- Home

- Our Stories

- Baseball’s Sad Lexicon immortalized a historic infield

Baseball’s Sad Lexicon immortalized a historic infield

The story goes that one afternoon in July 1910, New York Evening Mail columnist Franklin P. Adams was itching to get out of the office and attend the New York Giants game at the Polo Grounds.

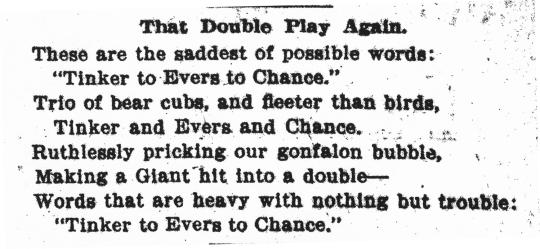

But the foreman of the composing room said: “Wait – I need eight more lines before you can go.” So FPA, as he was known, sat down and wrote these eight immortal lines, entitled “Baseball’s Sad Lexicon:”

These are the saddest of possible words:

“Tinker to Evers to Chance.”

Trio of bear Cubs and fleeter than birds,

Tinker and Evers and Chance.

Thoughtlessly pricking our gonfalon bubble,

Words that are heavy with nothing but trouble:

“Tinker to Evers to Chance.”

As he hurried to the ball game, FPA probably wasn’t thinking that he had just achieved baseball immortality, and that more than a century later readers would still enjoy his hastily-composed poem.

The poem is the second best-known work of verse ever written about baseball – right behind “Casey at the Bat.” Interestingly, both poems tell of failure for the home team, in this case the turning of a double play by the Cubs against the Giants. The next day, editor T.E. Niles told FPA that “no matter what else I ever wrote, I would be known as the guy that wrote those eight lines,” Adams remembered in a 1946 letter to Ernest Lanigan of the Baseball Hall of Fame staff.

It is often assumed that since the poem is about the great rivalry between the Giants and the Cubs that FPA was hurrying out to a game against the visiting Cubs. But the Giants didn’t host the Cubs at all in July of 1910. Instead, they visited Chicago July 9-11, taking two out of three from the first-place Cubs. In fact, had the Cubs not salvaged the final game of the series, the Giants would have moved into first place.

The poem first appears under its title, “Baseball’s Sad Lexicon,” in the Evening Mail on July 18, 1910. But the history of the eight-line masterpiece is much more complicated.

The Evening Mail for July 18, 1910, features three more eight-line poems that were clearly responses to “Baseball’s Sad Lexicon” cited as previously appearing in the Chicago Tribune. This meant that the poem had to have appeared somewhere prior to July 18.

Working backwards in the Chicago Tribune and the Evening Mail, it emerged that the poem had appeared twice under different titles: On July 12 in the Evening Mail, under the title “That Double Play Again,” and on July 15 in the Tribune, with the title “Gotham’s Woe.”

The three other poems reprinted on July 18 had all appeared in one paper or the other between the 12th and the 18th. Newspapers in both New York and Chicago were carrying on a conversation about the Cubs-Giants rivalry, touched off by FPA’s immortal baseball poem.

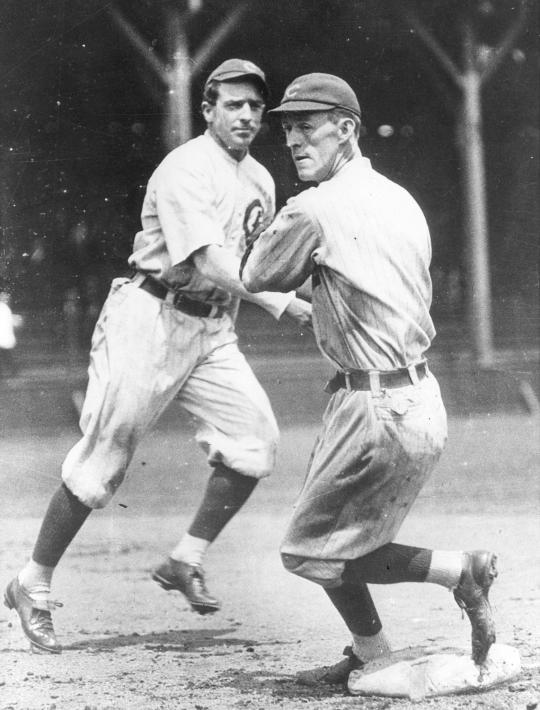

Most exciting, to a fan of both baseball and poetry, was that the July 11 series finale, won by the Cubs, had featured a Tinker to Evers to Chance double play. It was now possible to isolate one of the double plays turned by the fabulous infield as the inspiration for “Baseball’s Sad Lexicon.”

The excitement didn’t end on July 18, but rather continued on for years, with FPA trading witty poems with the Tribune’s writers over the Cubs and Giants, and even expanding the conversation to include the Pirates, Dodgers, Yankees and the Athletics. There are at least 30 poems that have been discovered – all based on Adams’ gem.

One of the best of these poems was written by “DEL” in the Chicago Tribune on July 20, 1910:

In Baseball’s Lexicon

While you’re about it, don’t overlook these:

Overall, Reulbach and Brown.

Opposing batters oft hit but the breeze—

Overall, Reulbach and Brown.

Flies to the outfield? They’re nabbed in the air!

Sheckard and Hofman and Schulte are there.

Bunts? Steiny grabs ‘em. All honors they share—

Overall, Reulbach, and Brown.

This poem of course celebrates the Cubs’ pitching and fine defense and marks the first appearance in verse for Harry Steinfeldt, the Cubs’ capable third baseman, who has been relegated to footnote status because of the celebrated and melodious infielders with whom he worked.

On Aug. 4, 1910, FPA revisited the double play combination, after yet another Cub victory:

What was it busted up yesterday’s game?

“Tinker to Evers to Chance”

Whom do the Giants consistently blame?

Tinker and Evers and Chance.

Terrible three of a terrible crew,

Diamond demons, we give you your due,

Beating us, still we must hand it to you,

Tinker and Evers and Chance!

On Oct. 21, 1910, the Tribune’s ‘DEL” added this postscript. Just as the season was ending and the Cubs were about to take on the A’s in the World Series, Johnny Evers broke his ankle during a six-game series against the Cardinals:

These are the saddest of possible words

“Evers is out of the game.”

Though the Cubs have subs to throw at the birds,

Evers is out of the game.

Deep in the hearts of Cub fans woe doth rankle;

Bender and Coombs have both won, and now Plank’ll

Turn the same trick—why did John break his ankle!—

“Evers is out of the game!”

Many have speculated whether Adams rooted for the Cubs (of his native Chicago), the Giants, of his adopted hometown – he was once described as “the quintessence of Manhattan,” by no less a pundit than Carl Van Doren – or even for both teams. His biographer, Sally Ashley, says that he was a fan of the Cubs, and “to a lesser extent, the Giants.”

Ashley also says that “Baseball was a passion for Frank,” and that “During the summers he journeyed to the Polo Grounds with his friends Grantland Rice, Damon Runyon, and, when he was in town, Ring Lardner. Often he bet gleefully against the Giants.”

In his letter to Lanigan, FPA settles the debate: “I was the only Cub rooter in the Polo Grounds press box,” and “I remember covering the 1912 Series, because it went to eight games, one a tie. I was always an anti-Giant boy, and I was joyful at the Red Sox and Athletics victories, to say nothing of the Cubs of 1906, 1907, 1908, and…1910.”

FPA was not primarily a baseball writer, but rather a general columnist whose beat included current affairs, language, and the literary and theatrical worlds. His career began in his native Chicago with the Journal, but he quickly left for New York and a regular column with the Evening Mail, beginning in 1904. In 1913 he switched to the New York Tribune, and later wrote for the World, the World-Telegram, the Herald Tribune and the Post.

From 1938 to 1948, he became a quick-witted personality on the “Information Please” radio show, some of whose episodes were so entertaining that they became movie “shorts,” played before and between the longer feature films in theaters.

His column, “The Conning Tower,” was the toast of New York literary society, no matter in which paper it appeared. One of his specialties was publishing new work and witticisms by up-and-coming young writers, and he played a major role in shaping American literary culture of the 20th century, helping to bring to prominence an amazing number of young writers, including Theodore Dreiser, Edna Ferber, George S. Kauffman, D.H. Lawrence, Sinclair Lewis, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Eugene O’Neill, Dorothy Parker, James Thurber, Edith Wharton and E.B. White.

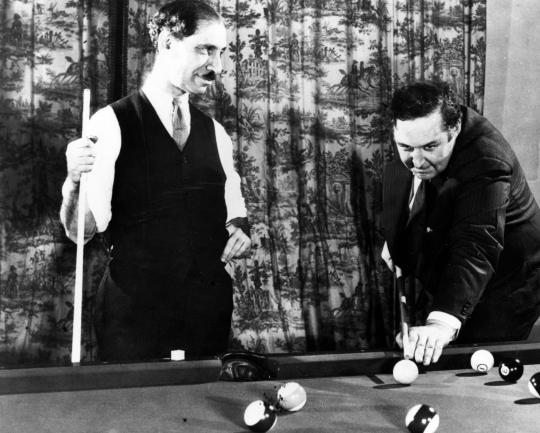

He was a founding member of the Algonquin Round Table, a group of writers, poets, and personalities who met daily for lunch at a special table at the Algonquin Hotel. He was portrayed by actor Chip Zein in the 1994 movie about the Algonquins, “Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle.” In addition to his long-running column, he wrote nearly 30 books and several plays and musicals.

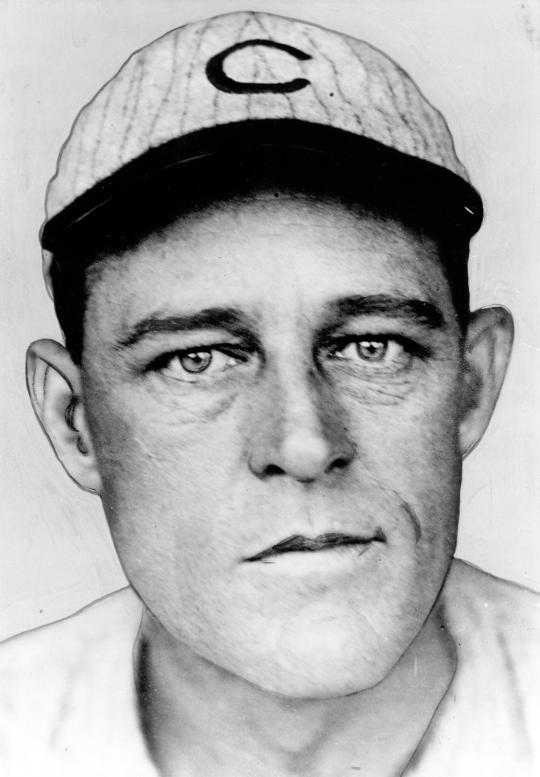

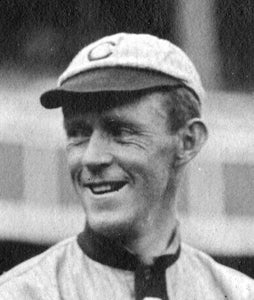

The Cubs, of course, were a true dynasty during the heyday of Tinker, Evers, and Chance, winning four pennants and two World Series in five years. During those five years, the Cubs averaged 106 wins and 47 losses per season, a sustained run of success that would not have been possible in the dead ball era without strong defense.

That infield defense was as scintillating as the poem that FPA composed that summer afternoon. The poem has perpetuated the names of all three players, and has given, as FPA biographer Sally Ashley wrote, “a phrase to the language.” Indeed, the phrase “Tinker to Evers to Chance” has been used even in non-baseball circles as synonymous with what historian Glenn Stout calls “a metaphor denoting cool efficiency.” It is something of a synonym for “like clockwork.”

Tinker, Evers, and Chance clearly were sublime. But without FPA’s sublime poem, their history would have been quite different.

Tim Wiles was Director of Research at the Hall of Fame. He gratefully acknowledges Jack Bales of the University of Mary Washington, Martin Gallas of Illinois College, and Joanne Hulbert of Mudville for research assistance.