- Home

- Our Stories

- Gehrig’s pro career started four years before he became Yankees’ first baseman

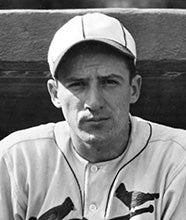

Gehrig’s pro career started four years before he became Yankees’ first baseman

One-hundred years ago, a new first baseman playing under an assumed name made his professional debut with the Eastern League’s Hartford Senators.

In 2021, that player will be honored with the inaugural “Lou Gehrig Day” to be held June 2 throughout Major League Baseball.

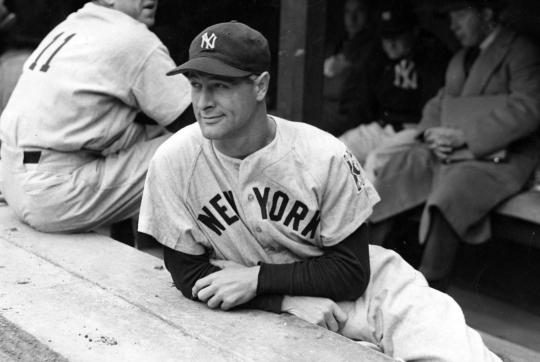

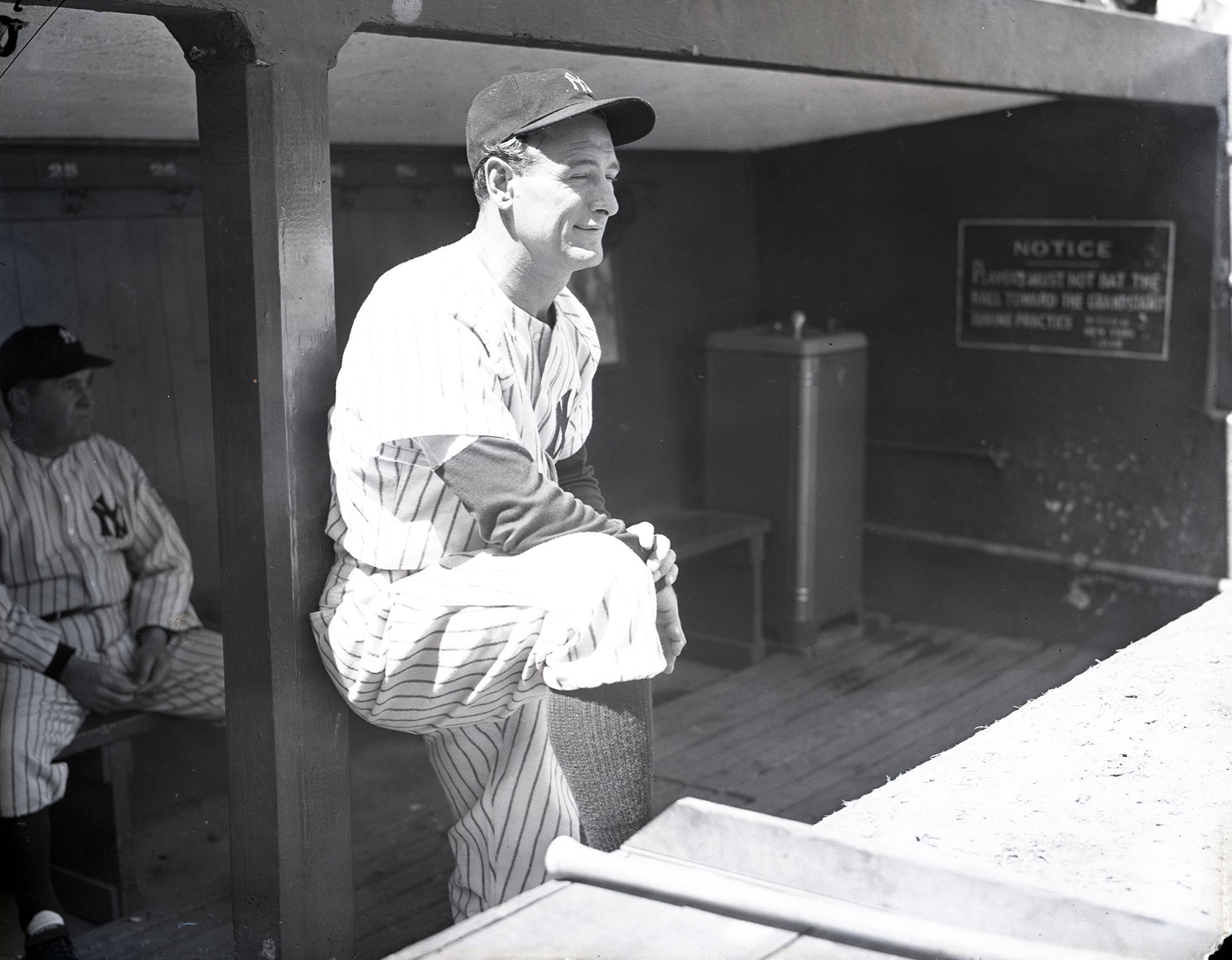

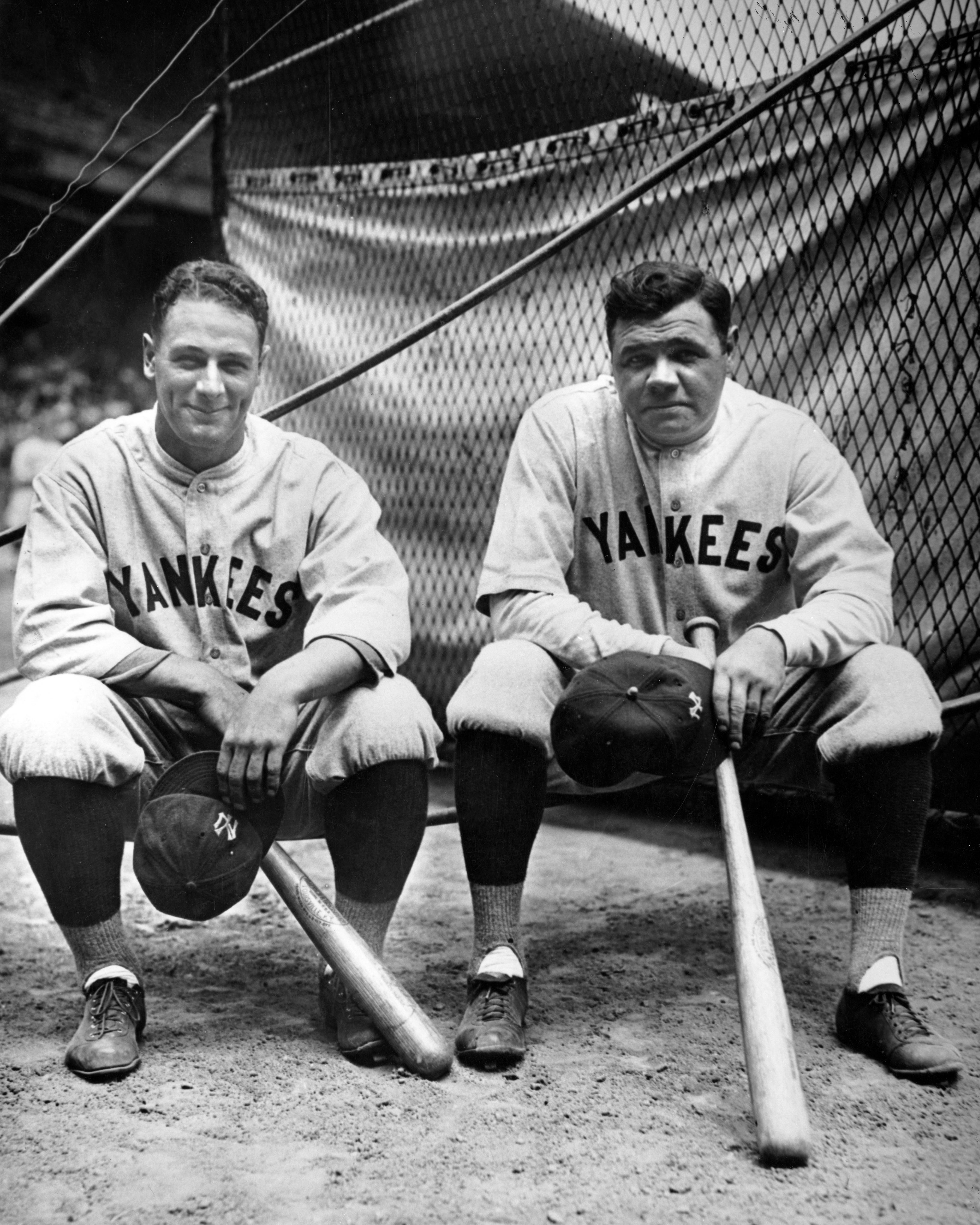

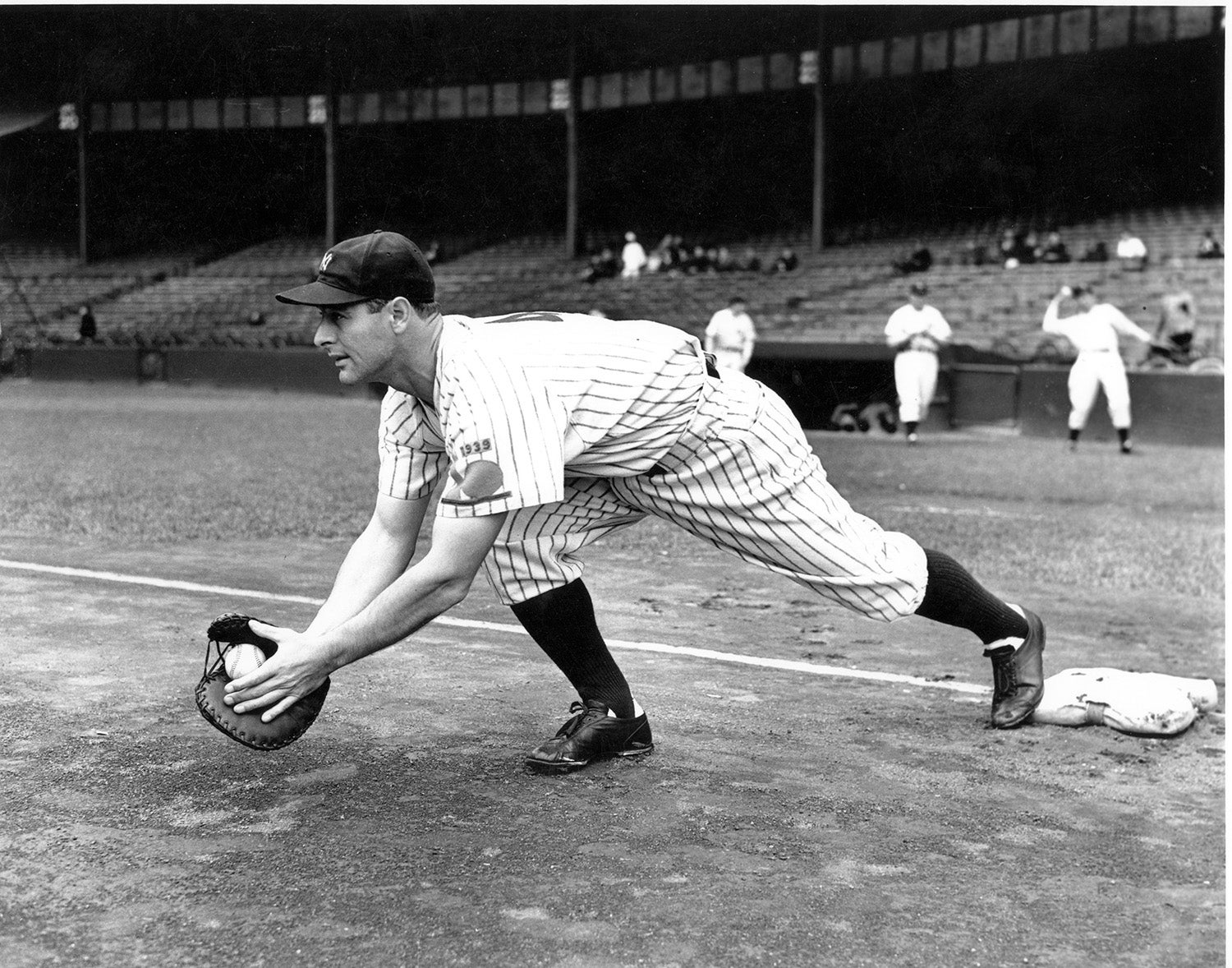

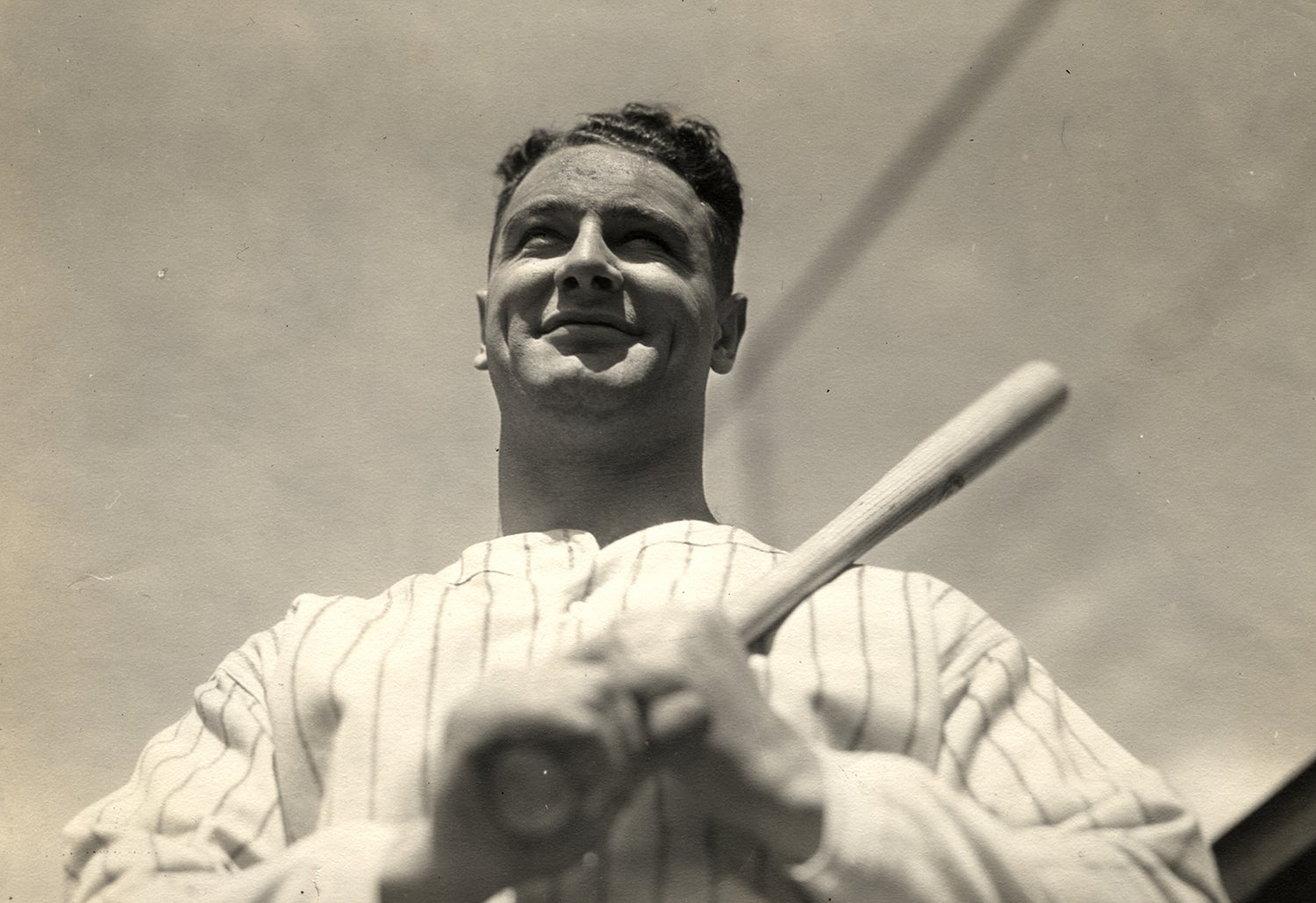

The name Lou Gehrig still conjures images of greatness, even though he played his last game in 1939. Teaming with Babe Ruth to form one of the game’s greatest offensive twosomes, Gehrig spent his entire 17-year career as a first baseman with the New York Yankees, helping the team to seven World Series titles.

Yankees Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

During his illustrious career, the “Iron Horse” had 13 consecutive seasons with more than 100 runs batted in and 100 runs scored, knocked in an American League record 185 runs in 1931, won the Triple Crown in 1934 and played in 2,130 consecutive games, a record that would stand until 1995 when Cal Ripken Jr. passed it.

According to MLB, June 2 was chosen as the date for Lou Gehrig Day as it’s when Gehrig became the Yankees starting first baseman in 1925 as well as the day he passed in 1941 from complications of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease.

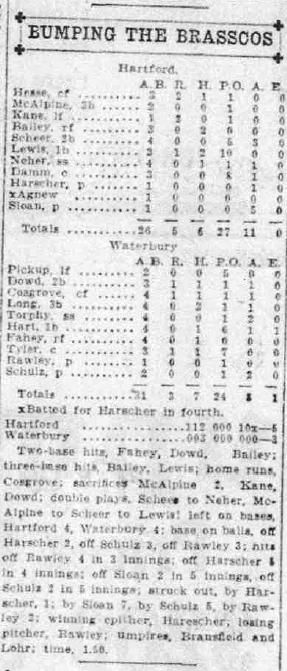

But it was back on June 3, 1921, that the 17-year-old, playing under the name “Lou Lewis,” helped Hartford defeat Pittsfield. The young first baseman batted 0-for-3 with a sacrifice, an inauspicious start for the Class of 1939 Hall of Famer. After all, Gehrig had only graduated from New York City’s High School of Commerce in January 1921, then enrolled at Columbia University on a football scholarship a month later.

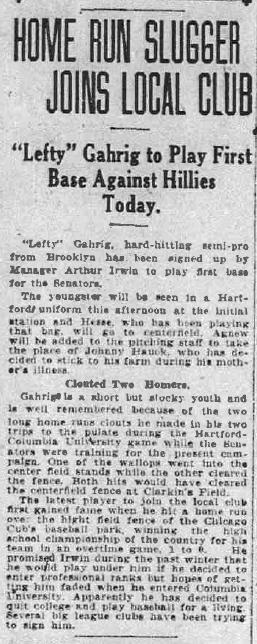

In the June 3, 1921 edition of The Hartford Courant, it was reported, with a misspelled surname, that “’Lefty’ Gahrig, hard-hitting semipro from Brooklyn, has been signed by Manager Arthur Irwin to play first base for the Senators.

“Gahrig is a short but stocky youth and is well remembered because of the two long home runs clouts he made in his two trips to the plate during the Hartford-Columbia University game while the Senators were training for the present campaign. One of the wallops went into the center field stands while the other cleared the centerfield fence at Clarkin Field.

“He promised Irwin during the past winter that he would play under him if he decided to enter the professional ranks but hopes of getting him faded when he entered Columbia University. Apparently he has decided to quit college and play baseball for a living. Several big league clubs have been trying to sign him.”

Soon, though, “Lefty” Gahrig was being referred to as “Lewis.” In the June 5, 1921, edition of The Hartford Courant, the game story read, “In the second inning … Lewis, Hartford’s youthful first sacker, hit the first ball pitched for three bases to right field.”

Gehrig would go on to play a dozen games for Hartford as “Lewis,” batting .261 (12-for-46) with zero home runs, a double and two triples.

Reportedly, when word reached Columbia University’s baseball coach, the former big league pitcher Andy Coakley, he told Gehrig he was jeopardizing his collegiate athletic eligibility and to return to school. Coakley, meanwhile, convinced rival schools that Gehrig should only be suspended for one year from the Columbia baseball team as a penalty for playing pro ball with Hartford.

Ray Robinson, in his book, “Iron Horse: Lou Gehrig in his Time,” wrote, “Gehrig always insisted that he had no idea he would be barred from Columbia’s teams if he accepted the play-for-pay offer.”

Gehrig, who rarely discussed his turn as “Lewis” in 1921, addressed the controversy in the April 22, 1937 issue of the Sporting News.

“As a freshman in Columbia I played a little league ball during the summer vacation. John McGraw had me at the Polo Grounds but did not give me too much attention nor did he seem to be impressed with my possibilities. I have often thought because of later developments if he had given me a real opportunity to make good and taken pains with me the baseball situation in New York perhaps would have been a lot different in the years that were to come.

“McGraw sent me to Hartford in the Eastern League, which was managed by Arthur Irwin. I played under the name of Lewis. I was sore over the lack of attention from the Polo Grounds and sore over the situation in Hartford.”

Gehrig went into more detail in an April 1938 column in the New York World-Telegram by Joe Williams.

“Here’s how it was,” Gehrig told Williams. “I was going to Columbia. A fellow came up and asked me how I’d like to work out with the Giants. He was a semipro umpire. I’ve forgotten his name and that distresses me. The fellow played an important part in my life. I’d like, at least, to give him credit for starting me out when people ask me that question. I feel like a dope that I can’t remember his name.

“Anyway, I went over to the Polo Grounds and reported to Cozy Dolan, as per instructions. Dolan was one of the Giants’ coaches. I worked out with some other youngsters in the morning. Maybe for a week or so. One day Dolan told me to hang around. ‘I want John McGraw to take a look at you,’ he explained. McGraw, of course, was managing the Giants. I did my stuff before the old maestro. He asked me if I was interested in going to Hartford for the season. I explained I didn’t want to jeopardize my college standing. I still had two more years at Columbia.

“’I’ll take care of all that,’ he said. ‘Your name’s Lewis. Lou Lewis. You report to Arthur Irwin at Hartford and tell him to play you at first base.’ There isn’t much more to the story. I was pretty awful around first. Green as grass. And I wasn’t knocking down any fences with my hitting either. Besides, I didn’t like the life of a professional at the time. Not in that league, anyway. I was homesick.”

Over the years, other Hall of Famers, in order to protect their amateur status, also began their professional baseball careers playing under an assumed name, including Joe Medwick, who was Mickey King with the Scottdale (Pa.) Scotties of the Middle Atlantic League in 1930, and Mickey Cochrane, who was Frank King with the Dover (Del.) Senators of the Eastern Shore League in 1923.

Gehrig would return to Hartford two years later after signing with the Yankees in 1923. In 59 games with the Senators, he batted .304 with 24 homers, a clear improvement from 1921. Even the Hartford newspapers recognized the difference in name and performance, referring to him as “Lefty Lou” Gehrig, champion fence-buster of the Eastern League.”

Going forward, on June 2, Gehrig will now join fellow Hall of Famers Jackie Robinson (April 15) and Roberto Clemente (Sept. 9) as players whose legacies are celebrated annually with dedicated, league-wide days.

The focus of Lou Gehrig Day will be: Remembering the legacy of Gehrig and all those lost to the disease that bears his name; raising awareness and funds for research of ALS; and celebrating the groups and individuals who have led the pursuit for cures.

“Major League Baseball is thrilled to celebrate the legacy of Lou Gehrig, whose humility and courage continue to inspire our society,” said MLB Commissioner Robert D. Manfred Jr. “While ALS has been closely identified with our game since Lou’s legendary career, the pressing need to find cures remains.

“We look forward to honoring all the individuals and families, in baseball and beyond, who have been affected by ALS and hope Lou Gehrig Day advances efforts to end this disease.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum