- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Video revolution

#Shortstops: Video revolution

From the Commissioner’s office down through the amateur ranks, baseball executives believe the future of the game involves embracing the latest technological advances.

But the evolution of today’s data analysis and video replay began over a century ago – in the earliest days of moving pictures. An example of that technology is now preserved at the Hall of Fame.

Les Mann, a major leaguer in the early 20th century, predicted it all: “The sport must be introduced by explaining the science, skills, and fundamental development both individually and collectively as a team.” He proved to be ahead of his times.

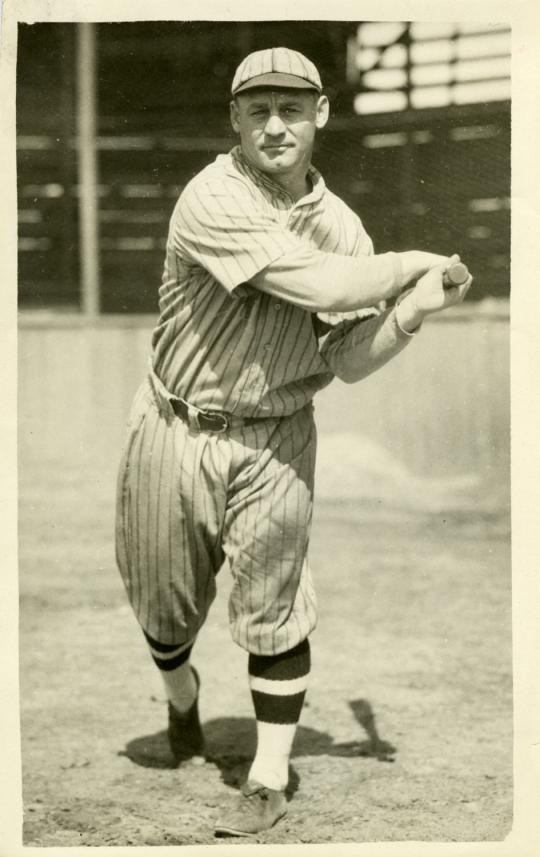

Born in 1892, Mann was a four-sport athlete in football, basketball, baseball, and track at Lincoln High School in Lincoln, Neb. After graduating, Mann moved east to attend Springfield College in Massachusetts, known then as the International Young Men’s Christian Association Training College. The right-handed outfielder also excelled at basketball and played varsity football as a freshman, but found his niche in baseball. Recruited by the Boston Braves, Mann debuted in 1913 and was a part of the 1914 World Series Champion “Miracle Braves,” who went from last to first place with two months remaining in the season. Mann ultimately played 16 seasons with the Boston Braves, Chicago Cubs, St. Louis Cardinals, and New York Giants.

Les Mann played 16 seasons in the big leagues and was a starting outfielder on the Miracle Braves team that won the 1914 World Series. But it was his contributions to the game after his playing days, including the invention of the Mannscope camera, which helped take baseball all over the globe. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Mann dedicated himself to building amateur sports and spent his offseasons doing so. He worked as the director of physical education and basketball coach at the Rice Institute (now Rice University) in Houston, Texas, the head baseball and basketball coach at Indiana University, and assistant football coach and head coach for baseball and basketball at Springfield College.

In 1924, he established the Leslie Mann Coaching System, based in Bloomington, Ind. He thought that if more people understood the appropriate basic skills of baseball, it would not only improve their health and physical fitness, but also shape their character. As a team sport, baseball was not about a single player, but about the honor and respect for the whole. In a letter to Mr. August “Garry” Herrmann, President of the Cincinnati Reds, Mann said, “I teach the game and believe in its honesty. Great elements of character are imbedded in one’s heart when he plays the game for the game’s sake and not the dollar.”

Mann believed that success in baseball was determined through not only skill, but also strength, passion, and determination.

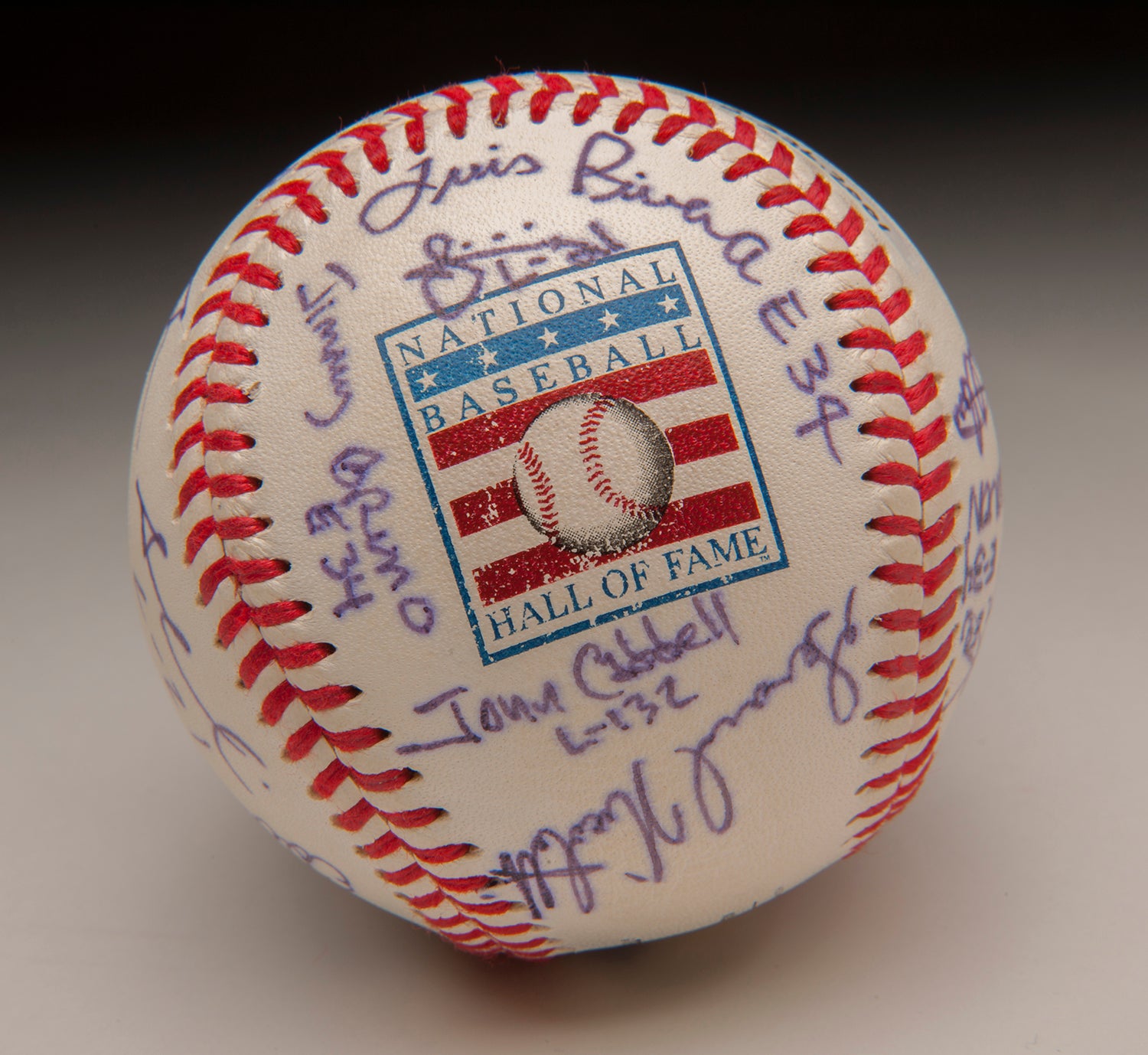

In 1924, Leslie Mann established the Leslie Mann Coaching System, based on the premise that if more people understood the appropriate basic skills of baseball, it would not only improve their health and physical fitness, but also shape their character. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

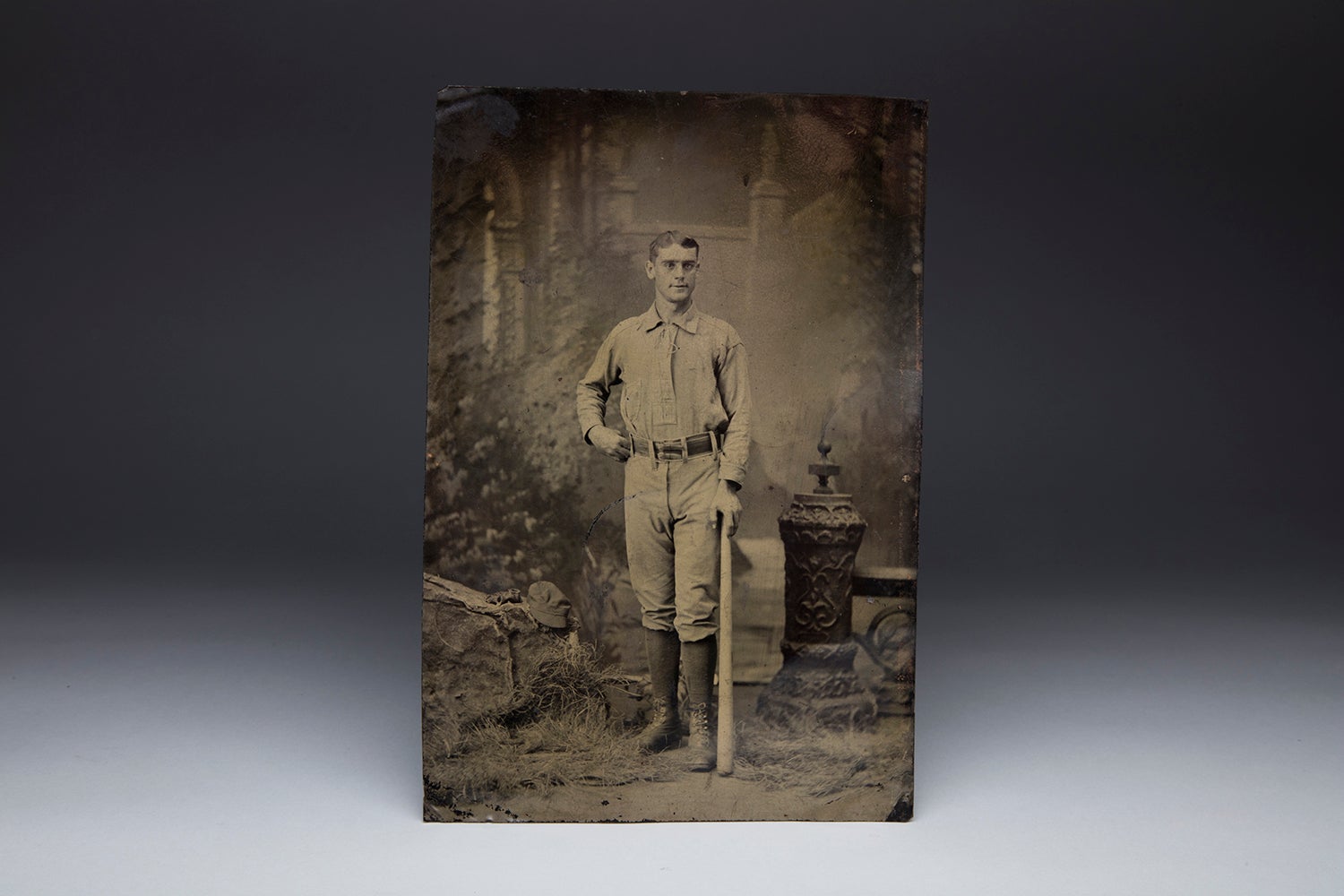

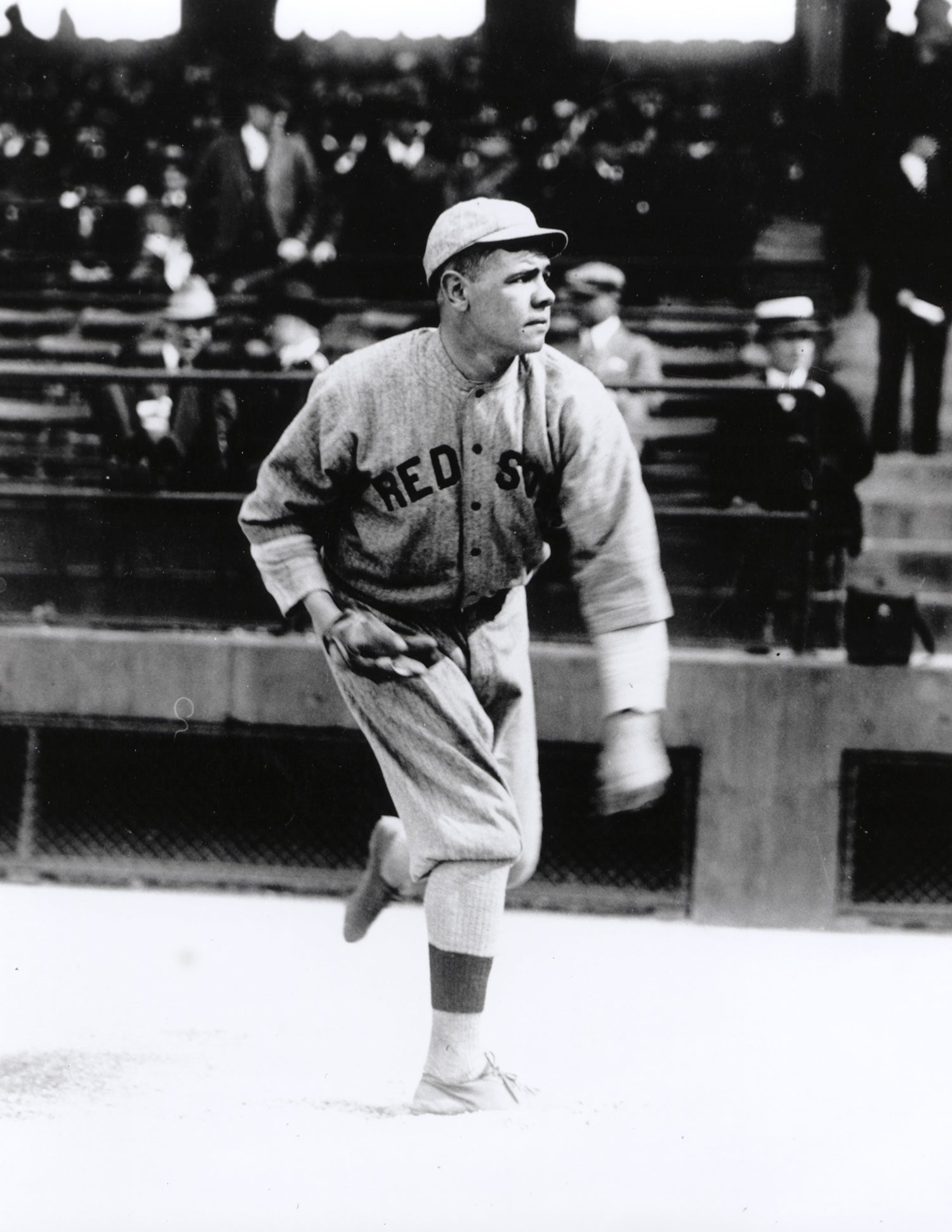

Using his professional playing experience for observation, Mann focused on the qualities necessary to develop fundamentals. Mann created films to demonstrate correct and incorrect ways to play, enlisting the help of more than 85 professional baseball players, including future Hall of Famers such as Rogers Hornsby, Max Carey, Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, and Tris Speaker.

In 1925, Mann began assembling the player footage along with titles and captions. These films were a way to build baseball skills by highlighting the finer details of batting, base running, sliding, pitching, defensive play and coaching. The instructional films consisted of 16 sections, each containing 40 minutes of material to develop a particular ability. Mann used 35mm cellulose nitrate film, which was standard at the time – yielding a higher quality image than the more economical 16mm.

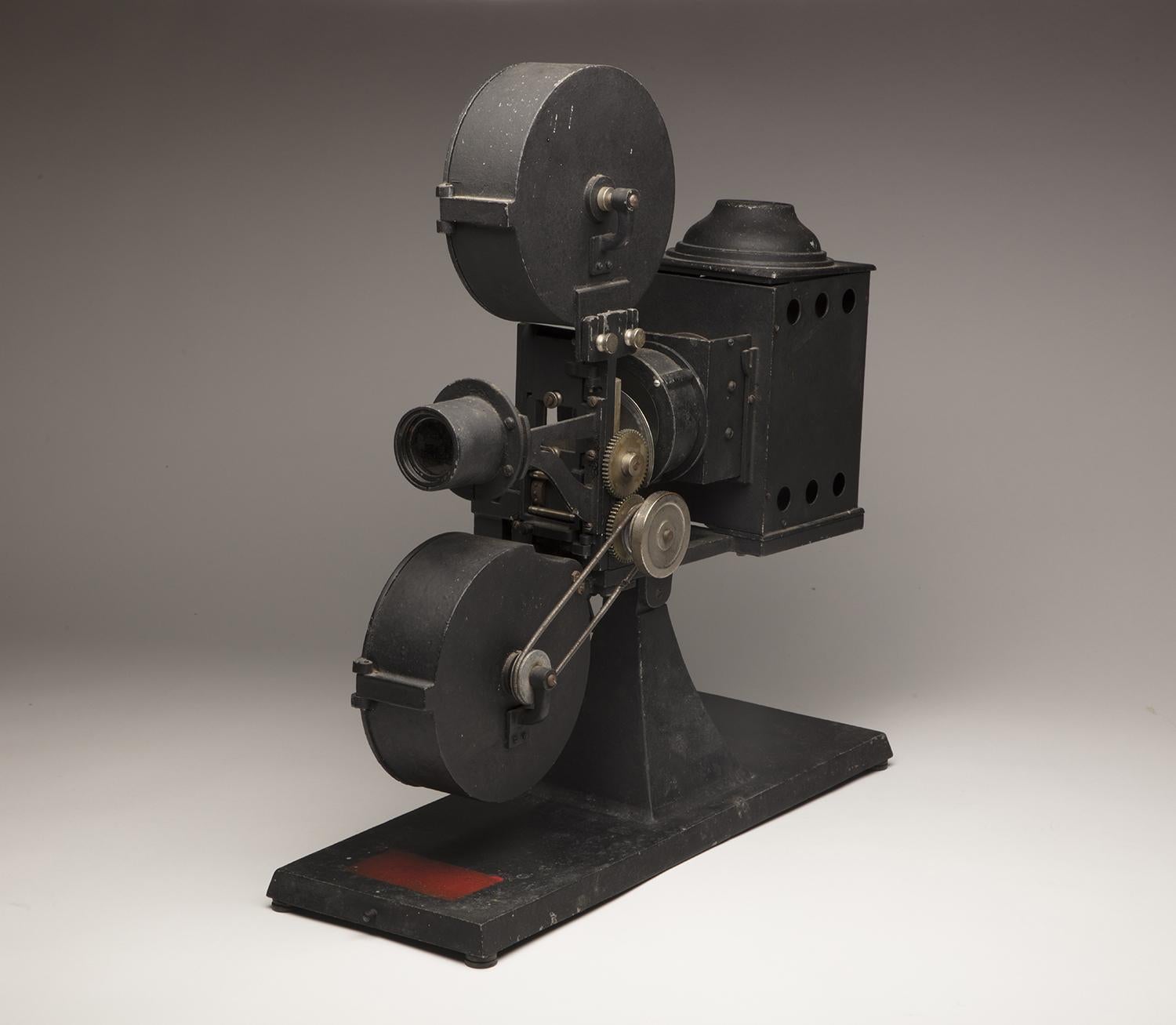

However, Mann decided it was not enough to develop only film content. He wanted to be able to play the reels in super slow motion, advance a frame at a time, pause, and reverse. Since these features were not readily available, he invented a new projector.

Patented on Oct. 11, 1927, the Mannscope was a combination motion picture and lantern projection machine. Rather than having an electric motor, the manually-operated machine could work in either continuous motion or be held stationary.

According to the patent: “The operator is then given plenty of time to thoroughly explain each play or movement shown on the screen before passing to the next one.” While held in a fixed position, the Mannscope contained water enclosed by two glass discs with a vent, which served as a cooling device, and prevented the radiating heat of the electric lamp from damaging the film.

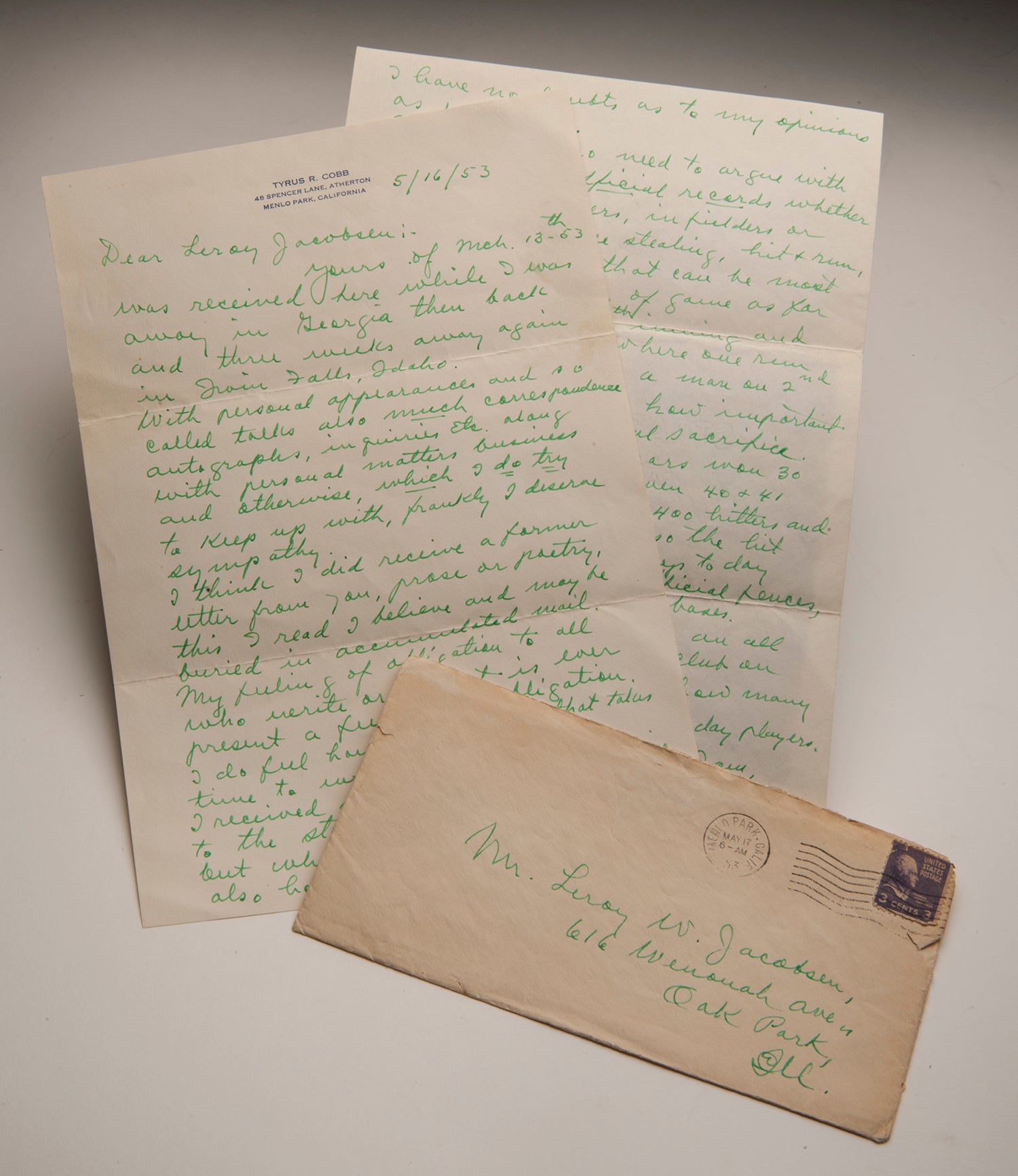

One of the earliest uses of film as a baseball training tool was popularized by Les Mann, whose Mannscope camera allowed moving pictures to be slowed for analysis without damaging the film itself. A version of the Mannscope was recently donated to the Hall of Fame. (Milo Stewart Jr. / National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

The Mannscope was not mass-produced; rather Mann marketed it personally. While on the road during his final big seasons of 1927 and 1928 with the New York Giants, he used his films and projector for lectures at high schools and colleges. After his playing career, he continued to devote time to expanding and building the amateur game by utilizing the films. The owners of the National and American Leagues hired Mann to tour the United States to publicize amateur development in 1929.

As the secretary treasurer for the National Amateur Athletic Federation in 1931, Mann announced the formation of the United States Amateur Baseball Association (later known as the United States Baseball Congress). The organization’s chief goal was to sponsor an international baseball tournament. In October 1935, Mann traveled with an amateur team to Japan. As the world prepared for the next great war, Mann continued to popularize the game in small tournaments in Great Britain and Cuba. During World War II, Mann served as the USO director of athletics in Hawaii.

Through his work with the USABA, Mann introduced baseball to 27 countries between 1931 and 1943. “We have them thinking, promoting, and playing our great game. Let’s be sure not to lose them now,” Mann wrote in a report to the NAAF. Mann continued working to expand and develop amateur sports throughout his lifetime.

Springfield College offered a Baseball Instructional Course in 1935 for freshmen, sophomores and coaches based on Mann’s films. However, the use of film for the instruction of baseball fundamentals, while widely accepted, had a slower expansion than the game itself. During the 1940s, the National League sponsored a film bureau, which produced a series of films that combined fundamental instruction with promotional material. The 30-minute films targeted colleges, amateur clubs and Latin American countries.

After an interview in 1927, the Allentown, Pa., Morning Call said: “In the long run we would say that a fellow like Mann will do as much even as a Babe Ruth to further the great national game.” While the Morning Call may have missed with its prediction, Mann’s invention gave the sporting world a new tool. His character and his desire to teach and expand the game built part of the foundation for training and analytical video systems used today.

Meghan Anderson was the 2017 curatorial intern in the Hall of Fame’s Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Youth Leadership Development