- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Ladies Day promotions gave women the chance to cheer

#Shortstops: Ladies Day promotions gave women the chance to cheer

Ladies Day was a popular marketing campaign in the 1920s and 1930s that offered free entry into professional baseball games for women 16 or older.

It was particularly successful at Wrigley Field, and spread across Major League Baseball into the 1980s.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Ladies Days existed as early as the 1880s, but gained popularity after World War I. The 19th century Ladies Days promotions required women to bring a male chaperone. But even with a lack of clause requiring a male chaperone in later Ladies Day games, the general idea of the promotion persisted in that women would bring a male significant other; the man’s paying ticket would compensate for the woman’s complimentary one.

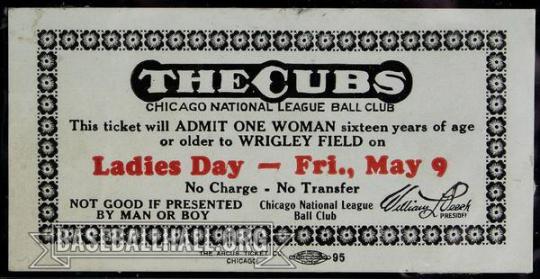

But promoters failed to foresee just how successful Ladies Day would become. So successful, in fact, that women would bring their female friends along instead of the intended boyfriends. The 1929 Chicago Cubs season saw more than 200,000 Ladies Day participants. The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s collection contains a Wrigley Field Ladies Day ticket from May 9, 1930.

In one instance, a Ladies Day promotion at Wrigley Field saw a crowd of 33,000, as opposed to 12,000 the day before. Upon realizing the success of Ladies Day, the Cubs’ management at Wrigley Field began to limit the number of tickets given to women for free. This was an effort to, “...Keep feminine guests from taking over the premises en toto to the exclusion of paying patrons.”

Although Ladies Day promotions were extremely successful, they began to garner negative criticism. Newspapers published unflattering cartoons and mirthless jokes of women cheering at the wrong time during games, implying that women could not grasp the intricacies of baseball. Other articles attempted to support the female fans of Ladies Day. However, many of these articles still conveyed condescending messages such as, “...it seems to us that there is currently less cheering at the wrong times than formerly.”

Some male spectators at Ladies Day games complained that women stood during inappropriate times, and demonstrated too much enthusiasm. These arbitrary complaints – many unsubstantiated – were often designed to keep female spectators from feeling like true fans. Other articles described alleged instances of women throwing their shoes at umpires, or getting into scuffles in the stands, as ways of discrediting the female fan experience. If true, these instances were few and far in between, and almost seem quaint by the current standard of fan behavior.

Ladies Day promotions also became an opportunity to comment on the appearances of female fans. Women could gain admission if they, “...smiled and looked pretty”. Ballparks also started to partner with businesses to offer free nylons on Ladies Days. Wrigley Field, which was overwhelmed by the success of the promotion, tried to curtail the female crowds by encouraging retailers to begin their own Ladies Day campaigns on game days. This was an attempt to lure women away from ballparks and into shopping centers.

Unfortunately, women were also accused of neglecting their duties at home by visiting the ballpark. One article claimed, “…some women are more loyal indeed to the team than they are to the old man who probably is at home wondering when in heck when he’s going to get his dinner.”

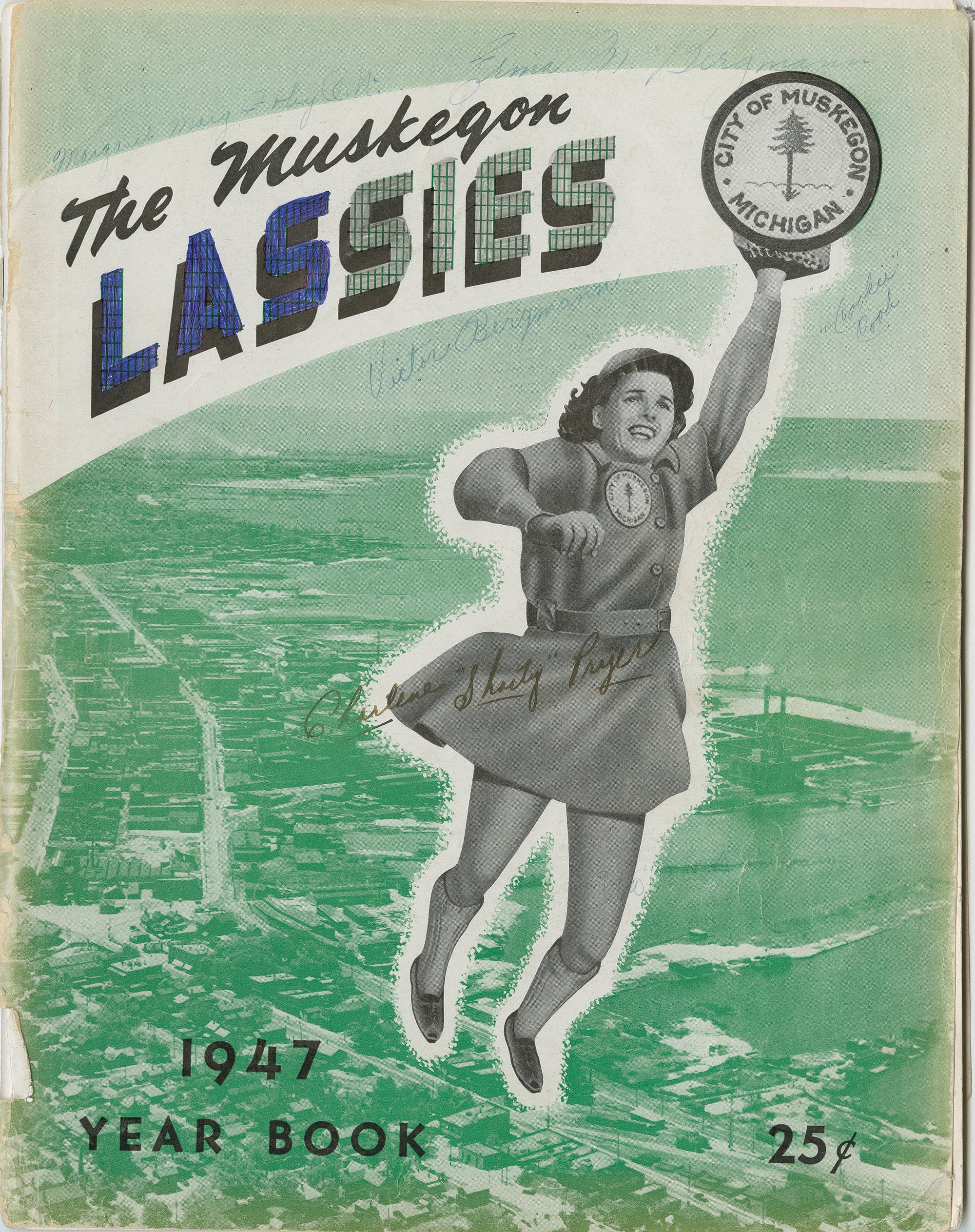

But despite the discouragement from newspapers, disgruntled men, and even the ballparks themselves, women continued to visit games and made Ladies Day promotions successful for decades to come.

Ladies Day promotions persisted after World War II and through the Civil Rights era, but were ultimately terminated in the 1980s due to a claim of reverse discrimination in Abosh v. New York Yankees. But the effects of the promotion can still be felt today with Major League Games seeing almost equal attendance by both men and women.

Although Ladies Day promotions yielded negative attention at times, the unprecedented popularity of the games proved that women desired a place in the ballpark just as much as the men. The women who asserted their right to visit a ballpark reflected the greater fight for equal rights in American Culture.

Jessica Hollister was the 2018 photo archives intern in the Hall of Fame’s Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Youth Leadership Development