- Home

- Our Stories

- As the game changes, so has Spring Training

As the game changes, so has Spring Training

There are condominiums where the Ramada Inn once stood in Winter Haven, Fla. There are a couple of fast food restaurants, and a strip mall across the street where orange trees once stood back in 1974.

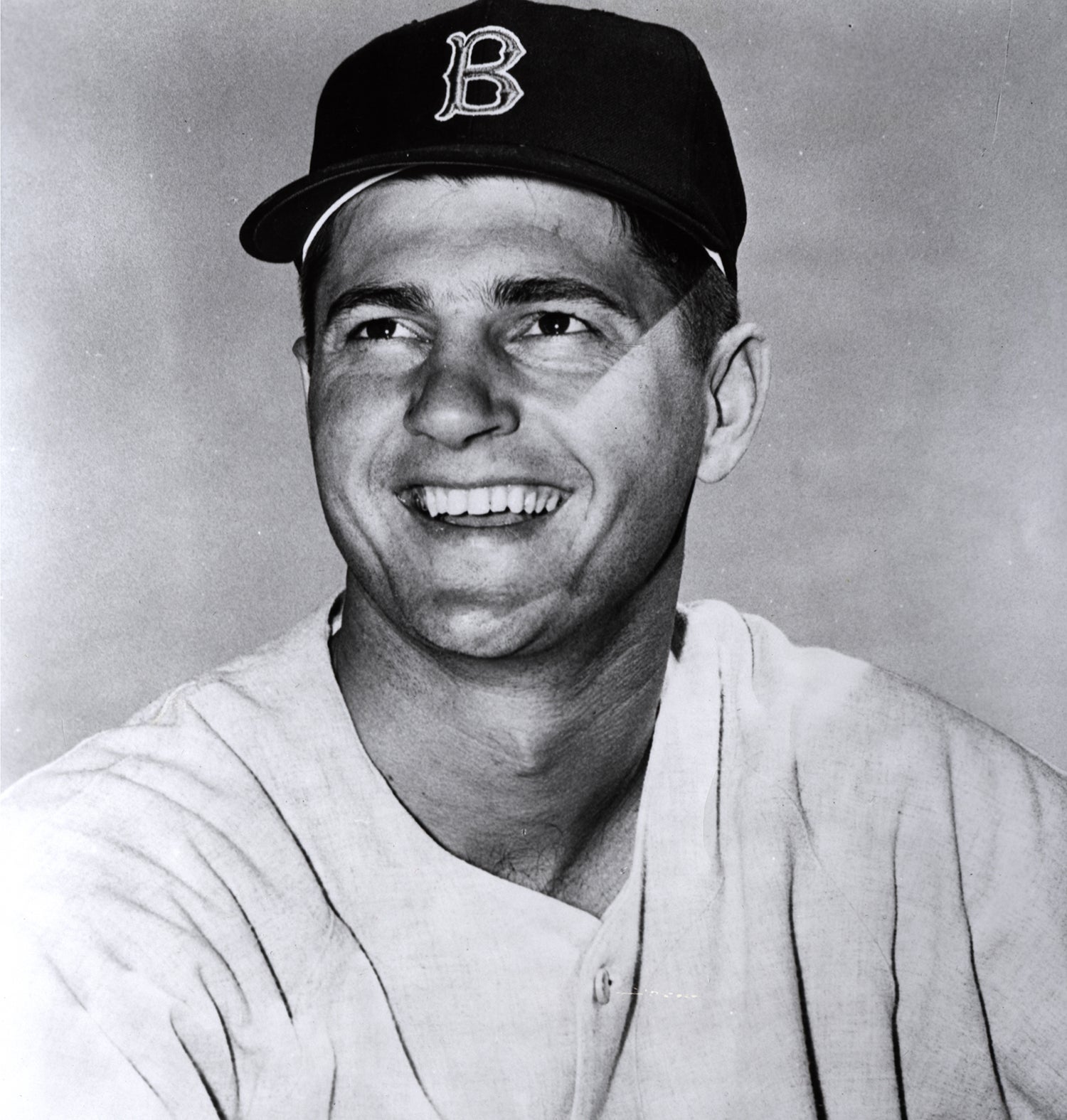

In the back of that Ramada Inn was a single tennis court, and in March 1974, there were a good three dozen fans watching an unusual match. On one doubles team was Ted Williams; on the other, Carl Yastrzemski.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

Ted was 55 that March, Yaz was 34 and very much an active member of the Red Sox. Some of the spectators were in the Red Sox organization at the time, some were in the media, some were just fans who heard about the game.

Ted didn’t move too well then. Yaz ran around every shot so that he could hit backhand, never changing his bottom hand (baseball bat) swing. When Ted missed a shot, there was the expected explicative shouted out, while Yaz would grimace and mumble and look down. They played for more than 70 minutes as if they were trying to be transported decades ahead in time to Roger Federer-Rafael Nadal at Wimbledon.

“Ted can’t take losing to Carl,” said one spectator, Red Sox vice president Haywood Sullivan. “And you know Carl wasn’t going to let Ted beat him, not at this point in his career. What makes them Hall of Famers is what makes this so much fun.”

Yastrzemski’s team eventually won. “Every (one) gets lucky sometime,” said Williams.

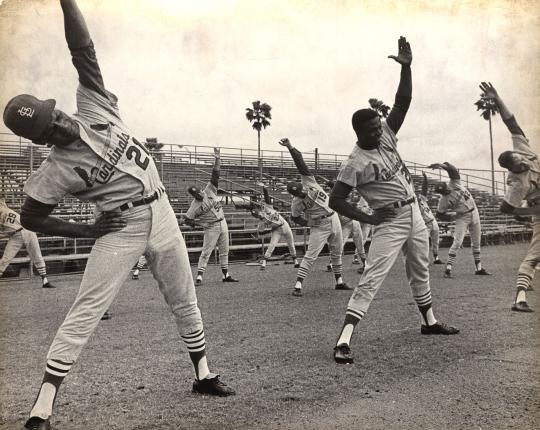

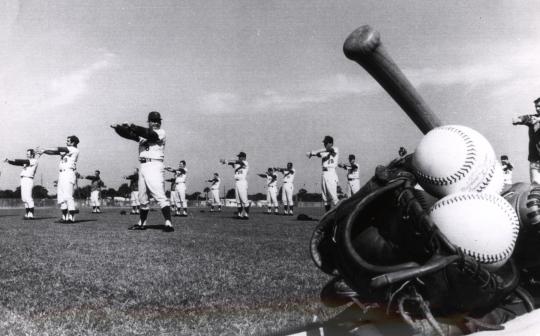

Spring Training was so simple back then, especially in a Tennessee Williams town like Winter Haven. They’d be lucky to get 1,000 fans at a game. Players went to barbecues at locals’ houses. When they practiced in the morning, players and fans mingled with one another.

The Grapefruit League dominated, as 17 of the 24 teams trained in Florida, and word of phenoms – from Walter Bonds for the ’64 Indians to Mike Anderson of the ’72 Phillies – spread by landline phones, or word of mouth. So would home runs you thought you’d never see, like one Bobby Darwin hit in Orlando for the Twins or another Mark Corey hit for the Orioles in Ft. Lauderdale.

Teams often had to bus to separate minor league fields for detail work, like the “back field” in Miami where Earl Weaver taught all his trick plays. Parking was never a problem; there was a designated spot at the Miami stadium for the newspaper Cuban Star, but Mike Cuellar thought it was for him and parked there every morning. Drills were simple, easy, and one time during batting practice Boston Globe scribe Clif Keane noted Mike Torrez as not moving from one spot for 42 minutes. Writers could hang out with players in the clubhouse during games.

Spring Training now is big business. Teams sell out their entire schedule by New Year’s Eve. Travel companies book Spring Training packages, with player appearances. Taxpayer dollars have paid for lavish 21st century complexes as Arizona has now gained 15 of the 30 major league teams, and places like Winter Haven, Vero Beach (“Dodgertown”) and Miami have long since given way to complexes with dozens of fields for major and minor league players.

Fans’ access to players is more limited now, the media gets but limited minutes in the morning and after games.

But Spring Training is the break from many a winter back North, a joyride for people who love baseball.

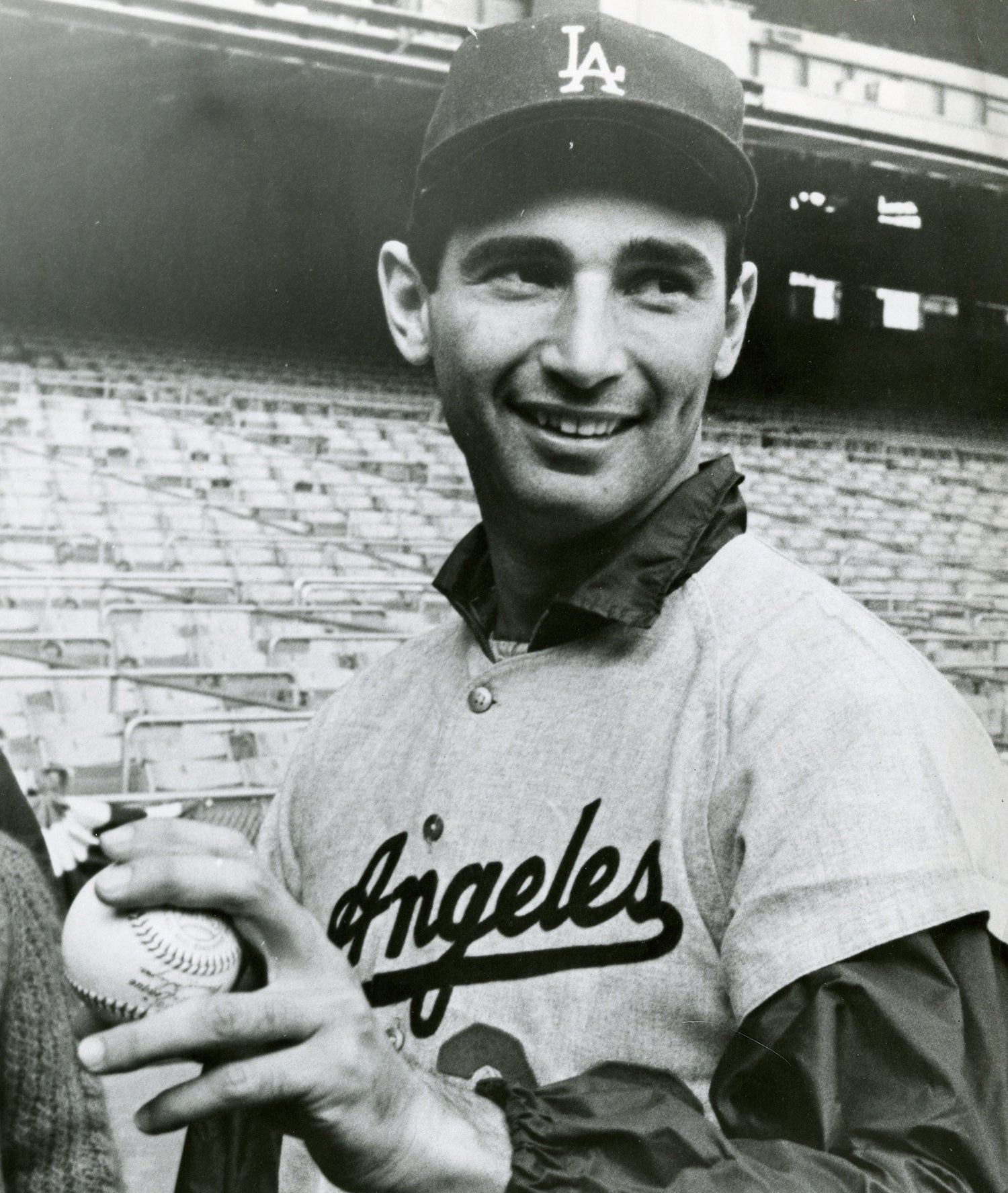

I remember a Yankees 10 a.m. “B” game in Lauderdale in which there were so few fans that I heard the “zzzzzzz” of Dave Righetti’s curveball. I remember watching a 50-something year old Sandy Koufax throwing BP in Dodgertown and being chilled.

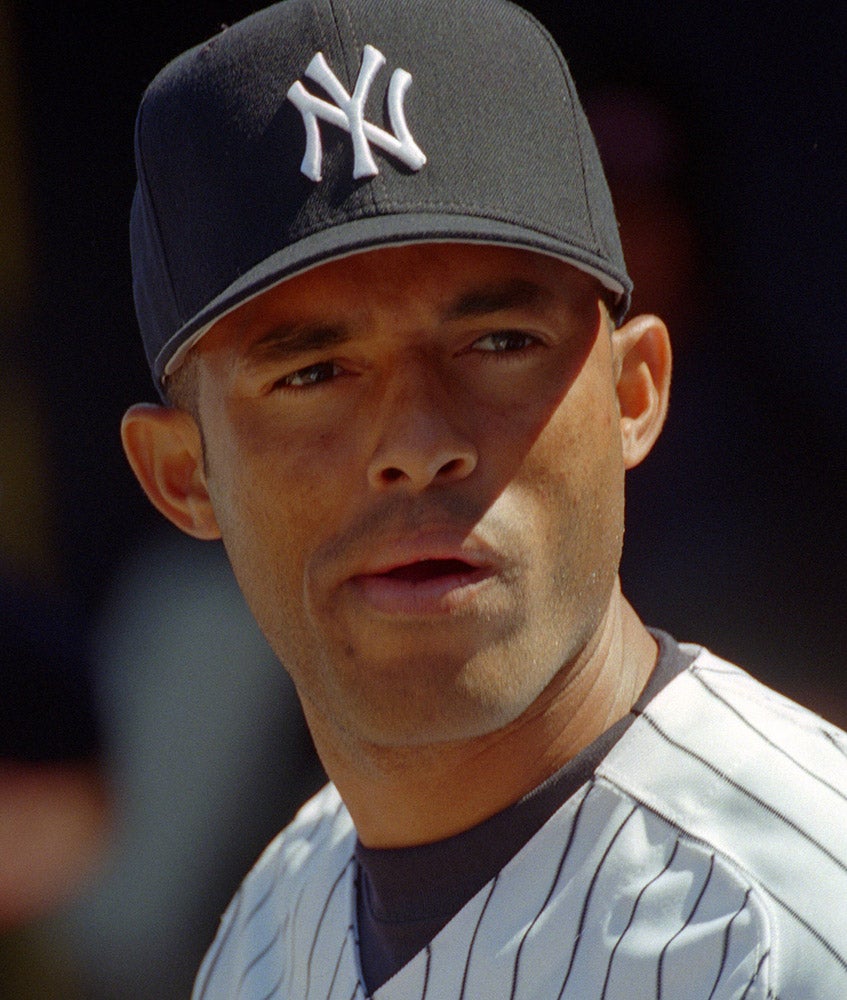

I remember being on the back field in Ft. Lauderdale watching pitchers’ fielding practice with manager Buck Showalter, marveling at a kid I thought should play shortstop.

“Remember the name,” Showalter told me. “It’s Rivera, Mariano Rivera.”

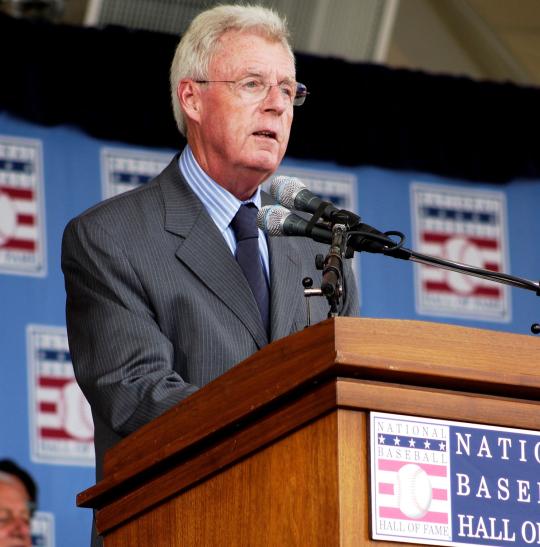

Peter Gammons won the Baseball Writers’ Association of America’s J.G. Taylor Spink Award in 2004