- Home

- Our Stories

- In 1946, unfathomable tragedy struck the Spokane Indians

In 1946, unfathomable tragedy struck the Spokane Indians

It was one of the most tragic accidents in baseball, and it came less than a year after one of the most traumatic periods in American history.

On June 24, 1946, a bus carrying 15 members of the Western International League’s Spokane Indians tumbled off the highway crossing over Snoqualmie Pass. Nine team members died. The other six were severely injured.

For a nation recovering from the horrors of World War II – and enjoying the first peacetime baseball season in five years – it was an unfathomable catastrophe.

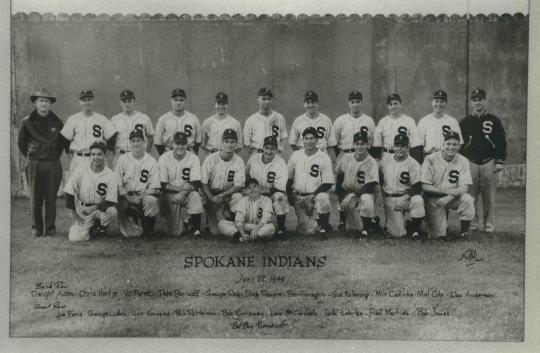

It was the first year the Western International League had resumed play following a three-year break due to World War II, and the Indians had promise. They had just wrapped up a homestand by splitting a doubleheader with the Salem Senators on June 23, closing it out with a dramatic 10-9 victory in the nightcap. Between games that day, the team photo was taken at Ferris Field.

With the win, Spokane moved to within 5½ games of first-place Salem. The Indians were in fifth place in the crowded WIL standings and set to face off with the fourth-place Bremerton Bluejackets next.

The following day, the team hit the road at 10 a.m., boarding a Washington Motor Coach bound for Bremerton, Wash. Absent from the bus were right-handed pitchers Milt Cadinha and Joe Faria, who had elected to drive separately with their wives.

Though the bus set out with 16 team members on board, by the time it crossed Snoqualmie Pass, that number was one fewer. On a stop for lunch, third baseman Jack Lohrke received a message that he had been recalled by the San Diego Padres of the Pacific Coast League. He hitched a ride back to Spokane, and the rest of the team proceeded on without him.

For Lohrke, it was another stroke of good fortune in a life that would earn him the nickname “Lucky”.

Around 8 p.m. that night, as the bus drove over Snoqualmie Pass on Highway 10, a black car approached from the other direction and crossed over the center line, headed straight for the bus. Driver Glen Berg swerved to avoid it, but the car sideswiped him anyway. The bus then swerved onto the shoulder of the road, crashed into and took out the barrier and plunged an estimated 300-500 feet down the side of the mountain.

“I saw the headlights coming toward us on the wrong side of the road,” outfielder Levi McCormack told the Associated Press shortly after the accident. “The road was slippery. Our driver applied his brakes. We swerved across the road into the guard rail. We went through. We went down. I’ve never heard such hell. I don’t know why we didn’t smash the other driver. It might have been better.”

When it hit the ground, the bus burst into flames. Some of the passengers were thrown out the windows or climbed through them to escape. Others never made it out.

“There was such a stillness,” outfielder Gus Hallbourg told the Spokesman Review in 1996. “I didn’t even hear yells or screams when we went over the side.”

Six team members died at the crash scene: second baseman Fred Martinez, outfielder Bob James, pitcher Bob Kinnaman, outfielder Robert Paterson, shortstop George Risk and player-manager Mel Cole. First baseman Vic Picetti died upon arrival at the hospital, while pitcher George Lyden died the following day and catcher Chris Hartje two days later.

“I said goodbye to everybody on the bus and hitched a ride back to Spokane,” Lohrke, who survived the Normandy Invasion and the Battle of the Bulge as an Army soldier during World War II and was bumped from a transport plane that eventually crashed in 1945, told the Spokesman-Review in 1986. “When I got back, I called the baseball office and told them, ‘I’m back.’ They said forget about that. There’s been a big bus crash and we think it’s our boys. I wasn’t sure about what happened, and then when I did find out, both of my roommates were killed.”

Team owner Sam Collins was in charge of the difficult task of notifying next of kin.

The survivors, in addition to Berg, included pitcher Pete Barisoff, second baseman Ben Geraghty, Hallbourg, catcher Irv Konopka, McCormack and pitcher Dick Powers.

“We rushed over to the hospital and saw all the players, the ones who were still alive, in the hallways because they didn’t have room for them,” Cadinha told the Spokesman-Review in 1986. “It was absolutely unreal. It just broke our hearts. I had just lost everything, all those friends.”

Even those who survived would never be the same again, and several would not return to the Indians that season.

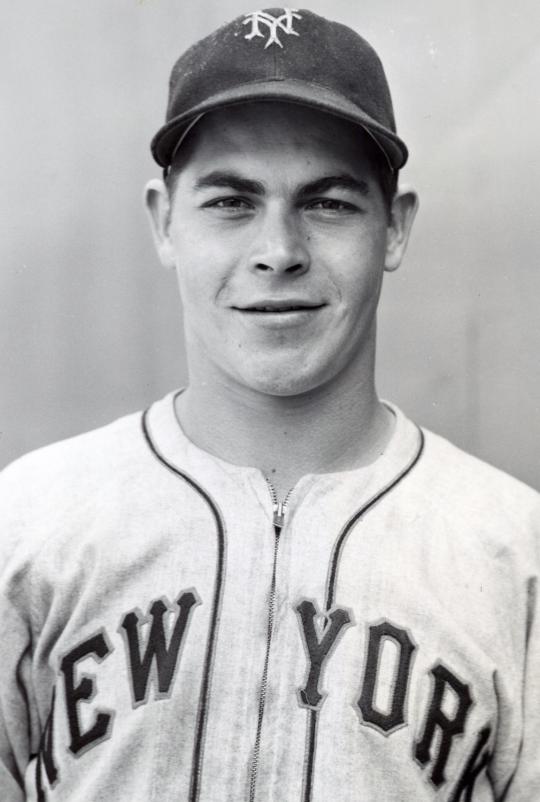

Lohrke would reach the major leagues in 1947, playing seven seasons with the New York Giants and Philadelphia Phillies.

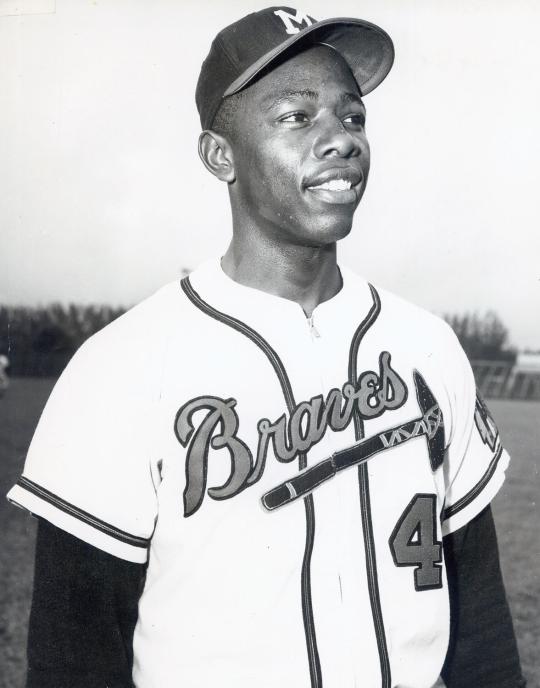

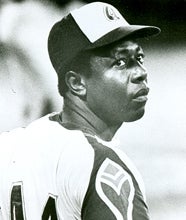

Geraghty ultimately took over as Spokane’s manager and went on to a successful career as a minor league manager. As the skipper of the South Atlantic League’s Jacksonville Braves in 1953, he managed a 19-year-old prospect named Hank Aaron. The future Hall of Famer often noted that Geraghty fought against prejudice Aaron encountered and was a huge influence on his career.

Geraghty became one of the most successful minor league managers of his time, helping stock the Braves teams that won two National League pennants and the 1957 World Series.

Following the accident, though it was clearly low on everyone’s priority list, there was still the matter of the rest of the 1946 season to be played. The situation was completely unprecedented, and it was unclear to everyone how the Indians would proceed.

“There is no league rule covering such a terrible situation,” Robert Abel, president of the Western International League, told the AP.

Spokane ultimately returned to play on July 4, with other teams lending players to help fill out their roster.

“Mr. Collins did the best he could to get a representative ballclub out there,” Hallbourg told the Spokesman-Review in 1993. “You’d look around and expect to see the guys out there, but we were all strangers.”

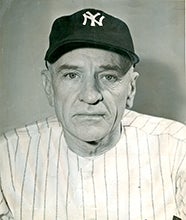

Banker Rex Raymond spearheaded a fund to raise money for the families of the players who had passed away, calling it the Spokane Baseball Benefit. Several benefit games were held to raise money, including one on July 8 at Spokane’s Ferris Field between the Oakland Oaks and the Seattle Rainiers of the PCL, in which future Hall of Famer Casey Stengel participated as Oakland’s manager.

Ultimately, the Spokane Baseball Benefit reportedly raised over $118,000 for the cause. And while nothing could bring the team back together again, what played out that season demonstrated the ability of competitors to come together and support one another in the face of unimaginable tragedy.

“I have one of the big team pictures in the back room and I see it every day,” Spokane team trainer Dutch Anderson told the Spokesman-Review in 1993. “I think about those guys, just getting started in life. They all had high hopes, and the bubble busted.”

Janey Murray was the digital content specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum