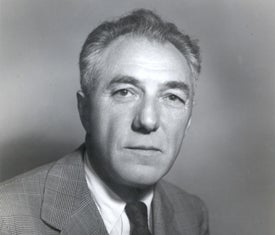

2019 Ford C. Frick Award winner Al Helfer

Al Helfer, who was big in stature, big in personality and a big league mainstay in broadcast booths across the country for four decades, is now among the winners of baseball broadcasting’s biggest award.

The burly 6-foot-4 Helfer, who worked behind a microphone in the majors for eight different clubs, was named the 2019 Ford C. Frick Award winner.

Helfer called games for the Pirates (1933-34), Reds (1935-36), Yankees (1937-38), Brooklyn Dodgers (1939-41, 1955-57), Yankees (1945), New York Giants (1945, 1949), Phillies (1958), Houston (1962) and Oakland (1968-69) – as well as gaining a national following with his Game of the Day chores in the early 1950s.

Following stints with the Reds, Yankees and Dodgers, he would serve in the Navy in World War II. Often aboard destroyers and destroyer-escorts in the North Atlantic, Mediterranean and Caribbean Theaters, and was wounded once before being discharged as a lieutenant commander.

“Other guys had it a lot worse,” Helfer said. “I won’t trade on it. I’m glad I did it, but I wouldn’t want to do it again.”

After WWII, Helfer gained his greatest prominence on the Mutual Broadcasting System’s Game of the Day broadcasts. For a five-year period between 1950 and ‘54, he was travelling to a different ballpark six days a week.

A rewarding but exhausting assignment, it was due to this Game of the Day exposure – the broadcasts carried by approximately 400 stations in non-MLB markets and around the world by the Armed Forces Radio Network – which Helfer became one of the nation’s best-known baseball broadcasters. It was said that his audience reached 80 million at times.

According to Helfer – who received his nickname “Mr. Radio Baseball” during these years – he was receiving fan letters from China, Nigeria, Korea, South Africa, Australia and even Moscow.

“You can’t beat this life if you like sports as much as I do. If this were not my business, it would be my hobby,” he told the Chicago Tribune in 1952. “But every job has a hook in it. Mine is travelling. I’ve been living out of a suitcase most of my working life.

“Fans repeatedly say they envy me. I see a ballgame every day and get paid for it. The broadcast is the whipped cream on my cake. What they don’t know is that there is a lot of book work to sportscasting.”

Helfer’s wife during these years with Game of the Day, Ramona, claimed that her husband once had breakfast at their home in Hartsdale, N.Y., lunch in Boston, and dinner in Chicago.

“For two months after we moved to Hartsdale, neighbors thought I was a widow,” Ramona Helfer continued. “They saw my mother, baby and me. But never a man. My neighbors were right. I am a sports widow.

“Not long ago he finished a game in Chicago and had nothing to do for a few hours. So he caught a 6 p.m. plane for Cincinnati and got to the ballpark just in time to see the first pitch. What are you going to do with a guy like that?”

But Helfer’s Game of the Day travel did eventually take its toll and he resigned in January 1955. “It was a killing job. I seemed to be eating and sleeping in airplanes most of the time.”

“I’ve traveled too much in my life. I was known as the Ghost of Hartsdale,” he told the New York Post in 1957. “I was the only guy I ever knew who would come home, pick up fresh laundry, and get out the door before it could swing shut. The only time I spent with my wife was on the long distance telephone. My daughter was growing up and I didn’t know her.”

Helfer’s last big league broadcast partner was Monte Moore, the two sharing the booth for the Athletics’ first two seasons in Oakland in 1968 and ’69.

“When I was a senior in high school in Oklahoma, I came down with rheumatic fever so I was on bed rest for several months,” Moore said. “When I was in bed I would listen to the Mutual Game of the Day featuring Al Helfer. When I listened to him while I was in bed it encouraged me to do what he was doing. That was my first memory of Al Helfer.”

It was said at the time of Helfer’s death – he passed away in 1975 at the age of 63 – that he had traveled more than five million miles in his career.