- Home

- Our Stories

- League of Women Ballplayers

League of Women Ballplayers

“We would rather play ball than eat,” insisted catcher Lavonne “Pepper” Paire. “We put our hearts and souls into the league. We thought it was our job to do our best, because we were the All-American girls. We felt like we were keeping up our country’s morale.”

The history of women playing the game of baseball dates back to at least the 1860s, when Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, N.Y. fielded a team. Some 80 years later, arguably the first formal women’s professional baseball league, the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, first took the field.

The AAGPBL, which began play in 1943 and lasted a dozen years and gave more than 500 women an opportunity that had never existed before. Popularized by the 1992 feature film A League of Their Own (“There’s no crying in baseball!”), the so-called “lipstick league” was the brainchild of Chicago Cubs owner Philip K. Wrigley as a way to keep the ballparks busy during World War II if manpower shortages threatened big league baseball.

“It is impossible to make any statement on a softball league at this time because there may not be any league,” said Cubs general manager James Gallagher in January 1943. “That’s just one of the many projects we’re considering so as to be ready for eventualities. Wrigley Field is a big plant and we have to figure out what we’re going to do with it under varying circumstances. We have many ideas – which include even light opera.”

The women’s league, however, quickly became a reality. The new league’s first tryouts were scheduled for Chicago in the spring of 1943 and drew almost 300 women from across the United States and Canada.

“The need for additional recreation in towns busy with war defense work prompted the idea,” said Wrigley.

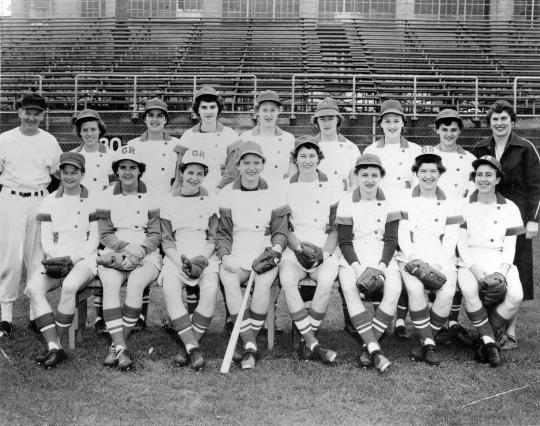

Though it began as a women’s professional softball league, rules were soon modified and the All-American Girls Baseball League (later to be known as the AAGPBL) was born when four Midwest teams - the Rockford Peaches, the South Bend Blue Sox, the Racine Belles and the Kenosha Comets – played a 108-game schedule.

The AAGPBL at times included the Fort Wayne Daisies, Minneapolis Millerettes, Kalamazoo Lassies, Muskegon Lassies, Grand Rapids Chicks, Peoria Redwings, Milwaukee Chicks, Chicago Colleens and Springfield

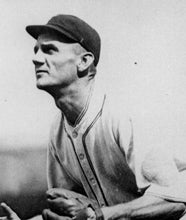

Former big league players such as Hall of Famer Jimmie Foxx, Johnny Rawlings, Bert Niehoff, Josh Billings, Leo Murphy, Bill Wambsganss and Dave Bancroft served as managers in the league, while Hall of Famer Max Carey was its president.

“Femininity is the keynote of our league; no pants-wearing, tough-talking female softballer will play on any of our four teams,” Carey said.

“Every day after practice, Mr. Wrigley sent us to Helena Rubinstein’s charm school to learn how to put on makeup, how to put on a coat, and how to get in and out of a car or chair,” said Lil Jackson. “Back at the hotel, he made us wear skirts. If you dressed in slacks, you had to use the servants’ elevator.”

Though the players wore short skirts as part of their uniforms, the AAGPBL lasted for more than a decade because it relied on players’ skills to draw fans to the ballpark. Attendance rose steadily during the early years of the league, topping out at around 1 million fans in 1948.

“We have some glamour pusses, but most of us are just white collar girls who stopped wearing collars,” said one unnamed young lady. “Me, I’m strictly the fresh, wholesome type. If the customers were interested in legs instead of arms, you’d never see me in the lineup.”

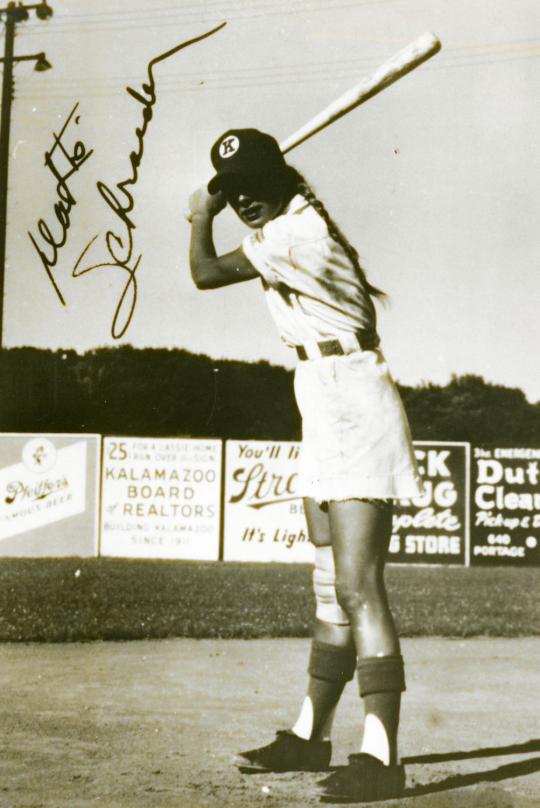

The Cubs manager in the mid-1940s, Charley Grimm, said of Kenosha shortstop Dottie Schroeder, “I’d pay $50,000 for her if she were a boy.”

Eventually, with the end of WWII and the rise of televised major league games, among other issues, led to the demise of the AAGPBL.

“When we were playing, we didn’t realize what we had,” said Daisy pitcher Dottie Collins years later. “We were just a bunch of young kids doing what we liked best. But most of us recognize now that those were the most meaningful days of our lives.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum