- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: The ‘Happy’ Exile

#Shortstops: The ‘Happy’ Exile

Every city has its local baseball hero. For Milwaukee, it is Oscar Emil Felsch.

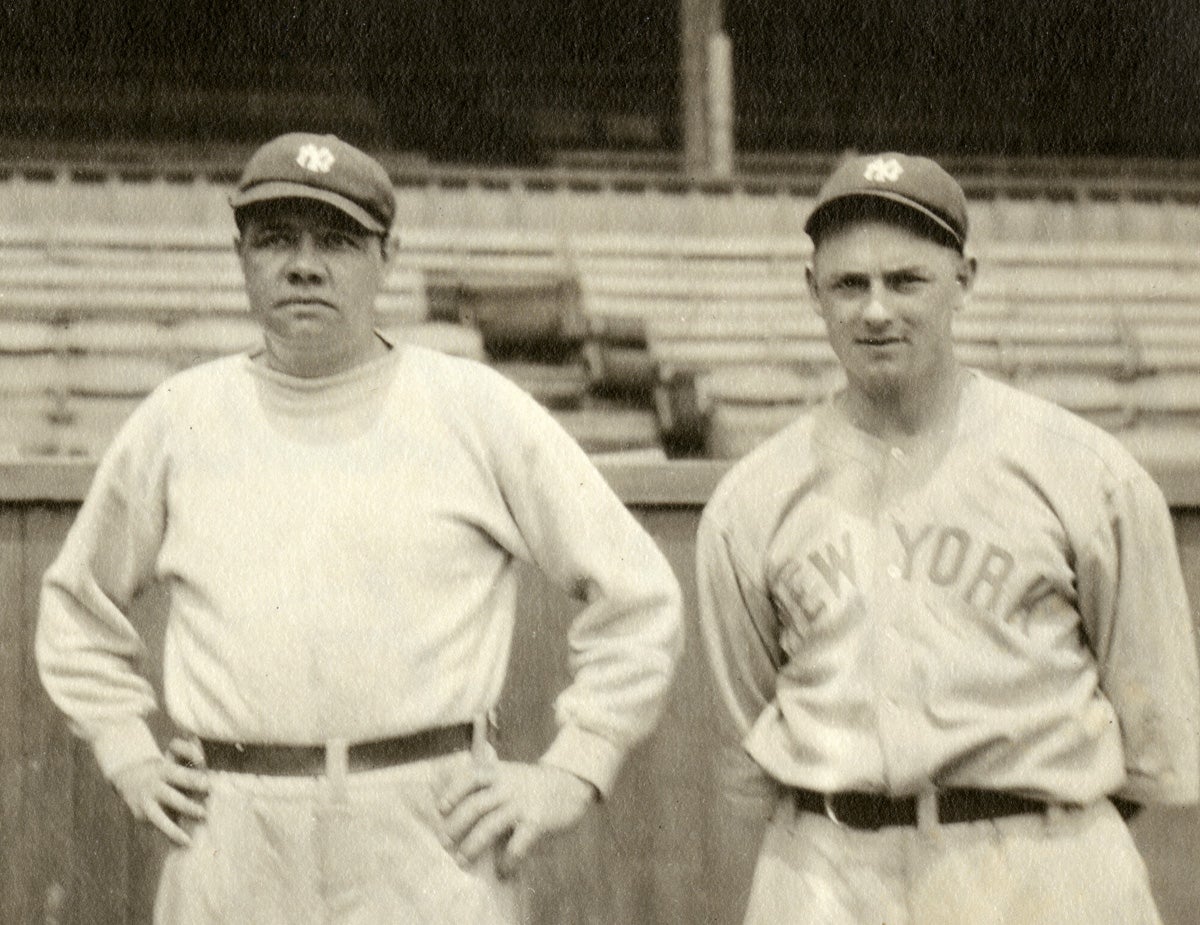

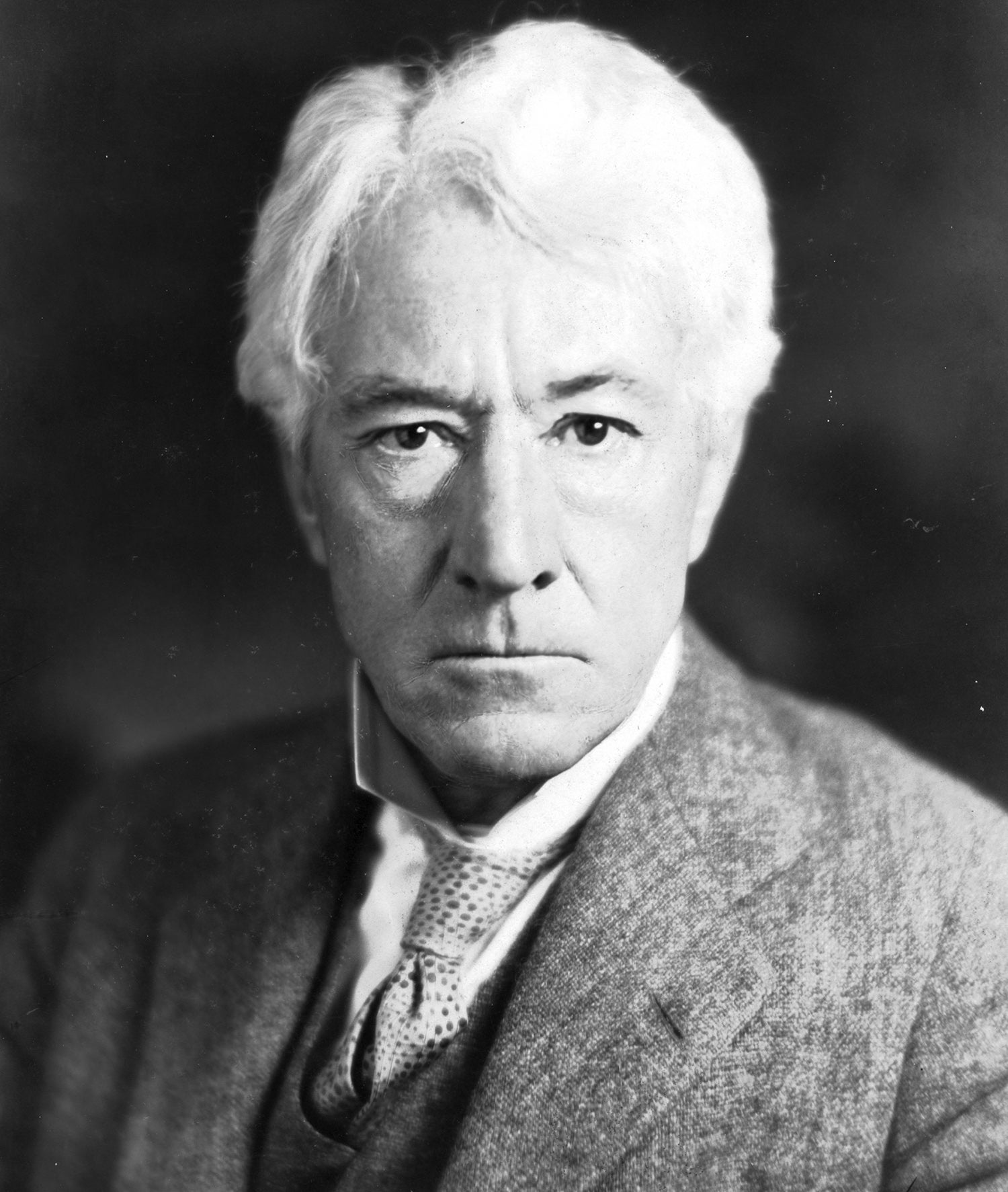

Because of his exuberance, he was bestowed the nickname “Happy”, although ironically, his face rarely exudes happiness in surviving photographs. He began his “Dead Ball” era career starting in the local sandlot leagues of Milwaukee’s North Side and rising to play for the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association. Known for his speed and power, Felsch’s contract was purchased in 1914 for $12,000 by owner of the Chicago White Sox, Charles Comiskey – a man not known for spending lavish sums on players. But Felsch was that good.

For six seasons, Felsch developed into one of the most dominant players of his era. In the 1919 season, Felsch set a major league record with 14 outfield double plays, which continues to be the top mark in history. His best season batting was during the 1920 campaign when he hit .338 with 115 RBIs and an eye-popping 14 home runs.

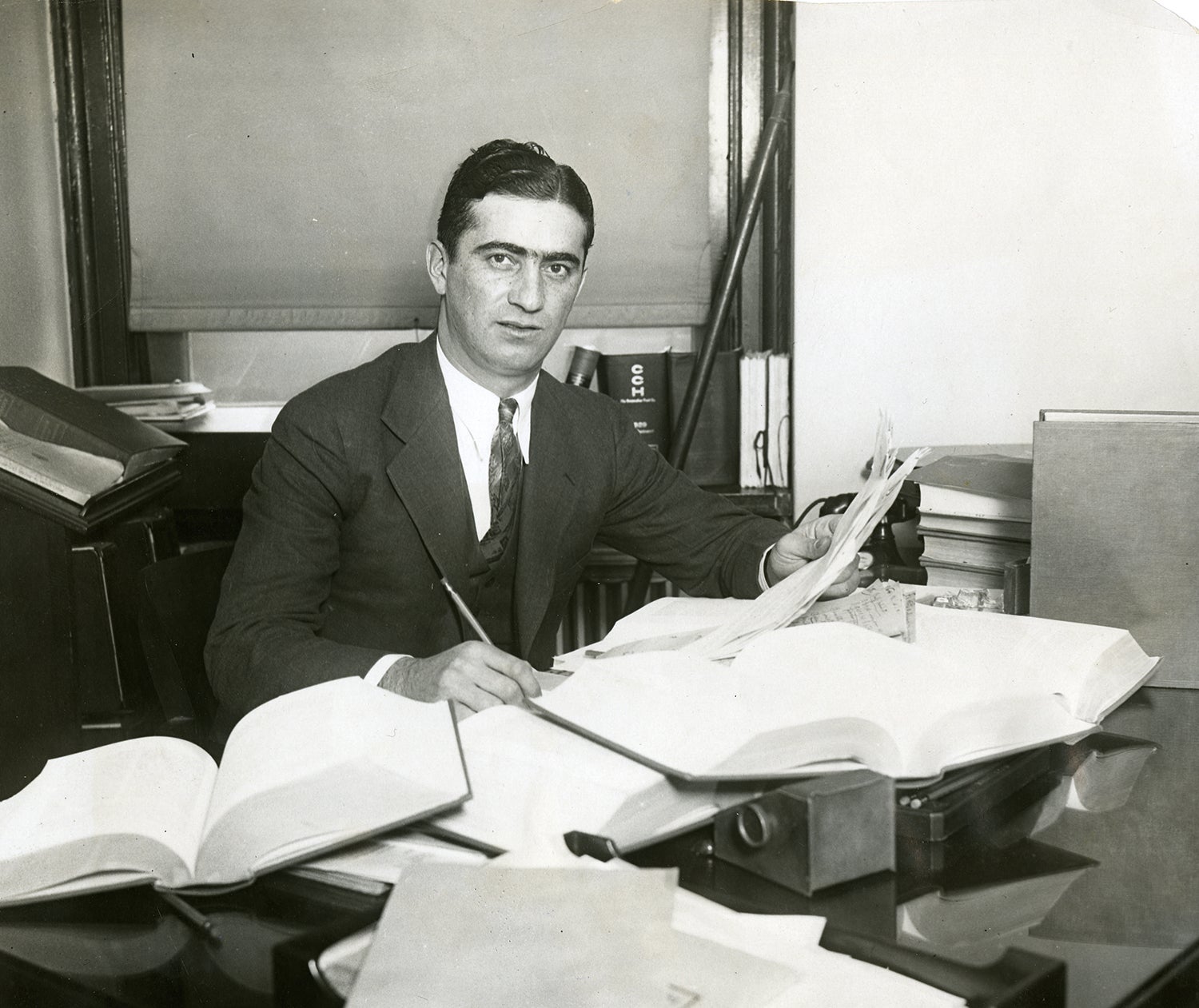

Despite his status as a top player, Felsch’s major league career was tarnished by rumors that he accepted bribes from gamblers to purposefully lose the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds. After two years of accusations and trial, the legal system absolved Felsch and his teammates from any wrongdoing. However, the newly elected Commissioner of Major League Baseball, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, disagreed and banned the “Black Sox” from participating in professional baseball in perpetuity. But Happy continued to play baseball as an exile.

In 1922, he first joined a team of “Ex-Major Leaguers” including former Black Sox teammates and other banned players to play in small towns. After founding a grocery store in Milwaukee, he continued to play for the Twin City Red Sox in central Wisconsin, which pitted him against African Americans and Native Americans.

In 1925, Felsch accepted a contract from a semi-pro team in Scobey, Mont., for the generous sum of $600 a month plus expenses to play baseball in the upper-Midwest and Canada. The citizens of Scobey turned a blind eye to Felsch’s past transgressions and lauded his still impressive feats on the baseball field, but the same cannot be said for opposing fans, who taunted Felsch.

In one case, Felsch was playing a game in Canada when an irate spectator spewed verbal barbs in Felsch’s direction, making fun of his exiled status in baseball. Later that evening the same spectator drunkenly approached Felsch and a teammate, and a physical confrontation ensued. For nearly three years, Felsch dominated the local teams, but that soon came to an end when the financial backers of the Scobey team curtailed their support.

Felsch continued to play semi-pro ball for various clubs and barnstormed in Montana and Canada through 1930. He returned to Milwaukee and played with sandlot teams despite his ever increasing age and weight which caused the “jolly” player to move from outfield to first base. Felsch continued opening local fountains and taverns (once Prohibition ended) and played sandlot baseball in the Milwaukee area. After several years, he left the saloon business and continued working as a crane operator at George Meyer Company from 1949 to 1962.

During his final years, he was interviewed by several sportswriters who recounted his playing days nearly 50 years earlier, one of which became the basis for Eight Men Out: The Black Sox and the 1919 World Series. With his playing days long behind him, Felsch continued to follow baseball by listening to Milwaukee Braves radio broadcasts until his death in 1964 at the age of 73. Although he remains primarily remembered and scrutinized for his association to the Black Sox scandal, his status as Milwaukee’s premier hero of the “Dead Ball” era will live on in the annals of baseball history.

Michael Fishbach was a 2017 digital strategy intern in the Hall of Fame’s Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Youth Leadership Development