- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Football careers for baseball fans

#Shortstops: Football careers for baseball fans

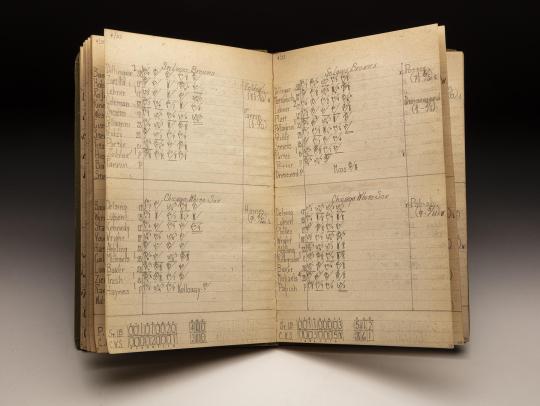

It’s a just a smallish notebook, about the size of a paperback book or an iPad. But its decades-old pages tell a unique story about baseball and football, fandom and friendship, memories and mourning.

Today, thanks to the generosity of its donor, it’s a part of forever at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

Upon its green canvas-bound cover, measuring 5 ¼ by 8 inches, is handwritten in block letters “Baseball 1948,” while inside there are approximately 100 lined pages. “Manufactured by U.S. Government Printing Office” in small type on the first page suggests it was to be used for recording information for the armed forces. But as any fan of the National Pastime who might thumb through its marked up pages would quickly realize, this was not used for military purposes.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Harry Hulmes served as a radar operator aboard ship in the Navy toward the end of World War II and a few years afterward. In his free time at sea he played a baseball dice game, keeping meticulous statistics and records in beautiful penmanship.

Inside the 1948 version of Hulmes’ “fantasy baseball” are a list of imagined American League and National League games, one per day, beginning April 13; first half and final standings in both leagues; two pages devoted to each of the 16 big league teams with lists of batters and pitchers; statistical league leaders; and box scores. In the margins are notes to himself, even one noting the amount of money he sent to his parents.

Also as part of the donation is a one-page typed copy of the dice game rules. These include, among a host of other baseball intricacies such as advancing on an out, sacrifice attempts, and stolen bases, the two-dice results for an at-bat: 1-1 is a two-base hit; 1-2 is a single; 1-3 is a groundout to third; 1-4 is a fly out to left field; 1-5 is a single; 1-6 is a groundout to shortstop; 2-2 is a two-base hit; 2-3 is a groundout into a double play (only when first base is occupied); 2-4 is a pop fly out to the infield; 2-5 is a strikeout swinging; 2-6 is a groundout to second base; 3-3 is a base on error; 3-4 is a fly out to right field; 3-5 is a strikeout called; 3-6 is a fly out to centerfield; 4-4 is a home run; 4-5 is a base on balls; 4-6 is a groundout to pitcher; 5-5 is a single; 5-6 is a groundout to first base; 6-6 is a three-base hit.

Hulmes’ younger brother, Jay, wrote in a letter that it’s ironic that Harry spent 50 years in the National Football League under the radar, yet makes it into baseball’s Hall of Fame based on a game he played in his radar shack while cruising the Pacific at 15 knots on an oil tanker (USS Sabine) during and after WWII.

“As for the dice game, he developed it way before his stint in the Navy. He graduated from Philly’s old Northeast High in 1945,” Jay Hulmes wrote. “We lived in a row house in the city’s West Oak Lane section, and in the summer during his high school years, I could hear games under way in his bedroom. He rolled the dice on the seat of a wooden chair while he sat on the edge of his bed.

“As you know, each baseball move/decision hinged on the roll of his dice. Harry not only rolled the dice, he narrated the game like a radio play-by-play announcer. He also provided the cheers of the crowd and the sound of bat hitting ball. He kept league standings and box scores. I think he used the Phillies and A’s lineups of the ‘40s. In July ’45 he entered the Navy and his game hit the road – or sea. I also played the game, but re-rolled if I didn’t like what the dice dictated – never told Harry.”

Fast forward seven decades and Ernie Accorsi, an acclaimed veteran of NFL front offices for more than three decades, approached the Hall of Fame about donating this treasured artifact that once belonged to his longtime friend, gridiron colleague and fellow baseball lover.

“When Harry passed away at the age of 88 in 2016, his wife called me and said she had so much stuff there that they were going to throw out,” remembered Accorsi in a recent telephone call. “I told her I didn’t want anything but the 1946 and 1948 logbooks Harry kept for his baseball game. So she sent me the two logbooks. I don’t think there’s any way that I can put into words that could describe Harry Hulmes better than those two log books.

“I would have had a hard time parting with the 1948 edition if it was the only one. But I have the one from 1946 right here on my desk. It’s like a piece of Harry. And it’s such a perfect piece of Harry. So just having that book, and to see that penmanship, how neat he was, it just brings Harry back to life for me.”

Hulmes, a native of Philadelphia, served as a radar operator in the U.S. Navy in the South Pacific and Persian Gulf for three years before attending college. A 1952 graduate of University of Pennsylvania with a degree in journalism, he joined the Baltimore Orioles as assistant business manager in 1954, moved to Bucknell University as the college’s Sports Information Director in 1956, then was hired by the Baltimore Colts in 1958 as business manager – beginning a half-century in the NFL – before becoming the football team’s publicity director in 1961.

The 39-year-old Hulmes was named Colts general manager in 1967, then, after a dozen seasons with the franchise, during which the team won two NFL titles, moved to the New Orleans Saints three years later. First serving as the team’s public relations director, he would in his 13 years with the Saints also hold such titles as assistant general manager, director of player personnel and vice president of administration.

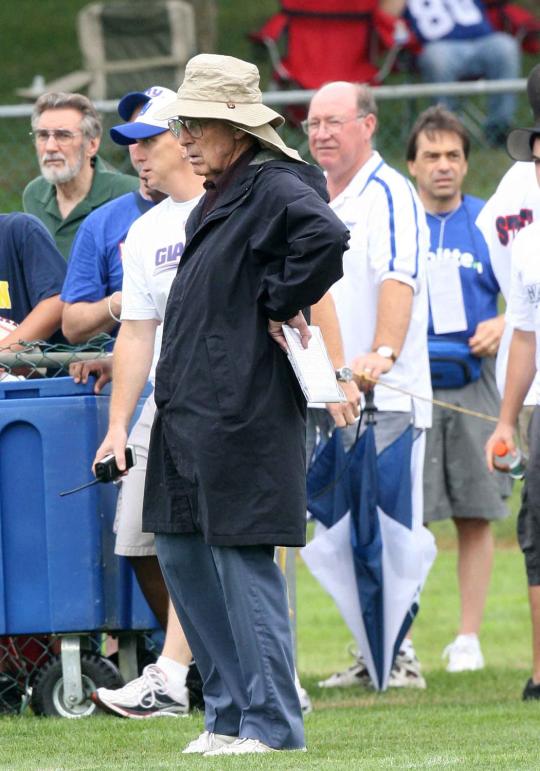

After a one-year stint with the USFL’s Arizona Wranglers, Hulmes joined the New York Giants as special assistant to the general manager in 1984. Later becoming a special assistant to the GM, he left that post in 1998, but remained with the team as a player personnel scout. Hulmes was a scout emeritus when he retired following the 2008 season having been a part of three Super Bowl winning teams with the Giants.

Accorsi first met Hulmes in 1963 when, while working as a sportswriter for the Charlotte News, he went to cover a Baltimore Colts game and Hulmes was the team’s public relations director. The pair became fast friends when Accorsi joined the Baltimore Evening Sun in 1964.

“I asked him one time, ‘Why did you volunteer for the all-night shift in the Navy all the time?’ He said, ‘Because I played my dice game.’ I said, ‘What are you talking about?’” Accorsi recalled. “So he brought me in this book. He played every game in the schedule. And he kept individual stats. So I looked at this book and said, ‘I don’t want anything from you, but you tell your wife Barbara, and I want it in writing, that I get this if you die before me.’”

The 79-year-old Accorsi, born and raised in Hershey, Pa., served as the general manager of the NFL’s New York Giants from 1998 until he retired after the 2006 season. The 1963 graduate of Wake Forest University had previously been GM for both the Baltimore Colts (1982-83) and Cleveland Browns (1985-92).

After college, Accorsi wrote to every baseball club but received no job offers. Eventually he landed a position in the sports department of the Charlotte News, where one of his first assignments was interviewing Archibald “Moonlight” Graham.

Graham, a former Charlotte minor leaguer in town for a reunion, would later be portrayed by Burt Lancaster in the beloved 1989 film Field of Dreams.

Accorsi would land his first NFL job in 1970 as the Colts’ public relations director. In 1994, after working in almost every phase of football operations, he took a job with the Baltimore Orioles as the team’s executive director of business affairs. A few months later he was back in football as assistant GM of the New York Giants.

“When I came to work under Giants general manager George Young, Harry was the assistant general manager. And I remember telling George, ‘I’m not coming here if you fire Harry Hulmes.’ So he kept Harry Hulmes,” Accorsi said. “And Harry stayed after I retired.

“When I took over from George Young as Giants general manager, Harry walks into the office and he sort of mumbled, he kind of talked into his tie knot. Finally I said, ‘Harry, what are you trying to say?’” Accorsi remembered. “Harry said, ‘You don’t have to keep me.’ I said, ‘Harry, let me tell you something. There is no way you’re going anywhere. Now get out of my office.’ But that was Harry.”

The two longtime friends and colleagues also shared a secret that they never talked about publicly.

“We spent our entire lives – and between the two of us probably 90 years in the NFL – with baseball being our true love,” said Accorsi, involved in the Hall of Fame’s membership program since 2005. “Harry was the quintessential Phillies fan. He was a fanatic. His father worked in a warehouse overlooking Baker Bowl on Lehigh Avenue and Broad Street and he couldn’t see the outfielders but he could see into the game. Harry would go with his dad and sit at the window and watch the games.

“One of Harry’s children is even named Richie after Richie Ashburn.”

As for Accorsi, he said, “I feel almost religiously connected to the sport through my dad,” echoing a common refrain involving fathers, sons and the game. “There is a reverence that I have for baseball where I just want to be part of anything having to do with it.”

Accorsi was hooked by the time he saw his first game in person, a 1950 doubleheader in Philadelphia in which Brooklyn’s Jackie Robinson stole home.

Hulmes’ widow, Barbara, added how meaningful the Hall of Fame donation experience has been for the entire family.

“If Harry only knew that in some little way he made the Baseball Hall of Fame,” she said. “He’ll never get into Canton on his merits, but if he knew that in some small way that his name would be in Cooperstown it would just mean the world to him.

“Harry would be so proud and happy that his logbook from so many years ago would be housed in the Baseball Hall of Fame. He loved baseball very much and followed it meticulously every day of his life, especially his beloved Phillies. This has made me and the children very happy and I know he’s smiling down on us.”

Accorsi aptly summed up the story of two football men who loved baseball and a special artifact now a part of the Baseball Hall of Fame permanent collection that represented their longtime friendship.

“Baseball is more of a way of life than football because it’s every day. It’s so long and you live it every day,” he said. “Plus, if you’re my age, baseball was the sport. We all grew up worshipping baseball.

“And Harry would just be blown away if he knew this.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum