- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Ticket to History

#Shortstops: Ticket to History

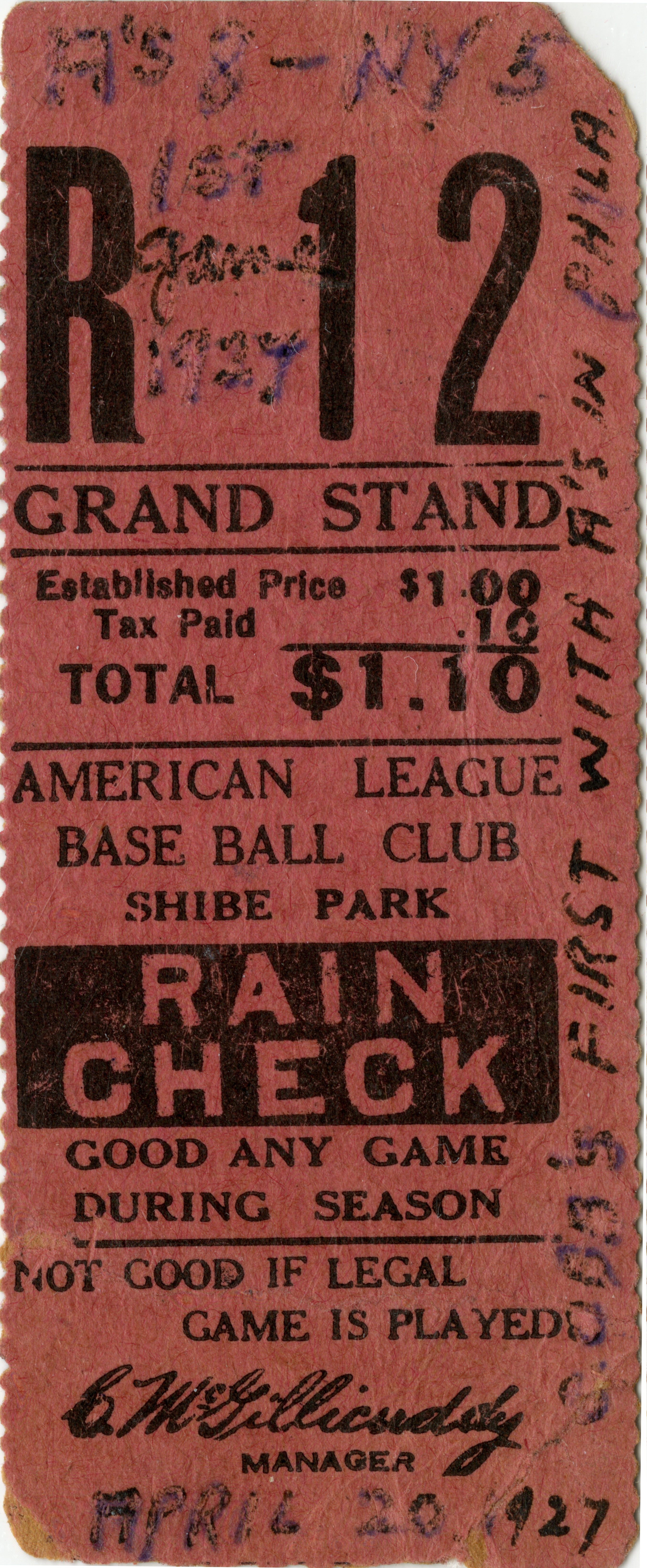

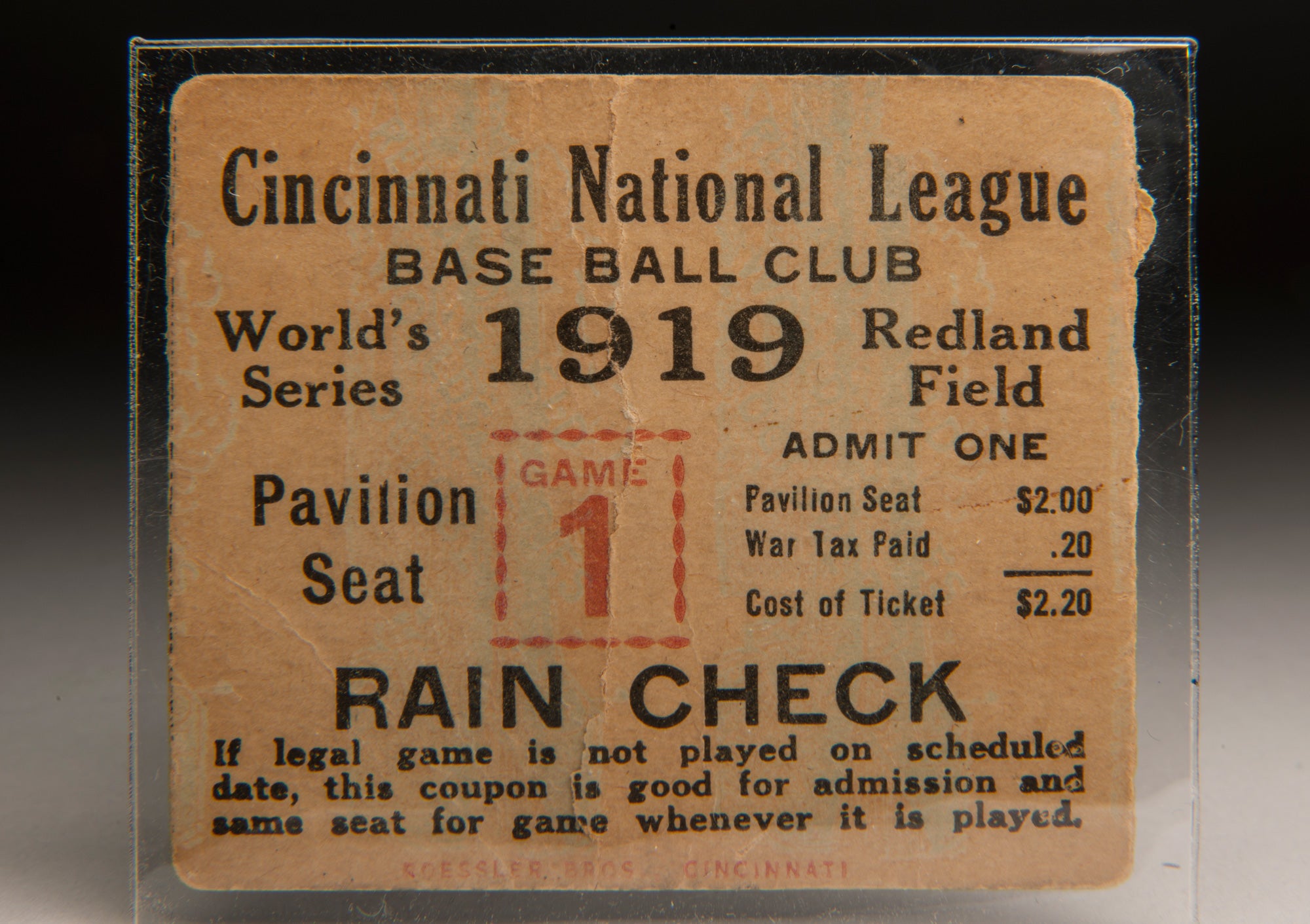

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum has a long, rich history – but sometimes not all of its history is found in Cooperstown. That is, not until it is donated.

Take, for example, the Hall of Fame Game. Begun in 1940 and scheduled through 2008, the annual contest typically – but not always – featured an American League team against a National League team. In the days before air travel, the teams were often those taking the New York Central Railroad between New York or Boston and the Midwest.

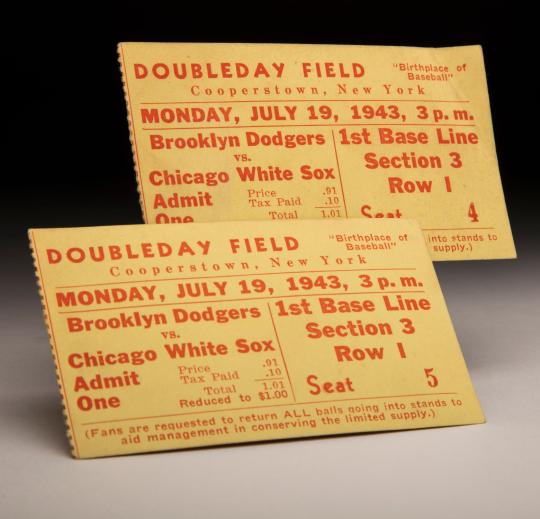

So it was on Monday, July 19, 1943, when the Brooklyn Dodgers – leaving Boston and heading for Cincinnati – faced the Chicago White Sox, themselves destined for Boston after completing a long homestand.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The bearer of these one-dollar tickets for the 3 p.m. tilt got prime spots in the first base bleachers to witness the clash between these clubs, both in the first division of their respective leagues. Those tickets were recently donated to the Museum, filling a gap in its collection of tickets from the Hall of Fame Game.

The United Press, in a brief article in the July 19 issue of The New York Times, noted that the “exhibition, sponsored annually to honor Abner Doubleday, founder of the national pastime and to defray the expenses of baseball’s ‘hall of fame’ here, will be played in a wartime setting with much of the color of former years missing.”

Four years removed from the Baseball Centennial, many still believed Doubleday was primarily responsible for the invention of baseball. Though considered by some to be a dubious notion from the start, and thoroughly disproven since, in 1943, it still seemed like a good reason to hold the game – not to mention having the game receipts help offset the growing museum’s growing expenses.

Held during World War II, it is unclear what is meant by “much of the color of former years missing,” although the UP article also mentions the transportation restrictions in place in the United States. Such restrictions may have curtailed attendance at Doubleday Field – reports claim anywhere from 4,000 to 5,000 spectators – but the Binghamton Press described those persons arriving “by carriage, buggy, and foot power.”

One of the main attractions was not as prompt. Jack Smith of the New York Daily News noted that the “White Sox were a half hour late for the game and it would have been better if they hadn’t showed up at all.”

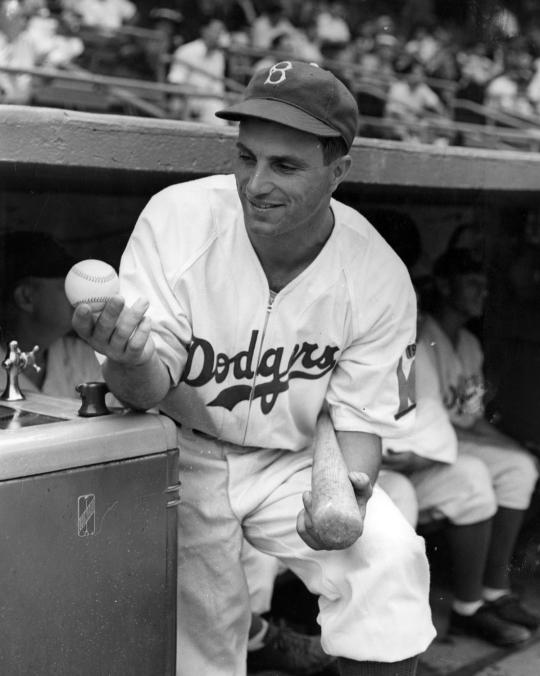

Chicago got off to a good start, however, pushing across five runs in the top of the first inning off the Dodgers’ starter, 41-year-old Freddy Fitzsimmons. Long removed from his peak days with the Giants, Fitzsimmons finished fifth in National League Most Valuable Player voting in 1940. White Sox first baseman Joe Kuhel hit a two-run home run following run-scoring extra-base hits by Luke Appling and Johnny Kolloway.

Fitzsimmons and reliever Rube Melton, who entered in the fourth inning, shut down Chicago after that, and with timely hitting and the help of four White Sox errors, Brooklyn rallied for a 7-5 victory.

Dolph Camilli, Mickey Owen, and Bobby Bragan led the Dodgers’ offense in their comeback win. Owen was a home run short of hitting for the cycle, and Camilli started the rally with a round tripper off White Sox starter Edgar Smith, who was fresh off a 10-day suspension.

Future Hall of Famer Paul Waner, in the latters years of his career, went hitless in five plate appearances for Brooklyn but made “three gaudy catches” in the outfield, according to the Times’ Roscoe McGowen.

McGowen also reported other pre-game tidbits, including Waner and four others playing nine holes of golf that morning. The left-handed Waner scored a group low of 47 with only two right-handed clubs at his disposal, a nine iron and a putter.

Camilli, Brooklyn outfielder Augie Galan, their manager, Leo Durocher, and their coach, Chuck Dressen, arrived at Doubleday Field at 10:30 a.m. to arbiter a youth baseball game. Durocher reported the final score as 25 to 15 and claimed they “saw two or three pretty good-looking players, too.”

There was also an unexpected equestrian demonstration about an hour and a half before the game, as Dixie Walker, Les Webber, and Johnny Barkley “appropriated three saddle horses … and raced around Doubleday Field. Asked where they found the steeds, Dixie said, ‘They were outside the park here and we just took ’em.’”

By the last scheduled Hall of Fame Game in 2008 (which was rained out), such antics would be unheard of – certainly there would be few, if any, horses available for the taking outside Doubleday Field.

Despite the donation of the 1943 tickets, there remain gaps in the Baseball Hall of Fame’s collection of Hall of Fame Game tickets – and tickets for its successor, the Hall of Fame Classic. We are seeking the public’s assistance in filling those holes in our collection.

According to registrar Peyton Tracy, the Baseball Hall of Fame is in search Hall of Fame Game tickets from 1942, 1944, 1950, 1951, 1960, 1974, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999 and 2003.

Tickets are also needed for Hall of Fame Classic games in 2011, 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, and 2018.

If you have tickets for any of these games and wish to donate them to the Museum, please let us know at info@baseballhall.org.

Matt Rothenberg is the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum