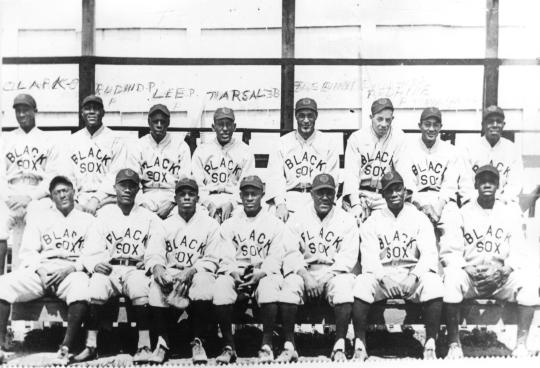

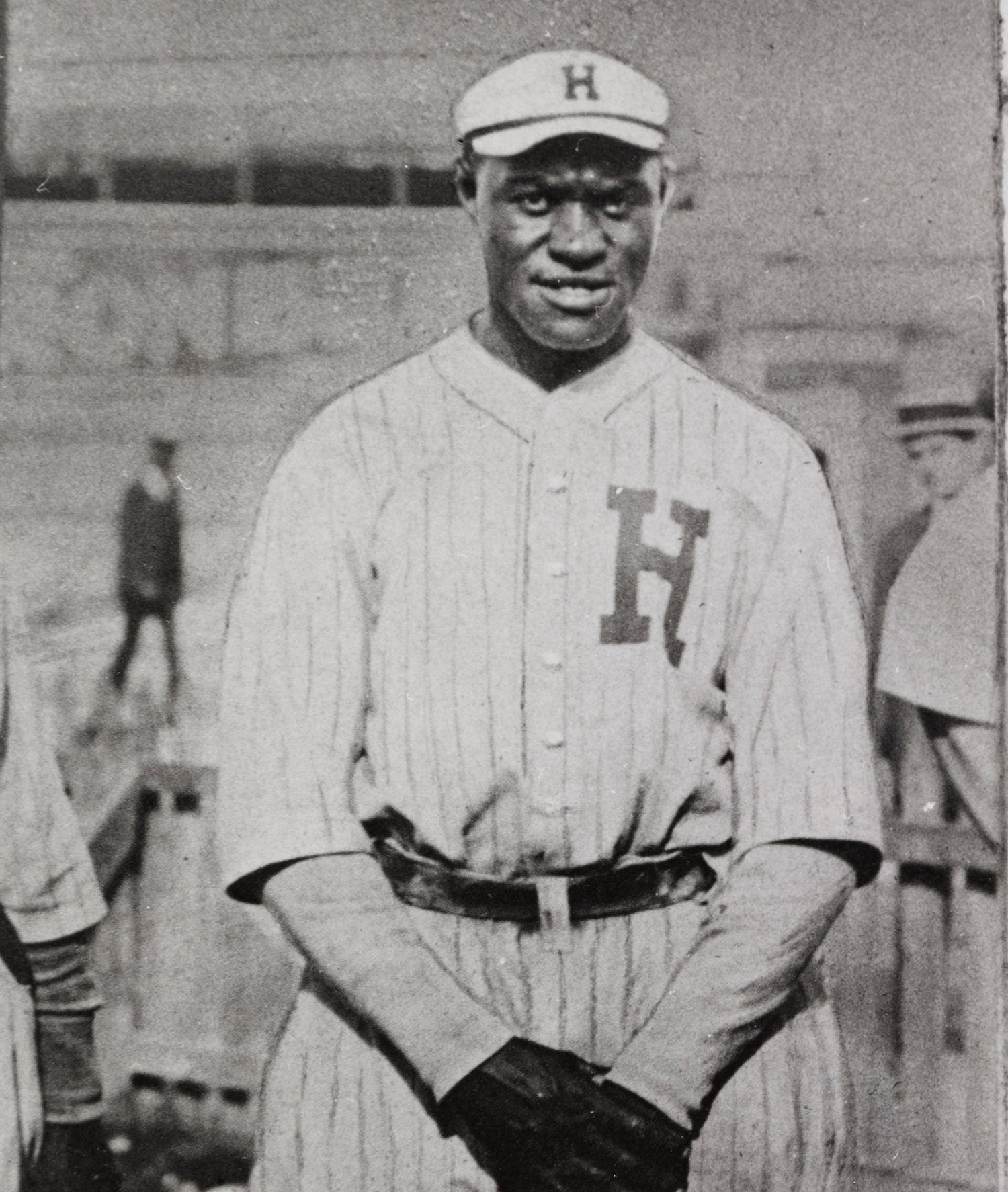

The 1929 American Negro League champion Baltimore Black Sox, featuring the "Million Dollar Infield," so named for the prospective worth of the players had they been white. Marcelle is in the back row, fourth from the left. Frank Warfield, who bit off part of Marcelle's nose in a bloody fight, is in the front row, middle. Baltimore_Black_Sox_1929.2226.73_PD (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Marcelle would continue to recruit Black players to the Denver Post Tournament, and continue to paint houses. He died in 1949, just before his 54th birthday, of arteriosclerosis, in poverty, and was buried in an unmarked grave. His story, and countless others, live on in the Hall of Fame Digital Archive, which recently released its newest selection of digitized materials to the public : photos and documents pertaining to Negro League history. Dive into their legacies, at collection.baseballhall.org.

Explore PASTIME

Larry Brunt is the Museum’s digital strategy intern in the Class of 2016 Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Youth Leadership Development. To support the Hall of Fame Digital Archive Project, please visit www.baseballhall.org/DAP