“He’s 42 and I’m 25, and you can’t take me out until that man is not pitching.”

- Home

- Our Stories

- Hall of Fame Matchup

Hall of Fame Matchup

In retrospect, we might have expected a Hall of Fame pitching duel between future immortals Juan Marichal of the San Francisco Giants and Warren Spahn of the Milwaukee Braves on July 2, 1963.

Normally a slow starter, Spahn, 11-3 with a 3.12 earned run average, hadn’t allowed a walk in 18 1/3 innings and was facing the same eight position players he’d no-hit in 1961.

Marichal, 12-3 with a 2.38 ERA, had won eight straight and no-hit Houston just 17 days earlier. Moreover, they could not have asked for a better locale. Candlestick Park was invariably chilly, because the wind came off San Francisco Bay. Balls don’t carry as far in cold weather as they do when it’s warm, and hitters don’t fare as well when it’s cold. Finally, the strike zone, enlarged before the 1963 season, now measured from the bottoms of the knees to shoulder level.

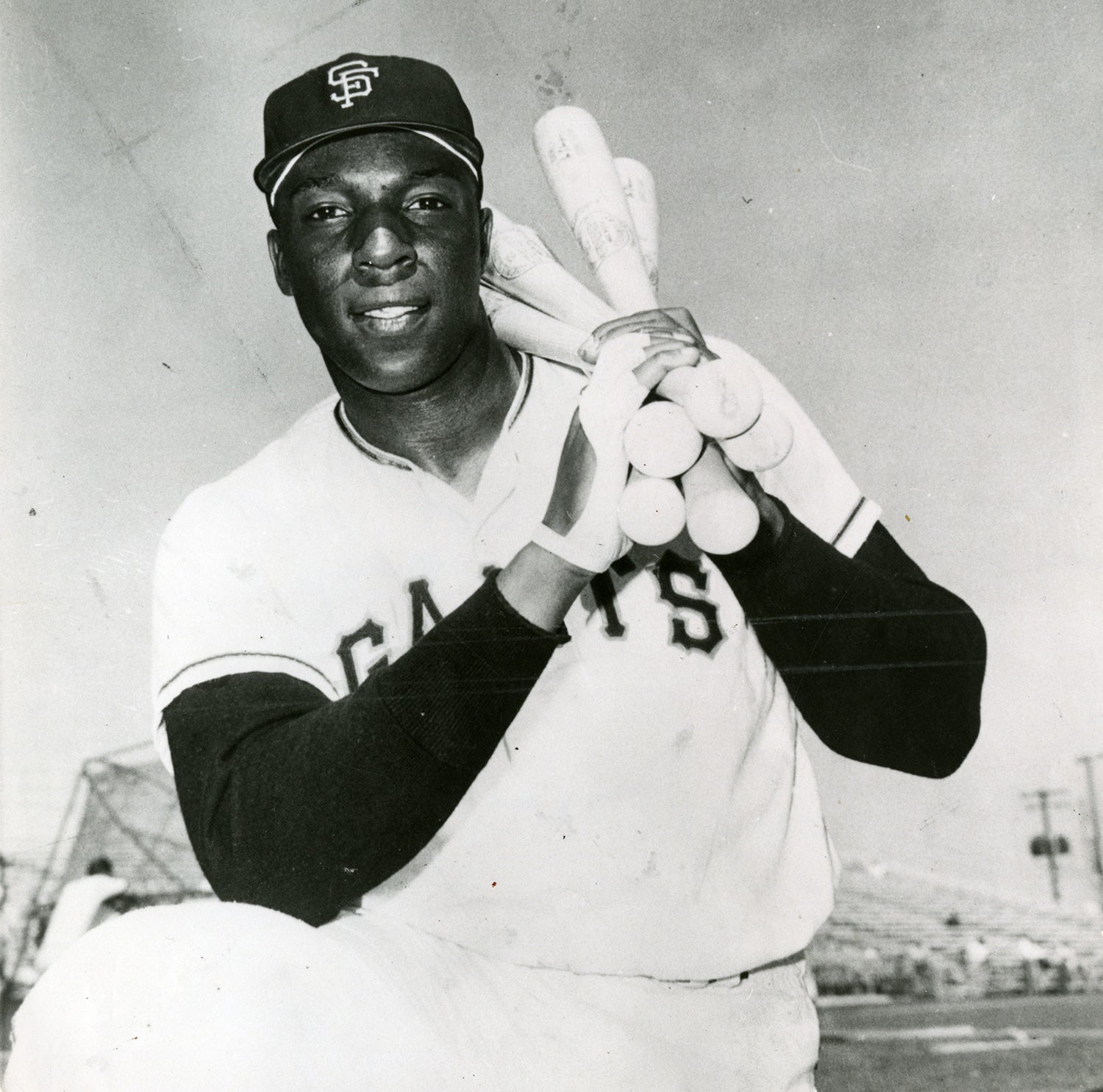

Even so, what Spahn and Marichal accomplished that night was off the charts. Despite five other future Hall of Famers in the lineups — Hank Aaron and Eddie Mathews of the Braves; Orlando Cepeda, Willie Mays and Willie McCovey of the Giants — Spahn and Marichal threw more than 200 pitches apiece. They fought into the 16th inning and the next morning before a Hall of Fame moment ended the tilt with a single run before 15,921 exhausted fans.

It was arguably The Greatest Game Ever Pitched.

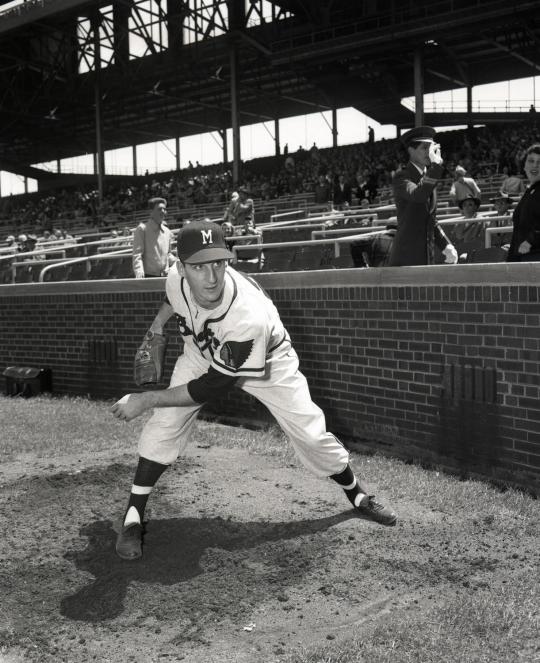

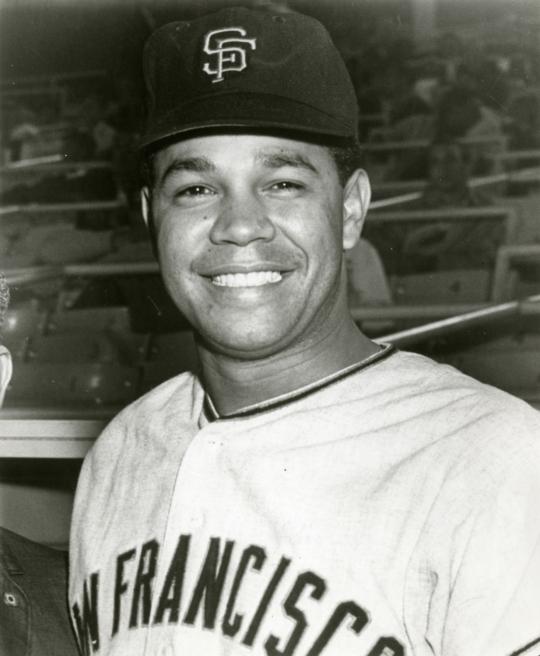

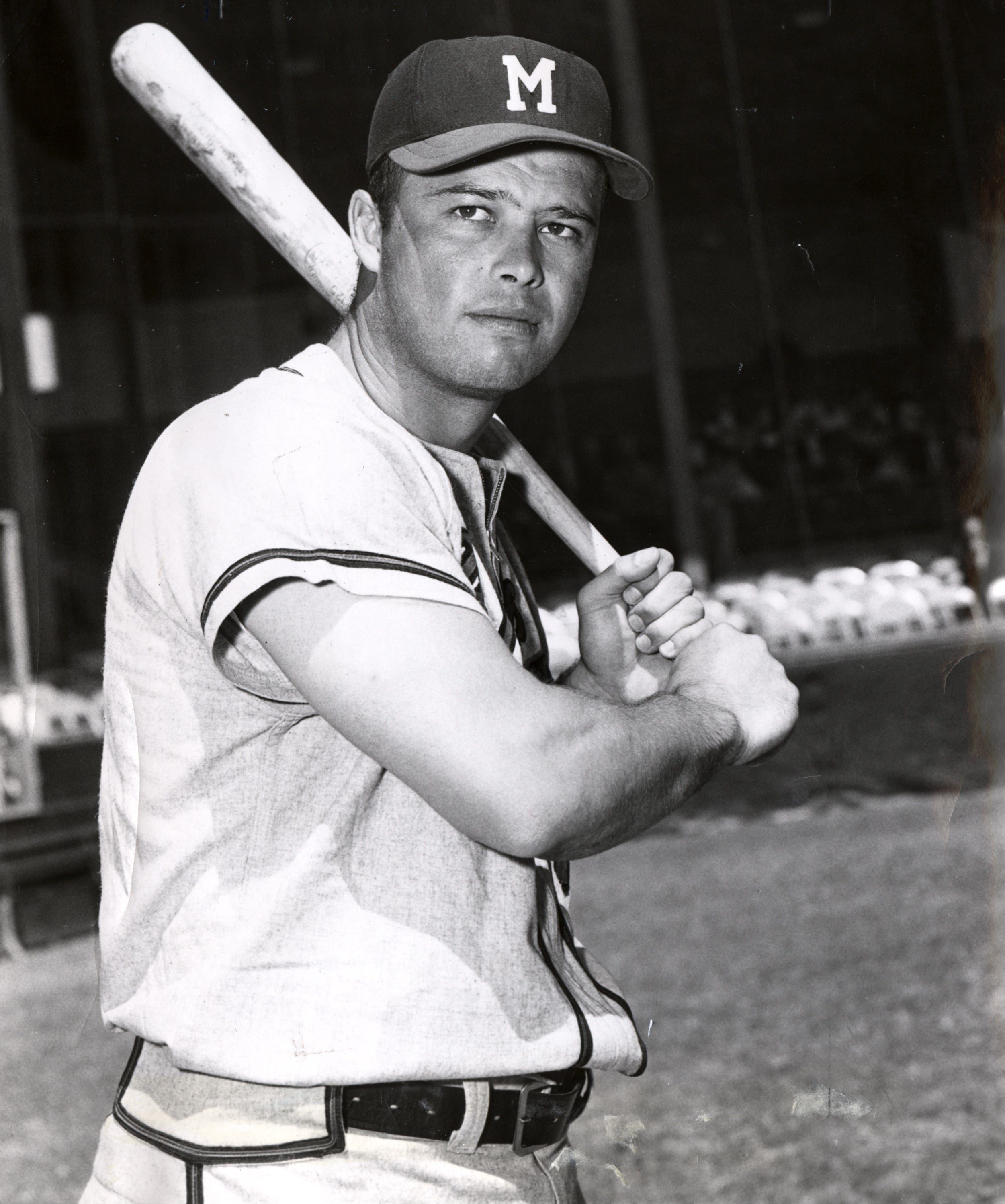

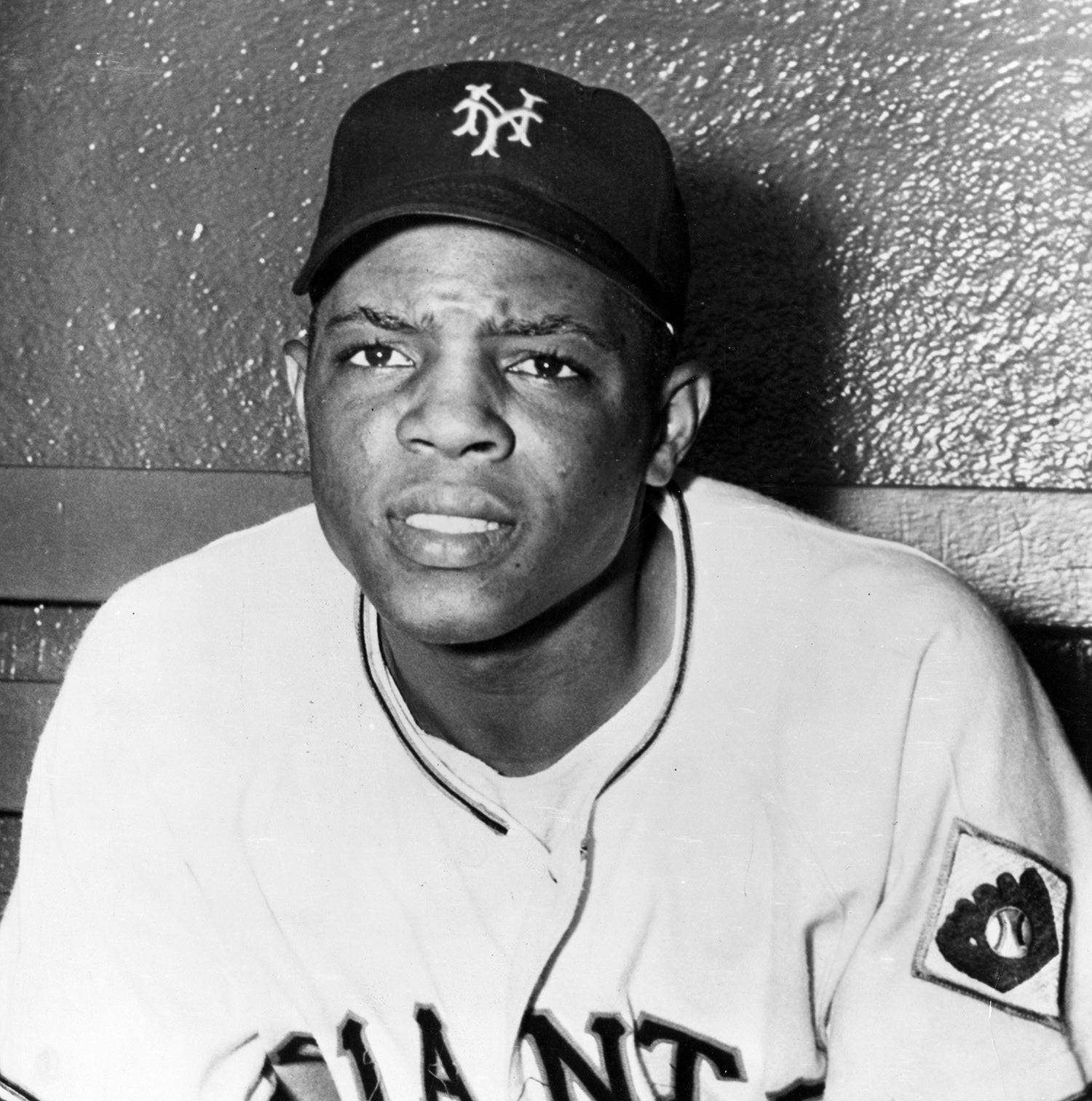

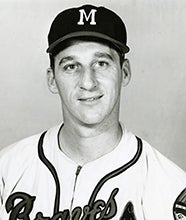

Marichal and Spahn, Juan and Warren, Manito and Hooknose – they were at once very different yet much the same. An American and a World War II hero, Spahn, who was 42 at the time, was left-handed, with a receding hairline and a conspicuous nose that earned him several nicknames, Hooks being the most prominent.

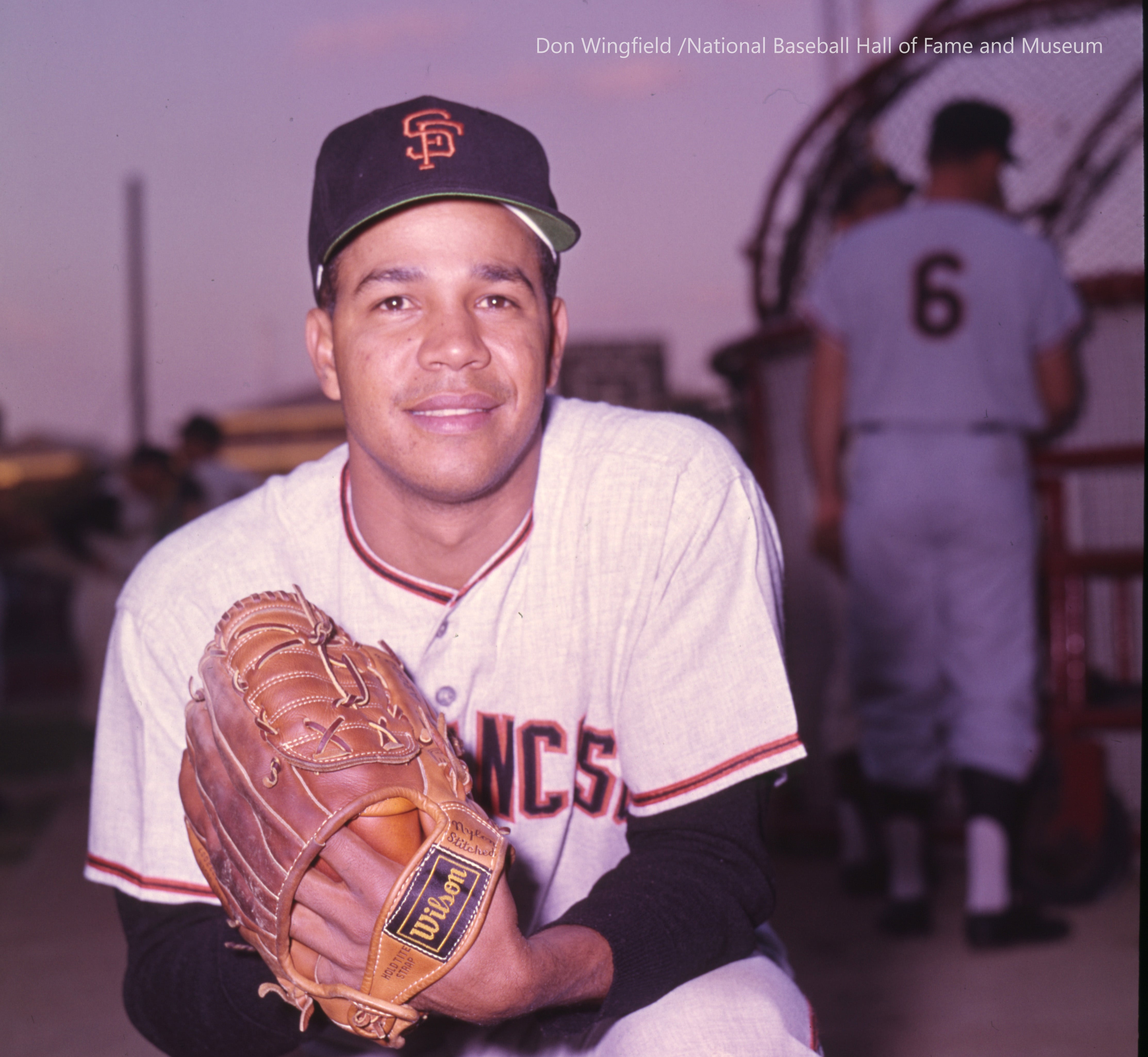

A right-handed Dominican who served in his country’s military, Marichal was 25 with a full head of hair and a round face with proportionate nose – and cheeks so full that teammate Eddie Bressoud dubbed him Popeye. He was also called Laughing Boy and, because of his light blue and cream-colored outfits, the Dominican Dandy — nicknames that forecast a more emotive, multicultural national pastime.

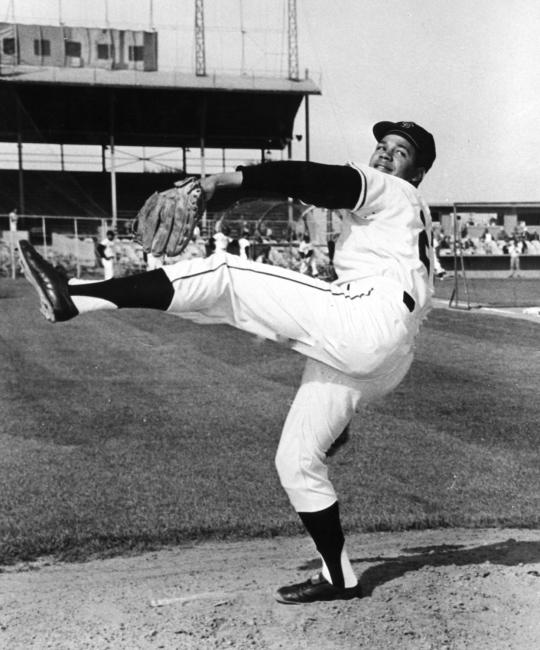

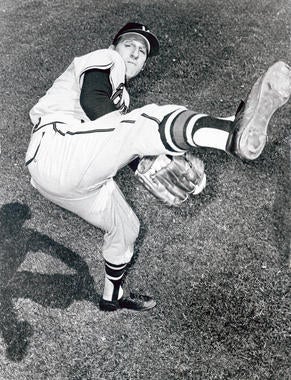

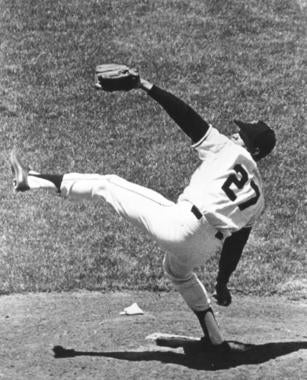

Yet Juan and Spahn had much in common. They were an inch or two taller than most pitchers of their time — Marichal at six feet and 180 pounds, Spahn at six feet and 172 pounds — and both used signature, high-kicking deliveries that made their release points hard to pick up. Each threw an impressive variety of pitches and extended their careers by mastering the screwball. Moreover, both their life stories included formative experiences with a relative and the military.

Growing up in the farm community of Laguna Verde, young Juan would ride a horse to Monte Cristi six miles away to watch his older brother Gonzalo play baseball, then ride behind him on the horse and pepper him with questions on the way home. Juan might have become just a good local pitcher were it not for the day when he pitched the Manzanillo team to a 2-1 win over Aviación, the Dominican Air Force nine, in the 1956 national amateur tournament. The next day he received a telegram reading, “Report Immediately to the Air Force team.” He had been drafted to play baseball.

His first assignment was to head to Santo Domingo’s Estadio Las Normal to qualify for a youth tournament in Mexico. After taking his first plane trip there, Juan won one game and saved another against Puerto Rico to reach the finals against the home team. There he and his teammates encountered fans with knives and guns sitting directly on top of their dugout. “When we went to the bullpen, they showed us their gun,” he says. “We were so scared, we couldn’t handle the pressure.” The Mexicans won. The Dominicans escaped. And Juan never again viewed pitching as particularly pressure-laden.

Young Warren Spahn grew up in Buffalo, N.Y., where his father Edward, a shipping clerk, wallpaper salesman and semipro baseball player, exhaustively taught him the game. Edward built Warren a mound in the back yard, and drilled him on the importance of control. He meant self-control as well as control over the strike zone. “Don’t pop off too much,” he told Warren. “The guy who is noisy, always blowing off, is the guy who has an inferiority complex. Be yourself, be polite, respect other people’s feelings and treat them with deference.”

After much schoolboy success, Warren was signed by the then-Boston Braves, pitched well in the minors and had a cup of coffee in Boston before enlisting for World War II. He eventually fought in the Battle of the Bulge and the fight over the bridge at Remagen, won a Purple Heart and a battlefield commission and returned to the majors as a mature 25-year-old.

Pitching? Pressure? “No one is shooting at me,” Spahn said.

And so Spahn and Marichal went to work on July 2, 1963. In a telling first inning, Marichal got Aaron on a foul to first and struck out Mathews, while Spahn got Mays on a called strike three and McCovey on a grounder to the mound. Four Hall of Famers, no balls out of the infield. Marichal was using his arsenal of pitches, perhaps most effectively his fastball. Spahn was spotting his fastball and subduing right-handers with his screwball and left-handers with his curve. Before the game went into extra innings, there was just one extra-base hit: Spahn’s double off the right-field fence.

Pitching classics often come with great fielding plays and some luck. With two outs in the Braves’ fourth and Norm Larker on second, Del Crandall singled to center for what looked like the game’s first run. But Mays fielded the ball on one hop and fired home to nail Larker on what San Francisco sportswriters called “one amazing motion” and a “100 percent perfect peg.” In the ninth, the Giants’ McCovey hit one of his patented moon shots over the right-field foul pole. Everyone thought it was a homer, except first base umpire Chris Pelekoudas, who ruled it a foul ball.

As the game went into extra innings, everyone knew something special was afoot. Sitting on a long bench down the left-field line in a San Francisco 49ers windbreaker, 19-year-old Giants rookie Al Stanek huddled with other relievers and bullpen catchers in what felt like a wind tunnel. Every once in a while, a reliever got up to throw, but only to stay warm. “The feeling was that we’ll be here for a long time,” Stanek said.

While the Giants hit, Marichal sat on the bench chewing Bazooka bubblegum and studying Spahn. Neither man wanted to be relieved. “Alvin, do you see that man pitching on the other side?” Marichal told Giants manager Alvin Dark. “He’s 42 and I’m 25, and you can’t take me out until that man is not pitching.”

Only defeat could bench that man Spahn. With one out in the Giants’ 16th, Spahn threw a screwball to Mays. The pitch hung. Mays swung. The ball headed over the head of third baseman Denis Menke, climbing inexorably, fighting the wind. At 12:31 a.m. on July 3, it crossed the fence after an eon in the cold night sky. Giants 1, Braves 0. The crowd rose and cheered: For the Giants win, for Marichal, for Spahn and for their own fortitude.

“JUAN BEATS SPAHN,” blared a front-page San Francisco Chronicle headline. Ron Fimrite, later a Sports Illustrated legend, then a news-side Chronicle reporter at the park on a night off, wrote in an SI retrospective, “There were lesser Page One stories that day — something about a nuclear test ban and the FBI smashing a Soviet spy ring. But for one day at least, an epic pitching duel dominated the news. It was, I told the guys in the office, a rare exercise of sound editorial judgment.”

The Greatest Game Ever Pitched deserved no less.

Jim Kaplan is the author of The Greatest Game Ever Pitched: Juan Marichal, Warren Spahn and the Pitching Duel of the Century, and lives in Northampton, Mass.