- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1984 Donruss Frank White

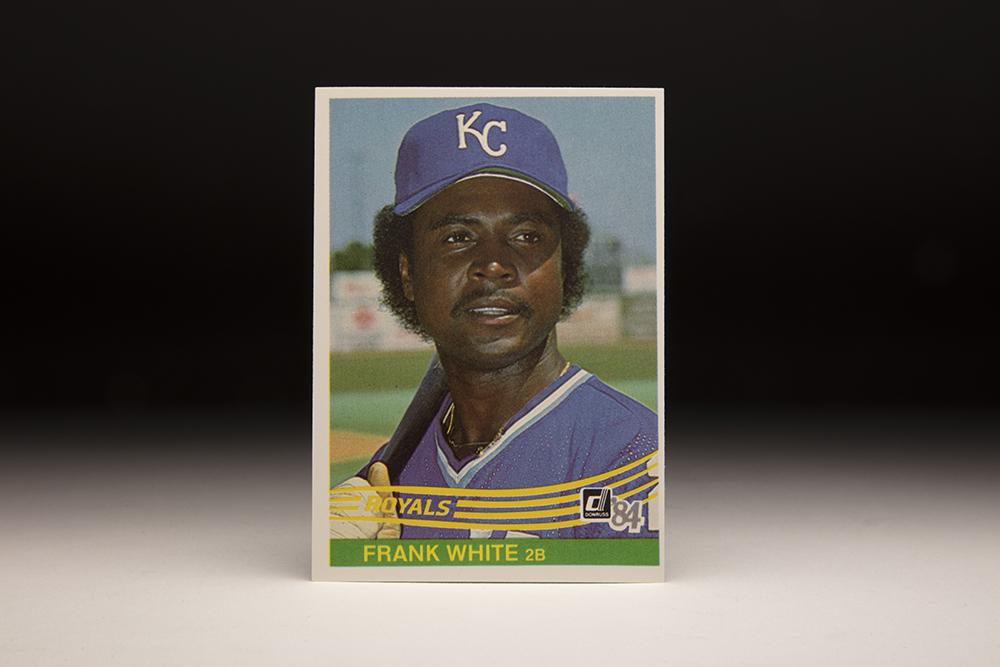

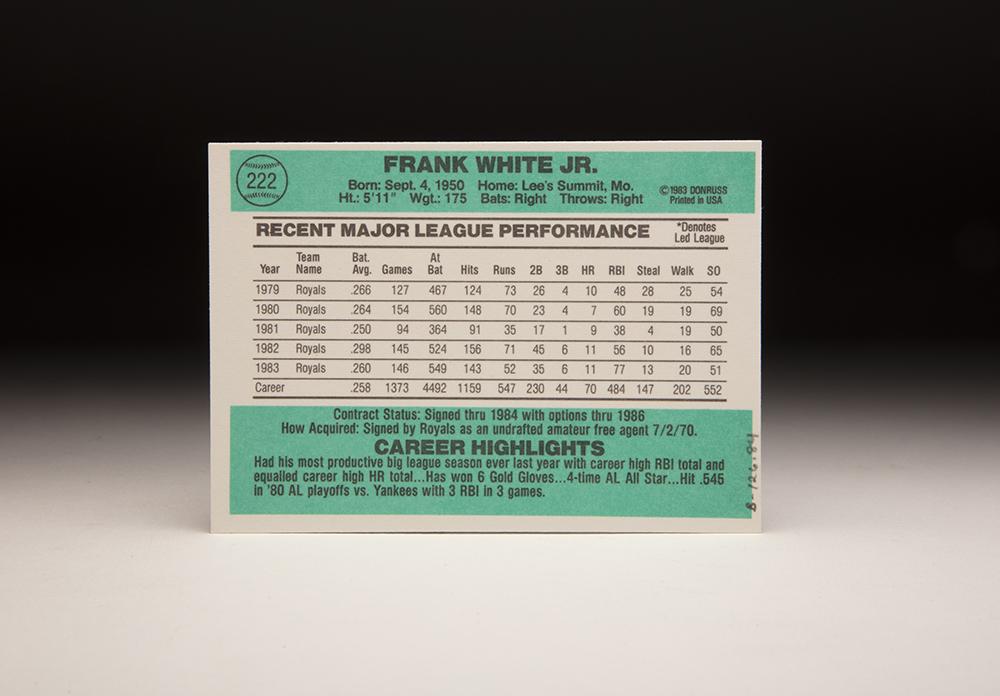

#CardCorner: 1984 Donruss Frank White

On Oct. 19, 1985, Kansas City Royals manager Dick Howser penciled in second baseman Frank White as the team’s cleanup hitter in Game 1 of the World Series against the Cardinals.

In the 81 World Series previously contested, one second baseman – Jackie Robinson in four different years – had ever batted out of the No. 4 spot.

For White, it was an honor he never expected.

“I visualized Missouri having a Royals-Cardinals World Series someday,” White, who grew up in Kansas City, told The New York Times. “But I never thought I’d be batting cleanup in it.”

After seven games with White batting in what was then baseball’s premier run-producing spot, the Royals were world champions. It was the pinnacle of an 18-year big league career in which White became one of the most respected players in the game.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Born Sept. 4, 1950, in Greenville, Miss., Frank White Jr. was the son of a Negro Leagues ballplayer. The family moved to Kansas City when White entered school, and he attended Lincoln High School – located a few blocks from old Municipal Stadium where the Kansas City Athletics played.

“I saw a lot of stars play (at Municipal Stadium),” White told the Associated Press of his days when he’d watch games from the football bleachers at his high school, which was located right next to the Athletics’ stadium. “And I had two idols: Hank Aaron and Jackie Robinson. I never saw Robinson but I always admired the things he stood for and what he accomplished.”

An all-around athlete, White played sandlot ball – Lincoln High School did not field a baseball team – and starred for his school’s football and basketball teams. White was already married and working as a shipping clerk in 1970 when he impressed the Royals at a tryout camp – his wife, Gladys, encouraged him to go – earning an invitation to the groundbreaking Royals Academy in Sarasota, Fla.

He would become the first graduate of the Academy to make the big leagues.

Debuting with the Royals’ team in the Gulf Coast League in 1971, White was then a shortstop. He played at the Class A and Double-A level in 1972, appearing in 140 games while hitting a combined .267 with 24 stolen bases for San Jose and Jacksonville. The Royals promoted White to Triple-A Omaha and moved him to second base in 1973 – and he was called up to Kansas City in June when shortstop Freddie Patek went on the disabled list.

“No, I didn’t think when I went to the Academy I’d ever play with Kansas City,” White told the Associated Press during his rookie season. “I always hoped.

“I’ve already found out one thing: I can play defense up here.”

White hit .223 in 51 games with the Royals in 1973 and made the team’s Opening Day roster in 1974 as a utility infielder, hitting .221 in 99 games. He reprised that role in 1975 before taking over for the popular Cookie Rojas at second base in September, finishing the year with a .250 batting average in 111 games.

“I hated it when I first started playing here,” White told the Kansas City Star in 1980. “I didn’t think (the fans) gave me a fair chance when I replaced Cookie. What they didn’t realize was it was obvious to any player that Cookie’s playing days were over. I just happened to be the guy who replaced him.”

Rojas, ironically, became one of White’s biggest supporters.

“There isn’t any better second baseman in the league than Frank,” Rojas said during the transition. “Range, nobody can touch Frank. Tremendous hands. He has the smoothness, the agility you don’t find in many infielders.”

Now entrenched at second base, White played in 152 games in 1976 as the Royals won the American League West for the first time. He batted just .229 with 46 RBI and 39 runs scored but posted a defensive WAR of 2.5, the sixth-best figure among all players in the AL. In the postseason, White and Rojas shared time at second base, with White starting Games 1, 2 and 3 against the Yankees while Rojas started Games 4 and 5. The Yankees won the series on Chris Chambliss’ walk-off home run.

The next season, the Royals won 102 games to repeat as AL West champions. White improved his batting average to .245 with 50 RBI and 59 runs scored while winning the first of eight Gold Glove Awards – including six in a row. He also led all AL second basemen in fielding percentage with a .989 mark, the first of three times he would lead the league in that category.

But once again, the Yankees defeated Kansas City in the American League Championship Series.

“I think in ’77 we had our best ballclub,” White told The New York Times. “But we didn’t have the pitching.”

In 1978, White hit .275 with 50 RBI and 66 runs scored and was widely considered to be one of the best second basemen in the game. He earned his first All-Star Game selection and once again helped the Royals to a division championship. And again, Kansas City fell to New York in October.

Still, White and his Kansas City teammates were now baseball royalty. And White’s bat had virtually caught up with his sensational glove.

“When I first came up, (Royals manager) Whitey (Herzog) used to pinch hit for me,” White said. “But in ’78, it changed.”

White was named to his second All-Star Game in 1979, this time earning the starting nod. But he played in only 127 games that season after suffering a broken hand when he was hit by an Ed Farmer pitch in May. Still, White batted .266 with 10 homers, 48 RBI and 28 steals while scoring 73 runs, which would be his high-water mark until 1986. The Royals, however, failed to win the AL West for the first time since 1975 – and Herzog was replaced by Jim Frey for the 1980 season. It would be a year that would see the Royals come within two wins of a world championship.

White had his best offensive season to date in 1980, batting .264 with seven home runs, 60 RBI and 19 steals. He did not repeat as an All-Star but did win his fourth straight Gold Glove Award. More importantly, the Royals recaptured the AL West title. And in the ALCS, the Royals swept the Yankees – with White winning Most Valuable Player honors after going 6-for-11 with three runs scored and three RBI. His fifth-inning home run in Game 3 broke a scoreless tie and helped propel the Royals to a 4-2 victory that wrapped up the series.

White and shortstop U.L. Washington – both graduates of the Royals Academy – formed an airtight infield defense that was the envy of almost every team in baseball.

“I was telling U.L. that we are probably the two most unlikely people to play in the World Series,” White told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch before Game 1 of the Fall Classic against the Phillies. “If the Academy had not been around, we couldn’t have played baseball.”

But the World Series did not prove much fun for White, who went 2-for-25 at the plate as Philadelphia won the title in six games.

The Royals returned to the postseason in 1981 as the second half winners of the AL West but were swept in the Division Series by the Athletics. White returned to the All-Star Game that year and was even better in 1982 when he hit .298 with 11 homers, 45 doubles and 56 RBI while winning his sixth straight Gold Glove Award on the strength of his league-leading 361 putouts at second base.

But the team began transitioning away from the core of players that made it so successful in the late 1970s, and in 1983 Kansas City finished with a losing record for the first time in a full season since 1974. White, however, was named the team’s Player of the Year after hitting .260 with 11 homers and 77 RBI. But despite leading all big league second basemen with a .990 fielding percentage, White was not rewarded with a Gold Glove Award.

In 1984, however, the Royals returned to the postseason despite White missing 28 games in late June and early July due to a pulled hamstring. White finished the year with a .271 batting average, 17 homers and 56 RBI – showing early signs of his late-career power surge. The Royals, meanwhile, won the AL West but were swept by the Tigers in the ALCS.

But in 1985, it all came together for Kansas City. The Royals repeated as AL West winners with White – who signed a multi-year contract extension that spring – hitting .249 with 22 homers and 69 RBI. White also led AL second basemen in assists for the first time with 490, providing stability for a young rotation that featured 22-year-old Mark Gubizca, 23-year-old Danny Jackson and 21-year-old Bret Saberhagen, who would go on to win the AL Cy Young Award.

Then there was closer Dan Quisenberry, whose submarine delivery produced grounders that White turned into outs.

“That was my goal in life,” Quisenberry told the Kansas City Star. “Eat three meals. Get eight hours of sleep. And have the ball hit somewhere near Frank.”

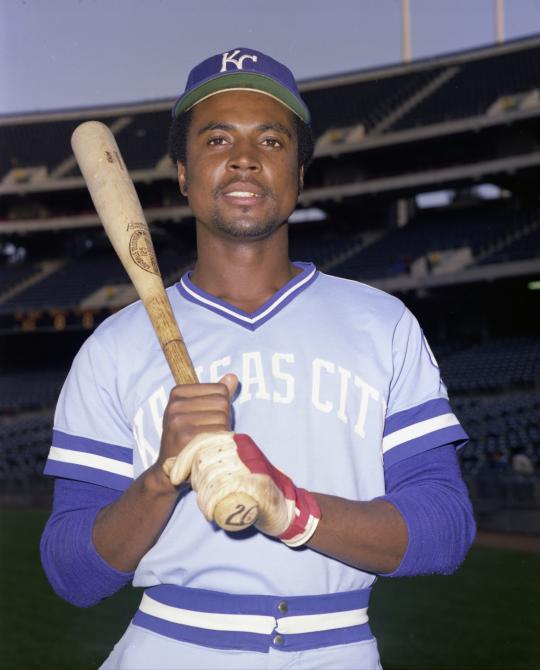

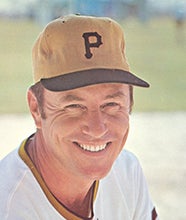

In the spring of 1985, Frank White signed a multi-year contract extension with the Royals. Then, he hit .249 with 22 homers and 69 RBI as Kansas City repeated as AL West winners and won the first World Series title in franchise history. (Doug McWilliams/National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Batting all over the lineup in the ALCS vs. Toronto – including the No. 8 slot in Games 6 and 7 – White hit just .200 but produced an RBI single in the deciding Game 7. Then the World Series – with designated hitter Hal McRae unavailable under the format where the DH was used in even-numbered years only – manager Dick Howser moved White into the cleanup spot.

White responded with three hits in Game 2, three RBI in Game 3 and RBIs in Games 5 and 7 as Kansas City defeated St. Louis for the title. His six RBI in the series were the most of any player on either team.

White parlayed the World Series momentum into a spectacular season in 1986 when he hit .272 with 27 doubles and 22 homers to go along with career-highs in runs scored (76) and RBI (84). He returned to the All-Star Game for the first time since 1982, captured his seventh Gold Glove Award and won a Silver Slugger Award. For his efforts, he was named the Royals Player of the Year for the second time.

In 1987, White won his eighth Gold Glove Award, tying Bill Mazeroski for the most ever among second baseman to date, and continued his clutch hitting with 17 homers and 78 RBI. He began to show signs of age the following year, however, when at age 37 he hit .235 with eight homers and 58 RBI. But his defense was strong as ever in 1988, as White led all MLB second basemen with a .994 fielding percentage. But the AL Gold Glove Award went to Harold Reynolds, denying White a ninth Gold Glove that would have put him alone at the top of the list (Roberto Alomar, 10, and Ryne Sandberg, with nine, have since topped White and Mazeroski).

“I’m disappointed because it was so obvious,” White said after learning he did not win the Gold Glove. “It wasn’t obvious only to me, but all those who watched me. I think I’m the best second baseman in baseball.”

Even at that late stage of his career, few would have disagreed.

White and teammate George Brett were named Royals co-captains in the spring of 1989 – but that season proved to be White’s last as a regular. He hit .256 in 135 games that year but saw his home run total drop to two. Then in 1990, White hit .216 in 82 games in a reserve role.

On Oct. 25, 1990, the Royals announced they would not offer White a contract for the 1991 season. White soon retired, receiving plaudits from teammates and opponents throughout the game.

“One thing I’m proudest of,” White told the Kansas City Star, “is that I’ve taken great care of my name.”

White finished with 2.006 hits, 407 doubles, 160 home runs and 886 RBI. His career totals of putouts (4,742) and assists (6,253) each rank 12th all-time in big league history.

“Frank’s defense is what everyone talks about,” John Wathan, White’s teammate and manager, told the Kansas City Star in 1990. “Sometimes you wondered how he even got to balls, much less throw somebody out.

“But people thought he’d be a .230 or .240 hitter when he came up. Then he drove in a lot of runs and wound up batting fourth in the World Series.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum