- Home

- Our Stories

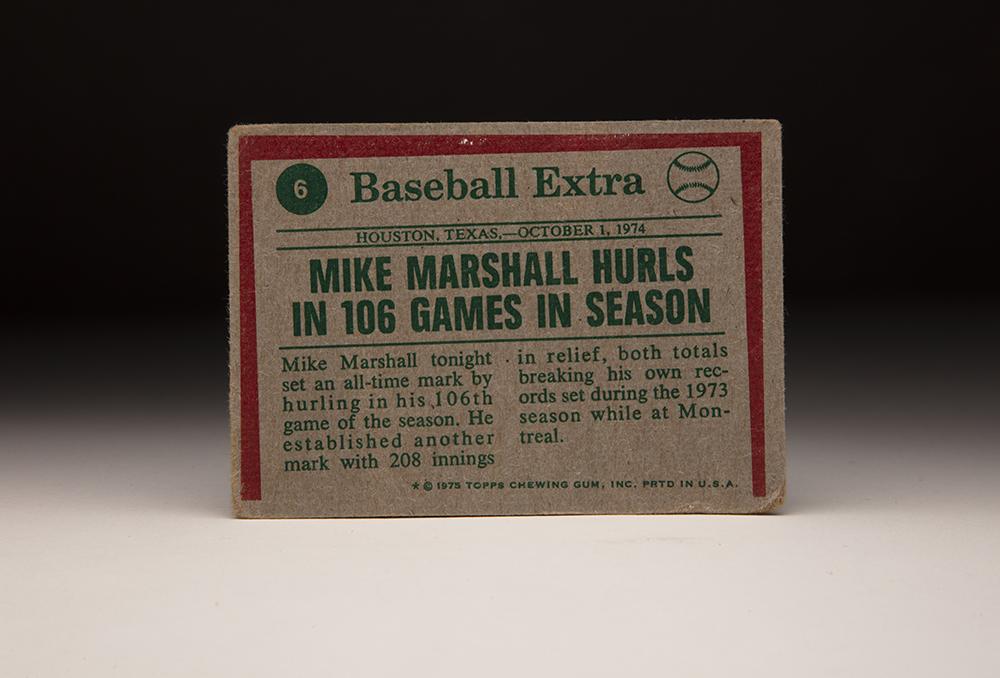

- #CardCorner: 1975 Topps Mike Marshall

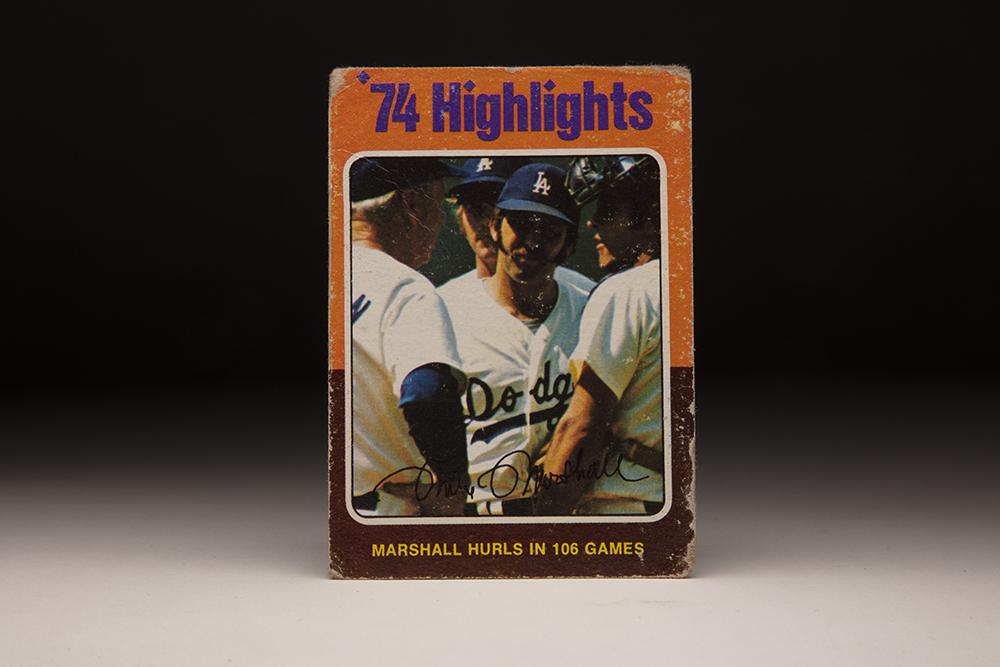

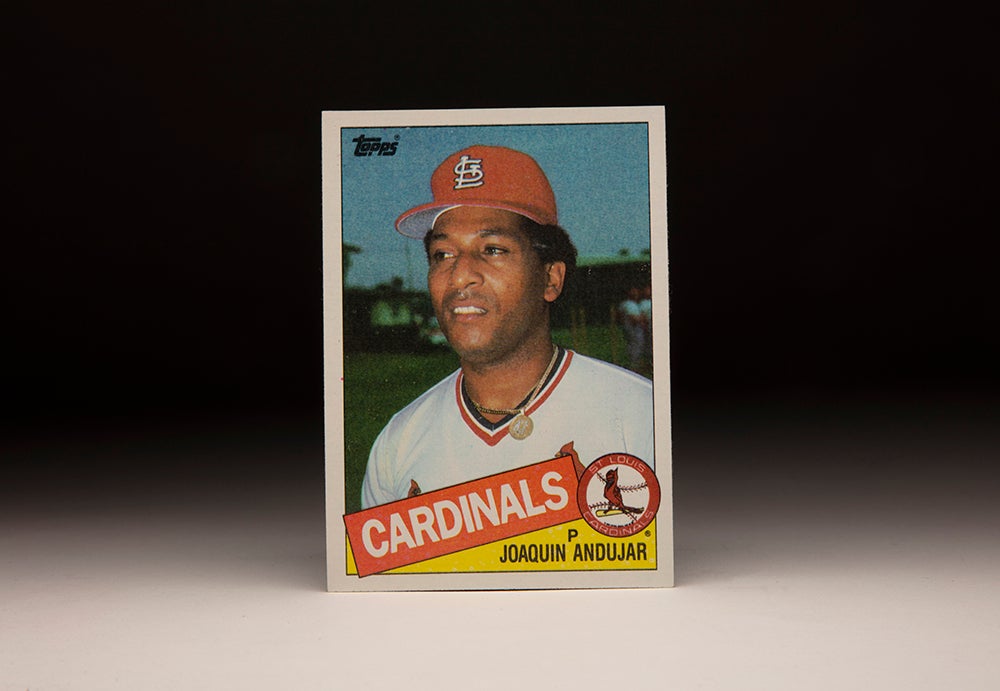

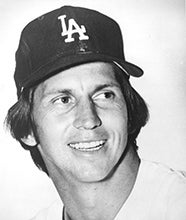

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Mike Marshall

The question of “most unbreakable baseball record” usually involves a discussion of Joe DiMaggio’s hitting streak, Cy Young’s victory total or Cal Ripken’s games-played mark.

But it is difficult to imagine any pitcher ever appearing in 107 games in one season. And that’s what would have to happen to knock Mike Marshall off the top of his list.

Born Jan. 15, 1943, in Adrian, Mich., Marshall took a unique path to a big league career that has almost no parallel. He signed with the Phillies on Sept. 13, 1960, as an infielder, entering the pro baseball ranks with little experience on the mound.

“I didn’t ruin my arm because back home there’s a bank teller who did,” Marshall told the Los Angeles Times in 1975. “I played in the field and he pitched all the time. He played in high school and college and went into pro ball and did pretty well until the bone chips caught up to him.”

Marshall began a steady climb through the Philadelphia system as a shortstop, hitting. 264 with 82 runs scored in 118 games for Class D Dothan of the Alabama-Florida League as an 18-year-old in 1961. He moved up to Class C Bakersfield in 1962 and then to Class A Magic Valley of the Pioneer League a year later, hitting .304 that season with 14 homers and 76 RBI.

In his first three seasons, Marshall never posted an on-base percentage less than .386 thanks to a keen eye at the plate that saw him averaging 85 walks per season. But a balky back had Marshall considering a career on the mound – something about which the Phillies had little interest.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

After hitting .275 four Double-A Chattanooga in 1964, Marshall – who was already attending Michigan State University in pursuit of what would eventually become a Ph.D. in kinesiology – began exploring the possibility of switching to the mound. The Phillies sent him to Class A Eugene of the Northwest League in 1965, where he hit .317 in 54 games while also going 6-5 with a 3.51 ERA on the mound. He also pulled double duty at Chattanooga that year before the Phillies sold his contract to the Tigers on April 11, 1966.

“I didn’t really start pitching until I was 21 and I didn’t throw a screwball until I was 24,” Marshall said. “When I did start to train appropriately, I had no injuries from youth programs.”

Marshall continued to pitch and play the field in 1966 with Double-A Montgomery, hitting .279 in 79 games while going 11-7 with a 2.33 ERA in 51 appearances – all out of the bullpen – on the mound. Then in 1967, Marshall transitioned exclusively to the mound, where he allowed just one earned run over 10 appearances with Triple-A Toledo before being called up to Detroit – where he made his big league debut on May 31 against the Indians.

Marshall demonstrated the arm that earned him the nickname “Iron Mike” for much of the rest of the year, becoming a stalwart in the Tigers bullpen as Detroit found itself in one of the great pennant races in baseball history. Marshall appeared in 37 games, going 1-3 with 10 saves and a 1.98 ERA. But in the final game of the season against the Angels – with the Tigers needing a win to force a one-game playoff against the Red Sox – Marshall was unable to squash a fourth-inning rally that turned a 4-3 California lead into a 7-3 advantage. The Angels won the game 8-5 to knock the Tigers out of contention.

The key play came when Angels pitcher Jim McGlothlin tapped a ball to shortstop that went for an infield hit.

“What a lousy way to lose,” Tigers catcher Bill Freehan told the Associated Press about McGlothlin’s single off Marshall. “It should have never been a hit.”

Marshall’s fine performance during his rookie season did not earn him a spot on the 1968 Tigers – a team that went on to win the World Series title. Marshall spent the entire season with Toledo, where he was 15-9 with 2.94 ERA as a starter. The Tigers then left Marshall unprotected following the season – and the Seattle Pilots grabbed him in the Expansion Draft.

By this time, Marshall had started throwing a screwball as a way to get left-handed hitters out. But most coaches advised against a pitch they saw as an arm-ruiner. Marshall appeared in 20 games for Seattle in 1969, mostly as a starter, before the Pilots returned him to Toledo to finish the season after he went 3-10 with a 5.13 ERA in 20 games. He made national headlines in late May – not for his pitching but because he received a black eye after being accosted by a gang outside his hotel in Cleveland. The assault also left him with two dislocated shoulders.

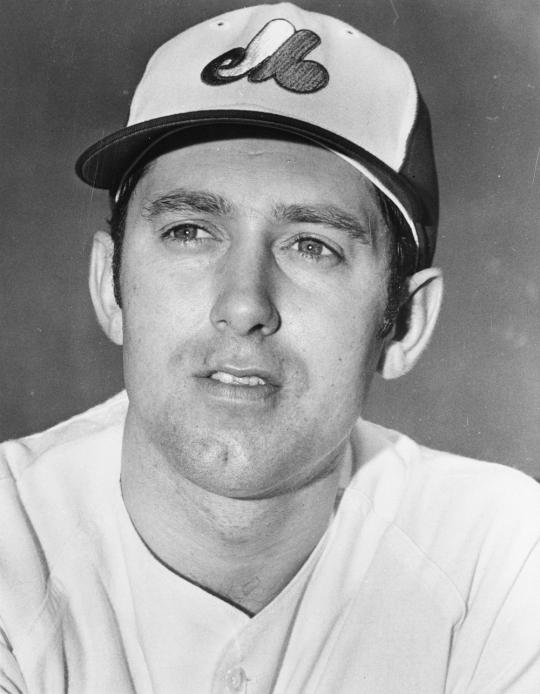

The Pilots sold his contract to the Astros on Nov. 21, 1969, and after pitching in just four games for Houston in June of 1970 he was traded to the Expos on June 23, 1970, in exchange for outfielder Don Bosch.

“It was only in the middle of the winter (of 1969-70) that my shoulder stopped aching,” Marshall told the Montreal Star. “My shoulders were so stiff and tight that I couldn’t even lift my arm.”

But after pitching effectively for the Winnipeg Whips of the International League following the trade the Montreal, the Expos recalled Marshall and manager Gene Mauch soon moved him to the bullpen. He made 14 appearances from Sept. 1-Oct. 1, working both ends of a doubleheader twice and finishing the year with a 3-7 record, three saves and a 3.48 ERA over 24 games for Montreal.

With his screwball becoming a reliable out pitch, Marshall was primed for success.

“I like to throw a hard breaking pitch, but sometimes it doesn’t like to be thrown,” Marshall told the Montreal Star. “My fastball is a matter of conjecture. Let’s just say that I also use a pitch that doesn’t break in either direction, and I affectionately label it a fastball.”

Mauch installed Marshall as the Expos’ closer in 1971 and he did not allow a run until May 10. A rocky June inflated Marshall’s ERA to over 6.00 but Mauch continued to show confidence in him – and Marshall completed the season with a 5-8 record and 23 saves over 66 games, including an NL-best 52 games finished.

By this time, Marshall – who was continuing his studies – was telling anyone who would listen that he was capable of pitching every day.

“If there’s a secret to pitching a lot, it’s training,” Marshall told the Philadelphia Daily News. “So little is known about training in baseball, it’s really a shame.”

In 1972, Marshall appeared in 65 games but was more effective than the year before, going 14-8 with 18 saves and a 1.78 ERA for a team that won just 70 times on the season. He finished fourth in the NL Cy Young Award voting and 10th in the NL MVP race.

Then in 1973, Mauch and Marshall set out to truly test the pitcher’s theories on durability. Marshall appeared in an MLB-record 92 games, going 14-11 with 31 saves and a 2.66 ERA over 179 innings. This time, Marshall finished second in the Cy Young Award voting – receiving just one fewer first-place vote than winner Tom Seaver – and fifth in the MVP race.

“My arm is never sore, never tired,” Marshall told the News of Paterson, N.J., prior to the 1974 season. “If you jog four miles a day and have a heart rate of less than 50, you can recover readily after pitching.”

But the Expos – perhaps thinking the overuse would catch up to Marshall – traded him to the Dodgers on Dec. 5, 1973, in a one-for-one swap for outfielder Willie Davis.

“I never had any problems with Gene Mauch. Not a single one,” Marshall told the Philadelphia Daily News. “His idea of how the game should be played and pitched was in exact agreement with mine. Our philosophies on the way to pitch were identical.”

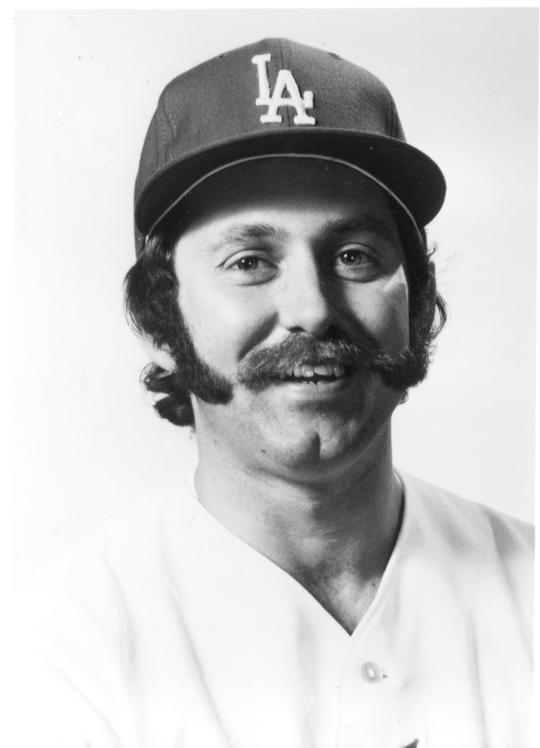

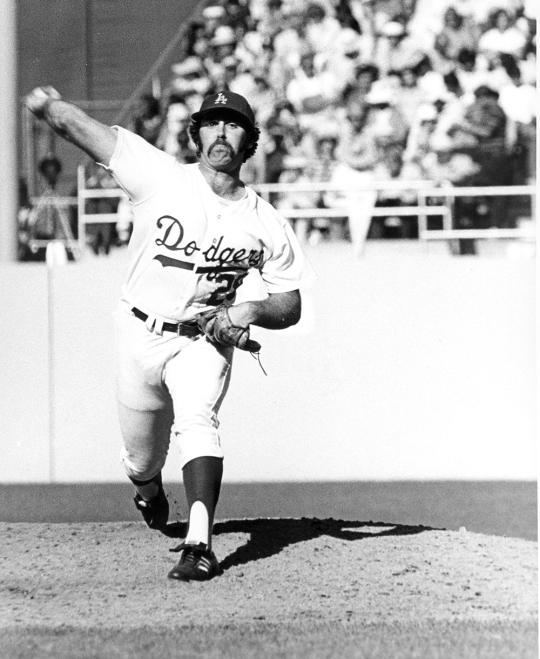

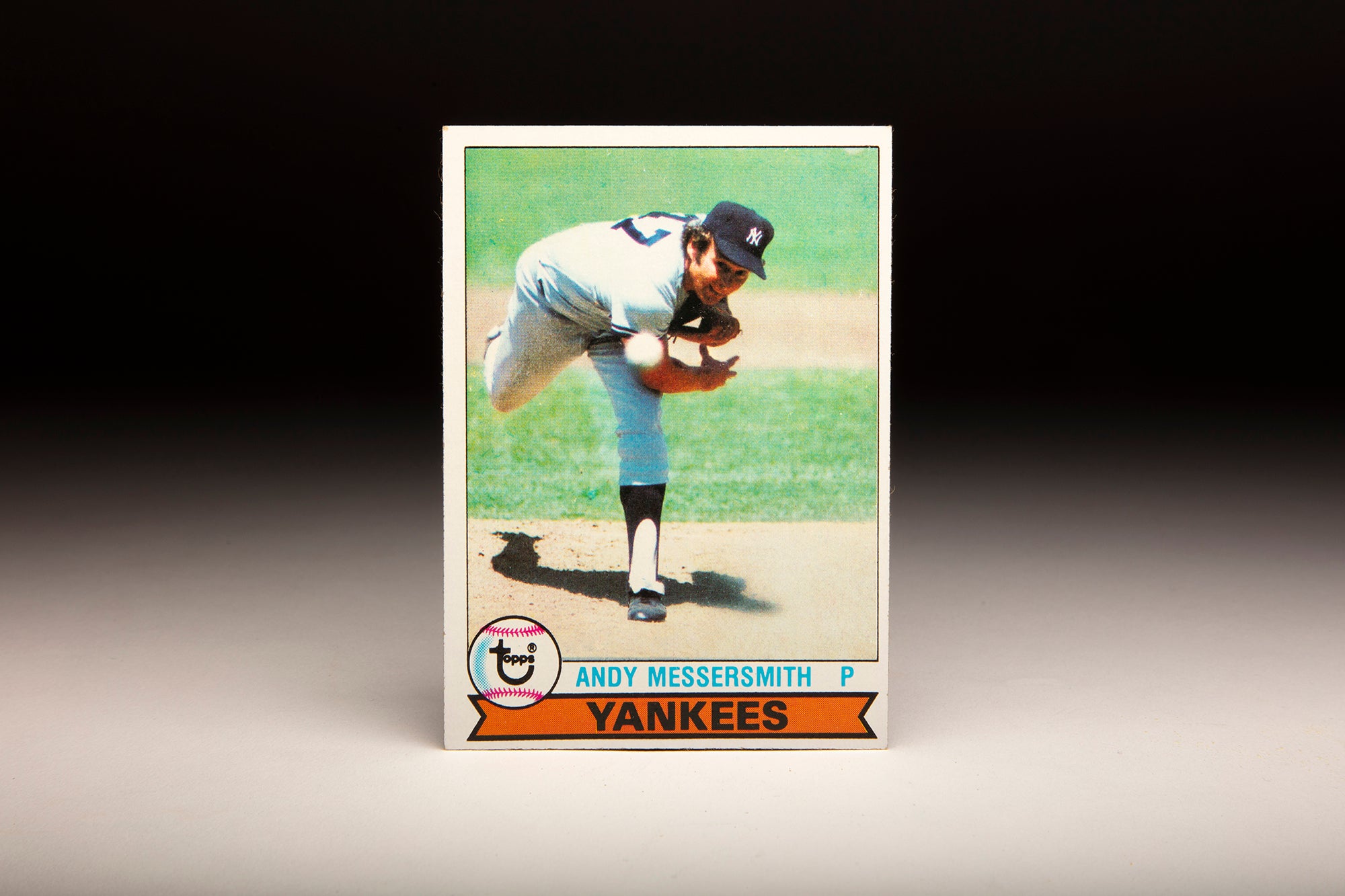

Marshall joined a Dodgers team that had brought several young stars through its farm system over about half a decade. It all came together in 1974 as Steve Garvey won the NL MVP Award, Don Sutton and Andy Messersmith anchored the rotation and Marshall closed games out as virtually a one-man bullpen. He had pitched in 33 games by the end of May, appeared a record 13 straight contests from June 18 through July 3 and wound up with a 15-12 record, 21 saves and a 2.42 ERA over an incredible 208.1 innings spread across those 106 games. Counting the postseason and his appearance in the All-Star Game, Marshall worked in 114 contests.

“My arm feels good,” Marshall told the Newspaper Enterprise Association during the 1974 season. “And I feel good. And as long as that’s the case, I can pitch every day.”

In his first postseason appearances, Marshall worked three scoreless innings over two games in the NLCS vs. the Pirates, allowing no baserunners. In the World Series, Marshall worked in every game against Oakland – earning a save in Game 2 while famously picking pinch runner extraordinaire Herb Washington off first base in the ninth inning. In total, Marshall posted six scoreless frames through Game 4.

In Game 5 – with the Dodgers trailing the series 3-games-to-1 – Marshall entered the game with the score tied at 2 and pitched a perfect sixth inning. But in the seventh, Joe Rudi led off with a home run after the game was delayed for six minutes when fans threw debris on the field. Marshall did not soft toss during the delay.

“I hit an inside fastball which, believe it or not, I sort of expected,” Rudi told the Associated Press.

For Marshall, it was a moment that did nothing to improve his relationship with his teammates.

“I’m a better student of hitters since Mike joined us this year,” Messersmith told the New York Times News Service. “But I don’t want to say things about him. I don’t think it’s fair for me to say things that he might not agree with.”

Marshall’s arm showed no signs of wear in 1975, but a rib cage injury limited his effectiveness as he went 9-14 with 13 saves and a 3.29 ERA in 58 games – earning his second and final All-Star Game selection. Then in the spring of 1976, Marshall made off-the-field news when he sued Michigan State University when – Marshall claimed – the school reneged on a promise to let him use their training facilities whenever he wanted.

Marshall also kept promoting his theories on pitching.

“I got 10 to 15 letters a week from youngsters requesting help for their sore arms,” Marshall told the Los Angeles Times in 1975. “I think there are epidemic proportions to this. What I think we have done over the past 20 years by using adult rules in children’s baseball programs is we have selectively taken the best arms and ruined them.”

But the combination of missed time due to the lawsuit and his outspoken views as the team’s player representatives led the Dodgers to trade Marshall to the Braves in exchange for Lee Lacy and Elias Sosa on June 23, 1976. A knee injury limited him to just five appearances in August – none after Aug. 28 – and he finished the year with a combined record of 6-4 with 14 saves and a 3.99 ERA in 54 games.

He reported to Spring Training late the following year due to his ongoing legal issues with Michigan State, publicly feuded with Braves manager Dave Bristol and was sold to the Rangers on April 30. Texas tried him as a starter but Marshall continued to miss time due to the Michigan State issue, frustrating Rangers’ management.

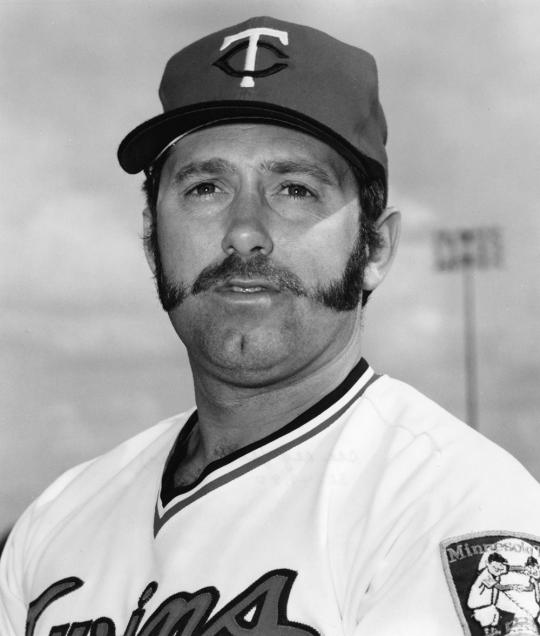

But after flirting with retirement, Marshall returned in May of 1978. His achy back, with had bothered him for decades, was improving following surgery and Marshall auditioned for the Twins – now skippered by Marshall favorite Gene Mauch. After Rod Carew openly questioned why Twins owner Calvin Griffith would not sign Marshall, the Twins bought the 35-year-old Marshall into the fold on May 15, 1978.

“It’s obvious Mike is now having fun playing baseball,” Mauch told the Orlando Sentinel. “And he’s never pitched better. At Montreal, he never could un-grit his teeth.”

Marshall finished the 1978 season with a 10-12 record, 21 saves and a 2.45 ERA over 54 games. Then in 1979, Marshall recaptured the magic of the early 1970s by appearing in 90 games – still the AL record – while going 10-15 with an AL-best 32 saves and a 2.65 ERA over 142.2 innings. His 84 games finished broke his own record of 83 set in 1974 – another mark that may never again be approached.

Following up on his seventh-place finish in the AL Cy Young Award voting in 1978, Marshall finished fifth in 1979 and also placed 11th in the AL MVP vote.

But the good times would not last. In 1980, the threat of a work stoppage loomed for most the season – and Marshall, as the American League player representative, was on the front lines in the clubhouse and in the media. This strained his relationship with Mauch, who began using Marshall in mop-up roles. The Twins lost 10 of the 11 games Marshall pitched in May, and on June 6 Marshall was released – with the Twins still on the hook for most of the three-year, $850,000 deal Marshall signed in January of 1979.

“(My mother) said: ‘If you’re so smart why can’t you get along with people?’” Marshall said. “I wish I knew.”

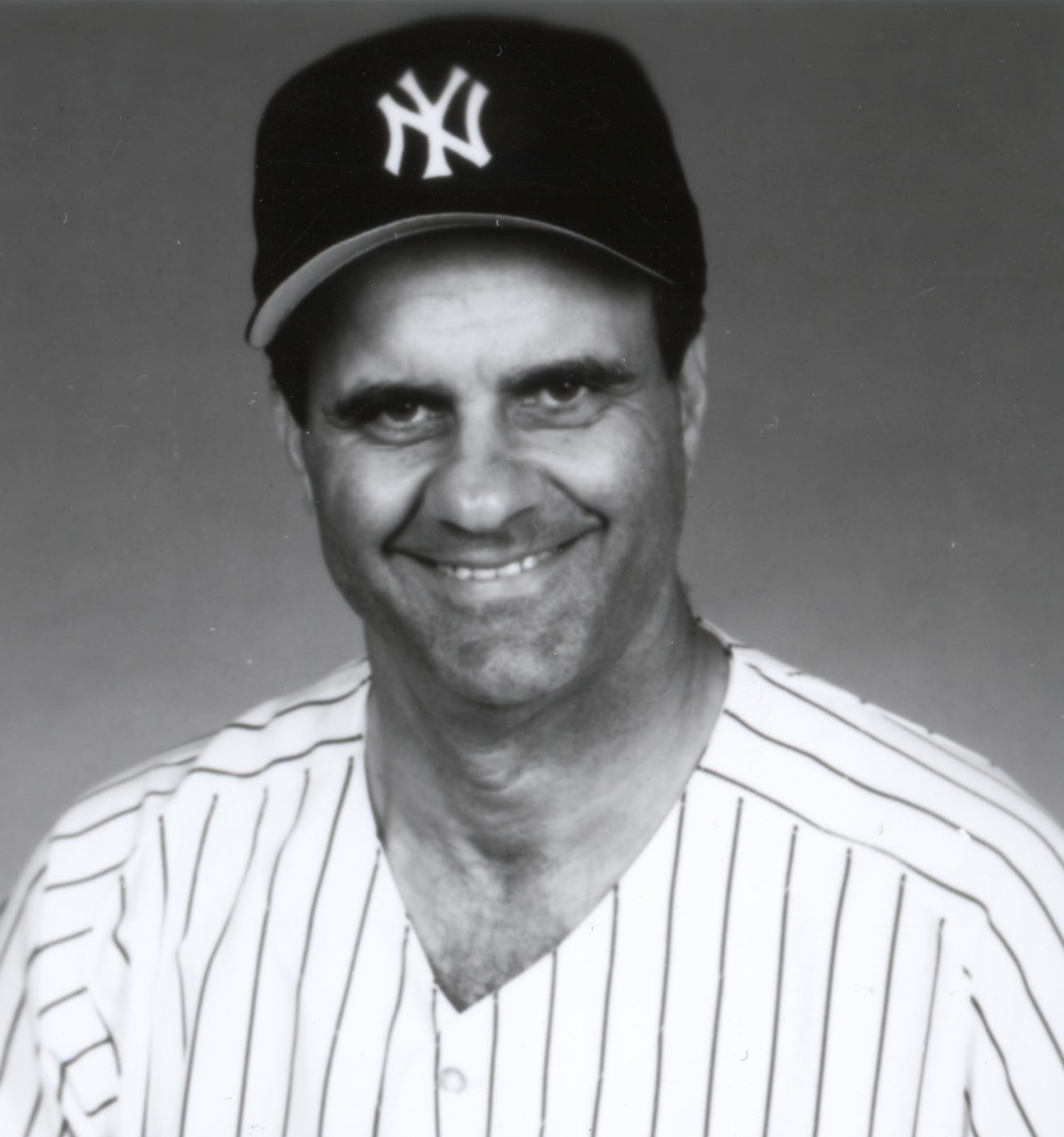

After finding no suitable offers the rest of the 1980 season, Marshall got a look from the Expos in Spring Training of 1981 but no contract was forthcoming. Then, after the 1981 strike was settled, Marshall signed with the Mets – skippered by union stalwart Joe Torre – on Aug. 19.

“Marshall takes the mental strain off (closer Neil) Allen,” Torre told the Minneapolis Star Tribune. “From a mental aspect he can help this club.”

Marshall went 3-2 with a 2.61 ERA over 20 games with the Mets but did not record a save.

“It’s exhilarating. I’ve always enjoyed pitching,” Marshall told the Star Tribune late in the 1981 season when he was with the Mets. “It’s selfish. I enjoy it. There’s no financial reason to do it. There’s no ego reason to do it. There’s no reason other than I just want to be here.

“I’m not treated with the disdain that (Gene) Mauch did last year. That means a lot.”

On Oct. 12, the Mets released Marshall. He continued to look for work and appeared in one game for the Angels’ Triple-A team in Edmonton in 1983 – but he never pitched in the big leagues again.

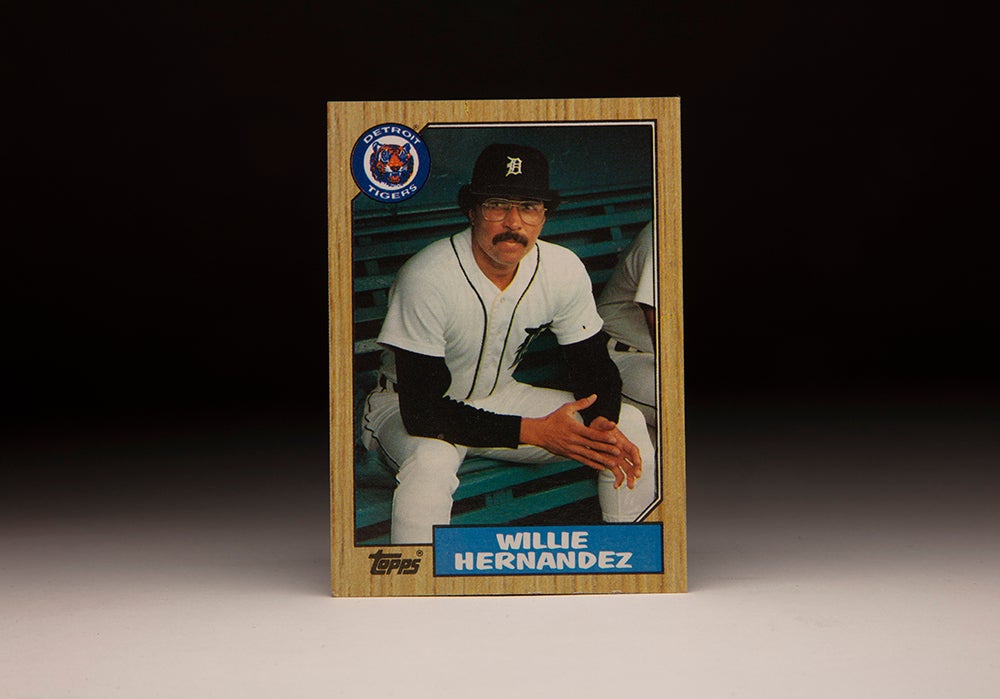

When he left the game, Marshall’s 188 saves ranked fifth on the all-time list. He posted a 97-112 record and 3.14 ERA over 14 seasons. Only Marshall and Kent Tekulve have pitched in 90-or-more games in as many as three different big league campaigns.

And by any measure, Marshall did it by following his own unique playbook.

“You don’t do what I’ve done in life if you’re constantly worrying about those who are jealous of you,” Marshall told the Star Tribune in the final season of his career. “That’s something my mother taught me as a kid. If someone’s picking on you they’re probably jealous of you. I don’t know if that’s true or not, but my mother’s word is right next to Freud’s.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum