- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1979 Topps Andy Messersmith

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Andy Messersmith

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

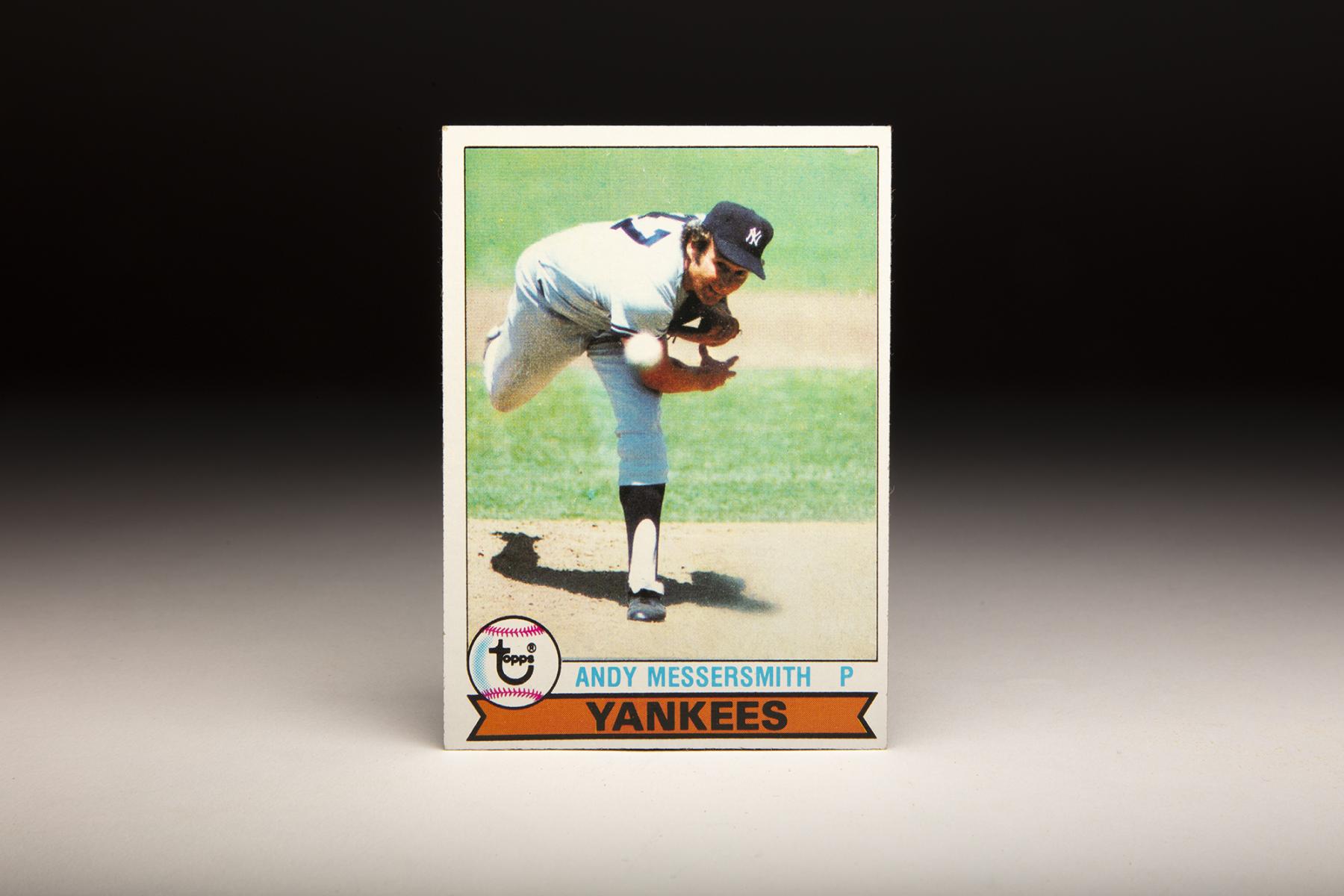

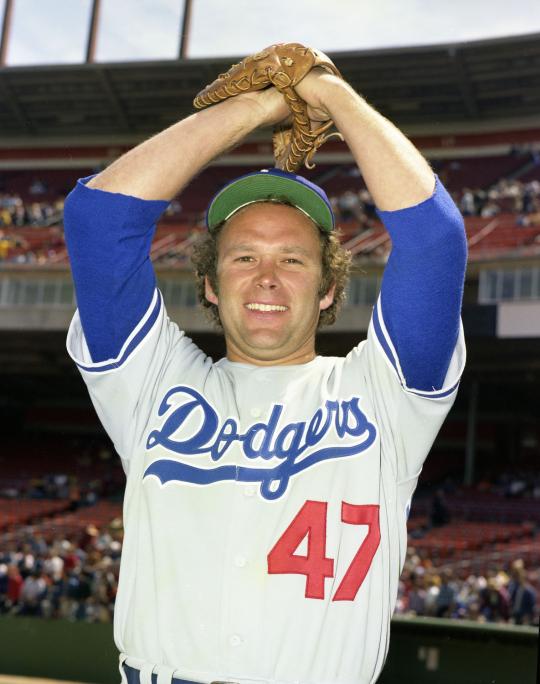

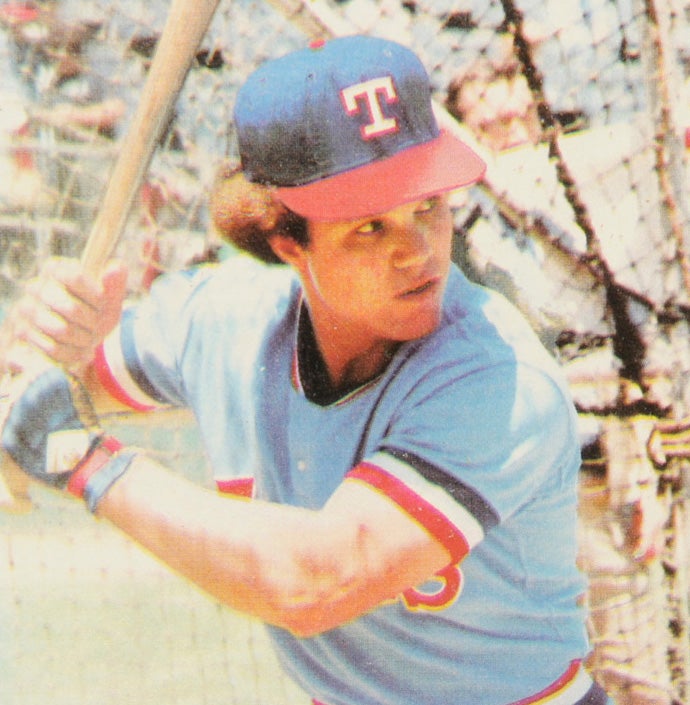

In photographing pitchers during the 1970s, Topps tended to show them from the side, or at least at a partial angle. Andy Messersmith’s 1979 Topps card is a little different, however. It is taken almost head-on, as if we were watching from the viewpoint of the hitter (or the catcher or the umpire). This gives us a small sense of what it must look like for a batter as he eyes the pitcher.

In the case of Messersmith, we notice that his left leg is firmly planted and that his right leg, bent at the knee, is completely off the ground. As an added bonus, the card gives us a peak at the baseball itself, which has just been released from Messersmith’s right hand, and is now juxtaposed against his right arm.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Hitters often talk about how they can pick up the seams and the spin of the ball, allowing them to distinguish whether a fastball or a breaking ball is being thrown. In this case, the ball is too blurry to give us any idea of what is happening with the seams and the spin. Given my own poor eyesight, I would imagine that every pitch would appear blurry to me, providing me with no clue as to whether a fastball, curve, slider or change-up was headed my way.

Even though this is a still shot of Messersmith, it gives us a taste of just how challenging it must be to stand in against a live major league pitcher. Sure, hitters are taught to keep their concentration on the ball, but there are so many distractions: One of the pitcher’s legs is bent, the other is firm, his head is tilted to the side, and there are shadows developing on the mound itself. All the while, the hitter has to pick out the ball against a background of a gray or white shirt, making the task at hand that much tougher.

It’s a wonder that anyone can get a hit in the face of these obstacles, and yet, major league hitters do it time and time again.

At first glance, Messersmith’s mechanics look pretty sound here on what turned out to be his final Topps card, but in retrospect, we know that his arm was anything but sound during the late 1970s. It wasn’t often that Messersmith had the chance to actually appear in game action for the New York Yankees; in spending one season with the team, he was healthy enough to make only five starts and one relief appearance during the 1978 season. The rest of the time he spent on the disabled list.

Given his lack of pitching in 1978, it’s relatively easy to figure out in what game this photograph was taken. Messersmith is wearing the Yankees’ road grays, so it has to be an away game. He made only two appearances on the road that season, one in Cleveland and one in Oakland. The game in Cleveland was a night game, so we can rule that one out. The game in Oakland was an afternoon start, so that must be the game. It occurred on June 3 at the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum.

Messersmith started the game that afternoon. He pitched five innings, allowing five runs (four earned), including three home runs. Relieved by Ken Clay, Messersmith took a 5-1 loss, one of three defeats he suffered during the season. They were only his decisions as a Yankee; he never won a game for the franchise.

In fact, Messersmith would not even have a chance to pitch for the Yankees in 1979, the year that this Topps card came out. That’s because the Yankees chose to release him in November of ‘78. Instead, Messersmith signed on with one of his early teams, the Los Angeles Dodgers, where he made only 11 appearances before realizing that the end of the line had come. For a once-dominant pitcher who had appeared in All-Star games and contended for the Cy Young Award on multiple occasions, it was an ungracious way to end a fine career.

Messersmith’s professional career began in California, but it could just as easily have started in Detroit. In 1965, the Tigers took him in the third round of the newly formed amateur draft, but could not convince the young right-hander to sign. Messersmith went back to college college – he pitched for the University of California at Berkeley – and then declared himself eligible for the draft in 1966. This time he was taken on the first round, with the Angels taking him 12th overall. Of the 11 players taken ahead of him, only four would make the major leagues, with Duffy Dyer having the biggest impact as a longtime backup catcher.

Although Messersmith was only 20 at the time, the Angels believed that he was advanced enough in his pitching skill to merit an assignment to Triple-A Seattle of the Pacific Coast League. After all, Messersmith already possessed three different pitches in his arsenal: A fastball, curve ball, and change-up. He appeared in 18 games, won four of 10 decisions, and put up a respectable ERA of 3.60. Messersmith seemed to hold his own at Triple-A, but the Angels felt that he needed to move down a level in 1967. So they reassigned him to Double-A El Paso, where his ERA actually rose to 4.34.

On the surface, Messersmith’s numbers were mediocre, but the Angels felt he was ready to move back up to Triple-A in 1968. In 20 games, he posted an ERA of under 3.00, which was outstanding for a hitters’ league like the PCL. By July, the Angels felt he was ready. Angels manager Bill Rigney expressed optimism about Messersmith, and with good reason.

“This fellow has the potential to be the very best pitcher in the league,” the Angels’ skipper told John Weibusch, corresponding for the Sporting News.

Rigney broke Messersmith in slowly, giving him only five starts and using him mostly in middle relief. He responded well, striking out 74 batters in 81 innings while recording an ERA of 2.21. In 1969, Rigney moved his young prodigy into the starting rotation on a fulltime basis. With a repertoire featuring a terrific curve ball, a deceptive change-up and a plus fastball, Messersmith dominated the competition.

Making 33 starts, he struck out 211 batters and won 16 games, essentially becoming the ace of the Angels’ staff. Though the Angels did not contend in the newly formed American League Western Division, Messersmith did receive some support in the league’s MVP voting.

The 1970 season would not turn out as well, but not because American League batters had caught up to Messersmith. Rather, it was a matter of injuries. First, the right-hander hurt his shoulder while sliding into a base. He also struggled with pain in his ribcage. Making only 26 starts, he managed to win 11 games, but his ERA rose by nearly a run.

A breakout season awaited Messersmith in 1971. His health restored, he made 38 starts, logged 276 innings and won 20 games. He also lowered his ERA to just below 3.00. Not only did Messersmith make the All-Star team, but he also finished fifth in the Cy Young Award balloting.

The Angels expected more greatness from Messersmith in 1972, but health would not allow it. An injury to one of his pitching fingers resulted in surgery, limiting his effectiveness that summer. Even at less than 100 percent, Messersmith forged an ERA of 2.81, but a lack of run support from Angels batters resulted in a record of 8-11.

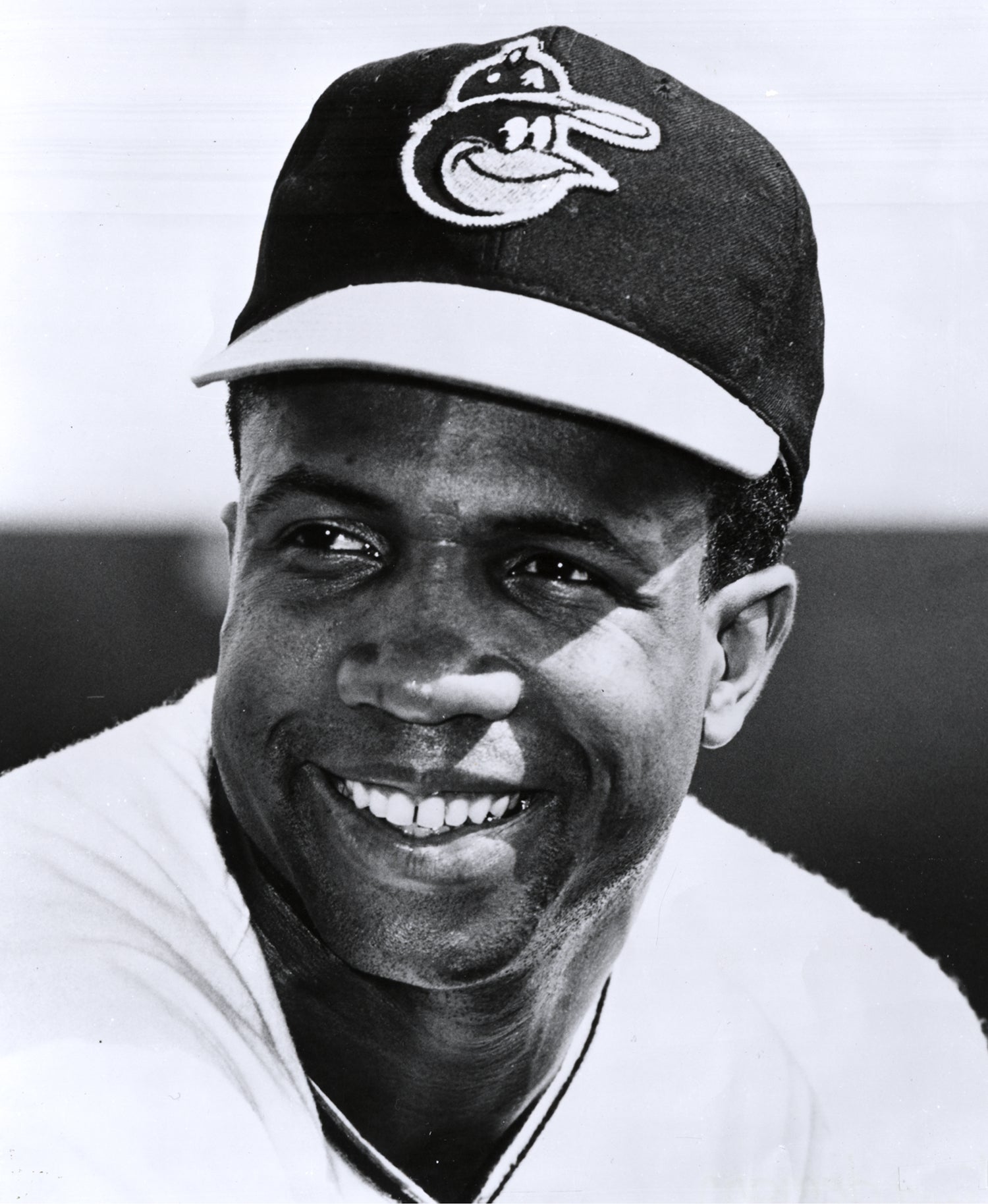

That would turn out to be Messersmith final season with the Angels. In January of 1973, he heard the stunning news that he had been traded – to the crosstown Dodgers. It was a trade of epic proportions, sending Messersmith and veteran third baseman Ken McMullen to Chavez Ravine for a package of five players, including Hall of Fame outfielder Frank Robinson.

Healthy again in 1973, Messersmith found a welcome backdrop in Dodger Stadium, known for being friendly to pitchers. He pitched 249 innings, lowered his ERA to 2.70 and won 14 games for the second-place Dodgers.

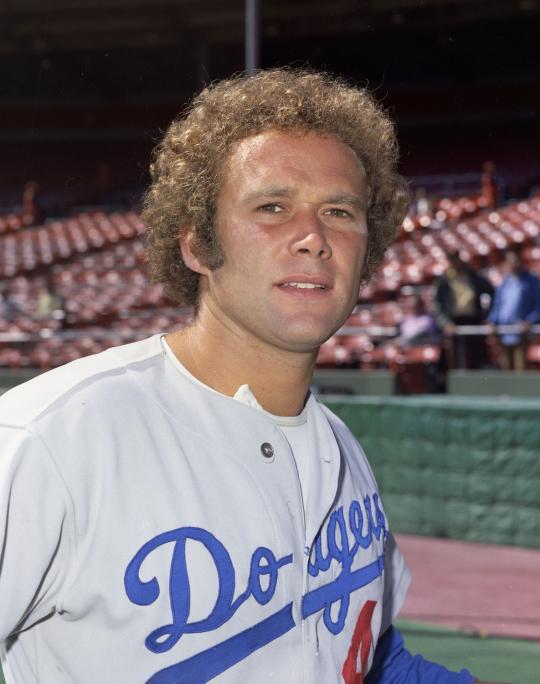

Messersmith’s second season in Dodger Blue would turn out to be the best of his career, at least to that point. He emerged as the ace of a talented Dodgers staff that already featured Don Sutton and Claude Osteen. Messersmith won 20 games, posted an ERA of 2.59 and struck out 221 batters. Those numbers produced a runner-up finish in the NL Cy Young Award voting, while helping the Dodgers to their first postseason berth since the 1966.

In the NLCS, he continued his brilliance by putting up a dominant start against the hard-hitting Pittsburgh Pirates. Unfortunately, the season ended on a down note; Messersmith was roughed up in two losing starts against Oakland, as the Dodgers lost the World Series in five games.

On the whole, Messersmith had enjoyed a banner season. He made the All-Star team, won a Gold Glove Award and finished 16th in the MVP Award balloting. In response, the Dodgers offered him a raise, from $100,000 to $115,000. Messersmith was willing to accept the raise, but he also wanted a no-trade clause included in his contract. The Dodgers refused, so Messersmith decided to pitch the entire 1975 season without actually signing his contract.

Somehow, Messersmith turned his performance up another notch in 1975. Lowering his ERA to 2.29, he won 19 games and led the National League in starts, complete games, shutout, and innings pitched (321). It was a phenomenal season, one that was somewhat overshadowed by the Dodgers’ failure to repeat as NL West champions.

As the 1975 season wound down, Messersmith and the Dodgers reached an impasse on contract talks. He decided to file a grievance with the Players Association, citing baseball’s reserve clause, which allowed teams to annually renew a player’s contract of they so desired. In response, the Dodgers offered Messersmith a three-year contract worth more than $400,000, but he turned down the offer.

“I’ve come this far,” Messersmith explained to famed sportswriter Jerome Holtzman. “I need to see it through. There’s no reason why a club should be entitled to renew a player’s contract year after year if the player refuses to sign and wants to go elsewhere.”

A quiet and reserved man, Messersmith did not want the public spotlight, but he felt that taking a stance against the reserve clause was the right thing to do. Another pitcher, veteran left-hander Dave McNally, was also in the middle of a contract dispute with the Montreal Expos and decided to join Messersmith in filing a grievance.

In the late stages of November, the case went before an arbitration board featuring one representative from the players, another from management and an independent arbitrator named Peter Seitz. A few weeks later – with the players and management representatives unsurprisingly voting for their side – Seitz announced his ruling, one that favored Messersmith and McNally. He agreed with the players’ contention that teams could only renew an unsigned contract for one season; after that, a player would become a free agent.

The ruling not only made Messersmith free to sign a contract with any team, but it also forced the owners to negotiate a new Collective Bargaining Agreement, one that would allow players to become free agents after completing six years of service time.

To the surprise of Messersmith, few teams showed interest in him. In fact, no teams made him an offer during the winter months. It was not until Spring Training that three teams – the Yankees, the Angels and San Diego Padres – made formal offers. When Messersmith turned down the Padres’ proposal of four years and $1.15 million, team owner Ray Kroc angrily told the Associated Press, “He can work in a car wash.”

Instead, Messersmith continued to wait for a better deal. That offer came shortly after the start of the season, when Atlanta Braves owner Ted Turner gave him a three-year contract worth roughly $1 million, complete with a no-trade clause.

“We just felt Andy Messersmith was too good to work in a car wash,” Turner gleefully told the AP.

Messersmith also became a symbol of Turner’s offbeat style. The owner encouraged his players to wear their nicknames on the backs on of their jerseys. For example, Jimmy Wynn wore “Cannon,” short for “The Toy Cannon.” Messersmith, at the urging of Turner, put the word “Channel” on the back of his jersey. Channel was not Messersmith nickname; it was actually “Bluto.” So why Channel? When paired with Messersmith’s No. 17, the back of the jersey read “Channel 17,” which just so happened to be the local station in Atlanta that carried Braves games – and was the future TBS Superstation. This was a perfect way to promote Turner’s flagship station.

With the late start to his season, and without the benefit of Spring Training, Messersmith’s pitching fell off in 1976. He was also bothered by a leg injury. He was still good, as evidenced by a 3.04 ERA and a selection to the All-Star team, but he wasn’t the dominant right-hander who had been seen in Southern California.

Even in a truncated season, Messersmith pitched over 200 innings. But by 1977, the heavy workload, dating back to his days in Los Angeles, began to take its toll. After a poor start to the season, Messersmith fell during a game in July, landing on his right elbow. A visit to the doctor detected bone chips, which may have been in the elbow already. The doctor recommended surgery, ending Messersmith’s season.

Messersmith would never again pitch for the Braves. That winter, the Braves sold his contract to the Yankees, who assumed all of the money owed the contract. It was a risky proposition, but it seemed to pay off in the early days of Spring Training. Messersmith pitched well, impressing his new manager, Billy Martin. But then, while trying to cover first base in an exhibition game, Messersmith had to reach back for an errant throw from the Yankee first baseman. Messersmith fell to the ground, separating his right shoulder.

The Yankees feared a season-ending injury, but Messersmith worked his way back diligently. Only 10 weeks after the shoulder injury, he returned to the mound. Clearly, he wasn’t ready. He made the five starts described earlier, struggled badly, and lost his spot in the rotation. That winter, the Yankees gave up on Messersmith, giving him his unconditional release.

Attempting a comeback with the Dodgers, Messersmith struggled before suffering inflammation of a nerve in his pitching arm. The condition mandated surgery, ending Messersmith’s season, along with his brief comeback in Los Angeles. Messersmith decided that it was time to retire.

Preferring a quiet life after baseball, Messersmith moved to a beach community located about an hour outside of San Francisco. For the better part of the next decade, he remained almost completely away from the game, until receiving an offer to coach a local team at nearby Cabrillo College. Messersmith served two stints at Cabrillo before retiring in 2007.

For the most part, Messersmith has remained out of the public spotlight since his major league career. As a man who cherishes his privacy, that’s the way that he prefers it. But back in the 1970s, few players had more of an impact than Andy Messersmith, first as a dominant pitcher and then as one of the trailblazers who decided to face the reserve clause head-on.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum